Alex Li Trisoglio

Aspiration: Week 3 – Foundation

March 30, 2024

75 minutes

Reference: Samantabhadra’s King of Aspiration Prayers, verses 1 – 12

Introduction to Week 3

Engaging in preliminaries in order to accumulate merit

Welcome to week three of our journey exploring the Pranidhana-Raja and how it serves as a profound expression of the Bodhisattva’s path toward enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. Week 1 was the program introduction, and last week in Week 2 we went through the verses on the benefits of reciting and practicing this King of Aspiration Prayers. We have already touched on the text’s focus on infinite aspiration, and this week we will dive into the importance of preparatory practices in cultivating the conditions necessary for spiritual growth and the actualisation of this infinite or inconceivable aspiration.

This week we’ll be covering the first twelve verses of the prayer which comprise the Seven Branch Offering. This is a comprehensive set of practices meant to purify the mind and the heart — to cultivate merit, to purify negativities, and foster the development of bodhichitta — which is the mind aspiring towards enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. As we’ve seen in previous weeks, the Pranidhana-Raja is deeply revered in Mahayana Buddhism for its profound expression of the aspiration of bodhichitta and also how it lays the groundwork for the bodhisattva’s infinite journey. And in Tibetan Buddhism, these twelve verses are often recited as a standalone prayer.

The Seven Branch Offering has seven preliminaries: prostration, offering, confession, rejoicing, requesting the Buddhas to turn the wheel of dharma, requesting them not to enter nirvana, and dedication. Each practice addresses specific afflictions and karmic obstacles, functioning as antidotes that prepare the practitioner for the profound aspiration toward enlightenment. For those of you who are ngöndro practitioners, you’ll also recognise these practices as the foundations of the ngöndro or the preliminary practices. And in the same way that the practice of ngöndro in the Vajrayana allows us to accumulate the merit to successfully practice sadhana, these twelve verses could be considered as a ngöndro for the Pranidhana-Raja itself — enabling us to engage more fully in the inconceivable verses that lie ahead of us.

Approaching the verses on both a relative and more ultimate level

This week we’ll go through these seven preliminaries both on the more relative and material level and also on the level of emptiness and non-duality — seeing them both as a preparation for the later verses that focus more on emptiness and inconceivability and also as an expression of this vast Mahayana view and an opportunity to integrate this non-dual view into practice, even in these so-called preliminaries. Hence the image for this week is of inconceivable offerings.

This is also an opportunity to acknowledge the natural presence of doubts and hesitations on the spiritual path. These initial verses, while serving as preparatory practices, are also an opportunity for us to reflect on our own aspirations and doubts that may arise as we consider how we might commit to a practice. This kind of reflection is not a hurdle but could be seen as an integral part of the journey deepening the practitioner’s commitment and understanding. This session is also an invitation to embark on an inner journey that mirrors the infinite aspiration of the Bodhisattva. So I encourage you to see these verses not merely as an object for academic study, but an opportunity for deeply personal engagement with the practices to cultivate the ground for spiritual awakening. And I’d like to encourage you to approach the session with openness to experiencing both the aspirations and the doubts as vital aspects of your path.

So let us journey through the verses with the heart of a Bodhisattva aspiring to benefit all sentient beings, and as we did last week, let’s take a moment to tune our motivation and set our intention.

[Pause]

Prologue

So let’s turn to the verses. In introducing them, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche said “In order to make your aspiration powerful or even to actually have the ability to aspire, we need a few preparations”. He said “These are sort of easier parts, so I’m going to go through them very quickly”, which he did in general. But I will say that because these verses are also covering material that was in the Bodhisattva teachings — his teachings on Shantideva’s Bodhicharyavatara (The Way of the Bodhisattva) — and also in the Longchen Nyingtik Ngöndro teachings, he has actually taught these topics in very great depth some 20 years ago. So I wouldn’t take his words to imply that these verses are simplistic, but rather that we have a lot of material at our disposal already to study and practice them.

He said that in order to create this ability to aspire we try to accumulate merit by doing these seven limb practices. And as Buddhists we are followers of cause and effect, so first we need to persevere in gathering the necessary positive causes and conditions to fulfil this prayer. And we’re all doing our best to cultivate aspiration and to put our aspiration into practice, but of course it doesn’t always work out the way we intend. And this gap between our aspiration and our action is considered a lack of merit or the lack of causes for fulfilling the aspiration, which brings us back to habits and training. To use the mountain climbing analogy we used last week, if we don’t have the right equipment or if we haven’t adequately invested in our physical fitness we may not be able to complete the climb. However Bodhisattvas don’t give up in the face of challenges, they redouble their aspiration and their practice so that things will be different going forwards.

Rinpoche also said one may wonder, “For how long should we aspire?” And he said there are innumerable or infinite sentient beings as infinite as the sky, and as infinite as these sentient beings there are also infinite numbers of defilements and emotions, and so the Bodhisattva’s aspiration will also be infinite. So as he said, “This is a long term project”, he said “Actually, long is not the right word, this is a forever project. We should kind of really give up on the idea of getting enlightenment, we should instead pray that forever and ever we will be practitioners of this Pranidhana-Raja and that this is the only thing we will do, that should be our aspiration”.

1. Prostration (verses 1 – 2)

So with that context, the first of the seven branches is prostration, which is verses 1 and 2 of the prayer. Prostration which is also about reverence, involves showing respect and veneration towards the Three Jewels: the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. Prostrations are both physical and mental acts of humility and devotion, acknowledging the qualities of the enlightened ones.

1.1. Prostration

[1] To all the buddhas, the lions of the human race,

In all directions of the universe, through past and present and future:

To every single one of you, I bow in homage;

Devotion fills my body, speech and mind.

[2] Through the power of this prayer, aspiring to Good Action,

All the victorious ones appear, vivid here before my mind

And I multiply my body as many times as atoms in the universe,

Each one bowing in prostration to all the buddhas.

Visualisation and approach

In commenting on these verses, Rinpoche talked a little bit about the visualisation. He said that because of the power of the aspiration, “It doesn’t take any time to gather all these Tathagatas of the ten directions and three times. The moment you want to aspire, they’re all there, ready to be your witness, ready to be your support”. And he said, “I guess amongst all these hundreds and thousands of Buddhas, you should not forget the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra, silently riding this giant beast, his elephant”. He said he always likes to visualise hundreds of other elephants, sort of slowly moving. He said, “I don’t know if you’ve ever seen elephants. They’re very silent. They’re the biggest animals. But when they walk, you don’t know. And also they have the most beautiful eyes. They have the most beautiful way of looking at you. They see you, but they always make you feel like they’re not looking at you”. Yes, so visualising thousands of elephants would be good. In Tibetan this is considered a “tendrel”, an auspicious coming together of causes and conditions that creates a good outcome.

And the person — ourself — offering prostration is not just a single human making a single prostration, but one can imagine oneself manifesting in infinite numbers, as many as the atoms that could possibly exist in the whole universe. We might think of this perhaps as a Vajrayana method, but this is also a Mahayana way of thinking, a Mahayana attitude. So first with the body, we offer prostration thinking that there are as many bodies as there are atoms in the universe prostrating along with us. And to whom do we prostrate? The Buddhas of the past, the present, and even those Buddhas who have not yet become Buddha — the future Buddhas. So as Rinpoche said, even here, right at the beginning, the ordinary concept of time is already broken. Even in these very first verses, we’re already embracing the vast and inconceivable view of non-duality.

The essence of prostration is to surrender. So when we are prostrating, we are mentally surrendering to a person that we consider valid, the enlightened person who is non-deceiving. I think it’s worth considering — who in our ordinary lives are we are willing to bow down to, so to speak? Who do we wish to emulate? Who do we respect? Who do we surrender to? Who are we willing to follow? Who are our role models? I dare say, who are the influencers in the online world that we follow? Perhaps we can ask ourselves, who are we effectively prostrating to, without necessarily thinking of it in those terms?

