Alex Li Trisoglio

Madhyamakavatara Week 8: Applying the View in Life

Week 8: Applying the View in Life: Post-Meditation & Everyday Life

26 July 2017 / 142 minutes

Question: How might we apply the view in post-meditation and in our everyday life (e.g. in relationships, at work, etc.)

Reference: n/a

Transcript / Pre-reading / Audio / Video

Introduction [t = 0:00:06]

Good evening everyone, I’m Alex Trisoglio and I’d like to welcome you to Week 8, the last week of Introduction to the Middle Way. Before we start, I’d like to invite us all to just take a moment to set our intention, our aspiration. This week we are going to be talking about how everything we do in life is practice. And listening to teachings is also practice. So just take a moment to set the intention that you will listen to these teachings for the sake of enlightening all sentient beings. Think about what that means for you in terms of how you would like to listen to the teachings.

[10 seconds]

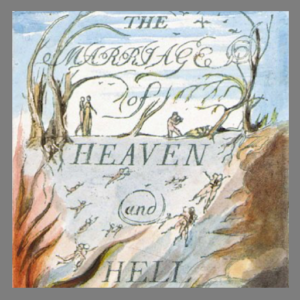

Last week we completed Chandrakirti’s text, the Madhyamakavatara. We spent quite some time on Chapter 11, with its description of enlightenment and the qualities of the Buddha. In particular, we talked about how Chandrakirti emphasizes their inconceivability, which is what you would expect. He is describing non-duality, and we know that we cannot reduce or express the non-dual in concepts and language. At best, we might have a finger pointing towards the moon.

We also talked about applying the view of non-duality in our meditation practice. We talked about how this means changing our subject, our projections. We talked about cultivating equality, equanimity, and preferencelessness, for example in the way that we want to ensure that we treat others in the same way, no matter if they are friend or enemy. We talked about learning to take accountability for our projections, as in Chapter 6 from Shantideva’s Bodhicharyavatara, the chapter on Patience, where he describes how in working with anger he changed his stance from seeing the other person as the aggressor to seeing himself as the one contributing to the other person’s suffering . It’s this kind of radical transformation that emptiness enables. We also talked about compassion as a practical path to approach non-duality which, as we said, is inconceivable. Non-duality is too abstract, so it’s very hard for us to figure out what it means to ‘practice emptiness’ directly. But one of the wonderful things about the Buddhist path is that we have a complete gradual path based on bodhicitta, based on the paramitas, that helps us to get there. I’d like to build on these ideas this week, especially the emphasis on compassion and how we can use our everyday lives as part of our practice.

In the world [t = 0:03:17]

10. In the World

Barefooted and naked of breast, I mingle with the people of the world.

My clothes are ragged and dust-laden, and I am ever blissful.

I use no magic to extend my life;

Now, before me, the dead trees become alive.

Comment: Inside my gate, a thousand sages do not know me. The beauty of my garden is invisible. Why should one search for the footprints of the patriarchs? I go to the market place with my wine bottle and return home with my staff. I visit the wine shop and the market, and everyone I look upon becomes enlightened.

I personally love this verse. The idea here of mingling with the people of the world and ‘everyone I look upon becomes enlightened’ – this is very much about what we touched upon last week: How does the bodhisattva benefit sentient beings? This 10th bull describes the non-dual bodhisattva out in the world, benefiting spontaneously and without dualistic intention. And this is another great thing that Buddhism offers us, because we have the example of the sage, of the dzogchen yogi, as an example of non-duality in practice. We might think of these as mere stories, something poetic or mythical perhaps, but I really want to encourage you to see them as actual role models. As we saw last week, having role models is critical in any journey of change, and one of the wonderful things here is that we actually have role models.

We’re going to spend quite a lot of time this week exploring what it means to act in this kind of non-dual way. As we said last week, the challenge is that we don’t know how to behave like that right away. We don’t know what it means to practice non-duality. So we need some kind of gradual path of practice. So I’d like to talk this week about both the non-dual way of being in the world, and the gradual path of practice in the world that can lead us to non-duality.

Once again we’re going to talk about the Two Truths, but this time not at an intellectual level. Instead we’ll talk about what they mean in practice, and in particular we’ll look at emptiness in the classic Shravakayana and Mahayana paths of practice – the Eightfold Path and the Six Paramitas. We’ll look at those both from the perspective of a gradual path and from the perspective of the non-dual path. Along the way I’ll offer various quotes from Buddhist and non-Buddhist sources, again with the aspiration of giving us alternative ways of understanding and accessing these teachings, knowing that the path teachings resonate differently with each of us.

Hero’s Journey [t = 0:06:36]

We are at the final stage of the Hero’s Journey. We are now in Act III, which is all about bringing our gift or our boon back into the world. In this case, the gift is the view of emptiness. When we learn about generosity in the paramitas, we know that it includes material generosity and protection from fear, but the highest form of generosity is to teach the Dharma, to offer the truth. So it’s actually very appropriate that what we are going to give as our highest gift is our realization of emptiness.

We mentioned previously that Joseph Campbell has a 17-stage model of the Hero’s Journey, and now we come to the last three stages of the journey:

(#15) The Crossing of the Return Threshold: The trick in returning is to retain the wisdom gained on the quest, to integrate that wisdom into a human life, and then maybe figure out how to share the wisdom with the rest of the world.

That’s exactly what we are trying to do this week: how are we going to integrate this wisdom? And how are we going to share it through the course of our engagement with our world?

(#16) Master of Two Worlds: This step is usually represented by a transcendental hero like Jesus or Gautama Buddha. For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance between the material and spiritual. The person has become comfortable and competent in both the inner and outer worlds.

Actually here I wouldn’t use the word ‘balance’; I prefer the word ‘synthesis’, because we’re going beyond trying to find a middle point of balance between two opposites. With the Middle Way, we’re going beyond all opposites and dualistic extremes. We’re going beyond samsara and beyond nirvana. We’re trying to synthesize and not be trapped in either pole: not remaining in nirvana, and not abandoning samsara.

(#17) Freedom to Live: Mastery leads to freedom from the fear of death, which in turn is the freedom to live. This is sometimes referred to as living in the moment, neither anticipating the future nor regretting the past.

Although Campbell is coming from a very different perspective and background than the Middle Way teachings, he’s ending up in a place where the language sounds very similar. And on the topic of giving our gift and sharing it with the world, I’d like to quote the author Toni Morrison:

I tell my students, “When you get these jobs that you have been so brilliantly trained for, just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else. This is not just a grab-bag candy game.”

Self-transformation and self-transcendence [t = 0:09:50]

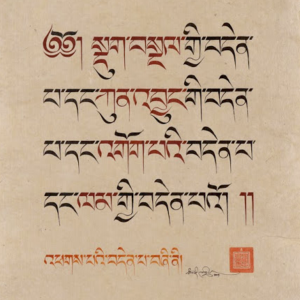

Now we return once again to the Two Truths. We already saw at the end of Chapter 6, in verse 6:226, that the king of swans flies on the two wings of ultimate and relative truth, wisdom and compassion. And we also heard the words of Guru Rinpoche Padmasambhava:

Though my view is as spacious as the sky,

My actions and respect for cause and effect are as fine as grains of flour

This is very much talking about emptiness in the world, which is all about our actions and our respect for cause and effect. We know that view without practice, without action, is just an intellectual understanding. It won’t transform our meditation. It won’t transform our action in the world. As Rinpoche says, 98% of the path is practice. This week we are not talking about practice simply in the sense of sitting on your meditation cushion, but how you are bringing your practice into the world. How are you using the rest of your day to practice, and to embody and realize this non-dual view? Your actions, your respect for cause and effect are just as important here. But the opposite is also true. If we are just paying attention to cause and effect in samsara, we are just ordinary worldly sentient beings, just trying to make sense of the world, make things work in the world, chasing after worldly happiness and success and not actually practicing the Dharma.

