Alex Li Trisoglio

Aspiration: Week 5 – Perseverance

April 13, 2024

56 minutes

Reference: Samantabhadra’s King of Aspiration Prayers, verses 22 – 27

Introduction to Week 5

Welcome

Hello and welcome to Week 5 of our review of Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s teachings on Samantabhadra’s King of Aspiration Prayers, the Pranidhana-Raja. In this week’s image we see a solitary figure of a practitioner walking on a path through difficult and unforgiving terrain. There’s a mountain ahead, majestic yet daunting, which represents their ultimate aim, perhaps enlightenment itself. The journey is not for the faint of heart. It is a path fraught with obstacles. Yet it is the very challenge of the climb that strengthens our spirit. How many times have we found ourselves on a similar path in our lives, where the goal seems distant and the road arduous?

As we begin Week 5, let us reflect on this image. What does the mountain ahead symbolise for you in your practice? How does the figure’s steady progress, step by step, resonate with your own journey? And most importantly, when the path becomes steep and the footing uncertain, what is it that propels us forward? We’re going to explore the deep reserves of perseverance that lie within us and discover how to harness them, just as the practitioner in this image does, with unwavering focus on the path ahead.

So as usual, let’s just take a moment to tune our motivation for this week, reminding ourselves that we wish to approach our time together with bodhichitta, the aspiration that we might attain enlightenment for the sake of enlightening all beings.

[Pause]

Key themes

The title for Week 5 is Perseverance, and the verses this week cover two, perhaps two and a half, key themes:

- 1) Handling challenges and setbacks on the path: We know that difficulties, setbacks and disappointments are an inevitable part of the bodhisattva path, indeed of any path where we’re trying to accomplish something meaningful and worthwhile. So how can the bodhisattva find a way to handle these challenges without getting discouraged and losing inspiration?

- 2) Relating to others on the path: We already started last week to explore the idea of how to be a spiritual friend, including Rinpoche’s lovely example of the YouTube bodhisattva. This week’s verses will go into this topic in more depth. How should the bodhisattva relate to others on the path, especially when they might appear to us to be the sources of some of the difficulties and challenges that we face?

- 3) Purifying our perception: This is a topic that’s going to become more important in future weeks, but already this week we are coming to verses that talk about seeing Buddhas and receiving teachings at all times. So how might we start to refine and purify our perception? We’re going to introduce this theme this week, but not go too deeply, which is why I’m saying perhaps we will cover two and a half themes.

Review of the stages of the path

In terms of the structure of the verses this week, let’s review where we’re at in the text. After an introduction in Week 1 and discussion of the benefits of reciting this prayer in Week 2, we went through the initial practices of the seven branch offering in Week 3 and started the actual aspiration last week in Week 4.

Last week we looked at how the practitioner progresses along the Mahayana journey when we talked about the Five Paths, and we started the verses of the Pranidhana-Raja that are focused on what Rinpoche called the “beginner bodhisattvas” of the first and second of these Five Paths. We’re going to conclude those verses today, and to help us understand the progression on the bodhisattva’s journey that we will cover in today’s verses, let’s talk about the First and Second Paths in a little more detail.

The First Path: The Path of Accumulation

The First Path, the Path of Accumulation, is about effortless motivation. We saw last week that the First Path begins when we wholeheartedly commit to the Mahayana path. We talked about crossing the threshold and taking the bodhisattva vow and we also acknowledged that there’s quite likely going to be a deepening in the sincerity and authenticity of our bodhisattva vow after we’ve taken the vow a hundred thousand times, for example, in our ngöndro practice.

In any case, the Mahayana teachings say that we attain the First Path (which is also translated as “the first pathway mind”), when we have attained “unlaboured bodhichitta” as our primary motivation in life. Here, “unlaboured” means that this mental factor arises without us needing to work ourselves up to it by relying step-by-step on a line of reasoning. In other words, it has become part of us. We no longer need to convince ourselves this is the right thing to do.

More fully, in the Theravada path, we attain the First Path when we attain unlaboured renunciation as our primary motivation in life. And in the Mahayana, we attain the First Path when we attain both unlaboured renunciation and also unlaboured bodhichitta. So it’s important to note that we don’t actually attain the First Path if we haven’t got this unlaboured renunciation as well. We haven’t spent much time talking about renunciation so far. And I know this can sometimes feel like a bit of a touchy topic for contemporary Buddhists, as many of us want to have our cake and eat it too. Yes, we would like all the inspiration and benefits of being practitioners of the Mahayana. But we also value our material comforts and personal fulfilment in our ordinary worldly lives. And for many of us, this creates an unresolved tension at the heart of our spiritual path. We’ll talk about this more in the later weeks.

Going back to the meaning of “unlaboured bodhichitta” as our primary motivation in life, this doesn’t necessarily mean that we are conscious or attentive of this motivation in every moment from that point onwards. Nor does it mean that we don’t have other short-term motivations, such as the motivation to go to the store and buy groceries. Nevertheless, even when we’re not consciously thinking about renunciation or bodhichitta, we still have the intention to achieve liberation and enlightenment and to benefit all sentient beings. We never lose that intention as our primary motivation in our lives, no matter what we do.

So to repeat, the First Path is defined by our primary motivation and aspiration, which is why for beginners like us, aspiration is considered the most important practice. Because genuine and unlaboured renunciation and bodhichitta are above all about transforming our motivation and aspiration from ordinary worldly aspirations to the grand Mahayana aspiration of bodhichitta.