The Seven-Branch Offering for ngöndro practitioners

Going back to the visualisation, in some of the other commentaries, it says that those with sharp mental faculties can think of the array of pure fields of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in the multitude of the ten directions as being present right here with us in this room. However the commentaries also say that for beginners, it’s advised to visualise the field of accumulation or the field of merit — which those of you who are practicing ngöndro are familiar with — so the focal object can appear more easily. Of course, ultimately we would love to be able to practice this with infinite copies of ourselves prostrating to infinite Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in all the times and directions. But as beginners, it may be more straightforward for us just to imagine a single field of merit, a single Buddha surrounded by Bodhisattvas and sentient beings, rather than to get lost in an overcomplicated visualisation. And we can aspire that as our practice becomes more stable, more solid, that we can increasingly add this added dimension of inconceivability to our visualisation.

So as I’ve already mentioned, this is a Mahayana text, but I know many of you listening to this are Vajrayana practitioners who are practicing ngöndro or Guru Yoga or sadhana practice. And there are others who are interested in the Vajrayana path and not yet practitioners. So although the Vajrayana is beyond our scope today, I would like to say that in my view it’s the most profound technique or technology that I know of for actualising the core Mahayana view of “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form”. In other words, it is the most profound and powerful technique to allow us to go beyond mere intellectual understanding of these words — though that is already difficult — and turn them into lived experience. And perhaps even more important, it can help cultivate a lived experience of emptiness and non-duality, even in those among us who struggle with the intellectual understanding of this profound view.

Longchen Nyingtik Ngöndro and Chetsün Nyingtik Ngöndro

So in the spirit of ngöndro, I want to turn briefly to the Longchen Nyingtik Ngöndro and the words in the commentary, Patrul Rinpoche’s “Words of My Perfect Teacher”, the Kunzang Lamé Shyalung. You’ll find the commentary on the Seven-Branch Offering appears in the section on Guru Yoga. And here Patrul Rinpoche says:

For this practice, visualise that you are emanating a hundred, then a thousand, then innumerable bodies like your own, as numerous as the particles of dust in the universe. And at the same time, visualise that all beings, as infinite as space itself, are prostrating with you.

Among Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s students, some are doing Longchen Nyingtik Ngöndro, some are doing Chetsün Nyingtik Ngöndro, and some are doing other ngöndros. And in both the Longchen Nyingtik Ngöndro and Chetsün Nyingtik Ngöndro, this Seven Branch Offering appears in the Guru Yoga after the initial visualisation and invocation, and before the supplication or maturing the siddhi, which in turn comes before invoking the blessing. So the location of the prayer in these guru yogas is the same, but the language of course is quite different between different practices. And for the Seven Branch Offering, the Chetsün Nyingtik Ngöndro has language that is more non-dual, I suppose one could say. So in Longchen Nyingtik, the line is:

I prostrate, emanating as many bodies

As there are particles of dust in the whole universe.

And in the Chetsün Nyingtik, it says:

I prostrate beyond meeting and separation.

These ideas like “beyond meeting and separation” can be challenging to understand and put into practice, especially for beginners like us. We will come back to emptiness again and again over the coming weeks, and we shall hope to deepen our appreciation of words such as these. But the key point in both practices is that the Seven Branch Offering is there to accumulate merit before the supplication and invoking the blessing in the Guru Yoga. And invoking the blessing is none other than realising the nature of mind, which is none other than realising emptiness and non-duality. And so in that way, the Vajrayana form of practice is doing something very similar to what we’re doing in the Pranidhana-Raja. In both cases, we begin with preliminary practices to accumulate merit, so that when it comes to realising the nature of emptiness — which is realising the nature of mind, which is receiving the blessings of the guru — we have accumulated enough merit so that stage of our practice (i.e. engaging in the more emptiness-oriented verses of the Pranidhana-Raja, or receiving the blessings in the Guru Yoga) has a more profound effect.

An everyday application: practicing in the grocery store

I would also like to give an everyday example for each of these seven branches. And I encourage you to think about how you might find ways in your own daily life to bring this to life in your moment-to-moment activities. Let’s consider the example of going to a grocery store. How might you apply this first branch of prostration or reverence in that example? Well, while you might not physically prostrate in a grocery store, you can practice this principle by cultivating a mindset of gratitude and respect. You can acknowledge the effort of countless individuals involved in producing and delivering the food to the shelves, from farmers to truck drivers to store employees. And this acknowledgement can help cultivate humility and a sense of interconnectedness. So I really invite you to be very creative with this kind of contemplation and visualisation and practice. Find a way of making it come alive in your own life, whether it’s when you’re out in the world or at work, whether you are with your family, with your children, or with your friends. Find ways of asking yourself, “What would it mean to practice the Seven Branch Offering in this context, here and now?

2. Offering (verses 3 – 7)

The second branch is offering, verses three to seven. And here we make offerings, both material offerings — like flowers, incense, light, and so forth — and immaterial offerings, such as the offering of our practice or our merit or our virtues. These offerings are made without any attachment or expectation of reward, aiming to cultivate generosity and reduce greed.

1.2. Offering

[3] In every atom preside as many buddhas as there are atoms,

And around them, all their bodhisattva heirs:

And so I imagine them filling

Completely the entire space of reality.

[4] Saluting them with an endless ocean of praise,

With the sounds of an ocean of different melodies

I sing of the buddhas’ noble qualities,

And praise all those who have gone to perfect bliss.

[5] To every buddha, I make offerings:

Of the loveliest flowers, of beautiful garlands,

Of music and perfumed ointments, the best of parasols,

The brightest lamps and finest incense.

[6] To every buddha, I make offerings:

Exquisite garments and the most fragrant scents,

Powdered incense, heaped as high as Mount Meru,

Arranged in perfect symmetry.

[7] Then the vast and unsurpassable offerings—

Inspired by my devotion to all the buddhas, and

Moved by the power of my faith in Good Actions—

I prostrate and offer to all you victorious ones.

So with these verses, we declare the glory and the greatness of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to the three worlds, and then we offer whatever we human beings can think of as good and worthy of offering. For instance, flowers, garlands, music, perfume, parasols, lamps. Here Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche said, “Each of these is very romantic. You have to think about being in India 2,500 years ago. Maybe nowadays you might give someone an iPhone charger, but 2,500 years ago there was no electricity. So it’s such a beautiful gift to give someone a lamp, ready-made with oil and wick, especially to the sublime beings, incense, robes, all kinds of food, soap, bathrobes, toothpaste, basically whatever comes into your mind”. In other teachings he has encouraged us to offer anything from this relative world that we consider valuable or desirable — things like swimming pools, beaches, even the lifestyles of influencers on social media. Whatever it is that we value, we offer to all of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

The unsurpassable or inconceivable offering

The last of these verses, the seventh verse, is the unsurpassable or inconceivable offering, which cannot be conceived of by this limited human mind. So how are we supposed to make an inconceivable offering? For beginners, when we offer something like a flower, we typically think this is a flower, nothing more, nothing less. So Rinpoche says that “To make it into an inconceivable offering, when you offer a flower, you can think that it is not just a flower, but that it is infinite foods, drinks, basically all the phenomena that can be included in samsara and nirvana”. And at a glance, when we think that way, it would seem that it’s just a mental fabrication. But Rinpoche insisted it’s not just a mental fabrication, because if we think deeply, we realise even in the case of just one flower, because of different perceptions of different sentient beings, they all perceive it in very different ways. For example, if a goat were to wander in right now, probably the goat would relate to that flower as food, rather than we might relate to it, and so on.

