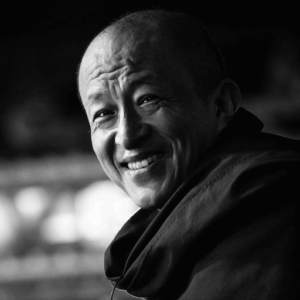

Alex Li Trisoglio

Madhyamakavatara Week 4: Refuting Mind-Only

Week 4: Refuting the Chittamatra (Mind-Only) school

28 June 2017 / 111 minutes

Question: How should we understand the Buddha’s teaching that all things come from mind?

Reference: Madhyamakavatara verses 6:45 – 6:119

Transcript / Pre-reading / Audio / Video

Review of the first three weeks [Audio/Video timing: t = 0:00:00]

Good evening everyone, and welcome to Week 4 of Introduction to the Middle Way. I’m Alex Trisoglio, and I’d like to start by reviewing the first three weeks, just to remind us how we got to where we are right now.

So firstly, what are we even doing here? Why do we need to establish the view? The first reason is that we’re here because we wish to liberate ourselves and all sentient beings. So the purpose of our study here is not academic, it’s not to write books or to write PhDs, it’s so that we can liberate ourselves and others. And that involves realizing the truth. And as Rinpoche has said many times, the truth can be expressed in terms of the Three Marks or the Four Seals. So once again, these are:

• dukkha (suffering or unsatisfactoriness);

• anicca (impermanence);

• anatta (non-self); and in the Mahayana we also have the fourth seal:

• nonduality

This is the truth, these four marks or seals that describe the nature or truth of reality. And wisdom or prajña is seeing or knowing this truth. If we don’t know the truth, or even if we know it intellectually but it’s not what’s driving our actions, then we suffer. And in Buddhism, suffering has nothing to do with sin or punishment. It’s mainly to do with ignorance – not seeing the nature of reality and the nature of the self. So to end suffering for ourselves and for others, and to attain lasting enlightenment, we need to realize this truth. This means we need to establish and then realize the right view, so that we have a path that can lead us to enlightenment.

So that brings us to establishing the view, which is what we’re doing now during this course of study. The ultimate truth is nonduality. It’s beyond words, beyond thoughts, beyond concepts. It can’t be taught. It can’t be expressed. So we can’t actually study that. All we can study here is the textual Madhyamaka, the ‘finger that points towards the moon’.

Nonduality [t = 0:02:43]

As we saw in Week 3, Jigme Lingpa said:

As soon as we talk, it’s all contradiction;

As soon as we think, it’s all confusion.

So we have to acknowledge that there’s an irreducible amount of confusion that’s going to accompany everything we do. And as Rinpoche has said so many times, realization can only be accomplished through our practice, through our meditation, because our words, our thoughts, our language – they can get us as far as rational understanding, to dualistic understanding, but can never take us beyond to nonduality.

And Chandrakirti explains that he can’t enter the sutras, the Buddha’s teachings, directly, so he’s going to teach based on the shastras, the commentaries on the sutras. He’s going to base his teaching on two texts in particular, one is Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika and the other is the Dashabhumika-Sutra. And although it may seem like our topic is ultimate truth, actually a lot of what we’re going to be studying is the post-meditation time of the bodhisattvas on the bhumis. And in particular now we’re in the sixth chapter, the sixth paramita, which is prajña or wisdom. The Tibetan word for prajña is sherab, which means ‘supreme mind’. And what does this supreme mind know? It knows that any dualistic thought is not the supreme mind. And it therefore wants to go beyond dualism and realize this nondual. So we know that anything we look at as a temporary phenomenon cannot be the ultimate or supreme mind, because it is changeable. And that’s part of the reason that we’re concerned about any of our opponents establishing anything as truly existing, because if you have a truly existing object, then by definition it must be duality that you’re talking about. Because if an object were truly existing, then it would have to be independent of all other phenomena – including any possible subject – which would mean that subject-object duality would be part of the ultimate truth of reality.

So what is the Madhyamaka view that we wish to establish? As we saw in Week 3, it comprises the Two Truths:

• In the ultimate truth, all phenomena are beyond extremes – indeed, there is no arising and ultimately we cannot even say there are any phenomena.

• In the conventional truth, we accept the conventional consensus of ordinary beings.

In the verses that we’re going to cover this week, Rinpoche emphasized that the conventional truth is not a thesis. It’s not like the positions of philosophers and theoreticians. Because as we know from our own experience, as ordinary beings our views change all the time. One day we explain things one way. Another day we explain it differently. We don’t have solidly, firmly established views in the conventional world. But we nevertheless still have the innate ignorance that our self truly exists, which is the basis for our self-clinging and our hope and fear, and which leaves us wandering lost in samsara. And worse, we encounter theologians, philosophers and theoreticians who set out other views of true existence – of the true existence of God, or the self, or phenomena like truly existing atoms or truly existing consciousness. This imputed ignorance adds another layer of delusion on top of our innate ignorance, and this imputed ignorance is what Chandrakirti is going to help us refute in the Madhyamakavatara.

Chandrakirti is going to establish the Madhyamaka view by refuting all theories of truly existing arising – all the theories of arising from truly existing self or other or both or neither – because all theories that believe in truly existing arising are extreme views or wrong views. They are dualistic views, and they cannot be used as a path to lead us to the wisdom of nonduality. Last week, in Week 3, we covered the Samkhya school that believes in arising from self, and we also looked at other-arising in general. This week we’re going to turn to the Chittamatra school (the Yogachara), which is a specific example of a Buddhist opponent that believes in truly existing other-arising.

Review of Week 3 [t = 0:06:34]

I’d like to review what we covered last week:

Self-arising (6:8-6:13): I won’t spend long reviewing self-arising. As Rinpoche said, it’s not something that concerns us much in the modern world, because for most of us, when we think about causality or arising, we think that the cause and the effect are different. We don’t think that the cause and effect are the same, which is what you’d need for truly existing self-arising. We’re much more likely to fall into describing things in terms of other-arising, where we say there is a cause (like a seed) and an effect or result (like a shoot), and they are different. We say that the seed is different from the plant that it gives rise to.

Other-arising (6:14-6:22): As we refute theories of other-arising, we’re going to meet – indeed, we already have met – a number of Buddhist opponents. In the verses we covered last week, our opponents were suggesting the possibility of truly existing other-arising. What does that mean? It means we have a truly existing cause that gives rise to a truly existing effect. Let’s just remind ourselves, what does it mean to say that something is ‘truly existing’? It means that it is independent and it is unfabricated. We gave the example of a billiard ball or a marble – that is a good example of something that might represent or symbolize true existence. A marble has nice hard edges and clearly defined boundaries. It doesn’t change. Whereas if we wanted an example of something that’s not truly existing, in other words something that’s dependently arising, maybe we think of a cloud. Compared to a marble, a cloud is much more fuzzy and much more changeable. Even as you watch a cloud in the sky, you can see how it changes. But a cloud is not a good example of a truly existing phenomenon, because for something to be true, it can’t change. It can’t be changeable. And that, by the way, is why it must be independent, because if a phenomenon depends on something else, then it could change. And likewise, we want it to be unfabricated, because that way there’s no fabrication or imagination or conceptualization that is going to affect this phenomenon. It’s not something that has been imagined, or labelled, or imputed by a theoretician.

Refutation of truly existing other-arising [t = 0:09:12]

When Chandrakirti turned to this position, he said that truly existing other-arising is impossible. Firstly it would mix up the order of cause and effect. Because if the two things – like two marbles – that comprise cause and effect are truly ‘other’, then things could arise of a different type or they could arise unpredictably. The logic of causality, of cause and effect, would fall apart. This is because there’s nothing that would connect our two marbles. There’s nothing that would ensure there is some order to the way they interact.

A second refutation was in terms of time, because if we have our cause and our effect present at the same time, like our two marbles, then we can’t say that one is the cause and one is the effect, because they’re both there already. But if we don’t have them there at the same time, then they have no contact One marble can’t hit the other marble. So if they’re not there at the same time, how could a cause lead to an effect?