And after we have reoriented our primary motivation, the rest of our path, right until enlightenment, is about cultivating wisdom through hearing, contemplation and meditation. As Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche often says, the Buddhist path is above all a path of wisdom. He also talks about it in terms of realising the truth. So let’s take a moment to understand what we mean when we say realising the truth. In both the Theravada and Mahayana paths, the main meditation object for Shravakas, Pratyekabuddhas and Bodhisattvas throughout all of the Five Paths are what is known as the 16 aspects of the Four Noble Truths. Now this is a large and somewhat technical topic, especially because anatta or non-self is defined somewhat differently in the Theravada and Mahayana traditions. However, let’s take the risk of oversimplification and say that during the Five Paths, what we’re doing is cultivating discriminating awareness and removing defilements and wrong views. In other words, we’re cultivating wisdom by meditating on the truth — the true nature of self and phenomena. And in the Mahayana, this means meditating on emptiness or shunyata, which we can also talk about in terms of meditating on non-dual wisdom or even meditating on the nature of mind.

Of course, before we can meditate on the truth, we need to learn a little bit about what it is that we’re supposed to be meditating on. So we will need to spend some time hearing and contemplating the teachings to better understand this truth, much of which will happen in parallel with our journey to cultivate a stronger and more genuine aspiration. And ideally the two will support each other. As we learn more, we’ll become more inspired about cultivating genuine aspiration to follow the path. And as our aspiration matures, we’ll become more inspired to deepen our understanding. So let’s go back to the Five Paths. As we proceed on the First Path, we achieve what’s known as shamatha focused on this truth or nature. In other words, we’re able to maintain a serenely stilled and settled state of mind, calm abiding, focused on the truth of emptiness of self and of all phenomena.

The Second Path: The Path of Joining

We transition to the Second Path, which is the Path of Joining or the Path of Preparation, when we attain an effortless understanding of the view. So this is about achieving not just shamatha, but both shamatha and vipassana focused conceptually on the truth (more fully, the 16 aspects of the Four Noble Truths). And thus we gain what is known as the “wisdom that arises from meditation”. In other words, we have both intellectual and meditative understanding of emptiness, although we don’t yet have direct realisation, which only comes on the Third Path, the Path of Seeing.

And in the same way that on the First Path, we attained unlaboured bodhichitta as our primary motivation, on the Second Path, we attain unlaboured certitude or conviction in our conceptual understanding of emptiness. We firmly establish the view of emptiness or non-duality, and it is now the primary way that we see the world. Now this may not sound especially significant, but according to the Mahayana teachings, it means we will no longer be reborn in any of the three lower realms — the hell, hungry ghost or animal realms. In other words, we’ll no longer be in the grip of strong negative emotions, especially anger.

It’s also worth noting that mindfulness alone is not the mark of progress on the Mahayana path, because even before the First Path, we may already have achieved samatha and vipassana focused on some other object, in other words, something other than the truth of emptiness. And in fact, this attainment is not exclusively Buddhist. Non-Buddhist meditators also practice and achieve samatha and vipassana, although not focused on the truth as identified in Buddhism, in other words, the emptiness of self and phenomena. And so this is why so much time is spent in Buddhist philosophy on establishing the truth and debating emptiness. We want to make sure that we have the correct object for our meditation — the right view that we’re trying to understand and realise — because otherwise we’re not even practicing according to the Buddhist path.

Also last week, we mentioned that Rinpoche likes to talk about enlightenment in terms of realising the truth. And we can now see that this is literally what the Mahayana teachings are saying, since the truth of emptiness, or more fully the 16 aspects of the Four Noble Truths, is our meditation object throughout the path until we attain enlightenment. From our early, more conceptual and dualistic practice of mindfulness and meditation, and remaining so as our practice progressively becomes more non-conceptual and non-dual.

The Third Path: The Path of Seeing

And then the Third Path, the Path of Seeing, is realisation of the view. That’s when we achieve both samatha and vipassana focused non-conceptually on the truth. In other words, when we have a direct, non-dual realisation of this truth. This is also known as yogic bare cognition. And we’re going to come to these verses next week in Week 6.

The sixteen aspirations in the Pranidhana-Raja

So in terms of the Actual Aspiration in the Pranidhana Raja, we have seen there are 16 aspirations. And the first 10 of these are those on the first and second of these Five Paths. So let’s review the progression.

- Aspirations #1 to #4: Last week in Week 4, we covered the first four of these aspirations, which are about aspiring to aspire well. We aspire to be able to authentically take Refuge and the Bodhisattva Vow, during which time we’re also engaging in hearing and contemplation to develop an intellectual understanding of emptiness. We’re also cultivating merit, so the aspiration of bodhichitta slowly but surely becomes our primary motivation in life.

- Aspirations #5 to #9: Now this week we’re going to cover the fifth to the tenth aspirations. And numbers five through nine are the First Path. Because by the fifth aspiration, which is verse 22, we have unlaboured renunciation and bodhichitta as our primary motivations in life. Now, the commentaries on the Pranidhana-Raja are not explicit about which verse refers to the attainment of the First Path, but by this stage, our aim is now clear. It doesn’t mean we don’t still experience difficulties on the path, which is why this week’s aspirations start with the fifth aspiration, which is “Wearing the armour of dedication”. There’s no question in our minds that we wish to keep going on this journey. So now we’re asking ourselves, how can we best deal with obstacles and ensure that we put in place the conditions for success? And since an important part of our bodhisattva aspiration and activity is engaging with other people, a significant focus of today’s verses is about our aspiration in relating to others. Of course we’re going to continue to cultivate merit and wisdom as we proceed on the First Path, so that our understanding and realisation of emptiness continues to deepen, and that we’ll be able to progress further on our bodhisattva journey and attain the Second Path.

