Alex Li Trisoglio

Madhyamakavatara Week 6: Emptiness of Emptiness

Week 6: Emptiness of Emptiness

12 July 2017 / 86 minutes

Question: How is emptiness understood in the Mahayana? What is the emptiness of emptiness? How can we practice nonduality?

Reference: Madhyamakavatara verses 6:179 – 6:226

Transcript / Pre-reading / Audio / Video

Introduction: Review of Week 5 and summary of Week 6 [Audio/Video timing: t = 0:00:02]

Good evening everybody. I’m Alex Trisoglio, and I’d like to welcome you to Week 6 of “Introduction to the Middle Way”. As usual, let’s start with a brief review of what we did last week.

• The idea of self is baseless: As you may recall, last week was all about establishing that the self of the person does not truly exist, and we did this by examining the idea of the ‘self’, which is what we cling to, and showing that it is baseless. And we saw that because the idea of the self is baseless, not only does it mean there is no ‘truly existing self of the person’, but it means we can choose a different idea of the self. We can reinvent ourselves: as a Buddhist, as a bodhisattva on the path, as a deity if we’re doing sadhana practice; and this is not easy, but it’s doable.

• Conventional truth collapses upon analysis: The second thing we talked about was: conventional truth collapses upon analysis. As we said, if we analyze the conventional truth, all elaborations cease. All thought, all language collapses. And so, partly as a result of that, Chandrakirti does not seek to analyze the conventional. He just follows the consensus of everyday people.

• Horse practice and donkey practice: Another thing we came across is Padampa Sangye’s teaching about the horse practice and the donkey practice. And here, Rinpoche said, you start with a very emotional, devotional kind of practice, praying to the Buddha, thinking he’s in front of you, visualizing him clearly, with a subject and an object, tears in your eyes – all of that. And then, suddenly, you remember that Buddha is emptiness. Buddha is not separate from your mind. There is no truly existing Buddha. And then, you don’t know what to do – because your devotion disappears, the tears stop, the yearning and the longing stops – and Padampa Sangye said when that happens, it’s like riding a horse. But almost at once we think, “I want to get back to my old model of practice that’s filled with emotion and devotion”. And then, of course, we seek to bring back the Buddha, all the emotion and crying and the rest, and Padampa Sangye says that is like dismounting the horse and riding the donkey.

That’s going to be important to us this week, because we’re going to focus on the ’emptiness of emptiness’. Nonduality. And we’re also going to start asking, “what does that mean, for our practice?”. We’ll start by completing Chapter 6, verses 179-226, concluding with a lovely verse about how the king of swans will spread his broad wings that are the two truths – wisdom and skillful means – to lead the other swans to liberation. So that’s where we’re going to end up.

Then we’ll turn to the Heart Sutra, where I’ll go through some of the teachings Rinpoche gave on “Prajñaparamita” in Kathmandu earlier this year, in April-May. And along the way we’ll pause for a little practice, because, as we’ve been saying many times, we can’t understand nonduality except through our meditation. So this week, I am not going to try to rely on words alone!

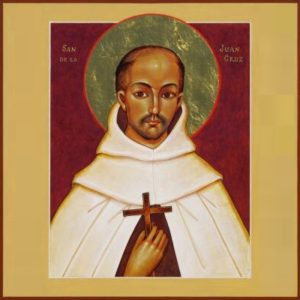

Both Bull and Self Transcended [t = 0:04:10]

We now come to the 8th of the 10 Bulls:

8. Both Bull and Self TranscendedWhip, rope, person, and bull – all merge in No-Thing.

This heaven is so vast no message can stain it.

How may a snowflake exist in a raging fire?

Here are the footprints of the patriarchs.

Comment: Mediocrity is gone. Mind is clear of limitation. I seek no state of enlightenment. Neither do I remain where no enlightenment exists. Since I linger in neither condition, eyes cannot see me. If hundreds of birds strew my path with flowers, such praise would be meaningless.

So that’s where we’re going to end up. And as you may know, the image that goes with that verse is simply the enso. It’s a very beautiful expression or encapsulation of nonduality

The struggle before attaining the goal [t = 0:05:13] [✚ Additional material not in audio recording]

But we know from the Hero’s Journey that before we can get to our goal, we have to go through a big struggle. Let’s briefly review our progress so far in terms of the Hero’s Journey, and get a sense of the struggle that confronts us as we enter Week 6 (here I’m using Joseph Campbell’s names for the 3 acts: departure-initiation-return):

Act I: Departure (the ordinary world – “mountain is mountain”)

• Act I, Scene 1 (“The Setup”): In Week 1, we begin in the ordinary world, where we start to ask questions about our life. Perhaps we realize that all our hopes and plans, our work and relationships, aren’t bringing us the happiness and freedom that we anticipated. Maybe we feel there has to be more to life than this. Then there is some kind of catalyst. We hear about the possibility of enlightenment, we come across the Buddha’s teachings, and we learn that they are founded on a realization of emptiness and nonduality. We hear that there is something called the Middle Way. We hear the Theme of the story and it touches us emotionally. It resonates with us. We don’t really understand it, but we are intrigued. We want to learn more about the Middle Way.

Act II: Initiation (the unknown world – “mountain is not mountain”)

• Act II, Scene 1 (“The Road of Trials” and the B Story): In Week 3, the adventure begins. We start to meet the ‘bad guys’ that believe in truly existing phenomena: the Hindu Samkhya that believe in truly-existing self-arising, and the early Buddhist Vaibhashika and Sautrantika schools that believe in truly existing other-arising. The plotline also introduces the “B Story” (the “love story”). We started out on this journey in order to refute truly existing ideas of self, since we know that self-clinging is the reason we’re trapped in samsara. But now we see the B Story as well: we realize that if we want to function in the world, we can’t ignore the conventions of ordinary people. Both of the Two Truths are important. And as bodhisattvas, we want happiness and liberation for all sentient beings; we don’t want to get caught in nihilistic refutations. Now we also have the B Story of our love and compassion for sentient beings.