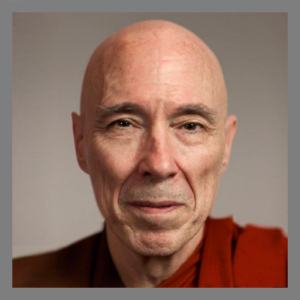

Until now we have talked about the Two Truths intellectually. We’ve used language like ‘ultimate truth’ and ‘conventional truth’, but for most of us it’s very confusing. We don’t really know what it means. We don’t really know what to do with it. Having said that, it is a central idea in these teachings, so I’d like to explore some more practical ways of talking about it. First I’d like to introduce you to a wonderful article called “Self Transformation” by Bhikkhu Bodhi, which is in the pre-reading. He distinguishes between what he calls ‘self-transformation’ from ‘self-transcendence’, and as you’ll see this does actually correspond to the Two Truths, and to wisdom and compassion:

[Self-transformation]: This desire for a transformed personality, for the emergence of a new man from the ashes of the old, is one of the perennial lures of the human heart. From ancient times it has been a potent wellspring of the spiritual quest, and even in the secular, life-affirming culture of our own cosmopolitan age this longing has not totally disappeared. […] Where previously this urge sought fulfilment in the temple, ashram and monastery, it now resorts to new venues: the office of the psychoanalyst, the weekend workshop, the panoply of newly spawned therapies and cults. However, despite the change of scene and conceptual framework, the basic pattern remains the same. Disgruntled with the ruts of our ingrained habits, we long to exchange all that is dense and constrictive in our personalities for a new, lighter, freer mode of being.

Self-transformation is also a fundamental goal of the Buddha’s teaching, an essential part of his program for liberation from suffering. The Dhamma was never intended for those who are already perfect saints. It is addressed to fallible human beings beset with all the shortcomings typical of unpolished human nature: conduct that is fickle and impulsive, minds that are tainted by greed, anger and selfishness, views that are distorted and habits that lead to harm for oneself and others. The purpose of the teaching is to transform such people — ourselves — into “accomplished ones”: into those whose every action is pure, whose minds are calm and composed, whose wisdom has fathomed the deepest truths and whose conduct is always marked by a compassionate concern for others and for the welfare of the world.

[Self-transcendence]: What distinguishes the Buddha’s program for self-transformation from the multitude of other systems proposing a similar end is the contribution made by another principle with which it is invariably conjoined. This is the principle of self-transcendence, the endeavour to relinquish all attempts to establish a sense of solid personal identity. In the Buddhist training the aim of transforming the personality must be complemented by a parallel effort to overcome all identification with the elements that constitute our phenomenal being. The teaching of anatta or not-self is not so much a philosophical thesis calling for intellectual assent as a prescription for self-transcendence. It maintains that our ongoing attempt to establish a sense of identity by taking our personalities to be “I” and “mine” is in actuality a project born out of clinging, a project that at the same time lies at the root of our suffering. If, therefore, we seek to be free from suffering, we cannot stop with the transformation of the personality into some sublime and elevated mode as the final goal. What is needed, rather, is a transformation that brings about the removal of clinging, and with it, the removal of all tendencies to self-affirmation.

It is important to stress this transcendent aspect of the Dhamma because, in our own time when “immanent” secular values are ascendant, the temptation is great to let this aspect drop out of sight. If we assume that the worth of a practice consists solely in its ability to yield concrete this-worldly results, we may incline to view the Dhamma simply as a means of refining and healing the divided personality, leading in the end to a renewed affirmation of our mundane selves and our situation in the world.

In the proper practice of the Dhamma both principles, that of self-transformation and that of self-transcendence, are equally crucial. The principle of self-transformation alone is blind, leading at best to an ennobled personality but not to a liberated one. The principle of self-transcendence alone is barren, leading to a cold ascetic withdrawal devoid of the potential for enlightenment.

I love this: it is very beautiful language around the Two Truths. And as Bhikkhu Bodhi says, if you have no wisdom, it means you’re blind; if you have no compassion, it means you’re barren. We need both, just like the king of swans flies on two wings. I also love the way he uses everyday language like ‘self-transformation’ and ‘self-transcendence’, and for many of us this is much more straightforward and easy to relate to than ‘ultimate truth’ and ’conventional truth’. Next, he talks about what this means for the path:

Of the two principles, that of self-transcendence claims primacy both at the beginning of the path and at the end. For it is this principle that gives direction to the process of self-transformation, revealing the goal toward which a transformation of the personality should lead and the nature of the changes required to bring the goal within our reach. However, the Buddhist path is not a perpendicular ascent to be scaled with picks, ropes and studded boots, but a step-by-step training which unfolds in a natural progression. Thus the abrupt challenge of self-transcendence — the relinquishing of all points of attachment — is met and mastered by the gradual process of self-transformation. By moral discipline, mental purification and the development of insight, we advance by stages from our original condition of bondage to the domain of untrammelled freedom.

Bhikkhu Bodhi’s language of self-transformation and self-transcendence is an alternative way of talking about the Two Truths that can help us to ground Chandrakirti’s wisdom in our lives, and it offers important insights for our practice and post-meditation.

Elegance and outrageousness [t = 0:18:06]

Another completely different approach to the Two Truths may be found in Rinpoche’s wonderful teaching on ‘elegance and outrageousness’, which is from a teaching on the Bodhicharyavatara that he gave in Berlin in 1990:

Outrageousness: Many people think that outrageousness means being free, being able to express one’s own emotions. They cry, they shout and scream … [people think] outrageousness is connected with having a confident personality, like if you dye your hair and cut it in a different style and walk in the street in a very funny dress people, then think it is very outrageous. But that is not outrageousness. It becomes like another era of punk and yuppies. Anyway, to make a more precise definition, outrageousness means ‘to do things genuinely and not to be the slave of society’. Wearing a tie is not so important for being very elegant, but society has determined that elegant people should wear ties, and we have become slaves of that. We have to buy a tie and we have to learn how to wear it properly. We understand the difference between good and bad manners. Even in Dharma practice, outrageousness is so important. It is almost like the display of bravery and courage.

We will talk about this more later. In the teaching, Rinpoche goes on to talk about how outrageousness applies even in our practice – how we make offerings, how we visualize the deity, and so on. Normally we come to our practice with such a poverty mentality. Rinpoche really encourages us not to be limited, but to go beyond our narrow cultural confines and really to try to think in a more expansive, non-dual way. That is outrageousness: doing things genuinely, not being the slave of whatever tribe or group or society we might be part of.

Elegance: You may think elegance is contradictory to outrageousness. A practitioner also has to be elegant. The way he walks, the way he sits, the way he dresses, the way he flips the pages of his sadhana, the way he beads the mala, the way he does meditation. Elegance is so important. In order to be elegant, you may have to wear that tie which we rejected earlier. The idea of elegance is to create the atmosphere. In everything, in Dharma practice and in life, atmosphere is so important. If you create the atmosphere nicely, then the Dharma practice also becomes nice. It’s like when you go to a very special occasion and everyone is wearing nice dresses. That does not mean that your mind becomes sharper, but somehow because of the atmosphere it helps. But when you go to Dharma centres and you’re wearing a floppy dress and you sit on a floppy cushion, we could say the situation is very relaxed – but we could also say it is very clumsy. So your concentration and everything else becomes very clumsy. Elegance is not simply what you wear, but the way that you are, even at home when nobody is watching you.

So outrageousness is going beyond the relative and towards the non-dual, towards the ultimate, whereas elegance is all about working within the conventional. In the 1990 Berlin teaching, Rinpoche extends this distinction beyond practice and into post-meditation and everyday life. Elegance is learning to work with conventional truth, with the language and the norms of society. ‘When in Rome, do as the Romans do’. Elegance means learning to empathize and connect and speak the language of our colleagues and our opponents, so we can build relationships and work together and get things done in the world. Likewise with our practice, elegance means not superimposing our own habitual assumptions and ideas, but approaching situations with a genuine humility and openness, a desire to tame and adapt ourselves to the situation.