- Aspiration #10: By the tenth aspiration in verse 27, which is the last of this week’s verses, we’re on the Second Path. Again, the commentaries are not explicit about where the transition occurs, but here the verse talks about how we’re aspiring to gather inexhaustible merit and wisdom, and so become an “inexhaustible treasury of noble qualities”. Although the verse notes that we’re still wandering through all the states of samsaric existence. So we’re on the Second Path. It’s the highest stage as ordinary samsaric beings, before we enter the Third Path, starting next week with the eleventh of the sixteen aspirations.

5. Aspiration to wear the armour of dedication (verse 22)

So let’s turn to the verses. Verse 22, which is the fifth aspiration, is the aspiration to wear the armour of dedication:

[22] I shall bring enlightened action to perfection,

Serve beings so as to suit their needs,

Teach them to accomplish Good Actions,

And continue this, throughout all the aeons to come!

Here Rinpoche explains this armour of bodhichitta in two different ways.

- (1) The armour of not losing inspiration on the path: First, he says it’s about not feeling exhausted or losing inspiration, not becoming lethargic, not becoming discouraged. He says the reason we get discouraged is because we’re not well versed in the Mahayana. We don’t have enough understanding of wisdom and method. There are many examples given in the commentaries. For example, one bodhisattva got so exhausted and discouraged because he felt the path was taking so long, and the Buddha gave him encouragement by saying that time is totally an illusion. Another story is of a mother who dreams that her only child is drowning in a river. The mother doesn’t think twice, and immediately she’ll jump into the river to save her child. But the bodhisattva, one who is adorned with wisdom, also knows this is just a dream.

- (2) The armour of serving beings to suit their needs: The second way we’re talking about the armour of bodhichitta is returning to the topic of fulfilling the wishes of all sentient beings by making our action or conduct harmonious to the actions of those sentient beings. We already talked about the YouTube bodhisattva last week. We aim to align our action and activities with other beings, and at the same time, we also need to engage in the good conduct of ensuring their happiness and their benefit. So as Rinpoche said, when you’re talking to someone else, you should understand their receptivity to what you’re saying, and what you say should be something they can hear, understand, and accept. As he said, bodhisattvas really don’t want to be some kind of thorny teacher that’s always correcting beings, saying things like “don’t do this, don’t do that”. It’s much more about them aspiring to be a friend rather than a corrector or an inspector.

In one of the commentaries on the Pranidhana-Raja by Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso, he explained that this set of verses 22 to 25, which is the fifth to the eighth aspirations, can also be understood in terms of how to behave towards people that we may regard as lesser, equal, or greater than ourselves in terms of merit and wisdom. So this fifth aspiration in verse 22 is about how to behave towards people we regard as lesser than ourselves in terms of merit and wisdom. For example, the might be in less fortunate circumstances, newer and less experienced in study and practice and so forth. And here, it’s key that we don’t look down on them with contempt. We don’t discourage them. We don’t belittle them. Because if we do that, it defeats the purpose of our aspiration to benefit them. So we’re careful to have good conduct and behave properly towards them, to encourage them, and to inspire them, as in the example of the YouTube Bodhisattva. Now, of course, this doesn’t mean that the way we see them as being lesser than us is accurate or correct. And indeed, as we progress in our cultivation of pure perception, we’ll realise that seeing anyone as lesser or impure is itself a form of ignorance.

(1) The armour of not losing inspiration on the path

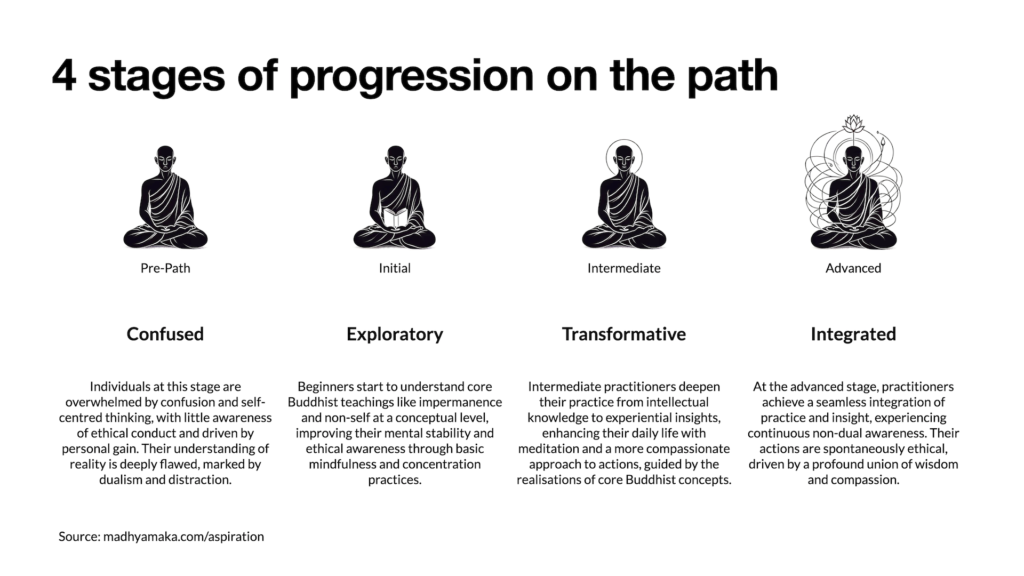

So let’s talk a little bit about this first idea of wearing the armour of bodhichitta in terms of handling the challenges that come up on the path. We’ll talk more about cultivating merit and wisdom to realise the view of emptiness starting next week. But given this week’s theme of perseverance and handling challenges, let’s look at how we might face and handle challenges, setbacks, and disappointments. And here, I’m going to use the same four stages on the path that we discussed in Week 3.