Our opponent is aware of these problems, and suggested that the reason things arise in an ordered manner is because they form part of a ‘continuum’. For example that rice seeds only give rise to rice shoots, never to barley shoots. But Chandrakirti refuted that by saying, well that’s a circular argument, because really all you’re saying is ‘Things in the same continuum cause results in the same continuum’. So our opponent is really just re-stating what they just said. It’s not actually any kind of proof.

We’ll see that kind of argumentation come up again today. Because with the Chittamatra, a lot of the challenge is going to be that they believe in a truly existing subject, a mind or consciousness, but in their view the objects that are perceived by this mind are not truly existing.

We are inconsistent [t = 0:11:20]

While we’re on the topic of true existing, let’s not forget Rinpoche’s observation about how inconsistent we are when we tell stories about the things that happen – and why they happen – in our everyday life. I also noticed this same tendency, by the way, in the questions that many of you asked during the week. In the Madhyamakavatara, Chandrakirti talks about how our opponents believe in truly existing other-arising. And as we seek to understand the meaning of the text, we try to relate it to examples from our own experience. So we might say ‘Well, an acorn gives rise to an oak. An embryo gives rise to a baby. Where do we draw the boundary? There is no hard boundary. How could we say these things are truly other? We cannot say this is truly existing other-arising.’ And yes that’s fair. But the point is that if we’re thinking in this way, we’re now taking Chandrakirti’s position. We’re saying there is no such thing as a hard boundary around these everyday objects in the world. We don’t see them as truly existent causes and effects like marbles. So we’re no longer taking our opponent’s position. And as we said last week it’s actually very difficult to find a coherent way of talking about a truly existing other-arising.

And that’s all very well in theory. We might convince ourselves that Chandrakirti is right, and our opponents’ views really don’t make any sense. But of course in practice things don’t quite work out that way. As soon as something unwanted happens in our lives, or we lose something that we care about and value, we very suddenly become eternalistic. When someone steals our money, we don’t generally think in terms of causes and conditions coming together. We don’t tend to think of all things being compounded and impermanent. We tend to think we’re victims of a crime, and a real crime – a truly existing crime – at that. We solidify. We cling. Likewise, we aren’t looking for love that’s impermanent and fabricated. We don’t want a fake love. We want true love. Real love. And if popular music is to be believed, many of us think we’ve found it.

So while it may seem obvious while we’re studying that these ideas of truly existing other-arising cannot be realistic in the world, we haven’t yet realized this view. Our Theory-in-Use – the mindsets that actually drive our action – haven’t yet caught up with our Espoused Theory. Our view isn’t yet firmly established. And as we have been saying for the last three weeks, establishing the view is critical. We need to know what is the right view. But 98% of the work is practicing the path, because it’s one thing to know something intellectually, and it’s another thing entirely for it to be realized, internalized, and embodied in one’s being in the world.

The Two Truths [t = 0:13:34]

The next big idea that we were introduced to last week was the Two Truths. And as you may recall, this started from a question that our opponent asked: ‘Well, Chandrakirti, you say that you accept ordinary people’s view on conventional truth. And yet you’re trying to refute other-arising, when most ordinary people would say that cause and effect are different – as we’ve just seen. They would say that the effect arises from the cause, and the effect is different or other than the cause. In other words, they believe in other-arising. So why won’t you accept their view, like you said you would?’

So to answer this challenge, we set up the idea of the Two Truths. Bear in mind that the Two Truths don’t truly exist. They themselves are just another convention, another useful boat to cross the river, which we shall eventually abandon when we reach the other shore. We’re not saying they’re ultimately there. And when we distinguish the ultimate truth and the conventional truth, we define the conventional truth as corresponding to the commonly agreed ways of talking about things in the everyday world. The conventional truth is not a thesis or view that is articulated with philosophical precision and that speaks of truly existing phenomena. The conventional truth is imprecise and untidy. It’s an approximation. It’s a means of communication. It’s something that we need to know and get right in the world, because we need to be able to use ordinary language and cultural norms when we talk to ordinary beings. But that doesn’t mean we accept their theories of what is ultimately true. And by the way most ordinary people don’t actually have theories of what is ultimately true. Most of our ignorance, our clinging, and our attachment is fairly implicit and fairly intuitive. We have a pre-verbal and pre-conceptual sense that ‘I am here. I have a self’, and then we cling to this self, giving rise to ‘me’ and ‘mine’, to attachment and aversion, to hope and fear, and to all the conventional dualistic phenomena of our everyday lives. But these views are not usually established through any kind of logical reasoning, unless we adopt philosophical and religious beliefs like those of our opponents.

We also learned that we need to realize both of the Two Truths. We need to realize the ultimate truth that all phenomena are completely beyond any extremes of existence, non-existence, both or neither. And in the relative truth, we just accept the conventions of ordinary people. Because if we don’t realize both of the Two Truths, we’ll end up with an extreme view. And most typically we’ll end up in the same situation as most of our opponents – they assert something truly existing in the ultimate truth, which is a form of eternalism, and they deny something that is accepted by ordinary people in the conventional truth, which is a form of nihilism.

Whereas, as we saw last week, because Chandrakirti accepts the Two Truths, he doesn’t have these extreme views and he avoids the pitfalls of eternalism and nihilism. Moreover, when it comes to all the confusion that other schools encounter when they attempt to explain causality, especially causality over time and space, Chandrakirti has no problem. He has no truly existing cause, and so there is no truly existing end to his cause. So there’s nothing that he needs to connect to the result, because all of his causes and all of his results arise dependently anyway. It’s not as though there is an clear end or a clear beginning to any of them.

Intellect and emotion [t = 0:16:49]

Rinpoche also talked about the challenge of aligning our emotions and our intellect when it comes to the Two Truths. A big part of the challenge of the teachings on emptiness and the Middle Way is that our experience doesn’t match up with what the teachings say is real and true. We may know intellectually that there is no truly existing self, but we don’t feel that in our subjective experience of the world. We feel, ‘Hey, I’m really real. I’m here’. What we know intuitively doesn’t match up with what we’re supposed to understand intellectually when we read the Madhyamaka texts. So what do we do? Well, either we ignore the theory, or else we have to conclude that our feelings must be in some way wrong and unreliable. Of course this is very tough because we have been repeatedly told, ‘trust yourself’, ‘trust your feelings’. That’s pretty much the theme of the main song in every Disney movie.

Part of our challenge is this dilemma: are we going to follow our feelings, or are we going to follow the truth? And that’s always difficult, because the intuitive move will always be to go with our feelings, to go with our gut. So as we said in Week 1, it’s very important for us to really develop the view, to establish the view for ourselves, so it doesn’t feel like some external set of rules, but it’s something that we can understand and believe and then internalize for ourselves.

So let’s go back to the mismatch: What we feel may not match up with what we know to be true intellectually. But rather than focussing on this discrepancy, the Two Truths comes out in a different way. It says, well, ultimately there is a truth of how things are in reality, and then conventionally there’s a truth that corresponds to our feelings, our subjective reality. As Rinpoche said it’s like relationships, like conflicts. Whenever there’s a conflict between two people, there’s the objective truth of what actually happened – who said what, who did what. And then there’s the truth of each person’s subjective experience. And we all know, because we’ve all done this, that we can take things the wrong way. We can take things personally. We can perceive an intention that wasn’t actually there and thus we feel bad or upset with another person. Or sometimes we feel good. Sometimes we may have assumed that someone has been attracted to us when in fact that wasn’t the case at all. So we’re always imputing this kind of intentionality to others.

Subjective and objective [t = 0:19:18]

And so an important practice, even in the contemporary world, is separating the other person’s behaviours – what they actually said and did – from our interpretations, feelings and reactions. Separating the truth of what actually happened from our personal subjective experience. If we look, we can always find the sense of an objective and a subjective. They’re maybe not exactly the same as the ultimate and the conventional truths, but I would say very closely related.