As Joseph Campbell puts it, the Hero only comes out of this Dark Night of the Soul when “he or she moves beyond the pairs of opposites to a state of divine knowledge, love, compassion and bliss.” This is apotheosis: the culmination or climax, the transcendence of ordinary duality. In our case, we realize that our path is not just deconstructing the truly existing self and showing that “form is emptiness”, but in establishing the nondual understanding of the emptiness of emptiness. We realize that wisdom comes together with compassion and skilful means. We understand the paradoxical truth of the Heart Sutra: “form is emptiness; emptiness also is form”, and emerge with the realization of Prajñaparamita. We have secured what Campbell calls the “ultimate boon” (that which has the greatest benefit). We have achieved the goal of our quest.

In Week 7, we will enter Act III “The Return”, where we shall attempt to return with the ultimate boon to the ordinary world. In our case, we will explore how we can bring the view of emptiness and nonduality into our practice, and then finally into our everyday life.

The struggle before attaining the goal [t = 0:05:22]

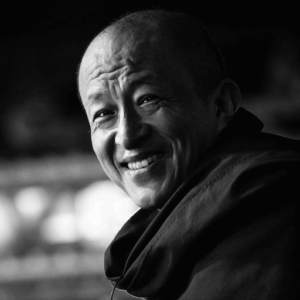

Many of you this week have been talking about and expressing this struggle. As you seek to engage in these Madhyamaka teachings, it can bring up a certain kind of nihilism. You might find yourself asking questions like, ‘If everything is emptiness, why bother?’ Why do anything at all? If everything in conventional truth is just like a magical illusion, then why does any of it matter? If there is no truly existing suffering, why should I seek to help suffering beings? And if there’s no enlightenment, why should I practice? It’s very easy to fall prey to these doubts. And this has been a big challenge in Western philosophy as well, for the existentialists, and in particular (although he didn’t call himself an existentialist) for Albert Camus. Camus was struck by the story of Sisyphus, a figure in Greek mythology who was condemned to repeat forever the same meaningless task of pushing a boulder up a mountain only to see it roll down again. He saw this same meaninglessness and absurdity in our everyday lives. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains how he expresses his philosophy in the book, ➜The Myth of Sisyphus:

“There is only one really serious philosophical problem,” Camus says, “and that is suicide. Deciding whether or not life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question in philosophy. All other questions follow from that” (The Myth of Sisyphus, 3).

Camus sees this question of suicide as a natural response to an underlying premise, namely that life is absurd in a variety of ways. … it is absurd to continually seek meaning in life when there is none, and it is absurd to hope for some form of continued existence after death given that the latter results in our extinction. But Camus also thinks it absurd to try to know, understand, or explain the world, for he sees the attempt to gain rational knowledge as futile. Here Camus pits himself against science and philosophy, dismissing the claims of all forms of rational analysis: “That universal reason, practical or ethical, that determinism, those categories that explain everything are enough to make a decent man laugh” (The Myth of Sisyphus, 21).

From Chandrakirti’s perspective, you could perhaps say that Camus has completed the task of deconstruction. He has established that form is emptiness. He has shown there is no truly existing, eternalistic ‘meaning’. But now he is truly lost.

The confrontation with Mara [t = 0:08:14]

And far from being unusual, this kind of fight with our demons is an essential part of the Hero’s Journey, as we have seen. It corresponds to our fight with those last remnants of our old ‘self’ – this baseless story of ‘self’ that we used to tell ourselves, and that doesn’t want to be rewritten. Our demons are our habits.

There are several versions that describe the stages of the Hero’s Journey. Joseph Campbell’s ➜original version (from his 1949 book The Hero With a Thousand Faces) has 17 stages, and the stages corresponding to where we find ourselves in Week 6 include:

[from Act II: Initiation]

9. Atonement with the Father: In this step the Hero must confront and be initiated by whatever holds the ultimate power in his or her life. In many myths and stories this is the father, or a father figure who has life and death power. This is the centre point of the journey. All the previous steps have been moving into this place, all that follow will move out from it. Although this step is most frequently symbolized by an encounter with a male entity, it does not have to be a male; just someone or thing with incredible power.

10. Apotheosis: When someone dies a physical death, or dies to the self to live in spirit, he or she moves beyond the pairs of opposites to a state of divine knowledge, love, compassion and bliss.

11. The Ultimate Boon: The ultimate boon is the achievement of the goal of the quest. It is what the person went on the journey to get. All the previous steps serve to prepare and purify the person for this step, since in many myths the boon is something transcendent like the elixir of life itself, or a plant that supplies immortality, or the holy grail.

Campbell’s version fits the Madhyamaka story well. In our case, the ‘father figure’ with life or death power is the ego. The apotheosis in which we “die to the self, to live in spirit” and “move beyond the pairs of opposites” describes nonduality very well. And the ultimate boon, the goal of our question, is enlightenment.

Blake Synder wrote a ➜15-stage version of the story structure in his book Save The Cat, which is specifically for movie screenplays. It’s quite similar to the Hero’s Journey, and includes very specific turning points in each act. The stages from his structure that correspond to Week 6 are:

[from Act II]

10. Bad Guys Close In: Doubt, jealousy, fear, foes both physical and emotional regroup to defeat the Hero’s goal, and the Hero’s “great” situation disintegrates.

11. All is Lost: This is the opposite moment from the “great” situation of the Midpoint: the moment that the Hero realizes they’ve lost everything they gained, or everything they now have has no meaning. The initial goal now looks even more impossible than before.

12. Dark Night of the Soul: The Hero hits bottom, and wallows in hopelessness.

13. Break Into Three (Choosing Act III): Thanks to a fresh idea, new inspiration, or last-minute Thematic advice from the B Story (usually the love interest), the main character chooses to try again.

This fits our emotional journey along the Madhyamaka very well. As we noted previously, we have spent many weeks refuting all these different views, and come to a place of emptiness where there are no views. But now it seems we are left with no stories or purpose at all, and so we enter the Dark Night of the Soul. We hit bottom. We have to confront our demons.