- Pre-path: Before embarking on the spiritual journey, we are characterised by confusion, self-centredness, and distraction. Our understanding of the self, others, and reality is fundamentally flawed, driven by dualism and materialism. Our mind is dominated by discursive thoughts and harmful emotions, with little presence in the moment or control over mental processes. Our actions are mostly driven by self-interest, with ethical considerations taking a back seat to personal gain or pleasure.

- Initial (Beginner): At this stage, we start to engage with spiritual practice and gain early insights into key Buddhist concepts like impermanence, suffering, and non-self, though primarily at a conceptual level. We develop basic skills in concentration and mindfulness, which help stabilise the mind and enable a more consistent presence in the moment. Ethically, there is a shift towards accountability for our actions, driven by a desire to avoid harm and benefit ourselves and others.

- Intermediate: Here, our understanding evolves from intellectual to experiential. Deep contemplation leads to reflective insights that make the teachings more personally relevant. The implications of impermanence, suffering, and non-self are directly observed, transforming our perception and experience. Our meditation practice deepens, integrating meditative awareness into daily life. Behavioural changes are motivated by a growing compassion and a desire to benefit others, with a natural avoidance of harmful actions and an engagement in positive activities.

- Advanced: In the advanced stage, our practice and understanding are highly integrated. We have a well-established view that incorporates non-duality and emptiness. Our intellectual and reflective understandings mature into direct realisations. Wisdom becomes pervasive in all aspects of our life, and we see through the illusion of inherent existence, recognising the interdependent origination of all phenomena. The line between meditation and non-meditation blurs, with continuous non-dual awareness becoming our natural state. Ethical conduct arises spontaneously as a natural expression of our enlightened awareness, perfectly attuned to the needs of the moment and embodying the union of wisdom and compassion.

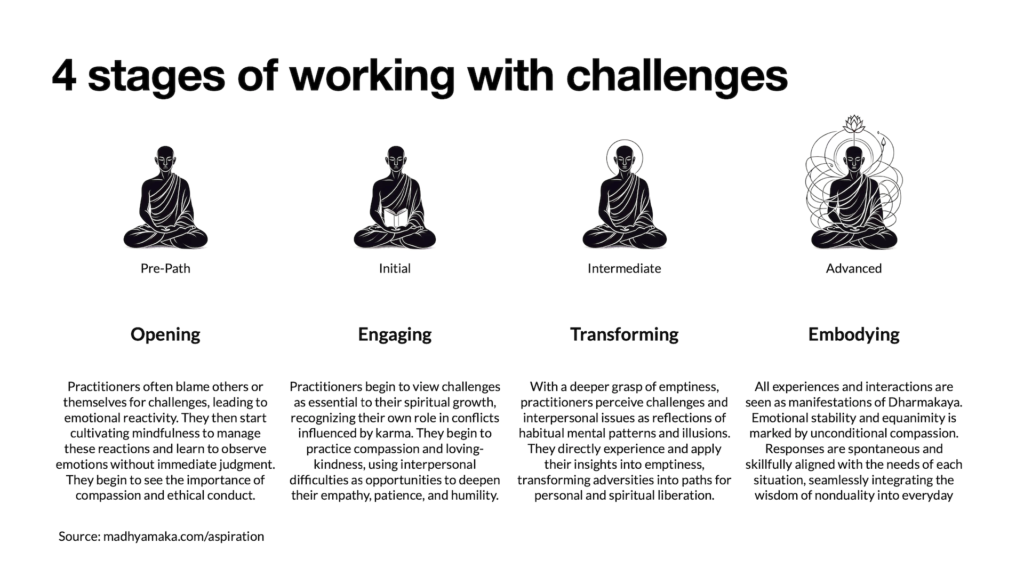

So how might we approach challenges and difficulties on the path, including difficulties with other people, as we progress on the path?

- Pre-path: In this stage, we attribute challenges and interpersonal conflicts to external factors or our own shortcomings, experiencing emotional reactivity and self-criticism. We begin to read or listen to the teachings, and we develop a foundational mindfulness practice to manage our reactions, learning to observe emotions without immediate identification and starting to grasp the concepts of impermanence and karma. This stage sets the groundwork for recognising the need for a more compassionate and ethical approach to life’s difficulties.

- Initial (Beginner): At this stage, we develop a foundational understanding of Dharma, beginning to view challenges as integral to our spiritual growth. We recognise the role of karma and habits in shaping our experiences and we start practicing compassion and loving-kindness. Through our practices we aspire to foster empathy and a genuine concern for the happiness and well-being of others, enhancing our ability to engage positively in interpersonal relationships and see conflicts as opportunities to deepen our patience and humility.

