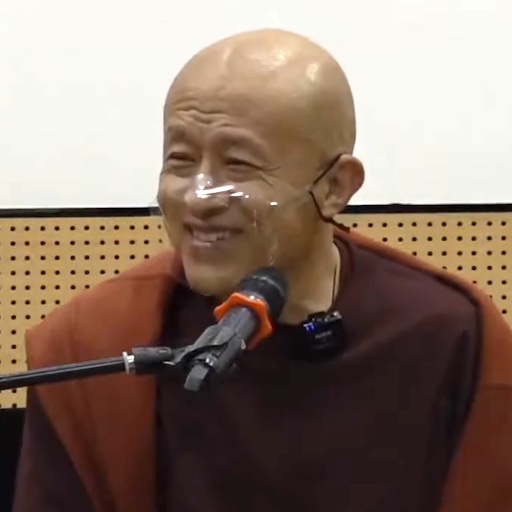

Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche

Dhyana

Note 1: This is an edited transcript of a live teaching, and should not be taken as Rinpoche’s final word. Every effort has been made to ensure that this transcript is accurate both in terms of words and meaning, however all errors and misunderstandings are the responsibility of the editors of madhyamaka.com. Please see note.

Note 2: This transcript includes footnotes with clarifications and more information about Tibetan and Sanskrit Buddhist terms used in the teaching. Please click on the superscript number to read the footnote. Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche’s name is abbreviated to “DJKR” throughout.

Part 1

(a) The purpose of dhyana

Introduction

Thank you so much for the very generous and slightly exaggerated introduction. I’m very honoured to be here in this Learning Center. I was told that the audience is very mixed, from very beginning beginners, to very established students and practitioners. So this is going to be a bit of a challenge for me. I’m hoping that this will become some sort of a discussion, rather than me taking up all the time talking.

To begin with, I’d like to talk about terms, because that’s somewhat important. I guess philology, you know language, is one of the driving forces of culture. And therefore, how human beings think and how we manifest is so much to do with language.

For instance, [consider terms] like “Buddhism” or “Buddhist”. This is quite a new term. I don’t think it exists in the sutras and the shastras. Was Buddha a Buddhist? I don’t think so. More likely, the English word “Buddhism” may have been invented by Europeans. I’m sure a lot of the academics here can really dig into this.

I’m mentioning this because somehow Buddhism is now categorized [as a] religion. For a Buddhist —see, I’m now considering myself as a Buddhist — for a Buddhist, it’s a bit like computer science or physics being categorized as a religion. In the past, [in] ancient India, seeking for truth, the universal truth, was very important. I guess it’s still [important] now. And the so-called Buddhists, Jains, Nyayas — those Indian philosophers and logicians, they were basically looking for truth.

Today we are using the term “dhyana”. Now this is a very important term, as the professor was mentioning earlier, but it is so difficult to interpret and translate1dhyana (Sanskrit: ध्यान, IAST: dhyāna; Pāli: झान, IAST: jhāna; Japanese: 禅, zen; Tibetan: བསམ་གཏན་, samten; Wylie: bsam gtan; Chinese: 禪, chán) = meditative concentration, meditation – see dhyana.. I believe the term “dhyana” later metamorphosed and became “chan” in Chinese, and “zen” in Japan.

Dhyana is a means, but not the end of Buddhism

Now, dhyana, Chan, Zen — these are all means. They are actually not the end [i.e. the goal of the Buddhist path]. So actually, even though dhyana is very, very important, in itself [it] is [of] secondary importance, because it’s just a means, not the end. I’m emphasizing this a little bit because mindfulness and meditation have become sort of fashionable now. But I think it is important to remember that actually meditation or mindfulness or dhyana, they are just methods. They are means.

If I’m having a coffee, the cup is the means. I can have it in a porcelain cup or I can have it in a paper cup, depending on different situations. If I’m travelling, probably a porcelain cup is not a good idea.

At times, what happens is [that] we put so much emphasis on the cup. Nobody is talking about the coffee. [Whether it’s in] a five star resort or some weekend retreat — yoga retreats, mindfulness retreats, anywhere — people put more emphasis on the means. So I’d like to take the opportunity this evening to really just remind ourselves that the end or the contents — what’s in the cup — is actually more important than the cup. If you have that clearly [in your mind], then the dhyana, the mindfulness, the training, the application has some sort of aim.

Now this is kind of important, but it is really difficult to grasp. Because I think when we talk about the end, we are usually talking about something so abstract. But the means can be something tangible. Such as the moment we talk about meditation, dhyana, we immediately, almost automatically, think in terms of sitting straight.