As Joseph Campbell noted, this is very similar to the Buddha’s own life story. In the Buddha’s case, he has to confront Mara and his daughters before enlightenment. Mara is a demon – the Lord of Death – and his name means ‘destruction’. He represents our ego, our emotions, our ignorance. So Siddhartha is sitting beneath the bodhi tree, about to attain his enlightenment, and Mara brings his most beautiful daughters to seduce him: Tanha (craving), Arati (aversion and discontentment) and Raga (attachment and desire). But Siddhartha remains unmoved in his meditation. So then Mara brings vast armies of monsters to attack him, and yet still, Siddhartha sits peacefully, unmoving. Then Mara claims that the seat of enlightenment rightfully belongs to him, and not to the mortal Siddhartha. And all of Mara’s demon soldiers cry out, “I am his witness!”. Mara turns to Siddhartha and says, “who will speak for you?”. And in a very famous moment, Siddhartha reaches his right hand to touch the earth, and the earth itself speaks: “I bear you witness”. Mara disappears. And as the morning star rises in the sky, Siddhartha realizes enlightenment and becomes a Buddha.

So maybe we can see our own hopelessness, our own depression and nihilism as a manifestation of Mara. The Madhyamakavatara is a ‘View’ teaching, so Chandrakirti doesn’t give us much practice advice. We’ll have to talk about that separately. But one thing we will see today in the commentary is the importance of compassion. Whatever may be happening with our emotions, even if we’re feeling a sense of hopelessness, we must never give up our compassion. We’ll also understand a little more about why Chandrakirti praised compassion in his homage at the beginning of the Madhyamakavatara, and why it is so important for us in this chapter.

We’ll also return to the importance of practice. As Rinpoche often says, if we’re feeling a loss of inspiration or a sense of hopelessness, that’s another reason why it’s so important to generate merit. In verse 6:4 at the beginning of this chapter, Chandrakirti explained to whom should the Madhyamika be taught. And we learned that if we’re the kind of students who have tears in our eyes and the hairs on our body quiver when we hear these teachings on emptiness, then yes, we should be given the full teachings on the emptiness of the person and the emptiness of phenomena. But if it isn’t yet our natural inclination to respond that way, then we need to accumulate more merit. And as we’ve been saying throughout these teachings, that can only be done through practice. Practice really is 98% of the Madhyamaka path.

Verse 6:179

How the Buddha taught two kinds of selflessness [t = 0:14:21] [MAV PDF page 296]

The structural outline for the verse that we’ll cover today is very simple, in just two parts:

• 6:179-6:223: first we’ll explain emptiness as it is to be realized by the Mahayana, and that corresponds to the logic tree #12 in the structural outline (page 442).

• 6:224-6:226: the last three verses of Chapter 6 are a summary of the qualities attained. Remember, we’re accomplishing the paramita of wisdom here, so that’s what we attain at the end of the sixth bhumi, once we have completed and perfected that prajña-paramita.

Turning to the text, verse 179 begins by reminding us that Buddha taught emptiness in two ways: through the ‘selflessness of the person’, and the ‘selflessness of phenomena’. It’s actually a very straightforward verse. Most of the verses today are pretty straightforward, simply a list of the different kinds of emptiness that are realized in the Mahayana.

[6:179] In order to liberate sentient beings,

The two divisions of individual and phenomenal selflessness were taught.

Accordingly, the teacher repeatedly taught this point

In various ways for various trainees.

Rinpoche didn’t give much commentary when he taught these verses, so I’ll be dipping a little into Mipham’s commentary today (from the Padmakara translation of the Madhyamakavatara). And even in Mipham Rinpoche’s commentary on verses 179-226, there are only really two significant sections, but they’re both quite important.

The first is a commentary on this verse, and Mipham asks: do the shravakas realize the non-self of phenomena? We discussed this question in Week 2 when we talked about the baby prince and the ministers (Chapter 1, verse 8). And as we said then, to attain samsara we have to remove our emotional defilements, which means we need to realize the selflessness of the person. Otherwise, you can’t get rid of the notion of an innate “I”, which is what we cling to. And since ultimately the selflessness of the person and the selflessness of phenomena are no different, you can also say that the shravakas and pratyekabuddhas must realize the selflessness of phenomena. As Mipham says, “it is rather as if when somebody drinks a mouthful of seawater, one cannot deny that he is drinking the sea”.

So the question is, if they realize the emptiness of the person, why don’t they also realize the emptiness of phenomena? There are three reasons. Firstly, their interest. The shravakas’ only interest is in getting out of samsara. They’re not necessarily aspiring to liberate all sentient beings. The other two reasons are about the presence of internal and external conditions. The internal condition is, have they cultivated enough compassion and aspiration? And the external condition is, have they met a teacher of the Mahayana?

Also, the nonexistence of the personal self is what Mipham calls a ‘non-affirming negative’: it is differing from the Mahayana view of the emptiness of everything, including the emptiness of emptiness. The emptiness of everything is beyond the 62 misconceptions or wrong views (Sanskrit: drishtigata, दृष्टिगत. The ➜62 wrong views can be found in the ➜Brahmajala Sutta), one of which is clinging to this ‘non-affirming negative’ or mégak (Wylie: med dgag, Tibetan: མེད་དགག་). Now of course the Prasangika also talk about the nonexistence of the personal self, but they don’t cling to it, so this fault does not apply to them. But if one is on the Shravakayana path, there is a real danger that one could become attached to nirvana as a consequence of this clinging.

According to their own path, shravakas and pratyekabuddhas won’t realize their fruit unless they fully understand the emptiness of the person. And since, as we discussed earlier, a full understanding of the emptiness of the person necessitates an understanding of the phenomenal aspects of the person, i.e. the aggregates, we conclude that the Madhyamaka must be common to all three vehicles. Mipham concludes that there really is only one final vehicle, which we’ve already seen in verse 6:79:

[6:79] Apart from this very path of the venerable Acharya Nagarjuna,

Other paths will not serve as means to attain Peace,

As they incompletely [grasp] the all-concealing and absolute truths;

They fail to establish liberation.

In order to attain buddhahood, we need to completely realize both ultimate and conventional truths. In other words, we need to realize the nondual view, or what the Pundarika Sutra (Lotus Sutra) terms “the state of equality of all phenomena.” And yet we also know that even though followers of different paths may all study Madhyamaka, some become bodhisattvas or buddhas, while others become shravakas or pratyekabuddhas. This means that merely studying and practicing the Prajñaparamita cannot be the cause of Buddhahood. So what’s the difference? We have seen previously that the fourth of the Four Seals that set out the Mahayana Buddhist view of reality is that “nirvana is peace”. In the Shravakayana this “peace” refers to the peace of cessation, but Rinpoche explains that in the Mahayana it is understood to mean “beyond extremes”, which is another way of saying “the state of equality of all phenomena”.