Action matters [t = 0:22:12]

All this is to say that action really matters. It matters, as Guru Rinpoche said, to do everything with care, as fine as grains of flour. To do whatever we do with excellence. We talked in previous weeks about the connection between early Dharma and the Greek philosophy, and this idea of ‘excellence’ is very much related to Aristotle and arête (ἀρετή), which means ‘excellence of any kind’, including moral virtue. In its early appearance in Greek philosophy, it meant the fulfilment of purpose or function – the idea of living up to one’s full potential. We develop this moral virtue or disposition to act with excellence partly as a result of our upbringing, and partly as a result of our habits and our practice. Aristotle argues in the Nicomachean Ethics that character arises from habit – it’s a skill that is acquired through practice, just like learning a musical instrument. And so our everyday practices – what we do in the world and in our day-to-day interactions – are critical, as they the places where we strengthen old habits or create new habits, and this is what becomes our character.

The idea of arête has an interesting connection to an older idea in India, the Vedic concept of rta (Sanskrit: ऋतम् ṛtam), which has a very similar root linguistically. Rta has the meaning of ‘that which is properly or excellently joined; order, rule, truth’. It is the principle of natural order which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it. Later, as post-Vedic thought came to India, it became linked to how we uphold the order of the universe (which is dharma), and then the actions of individuals in relation to those practices (which is karma) and those eventually eclipsed rta in terms of their importance. But many scholars say this idea of rta is one of the most important religious conceptions of the Rig Veda. Indeed you could say that it is the beginning of the history of the Hindu religion.

Rinpoche himself talks about our practice in conventional truth very much in terms of karma and action, in terms of accumulating merit and good karma. Yes, we can think about this in some magical way, in terms of some beyond-worldly storehouse of merit, but we can also think about it more practically in terms of purifying our defilements and getting closer to the view of non-duality.

Outrageousness and self-authorship [t = 0:25:12]

Outrageousness can also be understood as learning to define ourselves or to author ourselves authentically, without reference to the norms of society, or our tribe or social network. It does not mean being a rebel. It doesn’t mean being against society, because being against society is still being in reference to society. It’s going beyond either pro or anti. And it’s not just about going beyond the references of society as a whole. It’s about going beyond the references of any of our tribes – our family, our in-laws, our friends, our work colleagues, our sangha, our political party, whatever.

And this is something we’ve come across before, in the work of Robert Kegan from Harvard. In his work on self-authorship, he talks about the process of how we internalize a view in a way that is very similar to the process of view/meditation/action in the Dharma:

• [reliance on external authority] We start with what Kegan calls a ‘socialized self’, which is much like Rinpoche’s explanation that we are ‘slaves to conventional views’. We rely on external rules. We rely on what external authorities – our tribe, our elders, our parents, our society, our sangha and so on – tell us to do.

• [conflict] At some point we reach stage two, and some kind of conflict emerges. Either we see different external authorities in conflict with each other, or we start to see that our internal values are evolving and we can’t make sense of them in terms of external rules. The demands of our external sources of authority no longer fit. So then we have to figure out how to deal with those conflicts.

• [self-authorship] Then finally at stage three we get to self-authorship. This is where we go beyond external sources of reference and instead develop an internalized source of reference. We define for ourselves what is our value system, what is our view, what is the Espoused Theory that we choose as the basis for our lives.

As we saw in Week 1, this idea of a self-authored approach is also very important when it comes to understanding the teachings of Middle Way and establishing our own view of emptiness – the Espoused Theory that will be the basis for our practice. It is vital that we have our own understanding in order that we can apply the view of the Middle Way in post-meditation – in other words, so that when we are out ‘in the world’ and life situations come up, we know how to handle them. Because we can’t always send an email to our teacher to ask for advice. We need to know what to do in the moment, as situations arise. And that’s only going to be possible if the view of the Middle Way has become internalized as part of our Theory-in-Use.

And that’s only going to happen if we develop our own self-authored view of that world that integrates and incorporates the view of the Middle Way. In other words, we need to build the view of the Middle Way into our own ideas, our own models, our own maps, and our own view to ensure that we can apply the correct Dharma to our life situations. In ensuring that our Dharma practice is authentic, yet again view is so critical.

Putting this all together, we come to a much richer understanding of the Two Truths:

• Ultimate truth: corresponds to self-transcendence in Bhikkhu Bodhi’s words, it’s emptiness, it’s wisdom, it’s ultimate bodhicitta, and in Rinpoche’s words it is outrageousness.

• Conventional truth: corresponds to self-transformation in Bhikkhu Bodhi’s words, it’s purification of defilements and cultivation of compassion and skillful means, it’s relative bodhicitta, and in Rinpoche’s words it is elegance.

As we have said many times, we need both of the Two Truths. If we just aim for self-transformation and elegance without self-transcendence, then it’s just worldly self-help and personal development, there is nothing of the Dharma path there. But if we just attempt self-transcendence without the self-transformation, it’s like trying to scale the cliff without really having the equipment. We’ll end up fooling ourselves, we’ll end up with spiritual materialism, ego, building our castles on a foundation of sand. And a high risk of falling into nihilism. Just as we need both of the Two Truths when we establish the view, we also need both of the Two Truths in our practice. We need ultimate and relative, we need self-transformation and self-transcendence. We need elegance and outrageousness.

Spiritual bypassing [t = 0:29:17]

This topic of trying to go too far too fast is really important, because this week we are talking about how to practice emptiness and the path of the Middle Way in the world, in our everyday lives. And there’s some lovely recent work that has been done on a topic that people call ‘spiritual bypassing’, which is about what can happen if you don’t deal with the stuff of the conventional world, of your conventional life and your conventional habits. Bo Heimann talks about this in a piece called “Rethinking Mindfulness” in Levekunst:

There’s another challenge that could emerge from meditation without a solid ground. It can, simply put, contribute to self-deception. Excessive detachment-ability. Blind focus on positive thinking. Fear of anger. Artificial kindness. Neglect of own feelings. Difficulty in setting limits. An intellectual intelligence that is far ahead of the emotional and moral intelligences. Focus on the absolute rather than the relative and personal. Is there a bell ringing? Yes, the above is found in quite a few of us. And, I’m afraid, it is quite common in meditation circles.

The term spiritual bypassing was originally coined by psycho-spiritual teacher John Welwood. Robert Masters has in his book of the same name, evolved the concept. He notes soberly that the road away from life’s pain often ends up in a certain form of bypassing-spirituality that keeps us in pain. Quite a few meditators see no need for important psychological work. They want to enjoy the mountaintop view by being hoisted up by a helicopter. […] We end up being unreliable and vulnerable because the view is not deserved and supported from the inside-out, but purchased. We simply have to climb all the way up if we really want to be free, he points out.

There are no shortcuts. […] We tend to seek and love the big breakthrough and the view from the top of the mountain, but not the small steps and the tough psycho-therapeutic work that’s needed to get up there without a helicopter. [And we expect] this journey should of course be almost painless. In this way, the illusory idea of a shortcut ends up a detour, or perhaps even as a cul-de-sac. Unfortunately, the easy shortcut is sold by spiritual second-hand car dealers. And unfortunately we are up for grabs for empty calories, because we would like to believe that we can do it all in half the time.

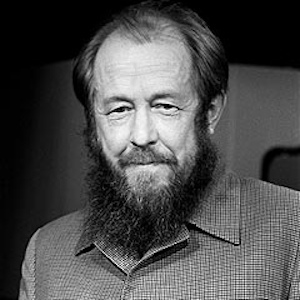

Yes, there’s an important truth here in the idea that we are unwilling to look inside, and instead we just think that we can go outside. In 1973, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn made this point beautifully in The Gulag Archipelago:

If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

We will talk about this more, but let’s summarize some points about the relationship between view and practice:

• Realizing the view through our practice: As Rinpoche said, for some our view leads to our practice, although that is very hard. For more of us, our practice is going to lead to our view. In other words we are going to understand and realize the view of non-duality through our practice, not necessarily prior to our practice.