Calm and relaxation are important, but not the aim of Buddhism

And sitting straight has a lot of benefit. To begin with, it relaxes you. But is Buddhism really interested in relaxing? Ultimately? Meditation also has this connotation of being peaceful and harmonious and calm and all that. But, again, [things] like relaxation, being calm and peaceful, are not really the ultimate goal of Buddhadharma.

Now don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that being calm, peaceful, [and] unstirred are not important. They are very important. If you want see clear and pristine water that is [currently] filled with mud, not stirring the water is important initially. Not stirring [the water] and letting it be [can] help all the mud to settle beneath, but the mud is always there. Any time it can erupt [i.e. be stirred up and once again make the water unclear].

This is why the characteristic of dhyana or contemplation in the Buddhadharma always has two aspects:

• Peace, calming, abiding – shamatha;

• Insight, seeing the truth – vipassana.

So let’s just explore this dhyana a little bit more, in the context of shamatha and vipassana. And let’s try to sort of reflect [on] these based on what’s happening within our life, currently.

There is so much anxiety in our lives

In our life, we have so much anxiety. And I’m talking about myself, by the way. And we have such a good reason to be anxious. There are so many things to worry about and they’re all valid actually. Will our dreams come true? Will others like me? Will others like us? Will the people we care [about] be okay? Will we be humiliated?

Because we are so exposed. We are just like naked.

And many of these reasons are quite serious. and they are kind of unpredictable. This makes us even more anxious. And success and good times come a little bit, but the risk is almost permanently waiting somewhere. And we’re living in very crowded places. Our body, everything about us is so fragile, like a dewdrop.

Now, again, here, as you hear this you may think, “Oh, here we go. The Buddhists. Always pessimistic. The Buddhists are these harbingers, bringers of bad news to the world”. But this unpredictability and uncertainty also has a lot of good sides. We can use almost all the reasons to be anxious as reasons to be happy and calm and blissful.

Knowing the truth and seeing our lives with a bird’s eye view

But knowing the truth is fundamentally important, because this is the only way we can counter our anxiety.

For instance, in the modernized world, like today’s world, there’s so much loneliness. And there’s so much you alienation. And [there are] so many challenges in our world of relationships. And challenges in the world of parenting. So what relevance is there in this application called dhyana?

Dhyana is a means to really understand the truth, which is the end. The result. Dhyana also makes you see your life in the world with a bird’s eye view. Right now, we are looking at our life from one angle, a small narrow angle. We are looking at our relationships, our health, our well being — everything — from a very narrow angle.

The dhyana that is taught by the Buddha is really to train ourselves to look at our life and the world with a big picture.

(b) What is the truth according to Buddhism?

The truth was not designed by the Buddha

Okay, so what is this truth that we are supposed to actualize?

Now it is really important for you to know that these truths were not designed by the Buddha. For instance, the moistness or the wetness of the water is the truth of the water. The heat of fire is the truth of the fire.

If you know that water is wet, then when you don’t want to become wet, you know what to do. If you want to be warm or fry something or burn something, you know what to do when you see a fire, because you know the truth. So basically, we are talking about [this kind of] fundamental, mundane, basic truth.

So, how does Buddha see the truth?

(1) Anicca = uncertainty / impermanence

The Buddha or the teachings of the Buddha see the world as constantly changing. Actually “changing” is probably not the right word. Uncertain. This truth is universal. This truth is not made by Buddha. The uncertainty or the impermanence of phenomena. This truth existed before the Buddha and it still continues.

This truth is probably the most evident [of the three truths] for laypeople like us. [But] even though it’s actually the most evident, this is also maybe something that we miss all the time. For instance, our self. We think we are the same person that existed 20 years ago, completely denying that it has changed all the time.

Okay, this truth at a glance, as I said, probably is the most easy. It should be logically kind of obvious. It should be. But for many reasons, we just cannot grasp it. Sometimes we do grasp it, but in a very twisted way.

For instance, we like to accept change when we think in terms of improvement. So if you are not slender or if you are little bit bulky. We like to think that by going to a gym, we can make ourselves fit and slender and good looking. So when we think in these terms, we accept impermanence. But if a doctor says you have blood cancer or something, then it’s like “How? It’s not possible”. You think that it’s almost unfair.

But this is actually a very gross example, a very obvious example. There are so many of these [aspects of our self that are impermanent]. Our values. Our definitions. What we believe and what we detest. All this keeps on changing. Some change very gradually, others can change overnight.

This truth is one of the most fundamental truths that Buddha taught, sometimes known as anicca2anicca (Pāli: अनिच्चा) = impermanence – see anicca..