So Prajñaparamita is the realization of the evenness – the equality – of samsara and nirvana, and it transcends the extremes of either existence (samsara) or peace (nirvana, or ‘cessation’). And if you don’t have this equality – if like the shravakas, you have a preference for nirvana – then that means you have a view, and when analyzed it is shown to be an extreme view that is based on a ‘truly existing’ belief. And remember that Chandrakirti has no views. He certainly doesn’t hold the view that nirvana is preferable to samsara. But if the shravakas can study the Prajñaparamita and end up with a different conclusion from the followers of the Madhyamaka, what accounts for the difference in their realization?

Based on this reasoning, Mipham concludes that since the Prajñaparamita teachings themselves cannot account for the difference, the true cause of Buddhahood – in other words what distinguishes the Shravakayana and Mahayana – is the far greater emphasis on compassion and accumulation of merit in the Mahayana. And this is why bodhicitta is stressed so heavily in the Mahayana. As Rinpoche says, you might be an incredible scholar and know every detail of the Madhyamaka teachings. But unless you have cultivated bodhicitta, all your learning is going to get you nowhere when it comes to progress on the bodhisattva path.

Mipham continues, saying that if you think you have supposedly realized nonduality, but you’re still drawn only to the extreme of nirvana, it means you don’t actually realize the equality of all things. In that case, even if you realized the luminosity of the uncontrived nature of mind, you could still fall into the extreme position of the shravakas. So that’s why the Mahayana emphasizes the dharmadhatu, the Great Equality which does not reject samsara, and nor does it abide in the peace of nirvana, because it’s fully endowed with enlightened activities.

And that’s also why our focus in Week 6 will be nonduality, the emptiness of emptiness, and the union of the two truths. It’s very good for us to contemplate on this, just as practice advice for ourselves. Has our practice become overly focused on some kind of inner accomplishment? Or are we actually practicing bodhicitta as well? Are we manifesting as bodhisattvas?

Verse 6:180

Showing what is to be realized through the Mahayana [t = 0:21:16] [MAV PDF page 296]

What is to be realized in Mahayana is these sixteen kinds of emptiness. There’s the long list here, which we’re going to go through in the following verses. And they’re later divided or regrouped into four in verses 219-222.

[6:180] When elaborate, of emptinesses

He taught sixteen, when brief

He taught four – all these

Are also taught to be the Mahayana.

Taken together, these sixteen and these four fully teach the selflessness or emptiness of phenomena. The sixteen types of emptiness are:

(1) Emptiness of inner (6:181-6:182)

(2) Emptiness of outer (6:183-6:184ab)

(3) Emptiness of both outer and inner (6:184cd)

(4) Emptiness of emptiness (6:185-6:186)

(5) Emptiness of vastness (6:187-6:188)

(6) Emptiness of the ultimate (6:189-6:190)

(7) Emptiness of compounded (6:191)

(8) Emptiness of uncompounded (6:192)

(9) Emptiness of limitless (i.e. what is beyond extremes) (6:193)

(10) Emptiness of what is without beginning or end (6:194-6:195)

(11) Emptiness of what should not be discarded (6:196-6:197)

(12) Emptiness of true nature (6:198-6:199)

(13) Emptiness of all phenomena (6:200-6:201ab)

(14) Emptiness of characteristics (2:201cd-6:215)

(15) Emptiness of the non-apprehended (unobservable) (6:216-6:217)

(16) Emptiness of nature without substantial existence (non-things) (6:218)

Condensed into four, we have:

(1) Emptiness of things

(2) Emptiness of non-things

(3) Emptiness of the nature itself

(4) Emptiness of the transcendent quality (other-nature)

These sixteen and four kinds of emptiness describe all those aspects of emptiness which the shravakas and pratyekabuddhas do not realize because they may not have the interest, the merit, or the teacher.

Verses 6:181-6:182

(1) Emptiness of inner [t = 0:21:56] [MAV PDF page 297]

[6:181] Because its nature is [non-inherent]

Eyes are empty of eyes

Likewise the ears, the nose, the tongue

Body and mind too are explained as such.

[6:182] Not continuously dwelling, and also not disintegrating –

The six senses, eyes and so forth,

Are without inherent existence.

This is regarded as emptiness of inner.

The ’emptiness of inner’ refers to the six senses and the six sense consciousnesses (in Buddhism, ‘mind’ is considered to be one of the senses alongside vision, touch, taste etc.). Verse 181 refers to the eye-sense and the other five senses; verse 182 is the eye-consciousness and the other five sense consciousnesses. I think it’s worth just taking a moment to remind ourselves of the relevant explanation in the Abhidharma.

According to the Abhidharma, the way that the senses work, to take the example of vision, is that the eye consciousness arises dependently, based on the internal sense organ (the eye); and the external sense object (the form):

(INTERNAL) SENSE ORGAN (e.g. eye) + (EXTERNAL) SENSE OBJECT (e.g. form) ➜ SENSE CONSCIOUSNESS (e.g. eye-consciousness)

And when they meet, this is ‘contact’, which is one of the Twelve Links of Dependent Origination, and that, in turn, generates ‘feelings’ and so on. So if we look at a subset of the ➜Twelve Links:

• (3) Vijñana (consciousness): this is consciousness, which is ‘raw awareness’ or subjectivity.

• (4) Nama-rupa (‘name and form’): this refers to the psychological and physical aspects of the person.

• (5) Salayatana (the six sense bases): this includes the sense organs and their objects.

• (6) Phassa (contact): this is the ‘contact’ we just talked about, which is the meeting of the subjective consciousness, the sense object, and the sense organ. And that leads to:

• (7) Vedana (‘feelings’ or ‘sensation’): pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral sensations, which lead to:

• (8) Tanha (craving): you get craving and clinging and then the rest of samsara is generated.