I have a personal story here. I sound very English, indeed I grew up in England, but I was born to an Italian father and a German mother. And so I don’t know if you know much about the difference between the Italians and the English, but one thing is how they communicate. In Italy conversations are typically a source of great ebullience, energy, with people talking over each other. There’s a very extroverted, high-energy kind of feel to a conversation. Whereas in England it’s considered polite to listen carefully and wait until someone has finished speaking, and then speak yourself. And so if I were in England, I would say well, if you interrupted me – if that was the behavioural truth that I observed – my subjective experience would be, well I’m very upset because it means you didn’t listen carefully to me. It means you weren’t actually paying attention. So I would take that in a very bad way. Whereas in Italy if you interrupted me I’d say ‘Fantastic, it means you’re really excited, engaged, enthusiastic’. And so there you see how you can have the same truth perceived very differently by two observers. This is something that is happening everywhere in our conventional world.

So the first aspect of the two truths is that we have an ultimate truth and a conventional truth. And there is a third element we also discussed last week, which is about disagreements on the level of relative truth. The conventional truth is a valid relative truth, it is where there is a consensus among ordinary beings. We also identified the idea of an invalid relative truth. When for example if somebody has taken too much alcohol or drugs, or if they’ve got some kind of eye disease where they see falling hairs – because in that case their perception would not be the same as the perception of other conventional beings. Their perceptions would be an invalid conventional relative truth, not conventional. And what Chandrakirti is going to say, and has already said is, is that all our opponents’ theories of true existence and true arising are invalid relative truth. They’re not conventional truth, because not only are they positing an ultimate truth that conventional people don’t agree with, but also because of their theories they’re denying some aspects of the conventional truth. An example we gave last week was: If a person says, ‘oh my goodness I just broke one of my favourite wineglasses’, a materialist might say, ‘that doesn’t matter. You didn’t break a glass, it was just a bunch of atoms!’ That’s an example of a denial of the conventional.

I’d like to add another example here, which we’ll come back to in Week 8. It’s a lovely story, called the Stockdale Paradox. It’s the story of Vice-Admiral ➜James Stockdale, who was the highest-ranking American military officer to have been captured and held in Vietnam during the Vietnam War. He was held for seven years in a prisoner of war camp, and suffered almost intolerable conditions: torture, sleep deprivation, all kinds of things, but he survived. And when afterwards he was asked how he did it, he said that his practice was to do two seemingly paradoxical things together at the same time. First, you have to face current reality. See the truth. Don’t deny it. Don’t hide from it. Admit to yourself very honestly: this is what’s going on. But then also to have confidence that you will prevail in the end.

This is not exactly the same as the Two Truths, but it’s a very similar notion that there’s a part of you that needs to be focused on the truth of your current situation. And there’s another part that’s very much around possibility, optimism, compassion, what could be, hope, faith. I think it’s a good invitation for all of us as we look at that balance in ourselves. Do we veer towards focusing a little too much on the reality with not enough optimism? Or do we focus a little bit too much on the optimism and not really pay enough attention to the reality? Because either of those would be an example of not practicing the Two Truths.

What is the best teaching for a particular person? [t = 0:24:39]

Another important point that we came across last week is the idea that any provisional teaching is not the ultimate truth. So all the provisional teachings are untrue in some respects. And as we said, all the teachings, all the paths, all our language, all our communication is in some way faulty, as Jigme Lingpa said. This applies even to the teachings themselves. Yes we know that the emptiness teachings are seen as the highest, they’re seen as pointing to the ultimate. But all the other teachings, teachings on compassion, teachings on the paramitas, teachings on kindness and patience, teachings on Buddhanature – all these things are provisional. They’re seen as just a means to lead us to the ultimate. We might be shocked to hear that teachings on compassion and Buddhanature are considered ‘only’ provisional. But as Rinpoche emphasized, we must never look down on the provisional as being worse. Because it’s all about what is skilful, what is useful, and what is the right path that can lead us to the right view. If we give someone the wrong teaching at the wrong time, it’s not going to inspire them to travel in the direction of the truth. They might give up, lose inspiration or even abandon the Dharma entirely. As we saw in Week 2 (verses 6:4-6:7), although the teachings on emptiness are considered the highest and most direct teachings, we should not teach Madhyamaka to somebody who does not have a strong foundation in meditation, mind-training and compassion, because then they might easily misunderstand the teachings as being teachings on nihilism.

There’s a lovely Zen story that illustrates skilful communication. It’s called Time to Die, and appears in the collection of 101 Zen stories:

Time to Die

Ikkyu, the Zen master, was very clever even as a boy. His teacher had a precious teacup, a rare antique. Ikkyu happened to break this cup and was greatly perplexed. Hearing the footsteps of his teacher, he held the pieces of the cup behind him. When the master appeared, Ikkyu asked:

“Why do people have to die?”

“This is natural,” explained the older man. “Everything has to die and has just so long to live.”

Ikkyu, producing the shattered cup, added: “It was time for your cup to die.”

As we saw last week, Rinpoche and J. Cole both talked about three different kinds of students or listeners. Some can hear the truth at once. Some need repetition, and then eventually they hear it. And for some, you can repeat the truth as often as you like, but they won’t be able to hear it until they’ve had more life experience.

The forest glade and the charnel ground [t = 0:27:09]

Another question is what kind of practice to teach someone, what is the best? And likewise, for ourselves, what practice is the best? When answering this question, Rinpoche often talks about the difference between the forest glade and the charnel ground. If you go back to the Pali suttas, the Buddha talks about an ➜ideal meditation spot as being away from the chaos and distractions of the city, and that we should find a quiet secluded place in the forest to practice. And indeed that’s very beneficial, especially if we’re easily distracted or if we’re beginners. And yet we also know that tantric practitioners consider that the most auspicious places to practice are charnel grounds, which are traditionally believed to be full of all kinds of spirits and strong energies and very distracting forces. These would be terrifying and distracting for a beginner, but if one is a stronger practitioner, then the forest glade is not going to help one move forward with one’s practice.

It’s a bit like skiing. As a beginner, you want to learn on the most gentle slope, the greenest of the green runs. If you put a beginner on a steep and dangerous black run before they know what they’re doing, they will quite likely fall over and maybe even break a leg. But for somebody who’s an advanced skier, if you make them go down a green run, it’s one of the most frustrating things. It’s boring. It doesn’t test their skills, and it doesn’t help them progress any further along their path. So we need the right kind of path for the right person, in Buddhism as in skiing. In Week 2 we learned about how should teach emptiness to different kinds of people (verses 6:4-6:7), and Chandrakirti recommends very different approaches depending on a person’s capabilities and experience on the Buddhist path. For some people – those for whom tears come to their eyes and their hairs stand up on edge when they hear about emptiness – for them, we should teach emptiness directly. But for many beginners, it’s much better to teach them a gradual path of mind training, shamatha and vipassana, and bodhicitta – and only introduce the teachings on emptiness once they have developed a strong foundation.

Not deceiving oneself [t = 0:29:11]

An important part of finding and practicing the right path is not fooling oneself. As we learned in the Stockdale Paradox, we cannot afford to lose our inspiration and faith in ourselves and our path, but we also need the discipline to be honest with ourselves and realistic about our current capabilities and situation. Rinpoche’s number one piece of practice advice for beginners comes from one of Milarepa’s songs, where he says:

My religion is not deceiving myself and not disturbing others.