So for the time being, for beginners like us, those of us who are on what’s called “the stage of aspiring conduct”, in other words, the first two of the five paths — which are the Path of Accumulation and the Path of Joining — the way to make an inconceivable offering is to approach it in this way, and to think that one flower is not just one flower, but everything that could exist. However, when teaching the King of Aspiration Prayers in Bodh Gaya in 2023, Rinpoche said, “For those of you who are meditators, in other words for those who are able to not follow the past thought or anticipate the future thought, but who can remain in the present moment without fabricating or constructing anything — that is the actual inconceivable offering.” And he has also said that if you can practice in that way, then it is not just the inconceivable offering, but it is also the prostration, confession, rejoicing — in fact, it’s all of the seven branches. If you are able to do that, that is the highest and best way of practicing each and every one of these seven branches.

So returning to the Words of My Perfect Teacher, for this second branch Patrul Rinpoche said:

Set out as many offerings as your resources permit, as was explained in the chapter on the mandala offering – that is to say, using clean and perfectly pure offerings, and without being ensnared by miserliness, hypocrisy or ostentation. These offerings are just the support for your concentration. Then make a mental offering in the manner of the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra.

So even there, you can see that the ngöndro commentary is referring to this prayer. Also, it’s suggesting that for those of us who want to make this Pranidhana-Raja into more of a formal practice, we can also set up our shrine with offerings as we would if we were practicing the mandala offering. So I think you can think of it in both ways. You can practice the ngöndro by making offerings with the vast and inconceivable aspiration of the Pranidhana-Raja, and you can practice the Pranidhana-Raja more formally by setting out offerings as you would when practicing the ngöndro.

Returning to the example of the grocery store, you might wish to make your shopping trip an act of generosity. Perhaps you might buy something with the intention of giving it to someone else, perhaps a friend, a family member or a neighbour. This could also extend to donating to food banks or participating in store initiatives that support those in need. The key is to give without seeking anything in return, and thereby cultivating a generous spirit.

3. Confession (verse 8)

The third branch is confession or purification. In this branch, we reflect on our past negative actions and thoughts, openly confessing them with a sincere heart of repentance. This practice is crucial for purifying negative karma and fostering a clear conscience and moral integrity. There is just one verse here:

1.3. Confession

[8] Whatever negative acts I have committed,

While driven by desire, hatred and ignorance,

With my body, my speech and also with my mind,

Before you, I confess and purify each and every one.

We understand virtue in terms of what takes us closer to the truth

Here Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche explained that this third cause for accomplishing aspiration is to confess all our negative actions of body, speech and mind that we have committed from beginningless time until now, in their entirety. And here the Bodhisattva path has a somewhat unique attitude, in that we can confess negative actions even if we may not remember or realise that we have committed them. This attitude of confessing something we cannot recall having done is a much grander way of thinking about accountability. And in Buddhism, the concept of negative actions is quite vast. Fundamentally, it’s about what takes you away from reality or what takes you away from the truth. Last week, we talked about not having non-virtuous or evil companions, and that was based on the same idea. As Rinpoche said, when we talk about non-virtuous companions, it isn’t so much about friends who might distract you by inviting you to the movies, but rather people who turn you away from the Dharma in some way. As Dharma practitioners, what we want always comes back to reality and truth.

Rinpoche has often explained that in Buddhism, the way we think about ethical or moral behaviour — the way we think about good and bad — is quite different from the Western Abrahamic or Judaeo-Christian way of thinking about good and evil. There have been lots of questions during the various teachings when Rinpoche has taught this Pranidhana-Raja, asking about how we can behave ethically or do good with our lives. And I think for those of us who have grown up with more of a Judaeo-Christian cultural background, we can sometimes confuse that way of thinking about good and bad with the Buddhist approach, which is much more about approaching virtue in terms of understanding truth and understanding reality — and therefore approaching non-virtue in terms of ignorance and not understanding the truth.

Patrul Rinpoche’s commentary in the Words of My Perfect Teacher is relatively brief. He says:

With this thought, we confess as explained in the chapter on Vajrasattva.

So here we can see that these first three practices of prostration, offering, and confession are actually building on earlier practices in the ngöndro. And returning to the grocery store example, as you shop, perhaps you could consider being mindful of your choices and their impacts. If you find yourself gravitating towards excessive or unhealthy or environmentally harmful products, you can acknowledge this internally and use that moment of awareness to commit to making better choices, whatever that means for you — whether that’s buying less or choosing more sustainable options, or simply being more conscious of your consumption habits or even your own health.

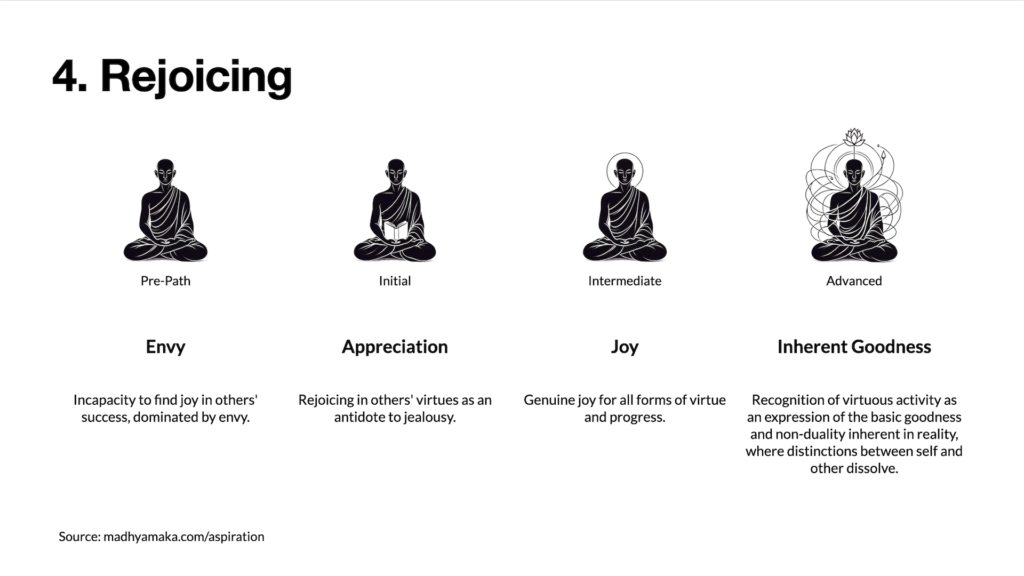

4. Rejoicing (verse 9)

Next we turn to the fourth branch, which is rejoicing or joyful praise. This involves rejoicing in the virtuous deeds and qualities of the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and all sentient beings. It’s a practice to cultivate positive mental states, counteracting envy and jealousy. This is also one verse:

1.4. Rejoicing

[9] With a heart full of delight, I rejoice at all the merits

Of buddhas and bodhisattvas,

Pratyekabuddhas, those in training and the arhats beyond training,

And every living being, throughout the entire universe.

So here, as Rinpoche said, it’s like we’re getting so excited about the qualities of all the Buddhas. As he explained, “In a mundane way of putting it, rejoicing is about getting excited about others who are having a good time and having good qualities”. So here we rejoice at the incredible qualities of the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Shravakas, Pratyekabuddhas, all the different enlightened beings on different vehicles of Buddhism. And not only them, we rejoice at all beings who have sublime or ordinary virtues and good qualities. We’re really happy that such qualities exist. We are not envious. We are not jealous. We don’t feel competitive. As Rinpoche said, “We almost feel relief that there are guys out there with such great qualities. Ah, now we can relax a bit because there’s someone who can take care of us, take care of the world. There’s someone who knows what they’re doing. The world is not that lost”. I think many of us in our current world can at times feel despair when we look at leaders in politics and business. And I know many young people in particular feel that leaders are not focused on what really matters to them. So where we see good examples, even in the ordinary world, that’s really something to celebrate.

Rinpoche notes that even non-Buddhists have practices of offering prostrations, making offerings and praise, and so forth. But rejoicing seems to be unique to Buddhism, especially the Mahayana path. And here we’re rejoicing in both the cause and the effect. So the effect, for example, when you see someone who is beautiful, handsome, and kind, enjoying the result that arises from positive causes, then you rejoice in that. Now, of course, that’s a very mediocre or general form of rejoicing. A much greater way of rejoicing is to rejoice in the cause and effect that is accomplished or created by Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. In other words, the causes of merit and the action of creating merit of all beings.