• Outwardly Shravakayana, inwardly Mahayana, secretly Vajrayana: In terms of balancing outrageousness and elegance, Rinpoche has a lovely saying: ‘We should aim to be outwardly Shravakayana, inwardly Mahayana, and secretly Vajrayana’. In other words, outwardly we should be elegant. We should fit in beautifully – and of course elegance in a fine restaurant means something different from elegance when watching a football match. Inwardly we should have this sense of non-duality and emptiness, this outrageousness, this willingness to step outside habit and convention, always in an elegant way. And then secretly, we should have pure perception, which we will come to later.

• Going beyond meditation and post-meditation: Finally as we said last week, our aim is for the distinction between meditation and post-meditation to collapse entirely.

Why post-meditation as practice? [t = 0:33:34]

We talked last week of meditation practice, and now this week we come to post-meditation. Why should we also use that as our practice? There are several reasons.

1) Not fooling oneself: It’s much easier to fool yourself about your practice and how well you are doing when you are sitting alone on your cushion. But when you are talking to or working with other people, when you are trying to be in a romantic or family or professional relationship, all of a sudden the gaps between your theory and your practice become very clear.

2) Cleaning the window: Secondly, as Bhikkhu Bodhi said, self-transcendence is important at the beginning and the end of the path. But in the middle, a lot of the hard work is self-transformation. It is the work of cleaning the dirt from your window. Nothing glamorous. But that’s exactly what we get to do in our ordinary lives.

3) Time: If you think about it, 30 minutes on the cushion means 23½ hours of the day when you’re not on the cushion. Now I know that many of you are following a two hour a day practice commitment, and some of you even more than that. But even that still leaves more than 90% of your day where you are not practicing! Our lives are short. As the teachings say, this is a precious human rebirth, where we have met the Dharma. We have the opportunity to practice. Surely we want to use as much of each 24-hour period as we can? If you are practicing full time, like 8-10 hours/day, as you might do in retreat, you can get to your 10,000 hours in three years. Hence the classic three-year retreat in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. But it isn’t just a matter of arithmetic. If you are only practicing 30 minutes a day, then to get to 10,000 hours, which is the benchmark for mastery or really internalizing the practice, it is going to take you 55 years. Many of us may not have that long. So we are going to need to use more than just those 30 minutes a day. We are going to want to use as much of the remaining 24 hours as possible as part of our practice.

4) Benefiting others: It’s not just that the 10,000 hours can seem like a long way away, but also every day we are meeting with a lot of people, we are engaging with others in the world. The sooner we can transform our own hearts and minds, the more we can ensure that we are benefiting the people that we meet. And that is our aim as bodhisattvas.

Rinpoche told a lovely story about someone who actually attended one of his three-year retreats, and worked for five years doing a minimum wage job just to save for the flight and the accommodation to be able to participate in the retreat. Rinpoche said that this practice of working at a minimum wage job was creating just as much merit as anything that person did during the retreat itself. I think we should really remember this story, because some of us have the really dualistic idea that we’re only accumulating merit when we are on our cushions. But that’s absolutely not the case – everything we do in our day-to-day lives is just as much an opportunity to accumulate merit, to purify our defilements, to increase our understanding and realization of the view.

Madhyamaka ethics [t = 0:36:59]

Of course practice is key. And since this is our last week together, it’s really important that we focus on practice and inspiration. We’ve got 10,000 hours to accomplish, so why not 20,000 or 30,000 hours? I don’t want to spend too much time on theory, but since this is also a program on Madhyamaka, I would like to say a few words about the philosophy of Buddhist ethics. What does it mean to build an ethic, a theory of morals and ethics around non-self? There is a lot of material on Buddhist ethics in the pre-reading, and I really encourage you to read it.

The main point is that for most of us, our conventional Western ideas of morals and ethics are all based on free will and personal accountability. How can any of this work when there is no truly existing self? Jay Garfield makes a key point here, that action and ethics have to be based on dependent arising, the lack of a truly existing self, and not on the action of a free will bound by laws. Now, for those of us who have grown up in the West, this is very radical. We keep coming back to the notion of free will, we keep coming back to the idea of a self. We have seen it a lot in the Forum discussions, with the questions people ask about these things.

But as we saw in Week 5, we now know that the very idea of free will is already falling apart in the light of the findings of cognitive science. I think it’s quite intriguing that contemporary science might end up shifting Western thinking on morality and ethics – from a perspective that is based on self, to something that is much more aligned with the Buddhist perspective and not centred on a non-existing self. And yes, this applies very much to our politics, to our institutional structures, and to our organizations. For example, what does it mean to design a workplace around the idea of non-self? That’s a huge and fascinating topic, which we are not going to have enough time for this evening. We are going to focus much more on the personal implications, but I’d like to note that the broader social implications are all there as well.

Here’s a passage from the pre-reading that explores how we might begin to think about ethics in the light of non-self, from Garfield (2015) Engaging Buddhism (p.331):

Our identities are negotiated, fluid and complex in virtue of being marked by the three universal characteristics of impermanence, interdependence and the absence of any self. It is this frame of context-governed interpretive appropriation, instead of the frame of autonomous, substantial selfhood that sets metaphysical questions regarding agency, and moral questions regarding responsibility in a Buddhist framework. What is it to act, in a way relevant to moral assessment or reaction? It is for our behaviour to be determined by reasons, by motives we and/or others regard as our own. It is therefore for the causes of our behaviour to be part of the narrative that makes sense of our lives, as opposed to being simply part of the vast uninterpreted milieu in which our lives are led, or bits of the narratives that more properly constitute the lives of others. This distinction is not a metaphysical but a literary distinction, and since this kind of narrative construction is so hermeneutical, how we do so—individually and collectively—is a matter of choice, and sensitive to explanatory purposes. That sensitivity, on the other hand, means that the choice is not arbitrary. We can follow Nietzsche here. For what do we take responsibility and for what are we assigned responsibility? Those acts we interpret—or which others interpret for us—as our own, as constituting part of the basis of imputation of our own identities.

When I propose to jump from a window, for instance, in order avoid living through global warming and the decline of Australian cricket, the conditions that motivate my act are cognitive and emotional states I take to be my own, and which others who know me would regard as mine. The narrative that constructs the conventional self that is the basis of my individuation includes them, simply in virtue of our psychology and social practices. This, then, is, uncontroversially, although merely conventionally, an action, and is a matter of direct moral concern for me and for those around me.

If, on the other hand, you toss me from the window against my will, the causes of my trajectory lie in what we would instead, and uncontroversially, but again, on conventional, hermeneutical grounds, interpret as parts of your biography. This is no action of mine. The agency lies with you, not on metaphysical grounds, but on conventional grounds, not on the discovery of agent causation in your will, not in mine, but based upon the plausible narrative we tell of the event and of each other’s lives as interpretable characters.[45]

[Note 45]: It is important to remember that not all narratives are equally good. Some makes good sense of our lives, or those of others; some are incoherent; some are facile and self-serving; some are profound and revealing. It is possible for people to disagree about whether a particular event is an action or not, or about the attribution of responsibility. It is possible for us to wonder about whether we should feel remorse for a particular situation or not. These questions are in the end, on this account, questions about which narratives make the most sense. While these questions may not always be easy (or even possible to settle), the fact that they arise saves this view from the facile relativism that would issue from the observation that we can always tell some story on which this is an action of mine, and some story on which it is not, and so that there is simply no fact of the matter, and perhaps no importance to the question.

