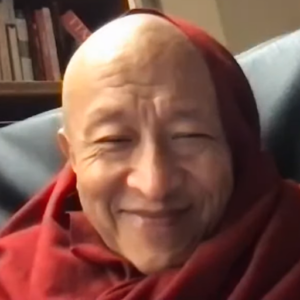

Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche

Sadhana of the Recollection of the Noble Three Jewels

Online from Taiwan

February 19, 2021

60 minutes

Transcript / Video (complete video is 137 minutes long and includes recitation of the sadhana)

Tri Ratna Anusmriti Sadhana website (includes sadhana text)

Note 1: This is an edited transcript of a live teaching, and should not be taken as Rinpoche’s final word. Every effort has been made to ensure that this transcript is accurate both in terms of words and meaning, however all errors and misunderstandings are the responsibility of the editors of madhyamaka.com. Please see note.

Note 2: This transcript includes footnotes with clarifications and more information about Tibetan and Sanskrit Buddhist terms used in the teaching. Please click on the superscript number to read the footnote. Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche’s name is abbreviated to “DJKR” throughout.

Sadhana of the Recollection of the Noble Three Jewels

Welcome

It’s so nice to see all of you. I really can’t get used to looking at my laptop and talking to people. It just doesn’t seem to work for me. Hopefully this is not always going to be like this now that the Russian Sputnik vaccine is out. I’m very [much] looking forward to this Sputnik. If anyone knows how to make chemicals, the [Russians] would be the best. Anyway, I’m not going to go too far there, otherwise I’ll be fried alive.

I’m just going through all the [images on the Zoom] gallery to look at all [your] living rooms and kitchens and what kind of taste [you have in] curtains and so forth.

Recollection and awareness

I’ve been asked to give some sort of introduction or summary of this Sadhana of the Recollection of the Noble Three Jewels [the Triratna Anusmriti Sadhana]1The sadhana text is available at the Tri Ratna Anusmriti Sadhana website..

The sutra itself, the Sutra of the Recollection of the Noble Three Jewels, comes from the Mahayana. However the term “sadhana” is actually a tantric term. It has a lot of tantric flavour. Let’s put it this way: you can translate sadhana as “a technique to accomplish”. So what are we trying to accomplish here? In the most broad sense, we are trying to accomplish the Sanskrit word smriti, I think that’s like “recollection”. But you know, recollection is – how should I put it? – it’s like a watered-down term. Because I think people like the word “recollection” much better than “awareness”. Awareness is very big, very abstract. And it’s so colourless, so to speak. But recollection [means] recollecting people in the past. Whenever we are talking about recollection, we are talking about something in the past.

This sadhana is actually a so-called mindfulness practice. You know, there are so many mindfulness things going on [these days]. This [sadhana] is just mindfulness practice. But even the word “mindfulness” has become diluted. It has become like the Indian word “chai”. Chai used to have such a beautiful connotation. It [used to] have that connotation or flavour of train stations, clay cups, sugar and thick hot Indian tea. Nowadays, there are so many [kinds of] chai, like soy chai. I just had one. Can you believe that? Soy chai. 40 years ago when we were traveling in India by train, you would hear the noise [of] people running around, chaiwallahs shouting “Chai, chai, chai, chai”. Like that. Now Starbucks has chai.

Awareness of Buddha, Dharma and Sangha

The word “mindfulness” has become [like] that. It has become so diluted. Probably the word “awareness” is slightly better. So in the Triratna Anusmriti Sadhana, when we talk about the recollection of the Noble Three Jewels, fundamentally what’s happening is awareness of the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Actually, it’s really as simple as that.

[For example], I’m looking at a swimming pool at the moment, even though it’s dark. And I know, I’m aware, that the pool is wet. And I don’t want to go in there right now. We are talking about that level of awareness. Buddha, Dharma and Sangha – these three are not outside. Let’s just put it this way first.

Dharma

Let’s begin with Dharma. Dharma is the truth. The truth of the matter is that even though Karma Jinpa is thinking at the moment, and he thinks that he’s alive, the truth of the matter is that he’s dying. So he should really work hard on his harvest. He has a harvest which I don’t want to tell you anything [about] right now, but he has a harvest. I’m not stopping his harvest, his cultivation. It’s a really lucrative cash crop. I’m not stopping that. What we are talking about here is [that] he must really remember or recollect or actually be aware that he is dying all the time.

There are many other facts, so many other facts [to be aware of]. For example, at the moment I’m sitting on a massage chair. In many ways it’s good, because you’re not obliged to [anyone]. But you know it’s very strange, because how long do you want your [calves] to be squeezed? [This massage chair] squeezes them. How long do you want them to be squeezed? [DJKR holds up the remote control for the massage chair]. I mean, how long? Twenty four hours? Seven days a week?