These verses refer back, then, to the classic teachings on the Twelve Links. And when we refer to the six senses, the six sense objects and the six sense consciousnesses, these are:

• Eye + Form ➜ Eye consciousness

• Ear + Sound ➜ Ear consciousness

• Nose + Smell ➜ Nose consciousness

• Tongue + Taste ➜ Tongue consciousness

• Skin + touch/tactile sensation ➜ Body consciousness

• Mind + intellectual sensation (i.e. thoughts or ideation) ➜ Mental consciousness

It’s also worth noting that the Madhyamaka is different from the Cittamatra, because as we’ve just described, in the Madhyamaka there are only six consciousnesses corresponding to the six senses, and ‘self-awareness wisdom’ is included in the sixth consciousness. Whereas for the Cittamatra and Zen, there are eight consciousnesses. We’ll come to these when we look at the Heart Sutra a little later:

• 7th consciousness = manas-vijñana, which appears in the Heart Sutra translation as the ‘dhatu of dharmas’. This refers to deluded awareness, which discriminates and judges. On one hand, it localizes experience through thinking; and on the other hand, it universalizes experience through intuitive perception of alaya-vijñana.

• 8th consciousness = alaya-vijñana, which is known as the ‘mind-consciousness dhatu’ or ‘storehouse consciousness’, and it is the base of the other seven. Indeed, as we saw during the Cittamatra explanation of mind (in verse 6:47), it is the base for all phenomena.

This verse is the only other one in verses 179-226 where Mipham offers a more extended commentary. Here he asks, what do we mean when we say (as verse 6:181 says) that eye is ’empty of eye’? This is actually quite important because the various Tibetan schools talk about emptiness in slightly different ways. Mipham quotes Chandrakirti, who says in his autocommentary (or self-commentary) on the Madhyamakavatara:

The expression ‘The eye is empty of eye’ (and so on for all other phenomena) expresses the nature of emptiness. Emptiness does not mean the absence of something from something else, as when one says that the eye is devoid of an inner agent or of the duality of the subject and object of perception.

Mipham contrasts this with people who say things like “the eye isn’t empty of eye, it’s empty of true existence”. Mipham says, “what could this mean?”. It could only refer to a truly existing eye or a truly existing non-eye, and nobody’s going to confuse a conventionally appearing eye with a truly existing non-eye. So if there’s another truly existing eye together with the conventionally-appearing not-truly-existing eye, and then we try to remove the not-truly existing eye, we’ll be still left with an eye. Our opponents may claim this is a ‘mere appearance’, but by definition, it must then be truly existing, which is a real problem. As Mipham says, when we burn a chariot, everything disappears, including its appearance. So if we remove the truly existing eye, we should also remove its appearance. Our opponents then object: “well, if the eye doesn’t truly exist, it couldn’t appear”; but we’ve already dealt with this objection in Week 4, in verses 6:107-6:113, right before we introduced dependent arising in verse 6:114. Mipham responds in a rather dismissive tone:

The eye’s emptiness of itself does not at all invalidate the eye’s appearance. Indeed the Madhyamika teaching asserts that phenomena, despite being empty, do nevertheless appear. The proponents of the other, utterly foolish, theory are passionately attached to words, but not to their meaning. Their idea is something at which the learned merely smile, rejecting it at first glance, as indeed they should.

Verses 6:183-6:184ab

(2) Emptiness of outer [t = 0:27:42] [MAV PDF page 297]

The next two verses are ’emptiness of outer’, which refers to form and the outer aggregates, or what just talked about previously as the ‘sense objects’

.[6:183] Because of its nature,

Form is empty of form.

Likewise sound, scent, taste and touch:

All phenomena are so.

[6:184ab] Form and so forth have no inherent nature,

This is outer emptiness.

This refers to the Five Skandhas, which are:

• Form (rupa): matter, body, material form.

• Sensation (vedana): sensory experience – pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral. Bear in mind this is not the same as ‘feelings’ in the sense of emotions. So it’s more accurate to use the word ‘sensation’, but if we use the word ‘feeling’ to describe the second aggregate, remember that it refers to sensations, not emotions.

• Perception (samjña): the sensory or mental process that registers, recognizes, and labels (so things like the shape of a tree, the colour green, the emotion of fear: all those are perceptions, labels, imputed phenomena).

• Mental formations (samskara): these are any mental imprints, or habits, or conditioning that’s triggered by an object; any process that makes a person initiate action. It’s similar to what we talked about last week when we discussed ‘operant conditioning’ and behaviourism. It’s very similar: the habitual patterns that can be triggered by a stimulus, by an object.

• Consciousness (vijñana): there are the six types corresponding to the six senses, as we’ve just seen. And if you follow the Cittamatra, then you have two more for a total of eight types.

So in the Heart Sutra the section that corresponds to these verses is:

In emptiness, there is no form, no feeling, no perception, no formation, no consciousness; no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no appearance, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no dharmas; no eye dhatu up to no mind dhatu, no dhatu of dharmas, no mind consciousness dhatu;

So that’s basically listing everything we have just talked about:

(1) “no form, no feeling, no perception, no formation, no consciousness” – these are the five aggregates;

(2) “no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind” – these are the six senses;

(3) “no appearance, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no dharmas” – these are the six sense objects;

(4) “no eye dhatu up to no mind dhatu, no dhatu of dharmas, no mind consciousness dhatu” – these are the six (or eight) consciousnesses.

So as you can see, these verses are very much connecting us to the Heart Sutra already.

Verse 6:184cd

(3) Emptiness of both outer and inner [t = 0:30:44] [MAV PDF page 298]

The last two lines of verse 184 introduce the ’emptiness of outer and inner’, the 3rd of the 16 emptinesses.

[6:184cd] The absence of inherent existence in both [outer and inner phenomena],

Is emptiness of outer and inner.