I’m not going to go into any more detail on the theory, but the takeaway for me here is the idea that accountability, agency, personhood, storytelling – all of these things are conventional narrative constructions. As we’ve been saying all of these weeks, the idea of the self is just a narrative we tell ourselves. In that sense you can talk about a selfless person and it can still make complete sense. We can have a conventional construct of personhood, which is completely empty of any truly existing self. I also very much recommend chapters 4 and 5 of Garfield’s book, on what is self and what is consciousness. And in particular he explores questions like what is the minimal conception of self that the Prasangika-Madhyamaka needs in order to actually engage in conventional truth. But enough theory. Let’s turn to practice.

Being honest with ourselves [t = 0:44:04]

Just as a reminder of what Rinpoche said, we should ensure that the core of our practice – and the foundation of our ethics – is being honest with ourselves. As Milarepa sang:

“My religion is not deceiving myself and not disturbing others.”

Here are a couple of quotes on this topic. First, from the character Irving Rosenfeld in the movie American Hustle:

As far as I could see, people were always conning each other to get what they want. We even con ourselves. We talk ourselves into things, you know, we sell ourselves things we maybe don’t even need or want. We’re dressing them up. We leave out the risk. We leave out the ugly truth. We don’t pay attention to that, because we’re all conning ourselves in one way or another, just to get through life.

It’s a lovely quote, and a wonderful basis for a meditation on where in your own life are you not confronting the truth. Is it in your relationships, your practice, your work, or some other aspect of your willingness to be honest about how your life is going?

Next, a quote from George Orwell’s “In Front of Your Nose,” which was published in the London Tribune on 22 March 1946:

The point is that we are all capable of believing things which we know to be untrue, and then, when we are finally proved wrong, impudently twisting the facts so as to show that we were right. Intellectually, it is possible to carry on this process for an indefinite time: the only check on it is that sooner or later a false belief bumps up against solid reality, usually on a battlefield.

I hope none of us gets into the situation where our views need to be refuted on the battlefield! But this goes back to what we talked about in previous weeks, where Rinpoche explained how the teachings are heard by three different kinds of student. Can we hear the truth? Or does it take some crisis in our lives before we are really willing to pay attention?

Work and relationships as a path [t = 0:46:07]

We can use life as a path, and as we’ve said this means using everything that we have in our life as an opportunity for practice. Using work as a path, using relationships as a path. And on that subject, I wanted to quote from Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet (#7) (Rome 1904):

It is also good to love: because love is difficult. For one human being to love another human being: that is perhaps the most difficult task that has been entrusted to us, the ultimate task, the final test and proof, the work for which all other work is merely preparation. That is why young people, who are beginners in everything, are not yet capable of love: it is something they must learn. With their whole being, with all their forces, gathered around their solitary, anxious, upward-beating heart, they must learn to love. But learning-time is always a long, secluded time, and therefore loving, for a long time ahead and far on into life, is: solitude, a heightened and deepened kind of aloneness for the person who loves. Loving does not at first mean merging, surrendering, and uniting with another person (for what would a union be of two people who are unclarified, unfinished, and still incoherent?), it is a high inducement for the individual to ripen, to become something in himself, to become world, to become world in himself for the sake of another person; it is a great, demanding claim on him, something that chooses him and calls him to vast distances. Only in this sense, as the task of working on themselves (“to hearken and to hammer day and night”), may young people use the love that is given to them. Merging and surrendering and every kind of communion is not for them (who must still, for a long, long time, save and gather themselves); it is the ultimate, is perhaps that for which human lives are as yet barely large enough.

Here’s another quote, from His Holiness the Dalai Lama, on how we might practice throughout our day, and use each day fully:

Every day, think as you wake up, today I am fortunate to be alive, I have a precious human life, I am not going to waste it. I am going to use all my energies to develop myself, to expand my heart out to others; to achieve enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. I am going to have kind thoughts towards others, I am not going to get angry or think badly about others. I am going to benefit others as much as I can.

This is a very practical aspiration, one we can all include in our day. And again, as we said in Week 1, if we are serious about engaging in post-meditation as deliberate practice – the 10,000 hours on the path to mastery – we can’t just be in cruise control. We have to test ourselves. It’s like a military commander would say: you only know your soldiers when they’re tested in the heat of battle. There’s a lovely quote from the martial artist Bruce Lee:

“Under duress, we do not rise to our expectations; we fall to the level of our training”

So how do we use our everyday life to always keep ourselves on the edge of our comfort zones, to always keep pushing into areas of challenge and discomfort? I really invite you to think about how much are you doing that right now in your everyday life – are you using your everyday life as a practice field for deliberate practice of the Middle Way?

And really, whatever your job is, that can be your practice field. The cultivation of worldly wisdom can also be part of our Dharma path – even making better decisions, making better choices, as we all have to make decisions all the time. And it’s not our goal to get things right in the world. We’re trying to renounce the world, to go beyond it – but we can still use the challenge of making decisions as a field of practice, like an artist might try and draw the perfect enso. We can use feedback from situations. We can use feedback from people around us to gauge our progress, to actually practice nonduality. So whatever you do, that is your practice field. As Rinpoche said, just as King Ashoka created probably one of the most conducive environments ever for the study and practice of Dharma, we’re going to need to think of how can we create something like that in the modern world. If we want an enlightened society, we will need Buddhist presidents, Buddhist CEOs, and Buddhist scientists. And if we would like to be a part of that, it’s not just a matter of learning to do our job well for the sake of benefitting others in a worldly way. We also need to learn to see our job as our practice field for cultivating the wisdom of the Middle Way. Even for Aristotle, the idea of practical wisdom or phronēsis (φρόνησις) was all about cultivating skill in worldly action, and this was an important part of the pursuit of the highest wisdom.

The management consulting firm McKinsey & Company, on its 80th anniversary, published a review of everything it had written about strategy, and it concluded that the difference between success and failure in strategy is not about trying to get the strategy right; it’s about not making stupid mistakes. And this is very similar to the way we approach our Dharma path, where progress is a result of elimination, and success is measured in terms of cleaning the dirt from our windows, and purifying our errors of judgment and understanding. Seeing the truth more clearly. And we can apply this same understanding when approaching emptiness in our work and our life – if we’re managers, if we’re strategists, if we’re artists, whatever our worldly profession might be – how can we use our profession as a way of practicing nonduality?

Self-transformation [t = 0:52:23]

In exploring how we might approach post-meditation, I’m going to go through both aspects of the path: self-transformation and then self-transcendence. So we’ll look at the Eightfold Noble Path and the Six Paramitas through both lenses. And we’ll also talk more about how when it comes to practice, Rinpoche made a very strong push that we should think of renunciation, lojong, and mind training. Dharma is not therapy. It’s not to make you happy, but to disrupt you. It is to go against your habits and your ego. It’s not to strengthen your daily life. So just always bear that in mind. When we think about worldly practice, we’re not doing it in order to find worldly happiness or to make our worldly life a success. Of course, Dharma is not against happiness or success either, but these are not our primary concern. Nevertheless, it’s quite possible that our Dharma practice may lead to greater happiness and success. We’re interested in our practice field, so we care that our actions are as fine as flour, just like Guru Rinpoche. So if we are managers, we want to manage well. If we’re artists, we want to paint well. But we’re not doing these things for the sake of worldly outcomes (such as happiness, productivity, stress relief or success), even if these might come. We are engaging in our post-meditation practice in the world for the sake of liberating ourselves and all sentient beings.

We talked in Week 1 about Aristotle’s question “What is the good for the city and the man?”, and there are so many answers throughout the history of philosophy. I came across a lovely example from Gandhi, where he was talking about what he called the seven social sins, which he lists as:

• Wealth without work

• Pleasure without conscience

• Knowledge without character

• Commerce without morality

• Science without humanity

• Worship without sacrifice

• Politics without principle

His commentary on the seven social sins is very succinct:

And naturally, our friend does not want to know these things merely through the intellect, but to know them through the heart, so as to avoid them.