- Intermediate: At this stage, we deepen our insight into the nature of reality, understanding interconnectedness and emptiness. Unlike the Beginner stage, where the focus is on cultivating basic empathy, the Intermediate stage involves integrating these insights into a more profound understanding of phenomena. Our meditation practices expand to include more nuanced techniques that emphasise direct insights into emptiness and the transformation of adversities into paths for personal and spiritual liberation. This leads to a transformation in how we perceive challenges and obstacles on the path — not just as learning opportunities, but as direct means to practice wisdom and dissolve the ego.

- Advanced: Here, we experience a seamless integration of our understanding and practice, with a deep realisation of emptiness and nonduality. Our emotional responses are characterised by equanimity and joyous compassion that are now stable regardless of external conditions. Our actions are spontaneous and perfectly aligned with the needs of the situation, embodying the bodhisattva ideal. We use every interaction as an opportunity to benefit others, demonstrating how to live in complete harmony with the teachings, with no separation between practice and daily life.

Across these stages, our view transforms from seeing challenges as personal adversities to seeing them as opportunities for enlightenment, reflecting the profound transformation of the Mahayana path. And this shift underscores the essence of the Mahayana path, where obstacles are not merely to be overcome, but are seen as integral to the cultivation of wisdom and compassion, the core qualities of the Bodhisattva.

(2) The armour of serving beings to suit their needs

So let’s turn to the second way in which we can wear the armour of dedication. How should we cultivate relationships on the Mahayana path? How can we be a good kalyanamitra or spiritual friend? Now, this is another very rich topic, which goes to the heart of the meaning of Sangha in Buddhism. We can’t cover this in depth right now, but to dip a toe in the water, I’d like to talk about giving people both what they want and what they need, building on Rinpoche’s example of the YouTube Bodhisattva from Week 4

This distinction touches on a complex aspect of human nature and also the path to enlightenment. Our wants are often immediate, superficial desires driven by attachment, ignorance, or craving, reflecting our conditioned responses to the world. Whereas our needs, particularly in a spiritual context, refer to what would genuinely benefit us in the long term, leading to true happiness, liberation from suffering, and ultimately enlightenment. Addressing this distinction involves navigating several trade-offs and conflicts:

- Immediate gratification vs. long-term benefit: We often want things that offer immediate gratification or relief from discomfort, but these desires may not align with what is beneficial for us in the long run. For example, we might want to spend our days in leisure and avoid difficult tasks, but what we need might be to engage in practices that challenge us and lead to our growth.

- Material comfort vs. spiritual development: A common want is for material comfort and security, which, while not inherently negative, can become a distraction from spiritual practice if pursued excessively. The need, from a Buddhist viewpoint, might be to cultivate detachment and contentment, focusing on spiritual development rather than accumulating material wealth.

- Affirmation of ego vs. realisation of non-self: We often seek affirmation of our ego, through recognition, success, or popularity. However, what we need, according to Buddhism, is to understand the concept of non-self (anatta) and to realise that attachment to ego is a source of suffering.

- Following comfortable beliefs vs. challenging illusions: We might want to cling to certain beliefs or views that make us feel comfortable or secure, but what we need is to challenge our illusions and understand the true nature of reality as is taught in Dharma.

So, much like the YouTube Bodhisattva, we will encounter these tensions both in our own practice and when we are aspiring to benefit others. So, when might something that we want not be what we need?

- When it perpetuates attachment and ignorance: If a want reinforces our attachment to the sensory world or deepens our ignorance of the true nature of reality, it’s likely not what is genuinely needed for our spiritual advancement.

- When it leads away from compassion: Desires that make us more self-centred or indifferent to the suffering of others are contrary to the development of compassion, which is a key aspect of what we need on the path to enlightenment.

- When it distracts from mindfulness and presence: Wants that lead us towards mindless consumption or distraction (such as excessive entertainment) can pull us away from mindfulness and presence, which are essential for understanding the Dharma.

- When it conflicts with ethical conduct: Desires that lead to actions conflicting with ethical conduct (shila) are not in line with what we need for spiritual progress.

Addressing these trade-offs requires prajña or wisdom to see beyond our immediate desires to the deeper needs that lead to lasting happiness and liberation. As practitioners or as bodhisattvas seeking to guide and benefit others, we need to skilfully navigate these waters, sometimes meeting people where they are to gradually guide them towards realising and embracing what they truly need. This also involves compassion and patient teaching, modelling behaviours and sometimes making hard choices that may not be immediately understood or appreciated by those we aim to help. And it can be even more challenging to make wise trade-offs that will benefit others if our own renunciation is not yet heartfelt and genuine.

6. Aspiration to accompany other bodhisattvas (verse 23)

The sixth aspiration, verse 23, is the aspiration to accompany other bodhisattvas:

[23] May I always meet and be accompanied by

Those whose actions accord with mine;

And in body, speech and mind as well,

May our actions and aspirations always be one!

This verse is basically saying, may I encounter others who act and think in the same way that I’m aspiring to do. As Rinpoche said, this is very important, especially for beginner bodhisattvas, to have this kind of support and companionship, others who are also on the path with us. This can really help us in actualising bodhichitta, and also in practising good conduct. This verse is about how we should behave towards people who we see as peers, those who are equals on the path. With people who are our equals, we should not be competitive, but instead speak kindly of them, and rejoice with them.

7. Aspiration to have virtuous teachers and to please them (verse 24)

The seventh aspiration, verse 24, is the aspiration to have virtuous teachers and to please them:

[24] May I always meet spiritual friends

Who long to be of true help to me,

And who teach me the Good Actions;

Never will I disappoint them!