In the grocery store example, you might take a moment to feel joy for the abundance available to you and for the successes of others who’ve been involved in this chain of supply. This could be as simple as appreciating the variety of food or being happy for the local farmers whose products are featured in the store. Recognising and celebrating these positive aspects can help counter envy and competitiveness.

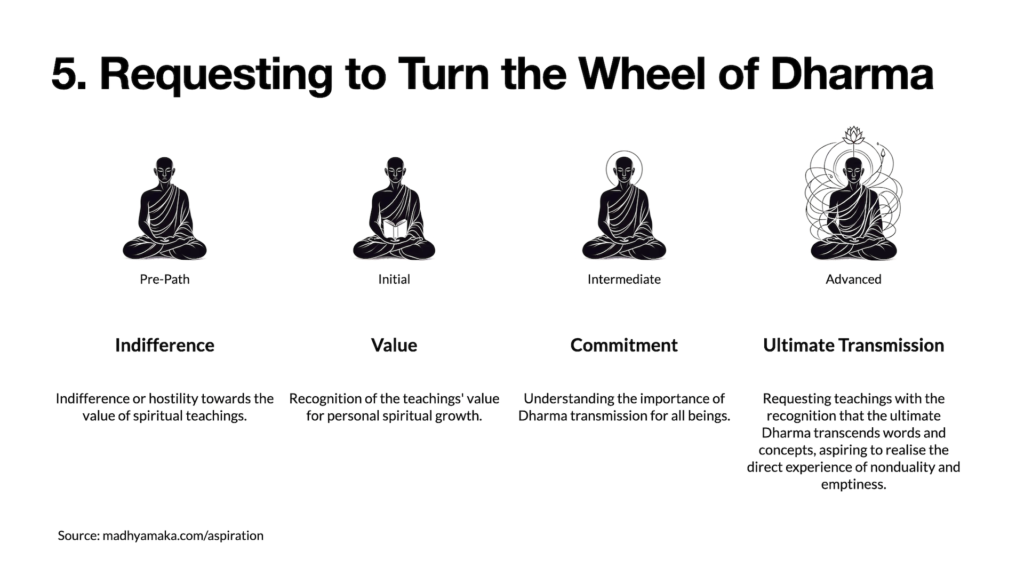

5. Imploring the Buddhas to turn the Wheel of Dharma (verse 10)

The fifth branch is requesting enlightened beings to turn the Wheel of Dharma. And here we’re requesting that the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas continue teaching the Dharma, ensuring that the teachings are available for the benefit of all beings, thus preventing the Dharma from fading away in this world:

1.5. Imploring the Buddhas to Turn the Wheel of Dharma

[10] You who are like beacons of light shining through the worlds,

Who passed through the stages of enlightenment, to attain buddhahood, freedom from all attachment,

I exhort you: all of you protectors,

Turn the unsurpassable wheel of Dharma.

Here, as Rinpoche said, we’re supplicating all of the Buddhas who are the real illuminators of this world that is filled with darkness. And we’re requesting them to teach, but also to point out our mistakes, to lead us to the right path, to answer our questions, to clear our doubt, to increase our enthusiasm and generate our confidence towards the spiritual path. Here, I really like this idea that “turning the wheel of the Dharma” is much more than just going through a text, and it really encompasses all the ways that someone can engage with us as a mitra, as a spiritual friend, helping to point out our mistakes, inspiring us, and increasing our confidence in the path — something much more holistic.

And so in that context, it might also be helpful for us to reflect once again on how we approach the Dharma, how we listen to the teachings. And going back to the Words of My Perfect Teacher, there’s the nice example of the three defects of a pot. So imagine you would like to fill a pot with water. The first defect is if you simply don’t listen or if you get distracted, that’s like having a pot that is turned upside down. You can’t begin to fill it with water. The second example is having a pot with a hole in it. No matter how many teachings you might hear, you’ll never retain them or assimilate them or put them into practice. And the third example is a pot with poison in it. So this is about mixing negative emotions or defilements or ego with what you’re hearing. That would be listening to the Dharma with an unhelpful motivation, perhaps with a desire to become great or famous, or tainted with others of the five poisons. In this case the Dharma will not only fail to help your mind, it will also be changed into something that is not Dharma at all, like nectar being poured into a pot containing poison. For example, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche spoke a lot about spiritual materialism and how we take Dharma as an adornment for our ego rather than as a means for purifying our ego. So let us challenge ourselves and be honest with ourselves: how are we listening to the teachings? What is our attitude?

Another of my favourite stories is from the Zen tradition, the story “A Cup of Tea”:

Nan-in received a university professor who came to inquire about Zen.

Nan-in served tea. He poured his visitor’s cup full, and then kept on pouring.

The professor watched the overflow until he no longer could restrain himself. “It is overfull. No more will go in!”

“Like this cup,” Nan-in said, “you are full of your own opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?”

In the grocery store example, perhaps we might turn this fifth branch into a wish or hope for the continued education and awareness of us and all consumers around healthy and ethical consumption. While we are shopping, it might mean favouring products from companies that engage in such educational efforts about nutrition or sustainability, thus supporting the spread of beneficial knowledge about how to shop and how to consume.

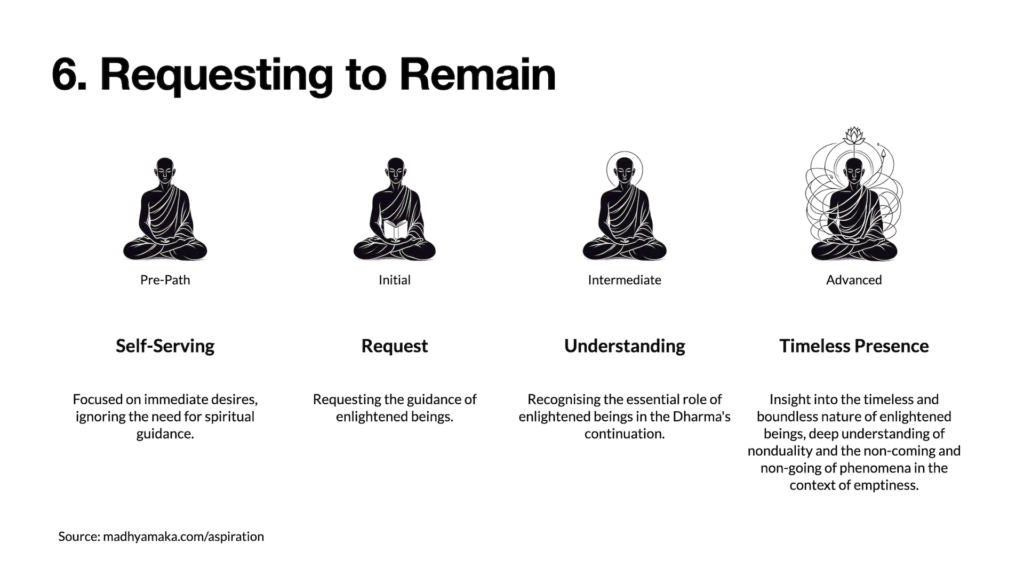

6. Requesting the Buddhas not to enter nirvana (verse 11)

The sixth branch is requesting to remain. Here we are urging the enlightened beings to remain in the world and not enter final nirvana, so they can continue to assist beings in their spiritual journeys:

1.6. Requesting the Buddhas not to Enter Nirvana

[11] Joining my palms together, I pray

To you who intend to pass into nirvana,

Remain, for aeons as many as the atoms in this world,

And bring well-being and happiness to all living beings.