So here he’s really talking about self-transformation. All of the items on his list are very worldly activities, the domain of post-meditation, and he’s asking how can we go about them in a way that will contribute to our spiritual progress? All of these trade-offs are trade-offs of judgment, they’re trade-offs of practical wisdom. So there are no straightforward answers about how to find the right balance or the middle way between extremes. This kind of good judgment comes from our practice.

For some, their practice leads to their view [t = 0:54:57]

I mentioned already this idea that Rinpoche said that for some their practice leads to their view, and for some their view leads to their practice. We’ll talk a little more about that. So first: practice leading to view.

We’ve talked about establishing the view, and then practicing it, but that’s difficult. The view is abstract; it’s inconceivable; we can’t understand it; and at the same time we have deep conventional habits of referring to our self, to objects, to the workings of cause and effect, to karma, rebirth, all kinds of things. All the phenomena of the everyday world. So for us, we need to start by loosening our grip on our samsaric habits and wrong views. And this is what is meant by merit. Changing the qualities of our subject, our perceiver. Cleaning the dirt off our window, so we can see more clearly. And we do that through practice.

So to take an example: generosity. Maybe when we start, we don’t feel it at all. It’s a pure chore. We do it because we’re told we have to. Maybe it becomes a habit over time. And then maybe after a while we actually start to feel it, when we give to somebody. And maybe even further down the line we might start to ask what is the idea of giving? Gift? Giver? Receiver? On what basis is wealth and fairness even part of society? What does it mean to give a gift?

If we really engage in generosity as a practice, we will find, over time, that it will start to undo some of our assumptions. We’ll start to question things. And by the way, if you’re giving to a charity, I would strongly suggest don’t make it a monthly direct debit, because you won’t be thinking about it. It’ll be out of your awareness. You won’t be meditating on it. We really want to practice the paramitas. We want to question our framing in terms of subject, object, and action, and go beyond that.

And so this is what is meant when Rinpoche says for some their practice leads to their view. But even though we may not have the view solidly in place yet, we’ve done enough, hopefully, in these eight weeks to understand the importance of not having an extreme view.

The story of Professor George Price [t = 0:57:16]

I’d like to tell the rather sad story of George Price, who was a professor in London. This is an example of what can go wrong when you have an extreme view of generosity, and don’t have the wisdom of nonduality to guide your action. The story may be found in ➜Wikipedia:

Professor George Price developed a new interpretation of Fisher’s fundamental theorem of natural selection, the Price equation, which […] still widely held to be the best mathematical, biological and evolutionary representation of altruism. […]

Price’s ‘mathematical’ theory of altruism reasons that organisms are more likely to show altruism toward each other as they become more genetically similar to each other. As such, in a species that requires two parents to reproduce, an organism is most likely to show altruistic behaviour to a biological parent, full sibling, or direct offspring. The reason for this is that each of these relatives’ genetic make up contains (on average in the case of siblings) 50% of the genes that are found in the original organism. So if the original organism dies as a result of an altruistic act it can still manage to propagate its full genetic heritage as long as two or more of these close relatives are saved. Consequently, an organism is less likely to show altruistic behaviour to a biological grandparent, grandchild, aunt/uncle, niece/nephew or half-sibling (each contain one-fourth of the genes found in the original organism); and even less likely to show altruism to a first cousin (contains one-eighth of the genes found in the original organism). The theory then holds that the further genetically removed two organisms are from each other the less likely they are to show altruism to each other.

If true, then altruistic (kind) behaviour is not truly selfless and is instead an adaptation that organisms have in order to promote their own genetic heritage. Price grew increasingly depressed by the implications of his equation. As part of an attempt to prove his theory right or wrong Price began showing an ever-increasing amount (in both quality and quantity) of random kindness to complete strangers. As such, Price dedicated the latter part of his life to helping the homeless, often inviting homeless people to live in his house. Sometimes, when the people in his house became a distraction, he slept in his office at the Galton Laboratory. He also gave up everything to help alcoholics, yet as he helped them steal his belongings, he increasingly fell into depression.

He was eventually thrown out of his rented house due to a construction project in the area, which made him unhappy because he could no longer provide housing for the homeless. He moved to various squats in the North London area, and became depressed over Christmas, 1974. Unable to prove his theory right or wrong, Price committed suicide on January 6, 1975.

It’s a really sad story, but it’s an example for all of us. If we try to apply generosity or any of the paramitas without an understanding of the view, it’s just going to become extreme.

Introduction to the eightfold path [t = 1:00:35]

Let’s start with the eightfold path. As you may know, this can be grouped into three aspects that comprise the trishiksha or the threefold training:

• Prajña (wisdom), which includes right view, and right intention or right thought.

• Shila (ethical conduct), which comprises right speech, right action, and right livelihood.

• Samadhi (mental discipline or meditation), which has three elements: right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

In practice terms, the usual order of practice or cultivation is to begin with shila or ethics, then to develop samadhi and mental discipline, and then finally prajña or wisdom. However, as we’ve spoken about previously, we can also think about the path in terms of view, meditation, and action. So you could also approach the three-fold training as prajña, samadhi, and shila. As Rinpoche says, for some people, practice leads to view; for some, view leads to practice. I want to emphasize that as we listen to the teachings of the eightfold path, even if we consider ourselves to be Mahayana or Vajrayana practitioners, we should never look down on the root yana, the Shravakayana. We can equally use all of these practices as nondual practices. This is our foundation.

The Shravakayana: The Noble Eightfold Path

1. Right view / right understanding (Samma ditthi) [t = 1:01:56]

We start with ‘right view’ or ‘right understanding’. And here I am taking the description of right view as set out in the book What the Buddha Taught (1974) by Walpola Rahula:

Right Understanding is the understanding of things as they are, and it is the Four Noble Truths that explain things as they really are. Right Understanding therefore is ultimately reduced to the understanding of the Four Noble Truths. This understanding is the highest wisdom which sees the Ultimate Reality.

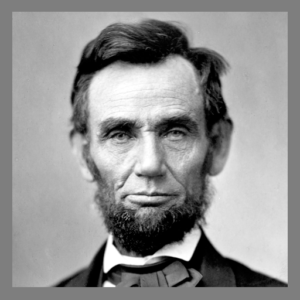

So that very much makes sense to us as students of the Middle Way. And in the Madhyamaka we would express the Four Noble Truths in terms of emptiness. And as we think about what this might mean in post-meditation, I’d like to offer a nice quote on view, on ultimate and relative, from Steven Spielberg’s movie Lincoln. This is the scene where Thaddeus Stevens, the passionate abolitionist who had no time for slave owning whites, scolds Abraham Lincoln for compromising with them. Lincoln’s goal was total abolition. And he believed passion matched with strategy would get us there. The scene in the movie goes like this:

[Thaddeus Stevens]: You claim you trust them—but you know what the people are. You know that the inner compass that should direct the soul toward justice has ossified in white men and women, North and South, unto utter uselessness through tolerating the evil of slavery. White people cannot bear the thought of sharing this country’s infinite abundance with Negroes.

[Abraham Lincoln]: A compass, I learnt when I was surveying, it’ll point you True North from where you are standing, but it’s got no advice about the swamps and deserts and chasms you’ll encounter along the way. If in pursuit of your destination you plunge ahead, heedless of obstacles, and achieve nothing more than to sink in a swamp, what’s the use of knowing True North? Our virtues become vices when they blind us to the complexity of living. If you are a compass, keep pointing. If you are a map maker, we have work to do. Real progress depends on it. And first, we must understand the landscape. Sometimes, to cross the river, you have to backtrack. But by God we’ll cross it.

This is a lovely expression of the Two Truths. Yes, we know that right view is emptiness in the ultimate truth (the compass pointing to True North), but we also know that this does not in any sense mean we should despise the complexity of the conventional truth (and the need for a map to help us navigate the swamps and deserts and chasms). We need both compass and map.