This ‘not deceiving myself’ – it’s very important. In particular, as Rinpoche often points out, who among us would want to choose a ‘lower’ path when a ‘higher’ path is available? What counts as a higher path in Buddhism is the extent to which the path reveals nonduality directly. If a path teaches nonduality directly, that’s considered a higher path. And when emptiness and nonduality are taught in a very indirect way, that’s considered lower. As Rinpoche says, you can summarize the whole Dharma path by saying ‘the non-truly existing (or illusory) person follows a non-truly existing (or illusory) path to attain a non-truly existing (or illusory) result’. And that is true. But who could understand this? Rinpoche even says that all the Buddha actually needed to teach was ‘you are all Buddhas’. It’s true. If we had the right capacities, we could hear this truth and it would liberate us. But again, most of us have no idea what the Buddha is talking about when he says this. It just doesn’t touch us. It probably sounds a bit like when our fitness instructor is trying to motivate us, and she says ‘You can do it!’ Most of us simply aren’t able to hear the truth when it’s presented directly. And that’s why the Buddha teaches 84,000 different paths. As Rinpoche says, that’s a sign of the Buddha’s tremendous compassion. He doesn’t just teach the Dharma in one way. He has a teaching that is perfectly suited to us, whatever level we’re on.

Especially now in the West, the idea of customer experience is very popular. We like the idea that we deserve the best. We only want the best. And when it comes to Dharma, we’ve heard that Dzogchen is supposedly the highest path, so everyone says, ‘I want Dzogchen, I want mahamudra, I want mahasandhi’. And of course there are many teachers who are happy to indulge us. But unless we have already developed a really deep understanding and realization of the view of emptiness, as Rinpoche says, we might think we’re practicing Dzogchen but it’s going straight over our heads. We’re probably just practicing shamatha, if that. Indeed, how do we even know if we’re receiving actual Dzogchen teachings in the first place? Does the teacher even have an authentic realization of these teachings and practices? As Rinpoche says, much of so-called Western Dzogchen really is just shamatha.

Similarly in the Vajrayana, a lot of people love to refer to non-duality to justify all kinds of excesses. They say ‘yes, in Vajrayana it’s allowed. You can have meat, alcohol, sex, wealth, whatever you want’. And indeed that is true. There’s nothing about the Madhyamaka view or the Vajrayana view that says those things are bad. But practically, do you really realize that view? Or are you just gratifying your ego desires? As Rinpoche often says, the easiest way to tell is just do the opposite. Try just eating rice and dal for six months. No sex. Live in poverty. Wear the same second-hand clothes everyday. Beg for your food. Can you truly say you have no preferences? Well if so, then maybe you could say you are ready for these tantric practices. But if you still have an ego preference and you’re just giving in to that, and using nonduality and the seeming openness of the Vajrayana path as a justification or excuse to have meat and alcohol and sex and money and all the rest – well, that’s not practicing Dharma. As we saw last week, that’s just spiritual materialism. That’s just using Dharma as an adornment for your ego.

Cultivating renunciation mind [t = 0:32:23]

I know many of us are very busy. It can sometimes seem impossible to do the study or the practice that our Dharma path requires. Traditionally Rinpoche would emphasize renunciation and motivation at the beginning of each teaching, and indeed that’s something several of you have asked for and something we should do. So even though I haven’t explicitly taken the time to remind us of renunciation mind and our bodhicitta aspiration at the beginning of each teaching, I’m hoping the practitioners amongst you are doing it yourselves when we’re starting. As Rinpoche says, it’s important to take time to establish or, as he puts it, to tune our motivation. I really like that idea of tuning – are we off key? Or are we really in tune with the clear intention that all we’re about to study and practice is not just for our selfish or conventional needs, but really it’s for the purposes of liberation of all sentient beings.

When Rinpoche teaches these teachings on emptiness and the Middle Way, typically at the beginning of each session he will chant the Heart Sutra. So if you are not doing that already, then maybe before these webinars or before you study the text, you could chant the Heart Sutra. It’s strongly encouraged. It’s also encouraged, and Rinpoche encourages people to do this as well, to actually write out the Heart Sutra. It’s even better if you can do calligraphy in whatever language you can speak. But just writing it out, chanting it, just engaging with the Heart Sutra is considered very meritorious.

When Rinpoche taught the Madhyamaka in France, every couple of days he would start the session with a long teaching on lojong, on mind training, to remind us about the importance of renunciation and overcoming our worldly ambition and clinging to the eight worldly dogmas. As he explained, it’s traditional as part of these teachings to keep reminding us to not get caught up in our endless worldly pursuits. Because it’s true – If we’re just going to focus on our samsaric goals all the time, we won’t put in the time to study or to practice the teachings on the Middle Way. I’m not going to teach on lojong now, but I would invite you perhaps during the week to spend some time reflecting on the lojong and mind-training teachings, and spend some time reflecting on what is your motivation. How are you spending your week? How much time are you setting aside to really engage in the study and the practice of these teachings? And if you are not making time for Dharma, maybe you could ask yourself what other priorities have become more important in your life. Is that really what you want?

Overview of Week 4 [t = 0:35:03]

Turning now to Week 4, I’d like to give a summary of what we’re going to do. Before I summarize the content, I really want to encourage us to take a mindset of humility this week. A couple of times during the teachings in France, Rinpoche was talking to Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche who cautioned us about refuting the Chittamatra view. He said that we might think we have defeated the Chittamatra, and we might do a victory dance. But as Shantideva says, that is like when a crow meets a dead snake, and the crow dances like a garuda. The garuda is supposedly the most majestic and fearsome of all the birds, and the crow in this case obviously thinks or likes to pretend that it has actually accomplished something. And I think that’s actually a pretty good example, because for any of you who have spent any time with the background reading – and if you haven’t, I strongly encourage it – I suggested several articles to give some background on the Yogachara and the Chittamatra. And if you read these articles, you’ll see several things.

Firstly, it’s not as if there is a single sub-school of the Chittamatra. Their thinking evolved from Asanga and Vasubandhu who founded the school in the 4th and 5th centuries, all the way to Shantarakshita in the 8th century and beyond. So even in India there were many different interpretations of what “Mind-Only” meant. And then, turning to the West – well not just the West, but actually the Indian, Tibetan, and now Western commentators – there is a very wide range of different philosophical interpretations of what the Chittamatra actually meant. And in particular there was a quite a radical shift in interpretration starting in the 1960s. Until that point, Western commentators had primarily seen the Chittamatra as a form of idealism, but since the 1960s it has been seen and engaged with much more as a form of phenomenology. So all this to say that we don’t have a single understanding of who our opponents are, or what they mean to say, or how we should interpret them. So let’s not jump to conclusions that we even understand them, let alone that we have successfully refuted them.

This is another element that Rinpoche talked about, namely arrogance and pride. He said that as we engage in these debates, we may even feel like we’re winning, but we mustn’t start to develop the mindset of “We followers of Madhyamaka are the best” (page 200). Don’t develop that kind of pride, because despising other paths is actually breaking one of the major precepts of the bodhisattva path. But also, by contrast, don’t give up. Don’t think these teachings on emptiness are too difficult. Don’t say ‘I can never do this’, because that’s also ego. That’s just a narrative, a form of ego showing up as resistance.

The problem with secular Buddhists [t = 0:35:03]

There’s a third aspect to how we can get caught in arrogance and wrong views. We shouldn’t think we’re too sophisticated to engage in practice, or that practice is somehow irrational and beneath us. People like to ask, ‘Is Buddhism a philosophy or a religion?’ (page 210). Well, you could argue that question itself is very dualistic. As Rinpoche said, Nagarjuna and the masters of the Madhyamaka tradition say that ‘for someone who accepts emptiness, everything is acceptable’. Even though they see that ultimately all phenomena are beyond extremes, they see no problems in offering flowers and lighting butterlamps. This is just another aspect of applying the Two Truths in our practice and in everyday life.

Here Rinpoche points his criticism towards a lot of contemporary Buddhists, especially the so-called ‘secular Buddhists’. For any of you who’ve read Stephen Batchelor’s Buddhism Without Beliefs, or others among what Rinpoche likes to call the ‘British Buddhists’, you will know that Batchelor likes to present Buddhism as a form of secular rationality. He might perhaps say that he is saving Buddhism from the irrationality and religiosity that has crept into the tradition over the centuries, and returning it to its rational and secular roots in the Pali suttas.