In the commentary Rinpoche says it refers to the 18 dhatus of another person, and Mipham has an alternative commentary. He says it refers to the five inner supports of the five sense organs, the kogpa (Wylie: khog pa, Tibetan: ཁོག་པ་). These are the material supports for the senses, which are not to be confused with the senses themselves, and according to the Abhidharma they are included within consciousness, but not included within the senses, so therefore they’re both outside and inside. According to the Abhidharma, they’re actual physical objects. They have different shapes and are located in the eyes, ears, tongue, and so forth. In Sanskrit they are called the pasada rupas. So for example, the eye sense is supposedly “very small, no bigger in size than the head of a louse”. The ear sense is “in the interior of the ear at a spot shaped like a finger ring and fringed by tender tawny hairs”. You can find these descriptions of the pasada rupas in the Abhidharma, as well as details of where they supposedly exist in the body.

Verses 6:185-6:186

(4) Emptiness of emptiness [t = 0:31:59] [MAV PDF page 298]

Verses 185-186 introduce the 4th emptiness: the emptiness of emptiness. This was taught to overcome the notion that emptiness truly exists, because some unskilful students might read the Madhyamaka and conclude “Aha! Chandrakirti has established the view of emptiness. That must be my view”. But actually it’s not like that at all.

[6:185] All phenomena’s lack of inherent existence,

Is explained as emptiness by the wise.

That emptiness also,

Is regarded as being empty of any essence.

[6:186] The emptiness of that known as emptiness,

Is known as emptiness of emptiness,

And was taught to avert the fixation

Of those holding emptiness as real.

Since we’ve heard this many times already, I thought it might be helpful to approach this with a couple of readings that use slightly different language, as they might give us a different way to access and understand the meaning of the “emptiness of emptiness”. I’d like to offer two quotes from Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, firstly from the section on the “Eightfold Path” in The Myth of Freedom (1976) (pages 93-94):

The first point the Buddha made has to do with “right view.” Wrong view is a matter of conceptualization. Someone is walking toward us – suddenly we freeze. Not only do we freeze ourselves, but we also freeze the space in which the person is walking toward us. We call him “friend” who is walking through this space or “enemy.” Thus the person is automatically walking through a frozen situation of fixed ideas – “this is that,” or “this is not that.” This is what Buddha called “wrong view.” It is a conceptualized view that is imperfect because we do not see the situation as it is. There is the possibility, on the other hand, of not freezing that space. The person could walk into a lubricated situation of myself and that person as we are. Such a lubricated situation can exist and can create open space.

Of course, openness could be appropriated as a philosophical concept as well, but the philosophy need not necessarily be fixed. The situation could be seen without the idea of lubrication as such, without any fixed idea. In other words, the philosophical attitude could be just to see the situation as it is. “That person walking toward me is not a friend, therefore he is not an enemy either. He is just a: person approaching me. I don’t have to pre-judge him at all.” That is what is called “right view.”

There’s another lovely quote, this time from Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism (1973), from the section on “Shuntaya” (page 195):

Nagarjuna’s conclusions are summed up in the principle of “non-dwelling,” the main principle of the Madhyamaka school. He said that any philosophical view could be refuted, that one must not dwell upon any answer or description of reality, whether extreme or moderate, including the notion of “one mind.” Even to say that non-dwelling is the answer is delusory, for one must not dwell upon non-dwelling. Nagarjuna’s way was one of non-philosophy, which was not simply another philosophy at all. He said, “The wise should not dwell in the middle either.”

I find this to be a very beautiful way of talking about the emptiness of emptiness. And we’ll come back to this again when we talk about the Heart Sutra.

Verses 6:187-6:188

(5) Emptiness of vastness [t = 0:35:45] [MAV PDF page 298]

These two verses are pretty straightforward. Mipham explains the ’emptiness of vastness’ was taught in order to counter the Vaibhashika belief in a permanent and truly existing space or infinite immensity.

[6:187] Pervading without exception

All sentient beings and the outer world,

Without limits, as in the [Four] Boundless,

The directions [of space] are vast.

[6:188] In the tenfold entirety of [of space],

The directions are empty.

This is the emptiness of vastness

Taught to avert fixation on vastness.

Verses 6:189-6:190

(6) Emptiness of the ultimate [t = 0:36:04] [MAV PDF page 299]

The 6th kind of emptiness is ’emptiness of the ultimate’. Mipham explains that this refers to Dharmakaya (in the Mahayana) or nirvana (in the Shravakayana). Actually, several commentaries on the 10 Bulls say that the 8th bull that we met earlier today also represents Dharmakaya. So why did Buddha teach this ’emptiness of the ultimate’? To dispel the wrong view of the shravakas that cessation or nirvana is a truly existing phenomenon. Again, we have to be careful, because as soon as our idea of the ultimate becomes a truly existing phenomenon and the ultimate goal of our practice and our path – whether it’s enlightenment or the three kayas or anything like that – we fall into the same trap. Rinpoche said many of us only go to Dharma centres and practice in the first place because we think nirvana truly exists. But then we end up clinging to the idea of nirvana. We have big expectations and then endless disappointment and guilt. I think that’s lovely practice advice: ask yourself if you’re starting to relate to your own practice that way. Have you started to develop some kind of clinging to nirvana or to enlightenment?

[6:189] Being the supreme goal,

The ultimate is nirvana.

The emptiness of it,

Is the emptiness of absolute.

[6:190] To avert fixation

Of those holding nirvana as an entity,

Absolute wisdom was taught as

The emptiness of absolute.

Verse 6:191

(7) Emptiness of compounded [t = 0:37:28] [MAV PDF page 299]

The 7th emptiness is ’emptiness of compounded’. As we know, the Shravakayana accepts that all compounded (or conditioned) phenomena are impermanent. But here we want to emphasize that they are also emptiness. Because if we don’t emphasize that, we may end up with some truly existing substantial base that could be used to develop an idea of truly existing self, just like the point-like atoms that we talked about last week. So to establish the emptiness of phenomena, the Buddha taught that all phenomena, in other words the entirety of the ➜’three worlds’ (the desire realm, form realm and formless realm), are all emptiness.

[6:191] Arising from conditions,

The three worlds were certainly explained as compounded.

The emptiness of this

Was taught as emptiness of the compounded.

Verse 6:192

(8) Emptiness of uncompounded [t = 0:38:04] [MAV PDF page 299]

The 8th is ’emptiness of the uncompounded’. Some shravakas believe that nirvana or cessation is uncompounded. And similar to what we said before with the 6th emptiness, Rinpoche said this also applies to things like luminosity, awareness, clear light mind – any time we convert any of these into a phenomenon, we end up developing a subtle clinging. So once again it’s good to notice one’s own relationship to these supposedly holy, precious, exotic aspects of the path.