The purpose of dhyana is to help us become comfortable with the truth

Now coming back to dhyana. Dhyana is meant to make you accept this truth and really be comfortable with it, live with it, glide with it. That is what dhyana is for.

As long as what you do accentuates [or] brings awareness of this truth, it is dhyana.

So basically what I’m saying is you could go to a temple, sit in front of a shrine and sit straight for an hour and think about impermanence, it could work [as a practice of dhyana].

You could also go to IFC3The IFC Mall is a 74,000 square metres (800,000 sq ft), 4-storey luxury shopping mall on the waterfront of Hong Kong’s Central District – see wikipedia. and the Lane Crawford4Lane Crawford (Chinese: 連卡佛) is a retail company with speciality department stores selling luxury goods in Hong Kong and Mainland China – see wikipedia. shop and look at all those expensive goods, and think, “I may never use them. I may never have a chance to use them”. If you have that kind of awareness, [then] an hour of window shopping, even [an hour of] actually shopping is actually dhyana. Very much. We can call it a shopping dhyana.

If your mindfulness or meditation practice doesn’t make you more aware of the truth, it’s not dhyana

This is why a lot of the so-called mindfulness meditation that is kind of popular these days, if these [practices] are not bringing the awareness of the truth, such as anicca [then it cannot really be considered dhyana]. And if your one-hour mindfulness meditation is just to make you happy, relax, help [with] your stress, then that kind of mindfulness is equal to any kind of materialistic sort of recreation [or] fun.

You [could] just go shopping, and you know sometimes shopping does help your depression. Or you can have some pasta, and that also helps your depression. But the problem with these [methods] is there’s always a post-shopping depression, a post-pasta depression.

When you are going to one of those lavish dinners or rowdy parties, you can also bring this awareness that this may be the last time I’m doing this. Not necessarily [that] somebody might die, but also our friendships [might change]. You know, today we talk to them as if they’re the closest, as part of your heart, but tomorrow they [might] become a sworn enemy. This happens all the time.

So if you can really look into this, there is really nothing religious about it. There’s nothing mythical. Uncertainty, anicca, impermanence is not a myth. It is so raw and present and here and now.

Okay, how is this going to help? Now think about this. How is this going to help with our modern day problems such as loneliness, relationships, parenting, etc.? If you really contemplate, if you look into our loneliness [and] the real causes of loneliness, one of the main causes is not knowing the uncertainty. And this is [the case] with everything, just all our problems. If you look into [them], there is just so much [of an] unreasonable, blind, completely narrow angle view of things. We unreasonably expect that it’s going to work, that it is going to be there all the time. This just keeps the loneliness and the alienation bigger.

Dhyana is about facing the truth, rather than trying to distract and numb ourselves as we usually do

Okay just one more summary of dhyana.

Usually when we are lonely, when we are unhappy, when we are alienated, what do we do? Our main solution is we numb ourselves. Including Sichuan pepper and wasabi. But I’m not only talking about that. Social media is really to numb yourself, to distract yourself, to get hooked to something [other than your loneliness and unhappiness]. But then the problem is it makes it even worse.

So online shopping, Amazon, all of this is basically a method to numb us. And that’s where we are. This is what we do usually.

Dhyana does the opposite. [We] just face it. Look into it. Try to see the big picture. Try to have a bird’s eyes view.

So let’s say you are lonely. You are lonely because you’re only looking at something from your right side [i.e. you’re only looking at it from one narrow angle]. And that right [side only] vision is limited. So if you lose that, that’s it. That’s the end of the world. But suddenly if you do the dhyana and look from a bird’s eye view, you see right, left, front, back — there’s just no time to be lonely. So many options. So many doors. At the same time, because of the bird’s eye view, you’re also not blindly following any of these options.

I’m trying to explain the word dhyana and [also one of its two aspects5Ed.: DJKR explained at the beginning of the teaching that dhyana comprises the two aspects of shamatha and vipassana.] vipassana6vipassana (Pāli: विपस्सना) = special seeing, special insight, greater seeing – see vipassana., lhaktong7lhaktong (Tibetan: ལྷག་མཐོང་) = vipassana – see lhaktong., [which means something] like “seeing extra”, “seeing the real deal” so to speak.

(2) Dukkha = unsatisfactoriness

Okay, let’s go to the next truth.

This [first] truth of anicca, uncertainty, impermanence — that’s quite obvious. So we should be able to grasp this intellectually at least.

The next one is a little difficult, I think. The next one, according to the Buddha, he’s saying that actually nothing gives us 100% satisfaction. Whatever gives you satisfaction always has its other side that gives you worry.