But here we might say that Batchelor is confusing the irrational with the beyond-rational, the nondual. Unlike Nagarjuna and Chandrakirti, he cannot accept religious methods or seemingly religious methods as part of his secular Buddhist path. For example, he tells the story of his personal experience on the Vajrayana path, and how he has come to see the Vajrayana as a form of irrational theism and cult-like guru worship, rather than seeing it as a skilful means that can take us beyond the limits of rationality to realize the nondual. So it would seem that Batchelor definitely does not find everything acceptable in the way that a follower of the Madhyamaka would. So in other words, we can only imagine that Batchelor must have some form of truly existing view which is making certain things unacceptable to him. And because of that, he will become an opponent of Chandrakirti. We’ll return to this in Week 7.

How Chandrakirti refutes the Chittamatra [t =0:39:42]

Now although we can see that the various strands of Chittamatra belief are very complex, and we can’t necessarily identify a single position or single consistent interpretation to engage with, there is one thing which I think is common to most, if not all of the schools. And this will be the basis of Chandrakirti’s refutation. This is the core Chittamatra idea that there is a truly existing mind or consciousness without object – in other words the famous “Mind-Only” that gives the school its name (citta= mind, matra = only). In other words, our opponents say that in their view there is a truly existing subject without a truly existing object:

• Truly existing subject: the perceiving subject is the ‘Mind-Only’ or alayavijñana in Sanskrit (kunzhi namshé in Tibetan), which is the base of all perceptions. It exists substantially as a ‘storehouse consciousness’ and is nevertheless nondual ‘mere clarity, mere awareness’. It is also referred to as the ‘dependent nature’ (zhenwong in Tibetan or paratantra in Sanskrit) (all these terms will be explained in more detail later on);

• Not-truly existing object: the perceived objects are parikalpita (küntak in Tibetan) that are dualistic perceptions, experiences and imputations caused by our mental projections, which in turn are caused by the karmic habits and propensities that we have previously developed, which are stored in the alayavijñana.

As Sonam Thakchoe notes in the article “The Theory of Two Truths in India” that was included in the pre-reading, there was already criticism of the Chittamatra view from the pre-Madhyamaka realist Buddhist schools including the Vaibhashika. They had a number of challenges to the view of a truly existing subject without a truly existing object. First, if there is no truly existing object, what grounds perception in space and time? Second, if there’s no object, why do different people see different things? What gives rise to their different perceptions? Third, if our objects are only imaginary and unreal, how do these imaginary objects give rise to actual results in the world? We’re familiar with the idea that our thoughts lead to real action and results in the world, but how can something that doesn’t exist be causally efficient in this way? We’ll come back to these questions, but you might like to contemplate how you might answer these challenges if you held the Chittamatra view.

Now a lot of what we’ll see in Chandrakirti’s refutation today uses the following reasoning: if the object of perception (the cause) doesn’t truly exist, but the subject that is conscious of that object does truly exist (the result), then we obviously don’t need the object to produce that consciousness. If the cause isn’t real, we don’t need the cause in order to produce the result. The object makes no difference. So why don’t all subjects experience the same things irrespective of their objects? Why wouldn’t a subject without the not-truly existent object perceive the same thing as a subject with the not-truly existent object?

For example, let’s say that a person has a certain dream experience. Maybe they dream of a giant pink elephant. If that elephant doesn’t exist while they’re dreaming, it’s equally non-existing during the daytime, so why don’t we perceive giant pink elephants in the daytime? In order to defend their position, we’ll see that our Chittamatra opponents come up with a variation on the idea of a ‘continuum’ that we saw before (in verse 6:15). This week we’ll talk a lot more about the idea of a ‘potential’ or a ‘seed’, but basically it’s an attempt to solve the same basic problem that we need to explain causality where we have a non-truly existing cause and a truly existing effect. As we saw in Week 3, if our opponents believe in any kind of truly existing arising, their position collapses under analysis.

Where we are in the Hero’s Journey [t = 0:42:11]

As in previous weeks, I’d like to read the relevant verses from the 10 Bulls. I’ll read two verses this week and another two next week.

4. Catching the Bull

I seize him with a terrific struggle.

His great will and power are inexhaustible.

He charges to the high plateau far above the cloud-mists,

Or in an impenetrable ravine he stands.

Comment: He dwelt in the forest a long time, but I caught him today! Infatuation for scenery interferes with his direction. Longing for sweeter grass, he wanders away. His mind still is stubborn and unbridled. If I wish him to submit, I must raise my whip.

5. Taming the Bull

The whip and rope are necessary,

Else he might stray off down some dusty road.

Being well trained, he becomes naturally gentle.

Then, unfettered, he obeys his master.

Comment: When one thought arises, another thought follows. When the first thought springs from enlightenment, all subsequent thoughts are true. Through delusion, one makes everything untrue. Delusion is not caused by objectivity; it is the result of subjectivity. Hold the nose-ring tight and do not allow even a doubt.

So this week we’ll start to get the sense perhaps that we’re starting to master the bull. We’ll be starting to feel a sense of mastering the refutations. And in the Hero’s Journey, we’re now in the very middle of Act II, which is sometimes called “the promise of the premise”, where the premise of our journey starts to bear fruit. In this case, we set out on a search for the truth, and realized that we first need to establish the view. So now we’re starting to get a better sense of what that means in practice. We’re being tested. Our opponents are tough. But we are winning the fights. We’re beginning to become confident that we’ll prevail. We’re starting to have fun. In this case we’re starting to see that truly existing other-arising can be refuted. Our refutations work, and perhaps we’re even starting to understand why.

Some introductory comments on the Chittamatra [t = 0:44:09]

Now turning to the text, let’s start with some introductory comments on the Chittamatra. You’ll see the school is called both Yogachara and Chittamatra, and the names are generally used interchangeably. What do these names mean? Yogachara literally means ‘one whose practice is yoga’. Chittamatra means ‘mind only’, where chitta means ‘mind’ and matra means ‘only’. Historically, this school emerged in India in the 4th/5th centuries, whereas Nagarjuna lived in the 2nd/3rd centuries, so he didn’t refute their views in his Mulamadhyamakakarika, which is one of Chandrakirti’s source texts. This is one of the reasons that Chandrakirti is spending so much time on the Chittamatra as an opponent, because the previous Madhyamaka masters had not really disposed of them fully. Interestingly, our other source text, the Dashabhumika-Sutra, is also a source text for the Chittamatra. So some of the debates will be quite interesting and quite challenging, as some of the refutations will rest on differing interpretations of the source text that we share with our opponents.

Just in passing, I know we said a moment ago that we’re not entirely clear what the Chittamatra believe or whether they believe just one thing. And as I just mentioned, we’re going to make an assumption here that they believe in truly existing other-arising. But it’s not even clear the Chittamatra actually believe that. The Wikipedia entry on ➜Yogachara is very helpful on this point:

As evidenced by Tibetan sources, this school was in protracted dialectic with the Madhyamaka. However, there is disagreement among contemporary Western and traditional Buddhist scholars about the degree to which they were opposed, if at all. To summarize the main difference: while the Madhyamaka held that asserting the existence or non-existence of any ultimately real thing was inappropriate, some exponents of Yogachara asserted that the mind (or in the more sophisticated variations, primordial wisdom) and only the mind is ultimately real. Not all Yogacharins, however, asserted that mind was truly inherently existent. According to some interpretations, Vasubandhu and Asaṅga in particular did not.

The position that Yogachara and Madhyamaka were in dialectic was expounded by Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang) in the 7th century. After a suite of debates with exponents of the Madhyamaka school in India, Xuanzang composed in Sanskrit the no longer extant three-thousand verse treatise The Non-difference of Madhyamaka and Yogachara. Some later Yogachara exponents also synthesized the two views, particularly Shāntarakshita in the 8th century, whose view was later called “Yogachara-Svatantrika-Madhyamaka” by the Tibetan tradition. In his view the Madhyamika position is ultimately true and at the same time the mind-only view is a useful way to relate to conventionalities and progress students more skilfully toward the ultimate.