2. Right intention / right thought (Samma sankappa) [t = 1:04:14]

Next, Walpola Rahula on right intention, once again from What the Buddha Taught (1974):

Right Thought / Right Intention denotes the thoughts of selfless renunciation or detachment, thoughts of love and thoughts of non-violence, which are extended to all beings. It is very interesting and important to note here that thoughts of selfless detachment, love and non-violence are grouped on the side of wisdom. This clearly shows that true wisdom is endowed with these noble qualities, and that all thoughts of selfish desire, ill-will, hatred and violence are the result of a lack of wisdom — in all spheres of life whether individual, social, or political.

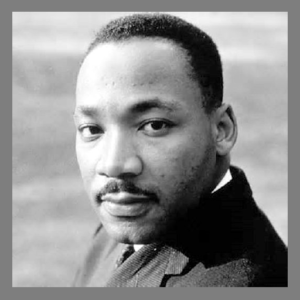

This is a profoundly important question: how do we cultivate the right intention? We have already encountered the aspiration practices of the Four Immeasurables (love, compassion, joy and equanimity) that are part of the training in relative bodhicitta. However, the idea that love is on the side of wisdom is found in almost all spiritual traditions. There’s a lovely quote from Martin Luther King Jr. on “Loving Your Enemies”, which is obviously in a Christian context, though I would encourage you to focus on the nondual meaning. He says,

The meaning of love is not to be confused with some sentimental outpouring. Love is something much deeper than emotional bosh. Perhaps the Greek language can clear our confusion at this point. In the Greek New Testament are three words for love. The word eros is sort of aesthetic or romantic love. In the Platonic dialogues eros is the yearning of the soul for the realm of the divine. The second word is philia, a reciprocal of love and the intimate affection and friendship between friends. We love those whom we like, and we love because we are loved. The third word is agape, understanding and creative, redemptive goodwill for all men. An overflowing love which seeks nothing in return, agape is the love of God operating in the human heart. At this level, we love men not because we like them, nor because they possess some type of divine spark; we love every man because God loves him. At this level, we love the person who does an evil deed, although we hate the deed that he does.

Now we can see what Jesus meant when he said, ‘Love your enemies.’ We should be happy that he did not say, ‘Like your enemies.’ It is almost impossible to like some people. ‘Like’ is a sentimental and affectionate word. How can we be affectionate toward a person whose avowed aim is to crush our very being and place innumerable stumbling blocks in our path? How can we like a person who is threatening our children and bombing our homes? This is impossible. But Jesus recognized that love is greater than like.

We might not use that language exactly, but I think this is a wonderful example of the idea of common humanity that we’re cultivating as we practice bodhicitta. This is the equanimity of wanting to see – and to treat – all sentient beings the same way as we extend our love, our compassion, our joy, and our equanimity. And as we saw in previous weeks, this is also an emptiness practice. So notice for yourself – can you love all people equally, as Martin Luther King sets out, or not? And if you cannot, then you can invest in the path of self-transformation to transform whatever defilements are stopping you from seeing them in that way. And as with all elements of the eightfold path, this is a meditation practice – but it is also a post-meditation practice, as our daily lives give us countless opportunities to practice right intention.

3. Right speech (Samma vaca) [t = 1:07:21]

Here is Walpola Rahula on right speech:

Right Speech means abstention (1) from telling lies, (2) from backbiting and slander and talk that may bring about hatred, enmity, disunity and disharmony among individuals or groups of people, (3) from harsh, rude, impolite, malicious and abusive language, and (4) from idle, useless and foolish babble and gossip. When one abstains from these forms of wrong and harmful speech one naturally has to speak the truth, has to use words that are friendly and benevolent, pleasant and gentle, meaningful and useful. One should not speak carelessly: speech should be at the right time and place. If one cannot say something useful, one should keep ‘noble silence’.

For most of us, our worldly lives are lived in the realm of communication, whether written or verbal, so once again we have many opportunities each day to cultivate awareness and practice right speech. For example, we might choose to notice how are we reactive? In what ways does our communicate arise from a desire to manipulate others? To be liked? To be popular? To get ahead? How are we manifesting the eight worldly dharmas in our communication? Once again, this offers another perfect opportunity for emptiness practice in post-meditation, just to really hold ourselves to account.

Conflict and nonduality [t = 1:08:36]

Working with conflict is not explicitly part of the eightfold noble path, but here we could also, in parentheses, talk a little bit about conflict, because conflict is endemic in samsara – in relationships, in work, in politics. And if you think about it, conflict is the ultimate expression of duality, and working with the conflict in our lives is an excellent practice of nonduality. Conflict arises when we reify the world into self and other, when we create solid boundaries with different interests, even when it’s a boundary between two parts of ourselves. As we saw in Week 7, we are prone to hesitation and doubt, and that is typically due to inner conflict – for example, between our habitual instincts and our desire to practice the Dharma. And in the end, all conflict comes down to incorrect or incomplete dualistic maps of the world.

We have also talked about how do we bring the Dharma to the West. How might we understand the relationship between Dharma and science, or Dharma and western philosophy, or Dharma and the understanding of mind and consciousness? Many of us may see conflicts there. Again, we are imposing our dualistic frames onto the world. How can we work with that? Another ubiquitous manifestation of conflict is change. For example, as practitioners we seek to change from the current version of ourselves to the desired future version of ourselves. Even as bodhisattvas on the path, any change involves conflict.

Working with conflict, then, is a practice of nonduality. And there’s a lot more we could say that goes beyond the scope of what we’re going to cover tonight, but let’s briefly go back to what Rinpoche said about elegance and outrageousness. As we saw, outrageousness means going beyond our habitual, socialized, tribal self:

[win/lose]: As we learned from Bob Kegan at Harvard, when we’re operating from the socialized self, we’re fixed to the views of our tribe or our family or our society or whatever, and so conflict becomes hardened. It becomes win/lose. We can’t go against our loyalty to our tribe, or loyalty to our ideas and our positions.

[win/win]: But once we go to a self-authoring self, which corresponds to what Rinpoche calls “outrageous”, we can then have find win-win outcomes, because now we are flexible. We can self-author, so we can change our views. Our views are not determined in terms of loyalty to our tribe.

[letting the conflict transform us]: And then of course, finally, we transcend all views – the self-transcendence that we’ve already talked of. We go beyond even self-authorship to self-transcendence; and now, it is nondual. It’s not about a win-win anymore; it’s not about resolving a conflict. It’s about letting the conflict transform us, using it as a resource to become aware of our own defilements. So that is conflict as nondual practice.

Mastering conflict is just as in the rest of our emptiness practice. We learn to understand our wrong views, our incomplete maps, our bad assumptions, and our internal conflicts. We become aware when we are in over our heads, when we have opposing or conflicting rules that we cannot make sense of, an incomplete map internally. And so we ask ourselves: can we learn to listen, rather than react? Can we learn to find wisdom in our opponent’s position? Rather than assume that we know what’s right, how can we learn to look for the truth? To deliberately question? To approach a conflict with beginner’s mind? And of course it’s hard, because usually in a conflict, we’re emotionally triggered. We become defensive. We withdraw into ourselves. We’re less likely to extend ourselves to our opponent. So how can we regain our centre and reconnect with our bodhisattva aspiration? It’s such an important practice.

4. Right morality / right discipline / right action (Samma kammanta) [t = 1:12:21]

Here is Walpola Rahula on right discipline or right action:

Right Action aims at promoting moral, honourable and peaceful conduct. It admonishes us that we should abstain from (1) destroying life, (2) from stealing, from (3) dishonest dealings (lying), from (4) illegitimate sexual intercourse, and that (5) we should also help others to lead a peaceful and honourable life in the right way.