What I’m talking about is [that] no matter what we have, it’s never really going to satisfy us. There’s always a dissatisfaction. It’s almost like a massage is only good because it stops. It’s sort of inevitable [that] it has to stop. That’s why it’s good, so to speak. You understand? So behind all our satisfaction, there’s always a dissatisfaction. There’s a fundamental dissatisfaction. These are the truths that we have to be aware of.

The thing is, if you are aware of these truths, what it does is it makes you smart. Basically, that’s what happens. You become smart. You become cool. You become savvy. You become shrewd [in] dealing with your life. You become what the English call a “smart cookie”. You are always one step ahead. You’re not a fool, basically. You’re not a fool. That is what is basically [meant by] the recollection of the Dharma. It’s not like remembering some books.

Buddha

When we talk about the recollection of the Buddha, of course we recollect the guy who came 2500 years ago. And you can recollect [the Buddha] in many different ways, however you want. There are a bunch of Mahayana [Buddhists] who think that he was like some sort of amazing display of the wisdom body. And I’m sure there are a lot of Theravada-oriented [Buddhists] who think that he was a normal human being, which is so sweet. It’s so great. You know, he coughed. He got really frustrated when there was all this mischief played by his cousin Devadatta. And I’m sure [the Buddha] got a little bit uneasy when he was meeting King Ajatashastru, who later became one of his disciples. I think King Ajatashastru killed his own father [King Bimbisara]. He was a very vicious king.

We recollect the Buddha in many ways. Those descendants of Alexander the Great recollected him with curly hair, beautiful, [as depicted in] all those Gandhara statues. Almost all Buddhists seem to agree that he had curly hair.

The Chinese seem to want to recollect him as sort of chubby, almost on the fat side. And they have their reasons. During those days, the Chinese must have thought being chubby was very majestic, very wholesome, very cuddly. I don’t know, whatever. They must have [their reasons]. Which is fine, which is great. Now the Chinese are reading too much of American Vogue magazine. They all like anorexic types. I’m sorry, that was too sarcastic. I’m in a strange mood today, by the way.

Another common thing that we all seem to like to recollect [about] the Buddha is [that he had a] very big chest. I mean broad shoulders. I don’t know, I think he must have had that. By the way, he had blue eyes. I don’t know whether the Tibetans and Chinese and Koreans and Japanese can chew this. I think he was Caucasian. You know, Aryan. [He had] blue eyes. Beautiful blue eyes.

Anyway, when we talk about recollecting the Buddha, it seems that we like to talk about recollecting a historical Buddha, which is great. We are going to do this sadhana under the Bodhi tree very soon. You should all come. Karma Jinpa will bring his harvest at that time. I think he will make biscuits out of it.

But are we just recollecting some historical guy? No, not just that. Actually, more importantly, we are recollecting the innate Buddha, the Buddha within ourselves. Of course, it’s sort of unbelievable. It almost sounds poetic [to say that] we all have the Buddha nature. It sounds like a pep talk, some sort of encouragement talk. But actually it’s not really a pep talk.

Actually, [it’s] just like the impermanence and the dukkha [unsatisfactoriness] that I was talking about. We are really talking [about] the raw simple truth. Of course, you are packed with defilements and emotions and very thick murky cloudy stuff. I’m sure. But the fact of the matter is that all your emotions, they skid. Just like how you skid on a muddy surface, they all skid. Of course, sometimes it feels like they skid with the greatest slow motion, so you feel like [they are] there all the time. But, you know, they come and go. I mean, you are not angry, like fixed angry, for 24 hours. You’re not angry for more than even a few moments actually. If you are, then you are not a human being. You are a machine or you are some sort of inanimate thing.

Basically, no matter what kind of emotions and defilements you have, they are all temporary. And really, this is probably the best thing that you can observe and then really develop a conviction that your true nature is the Buddha. And the purpose of this sadhana is remembering, recollecting, and being aware of that.

Sangha

Remembering the Sangha can mean a lot of things. It can mean recollecting the disciples of the [Buddha], those who followed the Buddha like Shariputra, Ananda, Subhuti, all of those guys. [And also the Sangha of bodhisattvas such as] Mañjushri and Avalokiteshvara.

We human beings have this habit of looking up to these guys. For instance, if you like boxing, then just everything to do with Muhammad Ali will excite you. Wow! Even the way he enters the boxing ring will just excite you. What do you think? Can you imagine Karma Jinpa getting [a pair] of those boxing shorts? I think they have big letters “Everlast” or something like that. Just imagine that.