Here Rinpoche said the aspiration is to encounter a virtuous Mahayana teacher and not to displease or disappoint them. So this doesn’t just apply to a Vajrayana guru or tantric teacher, as is revered in the Tibetan tradition, but also the virtuous spiritual teacher in the Mahayana path. He also said the word “master” perhaps isn’t the right word in Buddhism. He said “It’s a very human language, maybe a good word for something like Kung Fu”. But in Buddhism, a more appropriate word is the Sanskrit word kalyanamitra, which means a spiritual friend or a virtuous friend or even a fortunate or lucky friend. Our so-called guru or master should always be a virtuous friend.

Here we’re aspiring to encounter this virtuous friend at all times, in all kinds of occasions. For instance, at the moment we might feel like misbehaving, may he or she sort of turn up from a corner. Of course, it’s kind of annoying, but that’s our virtuous friend’s job — to save us from getting into trouble. So may we never dishearten them. As Rinpoche said, this last line is so beautiful. It means something like, “May I never break their heart”. And let’s never forget that meeting a teacher is already a sign of merit, of our past aspiration bearing fruit. So it would be appropriate for us to adopt an appreciative mindset — to rejoice, praise, make offerings and show courtesy and respect. As we saw before, part of what makes our human birth precious is that we have someone who is teaching us the Dharma. And we should always assume there are qualities in others that we do not yet know about or understand that are far better than we might have achieved ourselves. So we should always act with modesty.

This aspiration to meet spiritual friends always and at all times is like a first step on the journey to pure perception. In other words, seeing the Buddha everywhere. When we aspire, “May I always meet spiritual friends”, we’re aspiring may all circumstances become a Dharma teaching. For someone who really understands the view of emptiness, they can see anything as a Dhamma teaching. Anything can inspire them to see the truth. And I don’t mean in the ordinary sense of being inspired by a beautiful tree or a vast landscape or a beautiful sunset, or even amazing art or music. Yes, those things may touch us emotionally, but that doesn’t mean they inspire us to have greater insight into non-duality. It doesn’t mean they inspire us to see the Dharma, to see the truth. Whereas as Rinpoche said, if you have enough merit and wisdom, even just the sight of a falling leaf can bring about the awareness of impermanence and lead to spontaneous renunciation.

In the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, there’s a famous story of how the great master Patrul Rinpoche introduced the nature of mind to Nyoshul Lungtok, when they were both lying on the ground and looking at the night sky, outside Dzogchen monastery in Tibet. He said the very famous lines, “Do you see the stars up in the sky?” And in that moment, Nyoshul Lungtok got it — he was introduced to the nature of mind. And yet, as Rinpoche said, how many times have young lovers said those same words to each other, “Do you see the stars, my love?” But in a situation like that, those same words only become a source of greater attachment and delusion.

So this is what it means to have the merit to be able to see all circumstances as a teaching. It’s the difference between Nyoshul Lungtok being able to understand “Do you see the stars?” and accomplish insight into emptiness, and the young couple hearing the same words for whom seeing the stars just ends up as a source of greater attachment and delusion. So the key is learning to see all circumstances in a way that truly benefits us. And of course this is also practical, worldly advice. Can we bring a mindset of openness and learning when we face challenges and difficulties, rather than being closed, defensive, and emotionally reactive?

8. Aspiration to see the Buddhas and serve them in person (verse 25)

The eighth aspiration, verse 25, is the aspiration to see the Buddhas and serve them in person:

[25] May I always behold the buddhas, here before my eyes,

And around them all their bodhisattva sons and daughters.

Without ever tiring, throughout all the aeons to come,

May the offerings I make them be endless and vast!

In commenting on this verse, Rinpoche said, “I don’t know how to articulate this”. What we’re talking about here is seeing millions of Buddhas each surrounded by millions of Bodhisattvas right now as we open our eyes, not in the future. As he said, you just need to learn to see them. Not just to look, but to actually see them. And not only see them, but interact with them. Make offerings, ask questions, receive answers. And this is something we can do right now.

Rinpoche also said that Vajrayana people love this, because the Vajrayana always says if you want to see the Buddha, you really have to have the Guru’s blessing. And likewise, here this verse is saying, if you really want to see these ocean-like Buddhas, you don’t want to break the heart of your virtuous friend. So with these last few verses, we see how to relate to others:

- Verse 22: for those we see as lesser than us, we take care not to disrespect them.

- Verse 23: for those we see as our peers, we don’t compete with them and we rejoice with them.

- Verse 24: for those we see as our teachers, we take care not to disappoint them.

- Verse 25: for the Buddhas, we wish to always see them and never tire of making offerings to them.

Seeing Buddhas everywhere all at once

As Rinpoche said, let’s not forget this is part of the Avatamsaka Sutra, the Flower Ornament Sutra. He said, “I don’t know the definition of ornament in English, but it’s something like arranging things so that suddenly everything is accentuated and becomes kind of special”. When teaching this in Vancouver in 2024, he held up a flower and he said, “For instance, take this flower. In our limited human mind, we might say it’s an ornament. And subconsciously, or maybe consciously, the fact that this flower is here could make everything, all the other parts of this room beautiful, more bearable”. He continued, “The idea of the Avatamsaka Sutra is you just need to learn how to add that jewel to your life. For example, if you’re putting on jewellery like an earring, you might add a blue sapphire or a pearl and then everything works out. Now the ear is also nice. Next to the ear, the nose suddenly looks good. Next to the nose, the mouth suddenly looks good. And then everything looks good”. So this is non-ordinary seeing.