Here Rinpoche said, “If there are Buddhas and Bodhisattvas who might wish to, how should I put it, conclude their display of benefiting sentient beings, in other words, those who might wish to pass into parinirvana, then urgently, in haste, we ask them not to do that”. We say, yes, we’re slow, we’re stupid. We may not learn right away, but have compassion. Bear with us. Please live long, if necessary, live for eons and eons.

So perhaps in the grocery store example, we might encourage the presence of goodness in the world by supporting ethical practices, choosing products from companies that treat workers well, or use sustainable farming practices or actively work towards positive social impacts, whatever good might mean to us in that relative way. And understanding that through our choices, our aspirations, we can encourage these good forces to remain and expand in the marketplace and in the outer world.

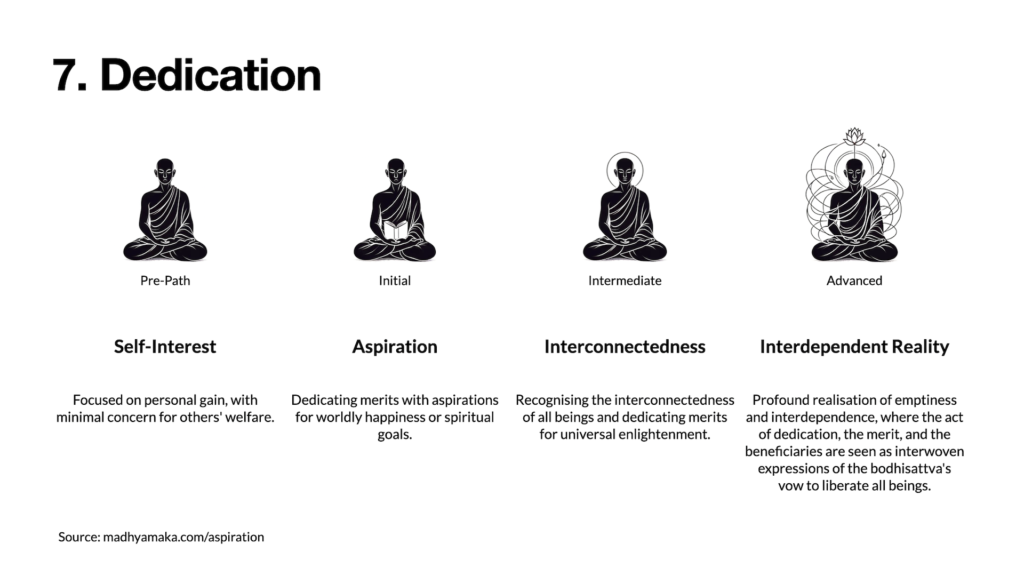

7. Dedication (verse 12)

The seventh branch is dedication, where we dedicate the merits accumulated from these initial practices for the enlightenment of all beings. This reflects the Mahayana principle of bodhichitta, aiming for the ultimate liberation of every sentient being from suffering:

1.7. Dedication

[12] What little virtue I have gathered through my homage,

Through offering, confession, and rejoicing,

Through exhortation and prayer—all of it

I dedicate to the enlightenment of all beings!

As Rinpoche said, “This is the standard painless but incredible and powerful Mahayana technique to accumulate merit”. Through this, we’re setting the foundation for our subsequent aspiration. We’ve generated merit or ability to do things. We now have the ability to aspire. So we’re going to dedicate this merit. We will dedicate the whole prayer at the very end, in verses 55 to 60, which we’ll come to in Week 8. But here we already wish to dedicate what we’ve done in these preliminary verses. We can’t dedicate enough — it’s a complete practice on its own.

Perhaps in the shopping trip example, you might conclude with a silent dedication of the merit of your actions, like choosing sustainable products or buying things in order to offer to a friend or to make donations. And you dedicate all this to the benefit of others. You might hope that your actions contribute to a healthy, happy world, dedicating the benefits of your mindful shopping to all being.

The three poisons

So we have completed the first twelve verses that comprise the Seven Branch Offering. I also wanted to talk a little about how these different branches of the Seven Branch Offering are also serving or functioning as antidotes to specific emotions or defilements. A lot of the questions that come up from practitioners have a lot to do with our experience or our emotions on the path. This can include our experiences or emotions as we’re engaging in practice, or as we are engaging in the world in our post-meditation — whether it’s in our relationships, in our family, in our work, or just looking at what’s going on in the outer world. So this is all to do with our emotions and therefore with defilements.

An introduction to the three poisons

Traditionally in Buddhism, we talk of three poisons, which are three afflictions or character flaws that are the root of craving, and thus in part the cause of dukkha — suffering, pain, unsatisfactoriness — and also of rebirths. And they’re symbolically drawn as three animals chasing after each other at the centre of the Buddhist Bhavachakra, the wheel of life artwork. So these three are:

- Passion (also termed attachment, greed, avarice or lust), which is represented by the rooster.

- Aggression (also anger, hatred or ill will), which is represented by the snake.

- Ignorance (also delusion or confusion), which is represented by the pig.

We can also see these as the three basic ways of relating to anything we consider to be an object or a phenomenon, whether it’s an object or person or phenomenon in the external world, or something in the inner world of our own mind and emotion. So those three ways are:

- I like it – when we like something, we pull it towards us. We want more of it. This is the poison of passion or attachment.

- I don’t like it – I want to push it away, to get rid of it. This is the poison of aggression or anger.

- I don’t care – maybe I think it’s irrelevant, maybe I don’t even notice it. This is the poison of ignorance.

These three poisons can also be turned inwards, towards our own thoughts, our own emotions, our own self, our own life. And when we do that, that can have significantly negative effects on our own mental health, our self-perception, and our overall well-being. They can contribute to cycles of self-criticism, guilt, low self-esteem, and other painful mental states. And this is, of course, very relevant with the mental health crisis we’re seeing in the world today, especially post-COVID, and especially amongst younger people. A lot has been written about the influence of social media and the issues of living a life online, and what how that is negatively impacting people in terms of anxiety, depression, self-criticism, and so forth.

We can also understand these three poisons through the lens of evolutionary psychology. You may have come across Robert Wright’s book, “Why Buddhism is True”, where he talks about Buddhism through the lens of evolutionary psychology, which is all about the ways in which our psychological traits, such as our emotions and thoughts and behaviours, have been shaped by natural selection. And from this perspective, our responses to the environment — including other people or events outside us, and also our own internal experiences and our own inner environment — can be understood as adaptations that at some point in our evolutionary history increased our ancestors’ chances of survival and reproduction. But nowadays, these adaptations can sometimes work against our well-being in modern contexts. So let me briefly talk about the three poisons through these lenses.

1. Passion

First, let’s look at passion, which includes attachment, greed, lust. The evolutionary perspective would be that the drive towards attachment and the pursuit of pleasurable experiences like food, sex, or social status can be understood as mechanisms that once ensured survival and reproductive success. For example, the desire for high-calorie foods and sexual partners at one point was very important in contributing to the survival of our ancestors’ genes. A Buddhist perspective would be that while natural and often enjoyable, attachment can lead to suffering when we cling to impermanent objects or experiences, then leading to disappointment, loss, and a cycle of continuous craving and addiction. We can integrate these views by understanding that our attachments are often amplified by our evolutionary predispositions. And that can help us understand and gradually loosen the grip of these desires, perhaps finding contentment in simpler pleasures and deeper connections that are not solely based on instinctual drives.

And if we think about how these might be turned inward, internalised passion can manifest as attachment to certain self-images, identities, or internal narratives that we believe are essential for our happiness or self-worth. It can include narcissism, an obsession with self-improvement, even to the point of never feeling good enough, a relentless pursuit of perfection, or clinging to past versions of ourselves that no longer serve us. Maybe we feel unworthy if we don’t constantly achieve success. Maybe we attach our self-esteem to external validation or accomplishments, or become preoccupied with maintaining a certain image or identity, even when it causes us distress. So all of these are ways of understanding how this poison can show up in our ordinary life.