[6:192] [All phenomena] are created, dwell and are impermanent,

Are [inherently] non-existent, thus being uncompounded.

This emptiness

Is emptiness of the uncompounded.

Verse 6:193

(9) Emptiness of limitless (what is beyond extremes) (i.e. the Madhyamaka) [t = 0:38:45] [MAV PDF page 300]

The 9th emptiness is ’emptiness of the limitless’ or ’emptiness of what is beyond extremes’. This is taught to counter clinging to the Madhyamaka path itself.

[6:193] Whatever has no limitations

Is said to be beyond limits;

It is in itself emptiness,

Explained as emptiness of the limitless.

Verses 6:194-6:195

(10) Emptiness of what is without beginning or end (i.e. samsara) [t = 0:38:55] [MAV PDF page 300]

The 10th is ’emptiness of that which is beginningless and endless’, in other words samsara. This is taught to dispel clinging to samsara as truly existing.

[6:194] Because the two extremes of beginning and end

Do not exist, samsara

Is said to be without beginning or end –

With neither coming nor going, like a dream.

[6:195] Therefore samsara is said to be empty of itself,

Without beginning and end,

It is known as empty.

As explained with certainty in the scriptures [the Mulamadhyamakakarika].

Mipham’s commentary here might be helpful for some of the debates that are ongoing about rebirth. He said:

Samsara is said to be without a beginning or end. It is also without duration. In samsara, there is no (real) going (from one life to a later life) and no coming (from an earlier life to the present life)—all is but a dreamlike appearance.

Verses 6:196-6:197

(11) Emptiness of what should not be discarded (i.e. the Mahayana path) [t = 0:39:41] [MAV PDF pages 300-301]

The 11th is ‘the emptiness of non-discarding’. I prefer the Padmakara translation, ‘the emptiness of what should not be rejected’. Here we’re referring to the distinctions between virtue and non-virtue on the path. We’re trying to eliminate our attachment to virtue. Rinpoche has talked a lot in the last couple of years about ‘bad Buddhists’, and warning about our tendency to become overly moralistic and holier than thou as Buddhists. If we do that, it becomes a very big obstacle for our path, as we discussed previously in verse 2:3. When we talk here about rejecting the non-virtuous and holding onto the virtuous, we are referring to the Mahayana path itself.

[6:196] To discard means to disperse,

To throw out – so it is firmly defined.

To retain is to not discard,

[Mahayana] is what is never discarded.

[6:197] The non-discarded suchness

Which is empty of suchness,

Is therefore

Called the emptiness of non-discarding.

As we’ve seen before, any idea of virtue or non-virtue is itself empty. And so when we talk about purifying what’s non-virtuous, actually the ultimate purification is realizing there is nothing to purify in the first place. So normally in the dualistic path, we would confess when we are wrong, when we have done something bad or unethical, but in the nondual path we confess when we’re dualistic. So this is perhaps not the time, but I wanted to quote just a little bit from a lovely practice called the Narak Kong Shak, which is a Vajrayana confession practice. And if you know this, if you’re a Vajrayana practitioner, the section on ‘Confession of the view’ is quite wonderful, and really great to read now that we’ve been studying the Madhyamaka a little. And for those of you who don’t know this, I felt this would maybe establish some kind of auspicious connection to the world of nondual practices. So I’d like to read a couple of verses:

[From Narak Kong Shak]:

Dharmadhatu itself is simplicity.

Seeing it as the duality of existence and nonexistence—how exhausting.

Clinging to things and their qualities—how depressing.

We confess this in the expanse of simplicity, great bliss.

As Samantabhadra is free from being good or bad,

Seeing him as clean or unclean—how exhausting.

Clinging to the duality of good and bad—how depressing.

We confess this in the expanse of Samantabhadra, great bliss.

Equanimity is free from being large or small.

Seeing it as oneself and others—how exhausting.

Clinging to the duality of large and small—how depressing.

We confess this in the expanse of equanimity, great bliss.

Bodhicitta is free from birth or death.

Seeing it as this and future lives—how exhausting.

Clinging to the duality of birth and death—how depressing.

We confess this in the expanse of unchanging deathlessness.

[© Vajravairochana Translation Committee, 2013]

If you know this practice, I really encourage you to consider it as something you might practice for the remaining weeks of this program.

Verses 6:198-6:199

(12) Emptiness of true nature [t = 0:43:03] [MAV PDF page 308]

The 12th is the ’emptiness of true nature’. Here the point is that the Buddha didn’t make up or invent the ultimate essence or nature of phenomena, he just pointed out what was there. Now the challenge is that our opponent might say “Well if it was there already, it’s uncontrived, so maybe we should just admit it’s truly existing.” So we need to combat belief in the truly existing emptiness of emptiness or the potential clinging to the nature of phenomena or the uncontrived nature of the mind. That is why this 12th emptiness is taught.

[6:198] The essence of the composite –

Has not been fabricated

By the [shravaka-] disciples, the pratyekabuddhas,

The bodhisattvas or the buddhas.

[6:199] Therefore the essence [of compounded and uncompounded],

Were explained [as empty].

By way of suchness,

Inherently empty.

Again, this is very important advice for Vajrayana practitioners who might develop attachment to the nature of mind. Because if you do that, then your path is no better than the Cittamatra path that believes in truly existing mind, or even a Hindu path that believes in truly existing atman.

Verses 6:200-6:201ab

(13) Emptiness of all phenomena [t = 0:44:02] [MAV PDF page 308]

The 13th is the ’emptiness of all phenomena’. Here we’re including the 18 dhatus and other phenomena we have talked about already, but they’re grouped in a slightly different way here.

[6:200] The eighteen constituents, the six senses,

The related six perceptions,

Form and formless,

All compounded and uncompounded dharmas –

[6:201ab] All these phenomena,

Are empty of themselves.