Traditionally, we think of discipline and morality in terms of the five vows of abstaining from harming living beings, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, and intoxication. One important way we can bring our view of emptiness to our practice of discipline is, as we saw in Chapter 2 of Madhyamakavatara, by not becoming puritanical. Not thinking we are superior in terms of our morality, our ethics, or our Dharma. Not thinking that our understanding is better or that our practice is better. And as we mentioned earlier, Rinpoche is talking a lot nowadays about “bad Buddhists” – people who don’t necessarily hold to all of the five vows – just ordinary householders. Instead of judging them for their supposedly inferior discipline, how might we ensure that we do not exclude them from the Buddha’s wisdom and compassion? Once again, this is an opportunity to watch ourselves. When we think about our discipline, is it becoming something tribal, something self-referential, something exclusionary? Or is it a genuine practice by which we aspire to benefit others?

5. Right livelihood (Samma ajiva) [t = 1:13:44]

Here is Walpola Rahula on right livelihood:

Right Livelihood means that one should abstain from making one’s living through a profession that brings harm to others, such as trading in arms and lethal weapons, intoxicating drinks, poisons, killing animals, cheating, etc., and should live by a profession which is honourable, blameless and innocent of harm to others. One can clearly see here that Buddhism is strongly opposed to any kind of war, when it lays down that trade in arms and lethal weapons is an evil and unjust means of livelihood.

So how might that relate to emptiness? Well, Rinpoche talks a lot about not getting caught up in the rat race, in fame and fortune, in worldly success. He has talked about one of the best jobs as being a plumber. How many of us would really embrace that? I’m pretty sure that’s why he chose that example. We have all these glorious ideas of success or inspiration or passion or fulfilment – all these samsaric delusions. I think the other way we can think about it is in terms of interdependence, looking at our roles as producers and consumers, looking at the products we buy, looking at the impacts of our actions, their upstream and downstream consequences. What are the social impacts? What are the environmental impacts of how we live? Of what we buy? We can choose to take this very seriously, as part of a practice of emptiness. Why not?

6. Right effort (Samma vayama) [t = 1:15:05]

Here is Walpola Rahula on right effort:

Right Effort is the energetic will (1) to prevent evil and unwholesome states of mind from arising, and (2) to get rid of such evil and unwholesome states that have already arisen within a man, and also (3) to produce, to cause to arise, good and wholesome states of mind not yet arisen, and (4) to develop and bring to perfection the good and wholesome states of mind already present in a man.

This is self-explanatory. Perhaps it may serve as a reminder if we start to think of our practice of emptiness in passive, disengaged or nihilistic terms. Far from it: it is active and energetic.

7. Right mindfulness / right attentiveness (Samma sati) [t = 1:15:31]

Here is Walpola Rahula on right mindfulness:

Right Mindfulness (or Attentiveness) is to be diligently aware, mindful and attentive with regard to (1) the activities of the body (kaya), (2) sensations or feelings (vedana), (3) the activities of the mind (citta) and (4) ideas, thoughts, conceptions and things (dhamma).

These are the four foundations of mindfulness, which we have also talked about in previous weeks. And this is very much a core emptiness practice. First, learning to see all phenomena as impermanent, and eventually seeing them all as empty and without inherent existence. Seeing all our narratives and views as empty, including the view of emptiness itself – we already talked about the emptiness of emptiness in Week 6. As we cultivate right mindfulness, we realize that none of these four kinds of objects of mindfulness, none of the skandhas, are “me” or “self”. And so if we do this properly, mindfulness becomes an experiential way to establish the lack of true existence of the person. Just as we can establish the view intellectually through the study of the Madhyamaka, we can establish the view experientially through the practice of right mindfulness.

And as we’ve said in previous weeks, this approach to the practice of mindfulness as an experiential introduction to the view of emptiness is very different from how mindfulness is currently taught in the West, where it’s all about solidifying the self and worldly ambition. Most contemporary mindfulness teachings are marketed with the claim that this practice will make us more successful, more productive, less stressed, more happy and so on. If we practice mindfulness in this way, it will merely entangle us more deeply in samsara and the eight worldly dharmas. As with the other elements of the path, our intention determines everything.

8. Right samadhi / right concentration (Samma samadhi) [t = 1:16:50]

Here is Walpola Rahula on right samadhi or right concentration:

The third and last factor of Mental Discipline is Right Concentration leading to the four stages of Dhyana, generally called trance or recueillement.

(1) In the first stage of Dhyana, passionate desires and certain unwholesome thoughts like sensuous lust, ill-will, languor, worry, restlessness, and sceptical doubt are discarded, and feelings of joy and happiness are maintained, along with certain mental activities.

It’s just worth pointing out that mental discipline leads directly to the removal of unwholesome mental states and defilements. I know some of us in recent weeks have talked about skepticism as being a positive quality that we westerners like to believe we possess. But we now know that according to the teachings, if we’re actually practicing correctly, then even when we reach the first of the four stages of dhyanas, our skepticism and negativity will go. This is another helpful indicator of our progress on the path of practice. Rahula continues:

(2) In the second stage, all intellectual activities are suppressed; tranquillity and ‘one-pointedness’ of mind developed, and the feelings of joy and happiness are still retained.

(3) In the third stage, the feeling of joy, which is an active sensation, also disappears, while the disposition of happiness still remains in addition to mindful equanimity.

(4) In the fourth stage of Dhyana, all sensations, even of happiness and unhappiness, of joy and sorrow, disappear, only pure equanimity and awareness remaining.

So here we can see that even in the Shravakayana, our practice is very much oriented towards the idea of equanimity and awareness, which is also central to the Heart Sutra. As we know from our discussion of the Heart Sutra in Week 6, form is emptiness and emptiness is form. And likewise, awareness is emptiness and emptiness is awareness. This is the truth, the nature of phenomena, the nature of mind. And since the aim of our practice is to realize the truth, to familiarize ourselves with the truth, we understand that our practice is about the cultivation – or perhaps it would be better to say realization – of the qualities of emptiness and awareness. Or using the Shravakayana language, we can say equanimity and awareness. And so it goes without saying that right concentration is also very much an emptiness practice. I think for many of us we’re very attached to our emotions and our practice experiences, especially so-called positive experiences like joy or happiness, or insight, or visions of the Buddha and so on. But all this has to go. And to the extent that we are either attached to these positive emotions and meditation experiences, or even actively seeking to reproduce or strengthen them, this is an obstacle for our practice. As Rinpoche said, our practice is not for happiness.

Advice on post-meditation practice [t = 1:19:02]

Many of you wrote to me and asked, is there some practice advice for how we can approach post-meditation and specific worldly activities? There’s a short teaching from Rinpoche which might help here, called “Applying the Three Supreme Methods“, which are sometimes called “good in the beginning, good in the middle, and good in the end”:

Applying the Three Supreme Methods

Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche

If one approaches an offering of service with basic good intention, then one accumulates merit, but when three wholesome attitudes known as the Three Supreme Methods are genuinely applied, an outwardly mundane task can even become a paramita.

(1) Intention

To apply the Supreme Methods, begin by refining your intention, thinking you will perform the work for the sake of all sentient beings. Remember you are not making an offering of service to boost your self-gratification, recognition, or mileage points. As Shantideva said, look upon yourself as a utensil and think: I have offered my body to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

May I be a guard for those who are protectorless,

A guide for those who journey on the road.

For those who wish to go across the water

May I be a boat, a raft, a bridge.

Since it is going to be very difficult to remember to apply the three wholesome attitudes with every page you photocopy or every stroke of the scrub brush, before beginning a day of volunteer work, students should recite the following prayer:Even the remembrance of your name dispels the hope and fear of nirvana and samsara.

From now until attaining enlightenment, I take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

Following all the bodhisattvas of past, present, and future, may I emulate their infinite activity to free beings from suffering.

Eventually may I manage to surrender everything I have – my time, my space, my belongings, and even my very limbs – for the sake of all beings.

In that aim, I shall begin by sacrificing my energy and time today to . . . (insert whatever the task is – copying, cleaning the teaching hall, shovelling snow).

(2) Emptiness