You know, ice cream is nice. But then how about the six pack? You know all that [seemingly brings satisfaction] always has something with it. If you contemplate on this, it should be really obvious. But I think it’s slightly more challenging than the first truth. Because [you can] then challenge [whether it’s always true]. You can say things like “Oh, how about poetry? How about artistic expression? How about creativity?” [Do these things also have an unsatisfactory side?]

And even more challenging, “How about Buddhist practice?” What I’m saying is [this also applies to] the Buddhist path. Practice. The path is by nature flawed. This is what I’m saying. So this is a little difficult to chew, if you are Buddhist.

Basically what Buddha said is if you want to be liberated, the last garbage or trash you have to throw [out] is Buddhism. This is what he’s saying.

The future Buddha Maitreya, he’s Maitreya Bodhisattva right now, he said it’s like a boat. If you take a boat and reach the other shore, you abandon the boat, then hop onto the shore. Otherwise, if you’re still standing in the boat, you are not on the other shore.

Here, since many of you are Chinese, I’d like to just remind you of the Table Sutra or Platform Sutra by Master Huineng, which I was recently reading. That is a priceless text. If you want to know more about this second truth, it is explained there very well.

There are a few reasons why nothing gives us full satisfaction. One obvious one is the first [truth], uncertainty. Because everything is uncertain, things are never going to give you 100% satisfaction.

The other reason is actually related to the third truth, which I should tell you now. Nothing is how it appears to be. Because of that, nothing gives us full satisfaction. Again, in our mundane world, we tend to accentuate and exaggerate the partial satisfaction that we have. And we try to sell that and convince ourselves that it’s a good thing to pursue.

Anyway, the second truth is many times referred to as dukkha in Sanskrit or Pali. Again, as you can see, [when it comes to] this truth there’s nothing mystical, nothing religious, nothing like some sort of a revelation here.

(3) Anatta = nothing has a truly existing self

Now [we’ll talk about] the third truth, and then after that, maybe we can begin some discussion. The third one [is] probably the most difficult. And [when it comes to] the way to explain the third truth also, there are so many different commentaries.

Anyway, just for now, a very simple version. I’m sure many of you who are seasoned students and practitioners of Buddhadharma, you know [this]. But [this is] for the benefit of those who are new. And this is a really big one.

Basically, what Buddha is saying [is that] the third truth is that nothing has a truly existing self. [Everything is just] a few parts put together, and then [we experience a phenomenon]. For instance, like a table. You gather some parts together, use it as a table, and then it just becomes a table. But it does not have a so-called “soul” of the table or “self” of the table.

But everything has an order, by the way. Just because it’s orderly does not mean that it truly exists. Even in a dream, there is order. If you dream of taking a taxi from here to Kowloon, there is the beginning stage, the middle, and the reaching [the destination] stage. But just because there is an order doesn’t mean that your experience truly existed.

Now on this level probably most of you can sort of accept [this]. It becomes more complicated when this no-self theory is applied to self, the person. Then it becomes very [challenging]. That’s very personal, you know. You can say whatever you want to say about my table, my car, my carpet, my house – but me? There’s that.

But in Buddhism the selflessness of the person’s self is very important. Now this is habitually difficult to accept. [And] this idea of selflessness ends up sometimes [being] misinterpreted as negation. Buddhist teachings on selflessness or shunyata are not a negation at all. It is not negating any kind of appearance. Not at all.

If I’m chewing something sour, some of you who know what is sour will have saliva in your mouth. The sour thing that I am chewing hasn’t gone into your mouth. But still, this is how the cause and condition functions. For those who have never experienced sourness in their life, [then] no matter how much sour I’m eating, [there will be] no saliva. Nothing. Because [the] habit of sour doesn’t exist in his or her system.

This [third] truth is often referred to as anatta in the Sanskrit language.

(c) Summary

So now just to re-summarize again. Dhyana is a method. A method to make you see these three truths. To make you maintain seeing these truths. Maintaining this recognition of the truth is important. Because we have so many things and especially as I said earlier, we have the habit of numbing ourselves.

Okay, so how does the anicca I talked about earlier, and this dukkha and anatta, [how do they] really relate to today’s world? About loneliness. Not just loneliness. About management. About leadership for instance. I’m only mentioning this because when you go to a bookshop, half the bookshop is about leadership and management. No one has written a book about how to be led. Everybody wants to be a leader.

And the thing is actually this. Especially for those who are new here. If you are asking me what is Buddhism? What is the Buddhadharma? What is dhyana about? It’s really about being a leader.

I’m really not making it up. You can refer to many sutras. I only remember the Tibetan verses. [DJKR recites a verse in Tibetan]. Buddha said “You are your own master. Who else can be your master?”