2. Aggression

The second is aggression, which is also anger or hatred. From an evolutionary perspective, aggression can be seen as a protective mechanism, helping our ancestors defend against threats and compete successfully for resources. And this response to perceived threats was crucial for survival in a more dangerous, resource-scarce environment. A Buddhist perspective would be that while necessary for protection, habitual anger and hatred cause personal suffering and harm to others. These emotions cloud our judgment and lead to destructive actions and a cycle of retaliation. So if we understand that anger and hatred are evolutionary responses to threats, we can pause and ask ourselves whether an aggressive reaction is proportionate to the situation. Practices like mindfulness and compassion can help us respond to conflicts with wisdom rather than instinctive aggression.

Turned inwards, aggression can often appear as self-criticism, guilt, self-hatred. This internal aggression can be very punishing, holding ourselves to unrealistic standards, berating ourselves for perceived failures or shortcomings, also manifesting as guilt that goes beyond healthy remorse, becoming a pervasive sense of being fundamentally flawed and unworthy of happiness. Many of us, especially in the era of social media, engage in this kind of negative self-assessment or self-criticism. We might engage in harsh self-talk, constantly feeling guilty for not meeting our self-imposed or societal standards, or experiencing intense feelings of self-loathing for our mistakes or our human imperfections.

3. Ignorance

The third is ignorance or delusion and confusion. From an evolutionary perspective, ignorance in the form of not noticing or caring about certain stimuli can be an adaptive response to information overload, allowing our ancestors to focus on what was most relevant to survival and reproduction. However, of course, this can also lead to a lack of awareness about important aspects of our environment and inner lives. From a Buddhist perspective, ignorance is the fundamental poison, the misperception of the nature of reality or truth, particularly the belief in the permanent self and the inherent existence of phenomena. And this misperception is seen as the root of all other suffering. So we could perhaps integrate these ideas by recognising that our tendency to ignore or be indifferent to things that don’t immediately seem relevant can sometimes be helpful in helping us focus, but that we can also cultivate mindfulness and awareness to check whether we’re making the right choices. We can turn towards things we might otherwise ignore or reject. We can begin to perceive the interconnectedness of all things and the impermanent nature of our experiences and thereby align our awareness more closely with reality. So in this way, we’re practising both shamatha, learning to be non-distracted and learning to turn towards reality as it is, but also Vipassana, learning to see things more accurately, more truthfully.

Ignorance turned inwards manifests as a lack of self-awareness, a misunderstanding of our true nature, an unwillingness to see who we are. But it can also involve underestimating our potential, doubting our intrinsic worth or harbouring misperceptions about our abilities and limitations. We can be disconnected or not pay attention to our feelings, our needs, and our aspirations, and we can live in ways that don’t align with our true value or purposes. Now, especially as Dharma practitioners, to the extent that we have that kind of inner disconnection from our true aspiration, that’s a gap that it will really help us to begin to close — which is very much an underlying theme of the Pranidhana-Raja.

Defilements and antidotes

In different Buddhist traditions or teachings, there are many different ways of talking about or enumerating the various emotions and defilements. The Abhidharmakosha or “The Treasury of Abhidharma” was a systematic account written by the Indian pandita Vasubandhu in the fourth or fifth century CE, and it is considered the peak of scholarship in the Theravada vehicle. And it lists six root defilements. These include the three poisons we’ve already discussed — ignorance, attachment, anger — and also pride, doubt and wrong views.

Another way of thinking about the defilements is one that’s often seen in the Vajrayana, where we talk about five Buddha families and their associated five wisdoms, which are purified version of five poisons. So here we have the three poisons — ignorance, attachment, anger — and also pride and jealousy. The correspondence with the Buddha families is as follows:

- Ignorance = Buddha family (Vairochana: transformation from Ignorance to Dharmadhatu Wisdom)

- Aggression/Anger = Vajra family (Akshobhya: transformation from Anger to Mirror-like Wisdom)

- Greed/pride = Ratna family (Ratnasambhava: transformation from Pride to Equanimity)

- Passion/Lust = Padma family (Amitabha: transformation from Attachment to Discriminating Wisdom)

- Envy/Jealousy = Karma family (Amoghasiddhi: transformation from Jealousy to All-Accomplishing Wisdom)

In different commentaries, there are many different ways that this Seven Branch Offering is explained as counteracting the various poisons. I’m going to use the approach from Chökyi Drakpa, a Tibetan master who wrote the ngöndro commentary “A Torch for the Path to Omniscience”, who describes the defilements and antidotes provided by the seven branches as follows:

1) Prostration is the antidote to pride. Pride is the overinflated sense of self-importance and superiority over others. It’s a barrier to our learning and growth because it closes our mind to the wisdom of others. Prostration counteracts pride by cultivating humility and reverence. By physically bowing down and mentally paying homage to the Buddhas and enlightened beings, we acknowledge their qualities and their achievements, and thereby dissolve the ego’s hold and open our hearts to learning and developing compassion.

2) Offering is the antidote to avarice or greed. That is the intense and selfish desire for wealth, resources, possessions, fame or status, and it comes from attachment, and of course leads to suffering. Offering involves giving away something valuable, either symbolically or actually, which counteracts our greed by cultivating non-attachment. The practice of mandala offering, where the universe and all of its treasures are envisioned as being offered, helps to loosen the grip of material attachment and develop a mind of abundance and also joy in giving.

3) Confession is the antidote to aggression. Aggression, anger, and hatred come from aversion. These are destructive emotions that obscure our mind, and prevent the cultivation of peace and compassion. Confession involves acknowledging and purifying our own negative deeds, especially those driven by aggression or anger, which are often said in the teachings to be the strongest of all negative deeds. Reciting the Vajrasattva mantra or visualising purification can transform the energy of aggression into wisdom and clarity, facilitating profound inner peace.

4) Rejoicing is the antidote to jealousy. Jealousy is the resentment towards others’ success or happiness. It’s a source of very unnecessary suffering stemming from comparison and competition. So by rejoicing in the virtues and accomplishments of others, we can counteract jealousy, cultivating genuine happiness for others’ success. It transforms our mind of comparison and contrasting into one of appreciation and interconnected joy, undermining the isolating effects of jealousy.

5) Requesting to turn the Wheel of Dharma is the antidote to ignorance. In the Buddhist context, as we have seen, ignorance refers to the fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of reality, especially the nature of emptiness and interdependence. And by requesting the Buddhas and enlightened masters to turn the wheel of the Dharma, we’re aspiring for the continued presence of the teachings, recognising their value in dispelling our ignorance. This fifth branch affirms the importance of wisdom and learning in overcoming ignorance and fosters our own commitment to the path of enlightenment.

6) Requesting the enlightened ones not to pass into parinirvana is the antidote to wrong views. These wrong views include misconceptions about the nature of reality, about what is ethical conduct, how to follow the path to liberation, and all the obstacles that are getting in the way of our understanding and practicing the Dharma correctly. So this plea for the enlightened ones to remain is to ask them to guide beings, emphasise the value of correct teachings, maintaining our correct understanding and practice of Dharma, as Rinpoche explained earlier.

7) Dedication is the antidote to doubt. Doubt includes uncertainty or skepticism about the teachings or one’s practice, or about the path to enlightenment. This can paralyse or prevent our practice, and really get in the way of our progress on the path. So dedication is about offering the positive energy that we have accumulated through our practice to the benefit of all beings, as we’ve seen. And it counteracts doubts by reinforcing the efficacy and the purpose of our practice, connecting our personal progress to the broader aspiration for universal enlightenment, thereby helping us solidify our confidence and faith in the path and the interconnectedness of all efforts towards liberation. We will talk about dedication more in future weeks, especially Week 8.

Understanding emptiness

Practicing the paramitas

I would like to say just a few things about emptiness and inconceivability, even though we are only in these early verses that are still generating the merit and setting the stage for what is to come. We’re going to come to this in more depth and more detail in future weeks. But at this stage, it’s already useful to think about how might we approach or think about emptiness or inconceivability in these early verses, not least because of how the verses themselves have introduced this topic directly with their descriptions of time, space and quantity.