In other words, the Yogachara-Svatantrika-Madhyamaka accept that in the ultimate truth, all phenomena are beyond the extremes of existence, non-existence, both, or neither. And at the same time in the relative truth, they accept the phenomenological focus of the “Mind Only”. And we’ll see, even more so next week actually, that there’s a lot of overlap between the Chittamatra view and debates in contemporary phenomenology, cognitive science, and philosophy of mind. For example, there is a debate in contemporary philosophy of consciousness around the 3rd person versus the 1st person perspective. For example, is our 1st-person consciousness real or is it empty? And Buddhists like Francisco Varela and Alan Wallace have been debating with western philosophers for many years now at the series of Mind and Life conferences started by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. You’ll hear Western philosophers use terms like ‘qualia’, the ‘Hard Problem of Consciousness’, and so forth. I’ve suggested some pre-reading on this topic for Week 5, and we’re going to dig into this next week when we look at the lack of true existence of the person, and in particular the lack of true existence of subjectivity. Because when we talk about ‘the self of person’, many of us are referring to the immediate 1st-person sense of subjectivity, the ‘here I am’, the Cartesian cogito ergo sum.

Verses 6:45-6:46

On the 6th bhumi, the bodhisattva realizes that phenomena are mind alone [t = 0:48:28] [MAV PDF page 159]

We return to the text at verse 6:45, where the Chittamatra set our their view:

[6:45] Without object, and no subject to be seen,

The three-fold world is fully realised as consciousness alone.

Thus, the Bodhisattva dwells in wisdom,

Realizing mere consciousness as suchness.

They believe that on the sixth bhumi, the bodhisattva realizes that phenomena are mind alone. Like the Madhyamaka, the Chittamatra also believe that the 6th bhumi bodhisattva realizes emptiness, but they would define ’emptiness’ differently from Chandrakirti. Whereas in the Madhyamaka we say phenomena are empty of true nature, the Chittamatra say they are empty of labelling. This might sound similar, but it’s actually very different, because for the Madhyamaka, nothing exists substantially. Whereas for the Chittamatra the base of labeling exists substantially. In verse 46, they offer a very good analogy to explain their view:

[6:46] As wind agitates the sea

Stirring up waves on the water surface,

From the seed of all, so-called all-ground,

Mere consciousness arises through its own potential.

Just as the wind stirs the ocean to make waves, our habits stir the alayavijñana (which is often shortened to alaya), which is what people are referring to when they talk about their ‘consciousness’ in conventional truth. This is the “Mind Only” that gives the Chittamatra school its name, and it is the source of all our dualistic phenomena and experiences. Of course, from the Madhyamaka perspective, the problem with this analogy is that it implies there actually is an ocean there being blown into waves by the wind. Whereas, as Chandrakirti will demonstrate, there is no truly existing alaya even though our opponents would like to believe there is.

Verse 6:47

The definition of “Mind-Only” [t = 0:49:42] [MAV PDF pages 160-162]

In verse 47, the Chittamatra explain their understanding of the Mind Only, which they refer to as the ‘dependent nature’:

[6:47] Therefore the essence of the dependent nature,

Becomes the cause of the imputed existence of phenomena.

Manifesting, with nothing to grasp externally;

Inherently existing, it is not the domain of elaborations about existence.

According to the Chittamatra, all of reality is included within the Three Natures (the definition of all three appears below), and the dependent nature is one of these three. In particular, as verse 47 summarizes, this dependent nature is (1) truly existing, (2) the cause of dualistic phenomena, in the sense that it is the base upon which dualistic phenomena are projected, (3) not itself dualistic (i.e. ‘not the domain of elaborations’). All this will be explained in more detail in just a moment.

The Chittamatra still hold to Two Truths: everything is either phenomena (dharma) or the nature of phenomena, which is ultimate reality (dharmata). So although they have Three Natures, they only have Two Truths like the Madhyamaka. And their theory is representationalist, which means that according to their theory you can’t access phenomena or external objects directly. You can only access their representation. If we compare this to our previous opponents:

• Vaibhashika: they are realists that believe in atoms and moments of thought, but they are not representationalists, because they believe you can have a direct perception of these real objects, these atoms and moments of thought.

• Sautrantika: they also believe in the atoms of matter and of mind. But according to them, you cannot have a direct perception of reality. You can only have access to a representation of reality, something that’s caused by the external objects.

By the way, when we talk about representations, this is very similar to how contemporary neuroscience would describe how we perceive the world. Our naive intuition is that we see visual images of the world directly. We might perhaps imagine that our visual system works a bit like the way that analogue movies are made up of a series of individual images. But what’s actually happening is quite different. Our eyes are taking in a stream of information, and converting it to neural impulses that travel along our optic nerves to our brain. And then our brain reworks and integrates all those neural impulses and constructs a representation that we interpret as a visual image. We’re not seeing the world directly. We’re seeing a ➜representation, a construction. It’s a virtual reality.

To take another example, when we watch a DVD, we see visual images on our television screen or computer monitor. But there are no images stored on the DVD itself. The images are all stored as representations, in this case as a series of “0” or “1” binary digits that comprise the data on the DVD. As with biological visual perception, digital images and movies are representations.

The Sautrantika, an earlier Buddhist school, and the Chittamatra both explain perception in terms of representation. The difference is that for the Sautrantika, the representations are caused by external objects (as in contemporary scientific accounts of perception), whereas for the Chittamatra these representations are caused by the Mind Only, not by anything external. To be more precise, they’re caused by subliminal impressions, vasana (Sanskrit) or bagchak (Tibetan), within the foundational consciousness (the alayavijñana), the nondual base that is the ‘Mind Only’. (Note: In the Madhyamakavatara root text, the bagchak are first introduced in verse 6:56).

How habitual tendencies manifest as dualistic experience [t = 0:52:02]

And what are these these vasana, these bagchak? Wikipedia has a good article on ➜vasana. They are habitual tendencies or dispositions, a word that is often used synonymously with the word bija or seed. Although this term is found in the Pali and the early Sanskrit sources, it really comes to prominence with the Yogachara, because they’re using this term, this idea of the habitual tendency or seed, to denote a latent energy resulting from actions. The idea is that if we engage in certain actions habitually, they are thought to become imprinted in our mindstreams. They actually refer to consciousness, the alayavijñana, as a ‘storehouse consciousness’. It’s almost like a bank account that stores all our karmic traces, like a record of our actions.

And it’s believed that these habitual tendencies predispose us to particular patterns of behaviour in future. They’re like a stain almost, a colouration of our mind stream. For example it’s assumed that if someone smokes, they will be strengthening the habitual tendency for that urge to smoke to keep coming back. The idea is that if we behave in a certain way, it will trigger similar actions in the future, thereby reinforcing these bagchak. Again, this is very similar to contemporary neuroscience, where there is the adage ➜”neurons that fire together wire together”. We know that repeated behaviour tends to solidify our way of thinking and our way of acting, which is part of the reason that practice, including Dharma practice, is effective as a way to change our habits. It’s because we’re literally rewring our brain by intentionally reinforcing our desired new habits.

It’s very similar to an example used by Thich Nhat Hahn, who has lovely language about this. He talks about ‘watering the seeds of sorrow and watering the seeds of joy’, making the point that at any moment in time you can choose which habits of mind to reinforce. Am I going to put energy into watering the seeds of sorrow, the things that make me unhappy? Or am I going to put energy into watering the seeds of joy, the things that will make me happy? Because the more we water the seeds of sorrow, the stronger they become. Likewise the more we water the seeds of joy, the stronger they become. Thich Nhat Hahn’s choice of language fits the Chittamatra view very well, as the Chittamatra theory of bagchak or habitual propensities is also expressed in terms of the bija or seed, the karmic traces that manifest as dualistic phenomenal experience. There’s a similar example in the story that compares our mental and emotional habits to ➜two wolves: there’s a good or noble wolf, and a bad wolf. And the wolf that becomes stronger is the one that we feed the most. These are very similar ideas – where we put our energy, the wolf that we feed, the seeds that we water – that is what becomes strong. So I think actually the Chittamatra idea is very intuitive. It makes a lot of sense and actually fits with contemporary neuroscience, with the idea that habits are real, they’re embodied physically in our brain, and the more we do a certain thing the more we have these tendencies, or what we could call karmic traces.