So do you want to be a good leader? Do you want to be a visionary leader? Visionary? Ah, this is an important one. What is visionary? Anicca, dukkha, anatta.

When you know [that] everything is changing, [that] nothing will satisfy you, [and] nothing is how it appears — [then] you are the greatest visionary.

And everybody wants to control others. We are all control freaks. Well, let’s do it. But [let’s] do it with this vision, this planning. Because if you want to control [things] and if you even have a little deficiency in the first truth, the truth of anicca [you won’t be able to control things]. If you don’t fully accept the truth that everything is impermanent, you are not a good control freak. You cannot control [things]. Someone will control you.

So [these three truths are relevant to] everything actually. It’s very related to our our existence.

But that is not the real aim [of dhyana and the Buddhadharma]. The real aim is to go beyond [our ordinary worldly existence].

Okay, so this is sort of the outline of dhyana. Probably you’re too tired. Maybe we’ll have a break. If you still wish to continue, when we come back we will do short exercise of this dhyana based on a very classic method.

To a certain extent is will help [you to] read books about how everything is changing, how everything does not give you satisfaction.

But this dhyana method has been tested [by] trial and error for 2500 years. This is a big gift. And there are some very simple and unique methods to actualize these truths. So when we come back we will discuss this.

Should we have a 10 minutes break?

[END OF PART 1]

Part 2

(d) Buddhist Methods

There are many different methods in Buddhism

Okay, so dhyana is a skill. It’s a method. Methods are important. But [as] one great Zen master said, it’s like if you’re pointing a finger at the moon, the finger is a method. Now, there are countless methods. And we should really be glad that there are countless methods. If there were only one or two methods, many of us would be lost.

Some methods are more universal. Other methods are more exclusive to a certain tradition or to certain people. And you know, sometimes we human beings are a bit funny. We look at some other people’s method and laugh. Remember I said everybody’s only talking about the cup. Nobody talks about the coffee.

So for instance, if you go to a Japanese Zen [temple], let’s say Soto Zen or Rinzai Zen, the simplicity seems to be their method. So it’s like empty. There’s one statue, there’s one flower hanging there. You know, that kind of Zen. Now, rush to Kathmandu, a Tibetan temple. Completely chaotic. There are so many [things]. That’s what they prefer, so to speak.

And there are traditions that really sort of [place more] emphasis on sitting, sitting, sitting. But then there are others that also emphasize chanting. So I guess that’s why if you go to somewhere like Kathmandu, you see a lot of these monks and nuns with a mala, a rosary. Whereas if you go to Japan, most of the monks don’t really go round with a mala or a prayer wheel. They’re all there sitting.

Images of the Buddha are also methods

And by the way, it’s not just that. Even the image of the Buddha is actually a skill. It’s a method. I’m sure the academics here will know [this] very well, I think pre-Ashoka, the Buddhists had hardly any images. People like Mahayana people who read the Vajracchedika Sutra, they say that Buddha said “Those who see me as a form, they have a wrong idea”. They say stuff like that.

But there are different Buddha appearances also. If you go to a Chinese [Buddhist temple], the Chinese Buddha is slightly more plump-ish. And in the Indian Cholla and Gupta period, the buddhas have big shoulders and a big chest. And then the Greeks [were] probably the most ancient Buddha statue makers. Gandhara. They have a long nose, high nose. But these are all methods.

Sitting straight is a method revered by all traditions

Now there’s one method that all traditions, everyone sort of reveres. And that is sitting straight. I think it makes sense. You can do thinking about impermanence and [thinking that] nothing is really going to satisfy you 100%, all of that. You can do that on a hammock with a martini in your hand. You can. It’s not like you cannot.

But the chance of you falling asleep or getting more numbed is high, especially for beginners. So sitting straight is sort of revered. Not now, but [for] those who wish to explore this dhyana a little bit, I would recommend this.

(e) What is self?

The four aspects of self

Okay, so how are we going to do this? There are so many methods, but I’m going to choose one specific one tonight.

Let’s talk about me. Self. I. When we say “I” or “me”, who are you talking about?

Well, Buddhists think [that] generally you’re talking about four things: form, feeling, mind, and [for the fourth] Buddhists use the word “dharmas” but I’m going to use the word “references” for tonight.

So let me explain. When you say “me”, the moment when you say “me”, the outermost [thing that you’re referring to] is the size, the weight, the colour, the shape. Sort of very vaguely actually, very vaguely. You never ever really precisely know your body, even though you think you know. [The] body — that’s a big vessel. Let’s say, like an egg. This is a big shell.