In the Bodhisattva Path, we talk about the practice of the paramitas or “perfections”. There are typically six: generosity, discipline, patience, diligence, meditation, and wisdom. The concept of a Paramita represents a perfection or transcendent quality that Bodhisattvas are cultivating on the path to enlightenment so that they can better act with wisdom and compassion for the benefit of all sentient beings. The term “paramita” literally means “gone to the other shore”, where “para” means “to the other shore” and “mita” means “gone”. So it indicates a crossing over from the shore of samsara or cyclic existence to the shore of nirvana or liberation. The sutras also give the analogy of the Buddha being a boatman who takes us across the river, from one shore to the other. And this transformation is not just a quantitative change, but a qualitative shift in how we practice these virtuous qualities. So for example, to cultivate the paramita of generosity, we build on and extend the ordinary practice of generosity that we are familiar with in our everyday life. We are going beyond an ordinary generosity in four different ways — in terms of intention, wisdom, scope, and nature.

- Intention: In ordinary generosity, our acts of giving often come with expectations of gratitude or recognition, or perhaps a favourable outcome for ourselves. And while our motivation may be positive, it may be still rooted in a self-centred desire or expectation of a reciprocal benefit. Whereas the paramita of generosity is characterised by a purely altruistic intention to benefit others, without any expectation of reward or recognition. Our primary motivation is bodhichitta, aspiring to achieve enlightenment for the welfare of others and ultimately for all sentient beings to attain enlightenment.

- Wisdom: Ordinary generosity might not always be informed by deep understanding of the recipient’s needs or the long-term consequences of our gift. The act is often driven by immediate circumstances or our emotional responses. Whereas generosity at the level of a paramita is practiced with wisdom and discernment, which means understanding the most beneficial way to give, what to give, when to give, and to whom, so that our acts of giving truly benefit the recipient. This wisdom is rooted in an understanding of emptiness, seeing beyond the conventional notions of giver, gift, and recipient, and recognising the interdependent nature of all phenomena. At its most fully developed, generosity is an expression of non-dual wisdom.

- Scope: In terms of scope, ordinary generosity is usually limited. We are thinking of a relatively small number of beings, often directly confined to those within our immediate circle or community. Whereas the paramita of generosity has a boundless scope, aiming to benefit all beings without discrimination. The practitioner of generosity seeks to freely give without bias or prejudice, including giving material aid, protection from fear, and sharing the Dharma.

- Nature: Ordinarily, our gifts might be material or worldly benefits, which while valuable, offer temporary relief or temporary happiness. With the Paramita of generosity, while material gifts are not excluded, we want to encompass non-material gifts as well, such as fearlessness, love, and ultimately the gift of Dharma. The highest form of generosity is considered sharing the teachings that lead to liberation.

So in essence, the transition from ordinary practices to their paramita counterparts involves a profound deepening of our motivation, an expansion of wisdom, and an extension of the scope of these virtues. The practice of these paramitas is what sets the Bodhisattva path apart from ordinary good deeds, aiming not just for personal liberation, but for the enlightenment of all beings, driven by profound compassion and informed by the wisdom of emptiness.. When we think about our practice of the King of Aspiration Prayers, it can be helpful if we think about the nature of what it means to engage in a paramita. I encourage you to bear that in mind.