Rinpoche has talked a lot about the importance of non-ordinary seeing, or seeing beyond our ordinary habitual ways of seeing, even in the most basic teachings of Vipassana. He explains that the Sanskrit word “vi-“ means “special” or “extra” or “greater”. So vipassana actually means seeing the real deal or the true colour of phenomena. And here in the Avatamsaka Sutra, we have the the idea of sacred or pure perception, where we see everything as already enlightened, filled with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, which we further extend with the idea of pure perception in the Vajrayana.

And there’s also the element of deliberately making things beautiful and ornamenting them, for example, in our practices of offering and praise, such as mandala offering or arranging our shrine. This goes back to the idea of twofold aspiration and view that we talked about last week — it’s already pure and also may I make it pure. Similarly, here we have the twofold aspiration and view that it’s already beautiful, but may I make it beautiful. We’ll continue to explore this idea of pure perception in the coming weeks.

9. Aspiration to keep the Dharma thriving (verse 26)

The ninth aspiration, verse 26, is the aspiration to keep the Dharma thriving:

[26] May I maintain the sacred teachings of the buddhas,

And cause enlightened action to appear;

May I train to perfection in Good Actions,

And practise these in every age to come!

Here we’re aspiring to be able to hold the Dharma or the speech of the Buddhas, not just for a short duration, but for countless aeons. And we’re also aspiring that may I be able to fully illuminate, express, and teach the Dharma to others, so that the conduct of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra, noble in every aspect, arises in the mind stream of myself and others. In other words, I’m aspiring to manifest as a teacher. So the progression in previous verses went from seeing others as lesser, to seeing others as peers, to seeing others as teachers, to seeing the Buddhas everywhere. And now in this verse, my inner teacher, my Buddhanature is beginning to manifest.

10. Aspiration to acquire inexhaustible treasure (verse 27)

And even more so then in the last of this week’s verses, verse 27, which is the tenth aspiration, to acquire inexhaustible treasure:

[27] As I wander through all states of samsaric existence,

May I gather inexhaustible merit and wisdom,

And so become an inexhaustible treasury of noble qualities—

Of skill and discernment, samadhi and liberation!

We’re now aspiring to have an inexhaustible treasury of merit and wisdom. So even when we are going through hardships in benefiting others, we always have this inexhaustible treasury to draw upon. And we’re also encouraging ourselves by beginning to acknowledge we already possess the innate Buddhanature and innate Buddha qualities, so that when we encounter difficulties or people who belittle us, we can give ourselves more credit and rely upon our own goodness. Now as this verse says, we’re still wandering in samsara, so we’re not yet on the Third Path (or the First Bhumi). But nevertheless, we have acquired inexhaustible merit and wisdom. So we are on the Second Path, the highest stage before the Third Path (the Path of Seeing). And as with all of the verses, we continue to emphasise gathering merit and wisdom, because these are the causes of our further progress on the path.

We’re also becoming increasingly self-sufficient here on our path and in our practice, less reliant on outer circumstances, more able to fully embody the Buddha’s teaching that “You are your own master”. So, building on the previous verse where we were aspiring to be a holder of the Dharma, we are now aspiring to really manifest more of our innate Buddha qualities, this inexhaustible treasury of noble qualities, on this final stage as ordinary samsaric beings before we attain the Path of Seeing.

How can we be sincere in our aspirations?

I wanted to touch on one question from the 2016 teachings that Rinpoche gave on the Pranidhana-Raja in Taiwan, where someone asked, “How can we be sincere in our aspirations?” They said, “I feel when I say aspiration prayers, it’s never really sincere. And even if I think or feel I am sincere, I still think in reality that it’s not sincere. So please can you give us your thoughts about sincerity?”

And in his answer, Rinpoche said, “This is quite an important question. The issue of sincerity, whether or not we’re sincere, comes from whether or not we have the full picture, so to speak. And this is difficult.” He said, “First, I’ll tell you something practical, because even myself, many times I don’t feel sincere. But I aspire that if I keep on repeating my aspiration, if I keep on faking it, then maybe sometimes once in a blue moon it will be sincere. And then hopefully this sincere state will slowly take over.” Now, of course, this is true of all practice. If it was already perfect, it wouldn’t be practice. We’ve already talked about the benefits of taking refuge and making the aspiration of bodhichitta over and over again, ideally a hundred thousand times in our ngöndro practice, for example.

Rinpoche continued, “The real issue with sincerity is that we see things in the context of past, present and future. We always separate these three. The past is gone, it’s never going to come back. The future is a wild guess. Well, you can have an educated guess, but we’re never really certain. And the present, well, most of the time even the present is controlled by causes and conditions. So this separation or alienation of the three times is the real cause of our insincerity.”

He talked about how in the sutras there is an expression about having a gooseberry on your palm. So this refers to the Indian gooseberry or the myrobalan, which in Tibetan is called the kyurura. And supposedly when the arhats and sublime beings look at the world, that’s how they see it — as if looking at and through the gooseberry on their palms. The kyurura is mentioned in verse 224, one of the closing lines in the famous Chapter Six on wisdom in Chandrakirti’s Madhyamakavatara or “Entering the Middle Way”. And here it says that the Sixth Bhumi Bodhisattva’s wisdom is said to be “As clear as a myrobalan fruit held in his own hand”. And this is because the kyurura fruit is supposedly transparent and so the lines of one’s hand are visible through the fruit.