Okay, now more important, but much more subtle, is feeling. Your feeling, that’s a big “you”. I’m hurt, I’m excited, I’m happy etc. I mean, [when the] body gets hurt, [that’s] already painful. But [when] feeling gets hurt, that’s much worse.

Now much more “you”, but much more subtle, is mind. Of course if you don’t have mind, you’re just a piece of wood or a piece of stone. You’re nothing.

Now, even more subtle, even more “you”, [are] dharmas or references. Let’s use [the word] “references”. Stuff like “I am a man”. “I am not 16 years old”. “I’m a nurse”. “I’m a doctor”. All these [are] references. This is a really big [subject]. I don’t think we can cover mind and references tonight. Briefly maybe [we’ll cover] the first and the second.

Thinking about the body

[Let’s] talk about your body. Usually when you think about your body, you think about Zara or Chanel or whatever. It doesn’t matter. Or yoga. Or the gym. Or Brad Pitt. I’m so outdated, so whoever is the [current] idol. Blackpink8Blackpink (Korean: 블랙핑크; commonly stylized as BLACKPINK or BLΛƆKPIИK) is a South Korean girl group consisting of members Jisoo, Jennie, Rosé, and Lisa – see wikipedia.. That’s what you think. The moment you think about your body, you think about these.

So what does that do? Remember? That makes you numb. That makes you forget anicca, dukkha and anatta. The three truths that I was talking [about] earlier.

Actually it’s possible to become like Blackpink, every one of us, but we will never think that. Even me, if my ultimate goal is a Blackpink body, I just go to Korea and [they will] operate. And probably I will have happiness for one week. But then things will fall apart. When I smile, I’ll have to really extra smile, because those plastics don’t move easily, you know. So that’s what I mean. So normally when we think about the body, we are always thinking this way.

Observing the body

Now let’s use dhyana. And let’s look at your body. But I’m not asking you to look at this body [and imagine that it’s radiating] light, [or] without light, in a special way – nothing, none of that. None of that. I’m not telling you to think of your body in a special way.

Just observe your body. As it is. Nothing more. Nothing less. One minute, two minutes, three minutes every day. Not using a specific [idea of] “This is how it should be, this is how it should not be”. Just observing.

We haven’t done this. Most of us haven’t done this. This is why you are never amused that you have ten fingers. It’s actually very funny that we have ten fingers and ten toes and stuff like that. Maybe some [have] eleven, some nine, I don’t know what. And nostrils. Oh my goodness. That’s like incredible.

So just that. Just observe. I’m not asking you to think about the Buddha or something holy, something compassionate. Nothing.

Confidence

That’s how you have to begin. Just observing the body. What does this do? This will make you [come] face to face [with] the body. If you are face to face with your body, without any judgment, without any references such as Blackpink, then at least it should really sort out the bulimia problem. Some people eat a lot and then vomit everything. Things like that. Overeating or not eating.

And you will not be proud of your body. You will also not be ashamed of your body. You will be confident with your body. Confidence with your body is much better than 100,000 Chanel lipsticks. Not only you are confident, but when you walk in here [or] there with your with your ease with your body, people will also be charmed by you, because you are not insecure. Your eyes are not rolling up and down.

Seeing the truth

But this is not our main goal. Our main goal is to see the anicca, the uncertainty of the body. The dukkha or the anxiety of the body. And the selflessness of the body.

Those who are seasoned, you’re doing a lot of practices and you’re doing many other things. But for those who just newly walked in today and if you’re curious about these [i.e. meditation], I highly suggest [you] to do this.

And usually you will also [think], “Okay, just observe body. And then what?” You might want to ask this. [There is] no “Then what?” Just keep on.

Observing feelings

Okay. I think we will quickly do the feeling. I think for beginners, you can also start with [observing] the feeling or the sensation of the body. There has to be a sensation, right this very moment. Just observing that. Then gradually, when you are depressed or when you are excited, just watching that.

When you are depressed, do not look for a solution. Just look at the depression. Observe and observe. Maybe it will take a few months. [But] if you just keep on being stubborn and observe your sadness, depression, anxiety, it will unfold to something.

Usually when we think about feeling, then we are always thinking about relationships, social media, some sort of a way to numb [them]. But here it is the opposite.

Make your practice short but consistent

Sorry, it has been really longwinded. Somehow it ended up becoming quite long. I’m going to wrap this here.

I would suggest [for] those who want to do it, do it short. I’m talking about two or three minutes. Even if you want to impress your friend [by] doing one hour, don’t do it. Especially if you’re a beginner. But be consistent. The worst is doing some sort of Vipassana [retreat] for nine days, and then never doing it for [the next] two years.