Integrating emptiness as we progress on the path

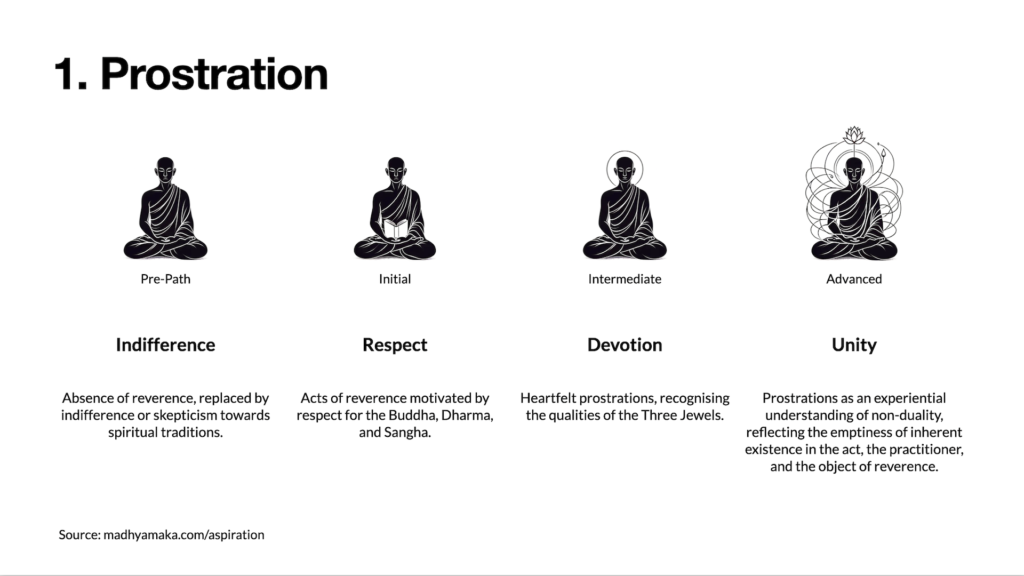

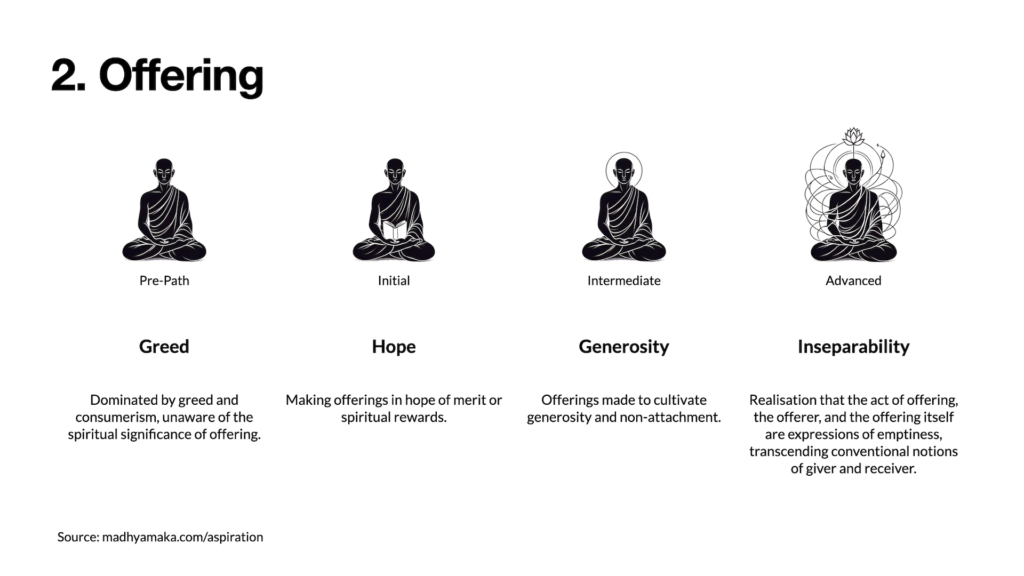

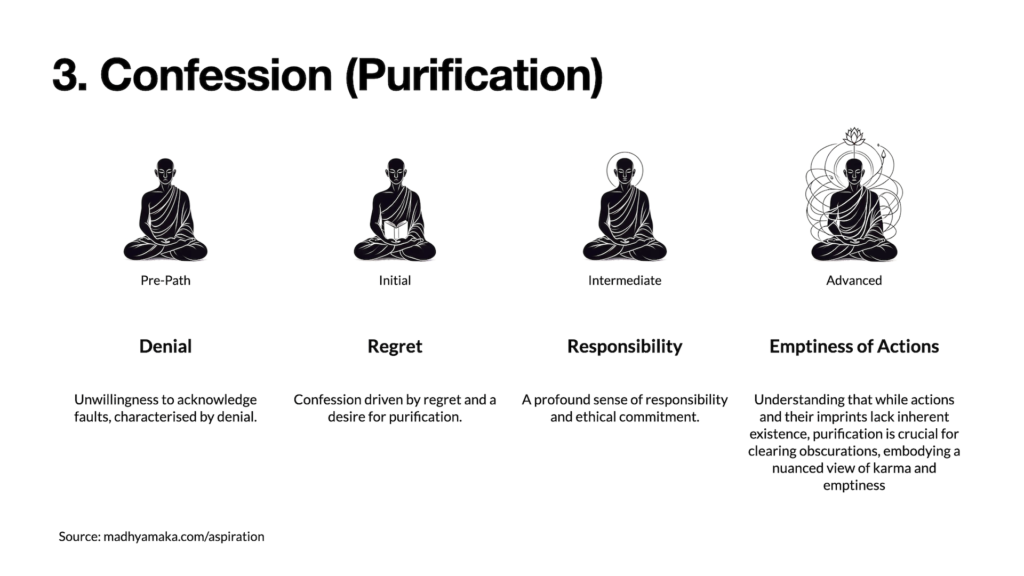

To help us think about how might we integrate the view and practice of emptiness and nonduality into the Seven Branch Offering, I’ve put together some slides to illustrate how we might typically progress on our path, from beginners to more advanced practitioners who are able to integrate a realisation of emptiness in our practice and in our path. I’ve chosen to focus on the same four stages for each of the seven branches:

- Pre-path: The starting point is ordinary deluded sentient beings who haven’t yet started a spiritual practice. At this stage, our way of life is typically marked by confusion, self-centredness and distraction. Our view is characterised by fundamental misunderstandings about the nature of self, others, and reality. We are still rooted in dualism and materialism, with little to no insight into the interconnected and impermanent nature of phenomena. Our mind is easily distracted and dominated by discursive thought and harmful emotions, with little awareness of the present moment or control over mental processes. Our actions are primarily driven by self-interest, with ethical considerations often subordinate to personal gain or pleasure.

- Initial: During the initial stage of practice, we begin to have early experiences and glimpses of understanding and realisation, and we solidify and clarify our understanding and our view. Although our understanding is primarily conceptual, we are beginning to grasp the concepts of impermanence, suffering, and non-self intellectually. We develop basic concentration and mindfulness skills, enabling us to stabilise the mind and become more consistently present. In our behaviour, we are increasingly taking accountability for our words and actions, and we are motivated by the desire to avoid causing harm and to be of benefit to oneself and others.

- Intermediate: In the intermediate stage, our understanding becomes a real lived experience, much more integrated with our emotions, as well as our intellectual understanding. Deepening contemplation leads to a more personal, reflective insight about the meaning and application of the teachings. We start to notice the direct implications of impermanence, suffering, and non-self in our life, leading to a transformation in perception and experience. Our meditation practice deepens, leading to the integration of meditative awareness into daily life. Moments of calm and insight become more frequent, indicating a growing harmony between meditative practice and everyday activities. Our behaviour becomes increasingly motivated by compassion and the wish to benefit others. We begin to naturally avoid harmful actions and engage in positive activities, recognising their impact on the well-being of all beings.

- Advanced: Finally, as more advanced practitioners, we have a more integrated or unified practice, where our view is well established and non-duality and emptiness are really infusing our practice. The intellectual and reflective understanding matures into a direct experiential realisation of emptiness and nonduality. Wisdom permeates all aspects of life, and we see through the illusion of inherent existence and recognise the interdependent origination of all phenomena. The distinction between meditation and non-meditation dissolves, as we abide in a continuous state of awareness that transcends dualistic distinctions between subject and object, activity and rest. This non-dual awareness is the natural state, unconstructed and effortlessly present. Ethical conduct arises spontaneously, without contrivance or effort, as a natural expression of enlightened awareness. Our actions are perfectly attuned to the needs of the moment, embodying the union of wisdom and compassion.

So let’s consider the seven branches in terms of these four stages, starting with prostration (Note: please click on the slides to see them full size):

Through the practice of the Seven Branch Offering, practitioners cultivate a deepening awareness and realisation of the Dharma, moving from engaging in these practices as external acts to embodying their essence in the realisation of nondual wisdom.

Application to sangha

In closing, I’d like to reflect a little about how we might practice this in the context of our relationships, and especially in the context of the sangha, our spiritual community. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche has talked a lot in recent years about how Christians especially do a really good job in creating very vibrant and caring spiritual communities that emphasise kindness and care and help. And he’s encouraged us as buddhists to do more within our own communities, welcoming and including newcomers and caring for each other, and also treating our sangha relationships as a field of practice for our own cultivation of bodhichitta. Bringing our practice of the Seven Branch Offering to our sangha relationships is then not only for our own benefit, but to strengthen and uplift the community as a whole.

- Prostration: In the relative or material sense, prostration could mean showing respect and kindness to others in the sangha, recognising their commitment to the path. This could be as simple as greeting them warmly, listening attentively when they speak, or showing appreciation for their practice and contributions. A more non-dual or emptiness-oriented approach might be to cultivate the understanding that the act of showing respect is not just about social niceties, but is a recognition of the Buddhanature inherent in every person. In this way, our reverence is not dependent on hierarchical status or how long someone might have been practicing Dharma, but a recognition of our shared and universal potential for enlightenment.

- Offering: Relatively, we can offer help and support to sangha members, whether through sharing resources, emotional support or volunteering for community tasks. Acts of service and generosity strengthen our bonds and purify our own avarice and greed. From an emptiness perspective, we can make offerings without attachment to the self who offers, or the expectation of gratitude. We can understand these acts of generosity are expressions of interconnectedness, reflecting the practice of giving at a deeper, more profound level.

- Confession: Relatively, when there are conflicts or misunderstandings in the sangha with our friends and colleagues, we can take responsibility for our part. We can apologise and we can seek reconciliation as practical applications of this third branch. More ultimately, we can reflect that the nature of mistakes and conflicts arises from a web of conditions and lacks inherent existence. This practice can foster a more compassionate approach to resolving difficulties, one not fixated on blame but focused on mutual growth and deeper understanding.

- Rejoicing: Relatively, we can actively celebrate the achievements and virtues of sangha members. We can encourage and support each other’s practice and accomplishments, and thereby foster a positive and uplifting environment. More ultimately, we can rejoice with the understanding that these virtues and achievements are the manifestations of the same ultimate nature that we all share, dissolving any sense of separation or competition.

- Requesting to turn the Wheel of Dharma: Relatively, we encourage the sharing of teachings and insights within the sangha, and request teachings from those more experienced, or share our own insights when appropriate, to improve collective understanding. From an emptiness or non-dual perspective, we approach the requesting and sharing of dharma with the recognition that teachings transcend individual perspectives, pointing to a shared reality beyond words and concepts.

- Requesting to remain: Relatively, this could include encouraging and supporting sangha members to continue with their practice, especially in times of doubt or difficulty. Our encouragement can be a crucial support for others. Ultimately, recognising that encouragement to persist in practice is an affirmation of the non-dual truth that underlies our experiences, urging each other to realise and embody this truth fully.

- Dedication: Relatively, we dedicate the merits of our practice and achievements to the well-being and enlightenment of all members of the sangha, and beyond. We share success in this way to multiply its positive impact. More ultimately, we understand that dedication is an expression of the interdependent nature of existence. By dedicating merit, we acknowledge that no achievement is personal or isolated. It is a wave in the ocean of collective existence.

With this, let us take a moment to dedicate whatever merit we might have generated today, and dedicate it to the enlightenment of all sentient beings.

[END OF TEACHING]

Note: to read footnotes please click on superscript numbers

Transcribed and edited by Alex Li Trisoglio