This is actually a wonderful analogy for self-transcendence or realisation of anatta, or we could say for being “in the world, but not of the world”. Because you can see the fruit, but you can also see through the fruit. It’s a bit like looking at a window: you can see the glass of the window, but you can also see through the window and see the view beyond at the same time. So the relative truth — the self, the window glass, the gooseberry — doesn’t go away. But the foreground and background shift, and now you can also see the ultimate truth — the emptiness or view through the window or the palm of the hand behind the gooseberry. And as our practice deepens, gradually we go beyond focusing on either just the foreground or just the background and we learn to see both relative and ultimate truths simultaneously as we progress towards non-duality.

Rinpoche said that likewise, for arhats and sublime beings, there is far less separation of past, present and future. For them, past is now, future is now, and now is now. And therefore there’s much less guessing. And he said of course we really have to reach that sort of level to really generate sincerity. For us, we’re still bound by time and space, so there’s a lot of guessing. And whenever there’s guessing, it’s understandable that sincerity is difficult. So we really need to hear more and contemplate more upon the grand Mahayana view of emptiness and nonduality, because most of the reasons that we’re not sincere are because our view is very limited. We don’t yet have the bird’s eye view, the grand Mahayana view of emptiness, which we’ll come to next week in Week 6.

Beginner’s mind

I’d like to close this week by bringing us back to basics and talking a little bit about the concept of beginner’s mind, or shoshin in Japanese. This comes from the tradition of Chan or Zen Buddhism, but it’s also valuable across the broader spectrum of Buddhist practice, including for us on the Bodhisattva path. Beginner’s mind is an attitude of openness, eagerness and lack of preconceptions when we approach the world, when we approach other people, and even as we approach our practice, even at the most advanced level. This mindset is particularly valuable for maintaining freshness and encouraging perseverance on the Bodhisattva path, for several reasons:

- Openness to learning: The Bodhisattva path is infinite. There are countless beings to help and endless lessons to be learned. Having a beginner’s mind keeps us open to new teachings and perspectives, which is essential for the continuous growth required on this path. We take the view that anyone or anything can be a source of learning and new insight.

- Flexibility in approach: With a beginner’s mind, we remain flexible and adaptable, able to respond to the needs of others in the most effective way possible. We don’t get stuck in our personal preferences or habits. This flexibility is crucial for a Bodhisattva, who seeks to benefit all beings in whatever ways are most skilful.

- Prevention of spiritual pride: The Bodhisattva path can be long and challenging. Achieving milestones of progress might lead to spiritual pride, whereas a beginner’s mind helps us to stay humble, reminding us that there is always more to learn and further to grow, thus helping us to keep our ego in check.

- Revitalisation of practice: A beginner’s mind imbues our practice with a sense of wonder and curiosity, preventing it from becoming routine or mechanical performance, including our practice of aspiration itself. So it keeps our practice fresh and meaningful, even after many repetitions or long periods of training. There is a famous Zen Buddhist saying: “Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water”. And in the same way, with a beginner’s mind, we learn how to make all of our practice and all of our activities fresh and vital.

- Compassion through relatability: With a beginner’s mind, we remember what it was like to be a beginner ourselves. And so it enables us to better help and relate to those just starting out on their path, fostering empathy and allowing us to be better as spiritual friends and companions.

So how might we do this?

- Mindfulness practice: Engaging in mindfulness meditation at whatever our level of practice helps us to cultivate awareness of the present moment, which helps us to cultivate an attitude of openness and curiosity about our moment-to-moment experience, essential for maintaining a beginner’s mind.

- Embrace learning as a continuous process: We can actively remind ourselves that learning should never stop. We can approach teachings and experiences with the idea that there is always something new or different to understand, even in what seems familiar.

- Challenge preconceptions: We can challenge our own ideas and beliefs about the practice and the path. Maybe we might study new texts, have Dharma discussions with our friends and companions on the path, or just questioning our own interpretation and understanding.

- Cultivate curiosity: We can make a conscious effort to cultivate curiosity in our daily life and practice. We can cultivate a practice of asking questions and exploring different perspectives, including the perspectives of other people that might be very different from us. And we can seek out new experiences, both in our lives and in the framework of our practice.

- Practice humility: We can recognise and accept our limitations and the vastness of what we don’t know. This humility is a cornerstone of the beginner’s mind. It keeps us open to learning and growth.

- Reflect on the fundamentals: And finally, we can always come back to the basics and reflect on the fundamentals. We can regularly return to the fundamental teachings and practices of Buddhism, approaching them as if for the first time. We can seek to rediscover their depth and nuance, which might otherwise be overlooked with familiarity. And we might find that indeed, we can never step in the same river twice, and that seemingly basic or familiar teachings can reveal themselves to us in a completely new way.

So in summary, by valuing and cultivating a beginner’s mind, we can cultivate the humility, openness and flexibility necessary to grow in our practice and effectively work for the benefit of all beings. This mindset is a powerful antidote to complacency, spiritual pride, and the stagnation of our practice, ensuring that our path remains living, vibrant and an inspiring journey.

So with that, let’s take a moment to dedicate our merit.

[Pause]

Thank you, and I look forward to seeing you again next week.

[END OF TEACHING]

Note: to read footnotes please click on superscript numbers

Transcribed and edited by Alex Li Trisoglio