If you do it every day [for] maybe two to three minutes, what will happen is you will then [experience] when they call “the taste of samadhi”9samten gyi ro (Tibetan: བསམ་གཏན་གྱི་རོ་) = the taste of samadhi – see samten gyi ro.. And then once you reach that, you will always be looking for this taste. The moment you have any spare time, you will want to taste that.

So this is just a very brief introduction to dhyana. I was trying to make it more practical.

But I want to really tell you this. Let’s make it a little broader. I will consider those of you here who go to temple. [Let’s suppose that] you do not sit. You do not think about everything that I just said. You [simply] offer an incense and think “I [would] like to really actualize dhyana”. This act, I would consider [it] as dhyana.

Okay, so maybe we will have something like five questions. I heard there are some questions from outside I think.

Q & A

There are so many teachings out there. How should we choose which one is best?

[Q]: Nowadays, there are many lectures about Buddhism and also [about] meditation in the market, especially during these [last] two years. So for us, especially for Vajrayana students, how to make a choice? Which lecture, which class should we take? Because time is kind of limited, but every day we have so much information on the different classes and lectures, so could you give some suggestion? How to make a choice? [What] is the best way for us?

[DJKR]: If you are beginners, you should watch all. Just fast forward wherever you are bored. Just fast forward. I’m serious.

[Q]: But time is limited.

[DJKR]: Well, yes, but I think you’ll have to bump into one that you will be hooked [by]. So until then, you could just go through [them all] and then one day there will be something that will really [hook you]. Karmic link, they call it. That may happen.

[Q]: So even if I already have a guru, do I also need to listen to different teachers or gurus?

[DJKR]: You don’t have to, but sometimes we do because, you know, we like to see what some [other] people are saying.

What is the “taste of samadhi”?

[Q]: Thanks for your talk. I’d like to ask one question. [You mentioned the] taste of dhyana, and you also talked about the body, mind, feeling and dharmas.. So when you talk about the taste, is this is a taste from the body, feeling, mind or dharmas?

[DJKR]: This is an important question. In Tibetan we call it samten gyi ro10samten gyi ro (Tibetan: བསམ་གཏན་གྱི་རོ་) = the taste of samadhi – see samten gyi ro., meaning the taste of samadhi. I’ll give you a very crude example.

What is the main purpose of dhyana? The main purpose of dhyana is really to topple, to destroy the duality. You know, right-wrong, bad-good, all that. This duality is so tiring and exhausting. Now I’m not promoting alcohol here. But I have to give you some sort of a crude example. Why do people drink? Why do they like this tipsy feeling? They like this sort of very fake nonduality. A little bit of a “couldn’t care less” [attitude]. You become more bold. You’re less afraid. You don’t really have too much burden of being good. Which many [people in] Chinese society suffer [from].

So this is why we do this, right? Now, multiply this one million times. Without needing to buy alcohol. Without needing to become addicted to a substance. You know, some sort of a sense of boldness. Not that worried about being good. But of course, also not upsetting everybody by being bad. And also in the past, maybe you [were] so obsessed with things, like you have to iron your underpants. Now, maybe you don’t even wash it for a few days. You know what I’m saying? That kind of relaxed, couldn’t-care-less-ness. Maybe that is a sort of a mediocre example for this taste that I’m talking about.

If nothing has a true self or nature, what about Buddhanature?

[Q]: I think just now you mentioned the third truth, which is about selfless. I found it a big crash [Ed.: i.e. challenge] to the concept of the Buddhanature, like Buddha reference. So, as you said, everything is selfless. But what about the the nature itself, the Buddhanature itself? I just feel a little bit confused.

[DJKR]: This is an important question again. Yes. There are so many extensive [studies] on this. Buddhanature, Tathagatagarbha, is a label. And it’s a very carefully crafted label. So many people [were] involved trying to sort of define this.

This is also a little complicated question by the way. I’m going to give you my standard example I usually gave. [You] see, for example when you are reading the Heart Sutra, there is a lot of mention of shunyata11shunyata (Sanskrit: शून्यता) = emptiness, lack of true existence, illusory nature (of all worldly phenomena) – see shunyata., “No this, no that, no eyes, no nose, no this, no Buddha . . .”, you know?

But this “No”, the word “shunya”, it’s actually not a negation “No”. By the way, the Indians are very proud that they came up with the word zero, right? It’s very difficult to translate this word “shunya”. In Tibetan they translate it as tongpa nyi12tongpa nyi (Tibetan: སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་) = shunyata, emptiness – see tongpa nyi.. Tongpa13tongpa (Tibetan: སྟོང་པ་) = blank, empty, nothingness, devoid; also used as synonym of tongpa nyi (emptiness) – see tongpa., okay, but this word “nyi” has everything14nyi (Tibetan: ཉིད་) = (1) -ness, [used to form abstract nouns ; (2) it, itself, the very, the same, namely, just, only, exactly ; (3) self, itself, oneself ; (4) nature – see nyi..