We like to look up to these guys. And [people have] a lot of different strange paradoxical feelings about these things. [For example], a lot of Chinese really love Bodhidharma, that Tamil guy who first went to introduce Chan Buddhism [in China]. I don’t know how many of them really want to look like him though. But they get so excited. They paint [pictures of] Bodhidharma [with] his bulging eyes and all of that. It is just something that we look up to.

And then on a more sort of practical level, there is the Sangha [of] the monks, the nuns, and the lay practitioners. Just to give you a general idea, in the Sutra of the Recollection of the Noble Three Jewels – I’m not taking about the sadhana, but the actual sutra – you will read things like “They enter insightfully, they enter straightforwardly, they enter harmoniously”. [This is] describing the idea of Sangha.

[All of] these things that I’ve just told you, each and every one of them has a lot of deep, vast meaning, I have to say. For instance, they enter straightforwardly. There is the truth [of] impermanence. And there is the truth of the innate Buddha nature.

When we are talking about Sangha, I think the most simple way to understand this is [in terms of] the path. We are talking about the simple awareness of the Sangha. Let’s go back to that one.

Defilements are defeatable. They are purifiable. And the Buddha, the innate Buddha, is discoverable. It is there. I always go back to my one example that I use again and again. Even though there is a [process] of washing [the] dishes, in reality the dirt that is being washed and the cup are two different things. [And] because they are two different things, this act of washing gives you the result of cleaning. Because if they were one, then the whole system, the act [or] the game of purifying, accumulation, and all of that doesn’t work.

Okay, so that’s what is to be remembered, recollected, and to be aware [of]. Anyway, this sutra is kind of quite a big sutra.

How to practice the sadhana

Now coming back to sadhana. Loosely translating, “sadhana” means something like “accomplishing”. Accomplishing the truth, accomplishing the Buddha within, through the system [of practices] such as cleaning, acquiring, aspiration, all of that.

Now, sadhana practitioners are people like you and me. In other words, people who have all kinds of values. All kinds of culture. All kinds of references. All kinds of habits and customs. All kinds of ways of relating to the world and to yourself. Because we have these kinds of habits, in the sadhana we use these habits as a vehicle. And then of course, our end aim is to shrug off and discard all those references, values and so forth. But in the practice, we use them. I will explain.

Right after the “Taking Refuge” (p. 14 in text of sadhana) and “Bodhichitta” (p. 15), there is (a section) called “Visualization of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas” (p. 16). You know, we human beings like to think of our saviour, [we like to have] people who we look up to. We like to think of them. So here we are basically borrowing that habit.

And in our head we think [things] like the lotus is a good thing. It’s a beautiful thing. So this is why we want the Buddha sitting upon a lotus (p. 16). And we have the dualistic mind of thinking that our teacher or guide or saviour should be majestic, compassionate, and alive. [So] we use all of that (p. 16). We’re using our own way of thinking to accomplish the innate Buddha. Basically, that’s what I’m saying here.

And then we think that all his disciples are there. We use ideas such as invitation. Basically we ask them to come (p. 17). I’ve already explained to you [that] there are two ways to understand this. You can visualize the buddhas and bodhisattvas actually coming from somewhere, or you can also bank on the idea that the Buddha is within. It’s not like he or they come from somewhere and [then] dwell [within you].

Then, of course, we ask them to sit (p. 17). Then we have [various] offerings. And then praise, which is something that we human beings do a lot. As human beings, what do we do? We give gifts [and] we praise [people], right? We are using the human habits here. And we have a lot of this [recitation of praise] in many different forms, and then we also offer what we call the Seven Branch Prayer (p. 24).

And now, actually the most essential practice or the most essential part of the sadhana is taking the Bodhisattva Vow (p. 29), [which is] basically planting the seed of the Buddhahood within oneself.

And once you have done that, then to sort of enhance our practice, we also have the recitation of the mantra of Shakyamuni (p. 33). And this is probably very sort of Vajrayana-oriented, so to speak, because, for instance, in the Theravada tradition, I don’t think they do the so-called chanting the mantra of Shakyamuni.

And basically, the foundation of doing the recitation of the mantra of Shakyamuni is really remembering, recollecting or being aware of the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha – the historical and external, or the truth, the internal. And then of course, towards the end, [there is] the dedication (p. 49).

So this is basically a very brief kind of introduction or summary of the sadhana that has been presented to you. And I heard that there are a lot of people who want to participate in this, which is fantastic. And please, even if you can’t do it every day, maybe try to come to the festival on this specific sadhana under the Bodhi tree. And beyond that I have nothing much to say.

Note: to read footnotes please click on superscript numbers.

Transcribed and edited by Alex Li Trisoglio