The Three Natures [t = 0:55:12]

Now we introduce the Three Natures. There are two that are conventional truth and one that is the ultimate truth. So again, we have Two Truths. Briefly, we may understand the Three Natures as follows:

(1) Parakalpita (küntak) or imputed reality

The first of the Three Natures, which is part of conventional truth, is parakalpita (Sanskrit) or küntak (Tibetan). This imputed reality includes all our dualistic experiences and perceptions, all projections and all interpretations that we’re making based on the underlying seeds which are the mental phenomena. As you may recall from previous weeks, the Sanskrit word parakalpita that is here translated as ‘imputed reality’ is the same word that we previously translated as ‘imputed ignorance’ (which is one of the two kind of ignorance, together with ‘innate ignorance’). For the Chittamatra, this imputed reality includes all our imputed dualistic phenomena and experiences, and also things like language, where we’ve come up with a conventionally imputed system.

We think these imputed phenomena are external objects. They appear to us as dualistic objects in the world (3rd person) that are separate from our subjective consciousness (1st person). But according to the Chittamatra, this apparent duality is completely unreal. None of this apparent phenomenal reality truly exists. This is all happening within the Mind Only. It is because of this denial of external reality that the Chittamatra is considered a form of ➜idealism within western philosophy.

(2) Paratantra (zhenwong) or dependent nature

The second nature is called paratantra in Sanskrit or zhenwong in Tibetan. It is also part of conventional truth, and it is the base for all the projections. The Chittamatra have a lovely example to illustrate the relationship between the base and the projections. Let’s imagine there is a striped rope lying on the floor in a poorly lit room. If we open the door, we might mistake this rope for a snake, and then we might quickly close the door again and run away. In this example the striped rope is the base (the equivalent of zhenwong / parantantra) for our idea of snake, which is an incorrect projection or imputed reality (küntak / parakalpita). We think we see a snake, but it is a projection, an imputation. There is no snake there in reality. We are imagining it based on our habitual patterns of thought, as we have learned that striped ropes and snakes look similar in many way. And if we’re afraid of snakes, we’re even more likely to jump to the incorrect assumption that the rope is a snake. The perception of a snake is invalid relative truth, because if other people were to look at that rope, they would not see a snake. They would see a rope. Likewise, if we were to turn on the light in the room, we also would realize that what we thought was a snake is actually just a rope.

As we saw earlier, the zhenwong is actually the alayavijñana, which is like a storehouse that holds our collected karmic propensities and habitual tendencies, the bagchak. Because these habitual tendencies condition the alayavijñana and determine how it manifests, we refer to it as the dependent nature because it is causally conditioned (pratyayādhīnavṛttitvāt). And although it is called ‘Mind Only’, we are not referring to a dualistic mind like our ordinary minds because anything dualistic is a projection, and is included in the first category of parakalpita or küntak. The ‘Mind Only’ that is the zhenwong refers to a nondual consciousness, which the Chittamatra identify as the 8th consciousness. Sometimes we refer to it as ‘mere clarity, mere awareness’. And the Chittamatra explain that it is devoid of duality, but nevertheless it exists substantially and it’s completely beyond words or language or expression. For the Chittamatra, the zhenwong is considered to be conventionally real. As we just saw, the imputed reality or parikalpita is conventionally unreal – we only think it is real because of our confusion, in the same way that we see a snake where there is only a rope. But for the Chittamatra the zhenwong is conventionally real. Now perhaps you might already be thinking, ‘wait a second, this is starting to contradict the cowherd’s perception, because no cowherd would describe conventional truth this way’.

And although the striped rope is a popular example, it’s actually a little bit misleading because the striped rope is already an object, a dualistic phenomenon. Whereas we know the base is nondual. So the striped rope might confuse us when we’re trying to understand the zhenwong. We’ll come to a better example in the next few verses, which is the way that the different beings in the six realms perceive water differently. As Chandrakirti will explain, there is no truly existing base for the various perceptions of the six realms. Nevertheless, humans see ‘it’ as water, fish see ‘it’ as a home, and the hungry ghosts, the pretas, see ‘it’ as pus and blood and excrement. So different beings make completely separate projections onto this supposed base, even though there is no truly existing base at all according to Chandrakirti. But for the Chittamatra, yes there’s a base, but according to them it’s beyond duality. So just to be clear: for all the lower Buddhist schools – the Vaibhasika, the Sautrantika, and the Chittamatra – there is a truly existing base. And that is why we describe their theories as other-arising. According to these other Buddhist schools, our subjective experience is based on – caused by – a truly existing objective base, which is both ‘other’ than our subjective experience and at the same time it is the cause of our subjective experience. Whereas for Chandrakirti, there is no truly existing base, so there is no truly existing other-arising.

(3) Paranispanna (yongdrüp)

The third nature is the ultimate truth. It is called paranispanna or yongdrüp in Tibetan, and it is the ultimate reality. The Chittamatra would say the same thing as the Madhyamaka when describing ultimate truth, namely that the ultimate truth is emptiness, beyond dualistic existence or appearance. But what the Chittamatra mean by this is a little complicated. I’ll read Vasabandhu’s definition of this parinispanna or yongdrüp, which may be found in Sonam Thakchoe’s article “The Theory of the Two Truths in India”. Vasubandhu describes parinispanna as follows:

“The perfect nature (parinispanna) is the eternal nonexistence of ‘as it appears’ of ‘what appears’ because it is unalterable.”

Let’s add some explanatory notes so we can understand this a little better:

“The perfect nature (parinispanna) is the eternal nonexistence [i.e. it’s never truly existing] of ‘as it appears’ [i.e. the küntak or dualistic projections] of ‘what appears’ [i.e. the base, the zhenwong] because it is unalterable.”

This is still a little hard to follow, but what Vasubandhu is saying is that these projections, the küntak, are always non-existent. There’s no such thing as a truly existing projection. Whereas the base, the zhenwong, is unalterable and truly existing. And it is always the case – in other words, it is ultimately true – that the projections are unreal and the base truly exists. That is the ultimate truth.

There’s some more detail which Rinpoche touched on, notably that the zhenwong actually has two aspects. It has a pure and an impure aspect, which actually corresponds to progress along the path. Because in samsara, as we’ve just described, our zhenwong is conditioned by our habitual patterns or bagchak. We have all these seeds or imprints, these dualistic karmic habits which are causing the zhenwong to manifest for us as the confused dualistic phenomenal experiences of samsara. This is impure zhenwong. But if we practice, we can gradually replace the impure seeds with pure seeds, and we’ll change the contents of our storehouse consciousness. We will change our bagchak, the habitual patterns that are actually stored in our alayavijñana, and we’ll gradually purify our zhenwong. The Chittamatra idea of the path is that it involves the purification of the zhenwong. It involves replacing the bad seeds with the good seeds, replacing the seeds of sorrow with the seeds of joy.

Challenging the Chittamatra [t = 1:02:37]

Now that we have set out the Chittamatra view, it is time for refutation. The Madhyamakavatara doesn’t actually say much about the early Buddhist schools, but some of the pre-reading touches on this, and I think it’s quite helpful to understand their challenges to the Chittamatra, as it will help us understand Chandrakirti’s approach to refuting them. As we saw previously, the early Buddhist schools challenge the Chittamatra with three questions:

[Q]: First, you’ve got no object how do you ground your perception in space and time?

[A]: Here the Chittamatra answer with the example of the dream. They say that in a dream, the person you meet in your dream appears at a specific place and time in the dream. The perception is therefore grounded in space and time, even though the object doesn’t truly exist.

[Q]: Second, why do different people see different things?