So how do you talk about something that is yes and no, both together? It’s bit like a rainbow. It’s there but it’s also not there. There is a scholar called Nagarjuna, I’m sure many of you have heard [of him]. Maybe his commentary is more on “It’s not there”. And [other scholars such as] Asanga or Maitreya are talking about the same thing, the rainbow. But their interpretation is more that “It is there”. So basically what I’m saying is that Nagarjuna people will use the word shunyata more, and Asanga people will use the word Buddhanature more, Tathagatagarbha15Ed.: when DJKR taught the Uttaratantra-Shastra, he said (p.3):

You could say that when Nagarjuna explains the Prajñaparamita, he concentrates more on its ‘empty’ aspect, whereas when Maitreya explains the same thing, he concentrates more on the ‘ness’ aspect.

From “Buddha-Nature – Mahayana-Uttaratantra-Shastra” by Arya Maitreya with commentary by Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, Siddhartha’s Intent, 2007.. So, it’s not really a self.

How should we observe negative feelings like depression or anxiety without spiralling out of control?

[Q]: You said [we should] observe difficult feelings like depression or anxiety, rather than trying to find a solution. So how do we keep afloat and separate ourselves from the experience, and prevent ourselves from sinking and spiralling out of control? Are our feelings separate from our mind?

[DJKR]: Yes, a little bit of patience is required now. I know we live in a culture, we live in a time where there’s lots of Panadol. Quick fix. I understand that just observing the sadness for just a few days may not do the job. But [you] should be really persistent.

Yes, if [you] could just put a little more effort in just observing. But when you do just observing, a few other obstacles will arise. When you do just observing, the feelings are still so strong. The sadness, the depression is so strong. You’re still observing. And part of you wants to just fix it. That is one of the problems. So please try not to fix it.

There’s another bigger problem. Sometimes when we observe, actually the sadness dissipates. Then you get excited. You think, “I did it”. That’s even more dangerous. So no giving yourself an award.

And then of course, also, it’s very boring. So you will have to really learn to love the boredom. That’s why I’m suggesting three minutes. And please don’t tell me you don’t have three minutes. You do have three minutes.

Okay, two more questions and then we’ll finish.

When we observe the body, should we literally take our clothes off and look at our body?

[Q]: A lot of students in mainland China would like Rinpoche to explain a little bit more about observing the body. Do you mean literally take our clothes off and look at our body?

[DJKR]: That could help actually. But I think more important is just sitting and just acknowledging the body. Okay. [During the] whole day today, how many of you have thought about your body? I know you shat many times. I know you drank many times. I know you talked many times. But how many of you have thought about your body? Just for even a minute? That’s all we are talking about. Yes. Observing, acknowledging.

Okay, one more and then we will end here.

Does true love really exist?

[Q]: I have an important question. [If] everything is impermanent, then love is impermanent. So I really want to know, how do you think about love? Does true love really exist?

[DJKR]: Does true love exist?

[Q]: Yes. What is true love?

[DJKR]: This is really important. No, I’m serious. We should all love others and we should all be loved by others. We should. And anyway, when love comes, nothing can stop you. When the karmic wind blows, it doesn’t matter. You could be sitting here in Hong Kong, your lover will be in Bolivia or in Peru. Something will just happen.

And here, what I said earlier about anicca and impermanence, what you just said, it’s just so good for love. If you are looking at your lover with this [attitude that] this may be the last time you are looking at [them], I think you’ll be more openminded. You’ll be more forgiving, even if he has chewed raw garlic.

And because of this training, the next day [if] your lover is looking at someone else, you are already quite prepared. And because you are prepared and you are confident, he becomes a little insecure. This is the best way. This is the art of the game, isn’t it?

Basically as long as there is an illusion of self and we are attached to this illusion of self, yes, there’s always going to be something called “love”. And then if it is coming towards you, let it come. And no need to be too worried about it. Because love also involves a lot of surrender. And yes, even though probably you love somebody the most, complete surrender is difficult for human beings. Because you can always [say] “I really love you and I surrender to you”, but is he or she really doing this much? So there’s all that kind of negotiation.

So with this very auspicious word “love”, we will conclude this time. I’m sorry it has been a bit too long. I pray and have aspiration that you will have a lot of love.

[END OF TEACHING]

Note: to read footnotes please click on superscript numbers

Transcribed and edited by Alex Li Trisoglio