[A]: Here the Chittamatra answer using a common Buddhist example. As we said earlier, according to the traditional Buddhist understanding of the six realms, beings in the different realms have very different experiences and perceptions. For example, water appears very differently to different beings in the different realms. Humans see water as something to drink, fish see a home, and the pretas see pus and blood and excrement. And this inter-subjective agreement among beings within each of the six realms is due to the maturation of their collective karma. Here the Chittamatra say, ‘Buddhists accept this conventionally, so why would you argue with us?’

[Q]: Third, how can we have a causally efficient object that is nevertheless not truly existing?

[A]: Here the Chittamatra bring the example of a wet dream. Even without sex, you can still have the emission of semen because of a dream fantasy while you were asleep. So you can have a real effect, even if the cause is not real.

As we can see, the Chittamatra are able to defend themselves against the challenges from the early Buddhist realist schools, but Chandrakirti’s line of refutation is different. Chandrakirti does not accept the idea that you can have a truly existing subject or consciousness without a truly existing object, and so he presses the Chittamatra to give him an example. And so our opponents will now offer four different examples, and they’re all actually good Buddhist examples. But it turns out that none of them actually works as an example of a truly existing subject without a truly existing object. And by the way, the examples would all work perfectly if the Chittamatra did not insist that the alayavijñana truly exists, but because they insist the alaya truly exists, it means they’re insisting on truly existing arising, and that’s what makes their theory of causality fall apart.

The four examples or analogies that the Chittamatra offer are:

• (verse 6:48): deluded mental consciousness – the example of the dream.

• (verse 6:54): deluded sense consciousness – this is our old friend the eye disease, where the afflicted person sees falling hairs where there are none in reality.

• (verse 6:69): mistaken meditation – this is the classic Theravada meditation known as the the corpse meditation or the skeleton meditation.

• (verse 6:71): deluded perception – this is the example that we’ve already discussed, where there are different perceptions for sentient beings in the different six realms.

Verses 6:48-6:49

Analogy #1: Deluded mental consciousness (dream) [t = 1:05:12] [MAV PDF pages 162-163]

Chandrakirti would like an example of a truly existing mind without a truly existing object. And in verse 48, the Chittamatra offer their first example, the dream:

[6:48] Is there an example of an [intrinsic] mind without an object?

You say: “As in a dream”, but when I look

At my mind when it is dreaming,

It has no [intrinsic] existence. Hence, you have no valid example.

The dream is an example of a truly existing mind, because we are subjectively aware now that we were also subjectively aware during the dream, and the dream object didn’t exist. But Chandrakirti is not happy with this. He says, well what makes you say that the dream object is not truly existing, but the dream subject is truly existing? You have given no evidence for this. Why wouldn’t you say that the dream subject is not truly existing in just the same way that you say the dream object is not truly existing? You still haven’t given any evidence for your assertion that there is a truly existing subject without a truly existing object.

Chandrakirti continues cross-examining his Chittamatra opponents in verse 49:

[6:49] If there is memory of the dream when awakening,

And that mind exists, then the external objects [of the dream] should exist in the same way,

Because remembering [the dream], you may think, “I saw”.

In the same way, the external world [of the dream] should also exist [when awake]

He says you claim that the waking subject, the mind that remembers the dream, is a truly existing mind. You also maintain the dream doesn’t truly exist. Yet when I ask about your dream, you can remember your dream and you tell me what you saw in the dream (the ‘external objects’). You are using these ‘external objects’ to confirm the identity of your dream (for example, that you dreamed of giant pink elephant rather than a giant green elephant – after all, if we can’t be sure that the waking memory of the dream is about the same object as the dream itself, then how do we know the whole thing isn’t simply an hallucination you’re making up right now?) But that sounds like you’re saying that the external objects in your waking memory of the dream truly exist. How could they serve as evidence for anything if they’re unreal? But in that case, why aren’t the external objects of the dream world likewise truly existent?

As far as Chandrakirti is concerned, when someone is awake, both their subjective mind and their objective perception are conventionally accepted as real. But when someone is talking about their dreams, the dream mind and the dream object are both conventionally unreal.

Verses 6:50-6:53

Refuting that it exists because it is a dream [t = 1:06:15] [MAV PDF pages 163-165]

In verse 50, the Chittamatra talk about how three things function together to cause a perception to appear in subjective awareness. These three are: (1) the external objects of perception, (2) the eye consciousness, and (3) the result, the mental representation of the external objects that appears to subjective consciousness (i.e. “mind consciousness”):

[6:50] While sleeping there is no eye consciousness,

In the absence of [external objects], there is only mind consciousness

Whose manifestations are grasped as external.

As in the dream, so it is [when awake].

For Chandrakirti, all three are equally not truly existing. For the Chittamatra the first two, the external object and the eye consciousness, are not truly existing. The Chittamatra believe that all dualistic appearances (küntak) manifest as projections that are based on the zhenwong. This includes not just projections of external objects, but projections of physical organs such as an eye consciousness. For them, the only thing that truly exists is the mind that perceives these projections, the nondual zhenwong or alayavijñana. This is equally the case while sleeping as while awake.

Chandrakirti cannot accept that, and in the next few verses (from 6:51 to 6:53), he’s basically saying that there cannot be a truly existing subject with no truly existing object. In verse 51 he says that if you say the object and the eye consciousness do not exist, then how can these non-existent causes give rise to a result that is real, this mental representation that appears to the truly existing subjective consciousness? This makes no sense.

[6:51] However, just as external phenomena in your dreams are unborn

Likewise, mind too is unborn.

The eye, its object, and the mind they create-

All three are false.

[6:52a] These three are also false in regard to hearing and so forth.

As Rinpoche says, the verses themselves are actually very simple, because really all that Chandrakirti is doing is challenging the idea that you could have a real subject and an unreal object functioning together in a subject-object relationship. Because as far as he’s concerned, you could either have both subject and object as real, or both as unreal, but the idea of having one real and one unreal makes no sense. Here we might go back to our example of the marble representing something that is truly existent, interacting with a cloud representing something that is not truly existent. If you visualise these two together, you can immediately see that it doesn’t work. A marble can hit a marble, or you can imagine two clouds merging together. But a marble and a cloud? How does that work? It doesn’t make sense. In verse 52, Chandrakirti says just as there is no truth in the cognition of the dream object, there’s equally no truth in the cognition of the waking object. There’s no truly existing mental representation there either, no truly existing consciousness.

[6:52bcd] As in dreams, so also in this waking state

Their phenomena are false – there is no mind,

No objects, and no sense-faculties.

In verse 53, Chandrakirti says the object, the eye consciousness and the mind, are all similarly not truly existing. Whereas as we’ve seen, the Chittamatra say the mind truly exists but not the senses and not the objects:

[6:53] In ordinary experience, just as while awake,

While sleeping, these [above] three seem to exist;

Once awake they do not.

Awakening from the sleep of ignorance is similar.

The Chittamatra might claim they have a nondual theory, but for Chandrakirti it is extremely dualistic. They have a dualistic distinction between a truly existing subject and a non-truly existing object. This challenge is very similar to a lot of the contemporary cognitive science debates about the 1st and 3rd person. We’ll come back to this next week, and we’ll see that the debates in contemporary philosophy of consciousness are actually quite similar to the debates between Chandrakirti and the Chittamatra. For example, what is the status that we’re ascribing to the subject, our consciousness? Does it truly exist, or is consciousness just an illusion?

Verses 6:54-6:55

Analogy #2: Deluded sense consciousness (eye disease) [t = 1:09:25] [MAV PDF pages 165-170]

Now on verse 54 we move to the second example of deluded sense consciousness. This is an example we have seen before, of a specific eye disease that results in a person seeing falling hair where there is none:

[6:54] The consciousness of someone with diseased eyesight,

And the floating hairs that appear due to that disease [do exist as non-external phenomena].

These both are true for that mind,

But for the clear-seeing both are false.

For Chandrakirti this is easy to refute. He says either you have the eye disease, in which case you both have the object (the falling hair) and you have the mental representation (the subjective experience of seeing falling hair). Or you have no eye disease, in which case neither subject or object exists. So again, the opponent still hasn’t managed to come up with an example where we have a truly existing subject without a truly existing object.