Verses 6:201cd-6:215

(14) Emptiness of characteristics [t = 0:44:15] [MAV PDF pages 309-312]

The 14th is the emptiness of characteristics. It’s quite a long section, covering fourteen and a half verses from the last two lines of 201 to 215.

[6:201cd] The emptiness of insubstantial [phenomena], including form,

Is the emptiness of characteristics.

It includes all the aspects of ground, path, and fruit, and shows they are all emptiness:

• 6:202-6:204 is the emptiness of ground – things like the five aggregates.

• 6:205-6:209 is the emptiness of path – things like six paramitas, four samadhis, the 37 limbs of enlightenment and so on. All of them are emptiness also.

• 6:210-6:215 is the emptiness of fruit – for example, the Ten Strengths, the Four Fearlessnesses, and the other qualities of the Buddha such as his great compassion and his omniscient wisdom. All of these are also emptiness.

We know this already from Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika and from the Vajracchedika Prajñaparamita Sutra (Diamond Sutra), but in these verses we’re reaffirming that the ground, everything on the path, all of our practices, bodhicitta, and even up to enlightenment and all the qualities of enlightenment – none of these truly exist. And that’s a profound message.

[Ground]

[6:202] Form has the characteristics of taking form;

Feeling is the experiencer;

Perception perceives attributes;

Formation actually gathers [causes and conditions];

[6:203] Perceiving each particular object,

Is the specific characteristic of consciousness.

Suffering is the specific characteristic of the skandhas,

The characteristics of the constituents are like a venomous snake.

[6:204] The senses, so the Buddha taught,

Are the sources of creation.

Being interdependently connected

Is the characteristic of the conditioned.

[Path]

[6:205] Giving is the paramita of generosity;

Discipline is the absence of anguish;

Patience is the absence of anger;

Endeavour is the absence of regret.

[6:206] Meditation has the characteristic of concentration;

Wisdom has the characteristic of non-attachment;

The six-fold paramitas

Have been described as such.

[6:207] The [four] samadhis, the [four] boundless,

And others such as the [four] formless –

With his wisdom of perfect knowledge

He taught these as having the characteristic of immutability.

[6:208] The thirty-seven limbs of enlightenment

Have the characteristic of accomplishing certain [liberation].

The characteristic of [the first door of perfect liberation], emptiness,

Is the absence of entities through the non-existence of objectification [as truly existing];

[6:209] The [second], the absence of characteristics is peace;

And the characteristic of the third, [wishlessness],

Is absence of suffering and ignorance.

Such are the characteristics of the instigators of liberation.

[Fruit]

[6:210] The nature of the [ten] powers

Was completely established [by the Buddha].

The protecting fearlessnesses,

Are in essence extreme stability.

[6:211] The perfect [types of] comprehension of particulars,

Such as memory, have the nature of immeasurability.

To perfectly accomplish the benefit of sentient beings

Is known as great loving-kindness;

[6:212] To fully protect those suffering,

Is great compassion;

[Sympathetic] joy has the nature of joy.

Equanimity is known as being unpolluted.

[6:213] By having a buddha’s uncommon dharmas,

Ten and eightfold,

The Teacher was unmistaken,

Having the characteristic of being unmistaken.

[6:214] The wisdom of omniscience

Is considered to have the characteristic of being direct.

On the contrary, fleeting [cognition]

Is not considered direct.

[6:215] The characteristics of the compounded and

The characteristics of the uncompounded,

Are in suchness emptiness;

Their own characteristic is suchness.

Verses 6:216-6:217

(15) Emptiness of the non-apprehended (unobservable) (i.e. the three times) [t = 0:45:37] [MAV PDF page 312]

The 15th is ’emptiness of the non-apprehended’, which Padmakara translates as ’emptiness of the unobservable’. This refers to the three times, which cannot be found or pointed out – the present moment does not remain, the past is gone and the future is not yet born. The fact that they cannot be found is their unobservability, and this unobservability is also emptiness.

[6:216] The present does not remain;

Past and future do not exist –

With no observation of these

They are known as non-referential.

[6:217] The essence of this non-referentiality

Is absent. This [absence] is

Not continuous, not dwelling, not perishable.

It is the emptiness of that known as the unapprehended.

Verse 6:218

(16) Emptiness of nature without substantial existence (non-things) [t = 0:46:04] [MAV PDF page 313]

The 16th is ’emptiness of nature without substantial existence’, which Padmakara translates as ’emptiness of non-things’. Here we’re referring to dependently arisen phenomena. They arise from causes and conditions, so we already know they don’t truly exist, but we want to make sure we include them as well so our inventory of phenomena is complete. They also are emptiness.[

6:218] Being created from circumstances,

All composite entities are without essence.

In suchness, the composite is empty –

The emptiness of the insubstantial.

Verses 6:219-6:223ab

Condensed classification into four [t = 0:46:28] [MAV PDF pages 322-323]

The next four verses are a condensed classification. Here the Padmakara translation lists the four categories as: (1) things, (2) non-things, (3) the nature itself. And for the fourth, instead of what we have here as the ’emptiness of other-nature’, they say (4) the ’emptiness of the transcendent quality’. Whether or not the buddhas appear, the nature of phenomena is emptiness. That is their transcendent quality. And that transcendent quality is also emptiness.

[6:219] The meaning of “entity” in brief

Is described as the five aggregates.

The emptiness of these,

Is taught as the emptiness of entities.

[6:220] In summary, non-entity

Describes all uncompounded phenomena.

That emptiness of non-entities,

Is the emptiness of non-entity.

[6:221] The absence of essence of a nature,

Is called the emptiness of nature.

Thus because nature is uncompounded,

It is called nature.

[6:222] Whether buddhas appear,

Or do not appear, in reality,

The emptiness of entities

Is widely known as transcendent entity.

[6:223ab] This is the perfect extreme, suchness,

Or the emptiness of transcendent entity.

Verse 6:223cd

Conclusion and scriptural source [t = 0:46:59] [MAV PDF page 323]

The last two lines of verse 223 are a conclusion and a scriptural source, just to emphasize that all of these twenty are taught in the Prajñaparamita Sutras.

[6:223cd] According to Prajñaparamita,

These are the widely known [twenty emptinesses].

This is another link between the Madhyamakavatara and the Heart Sutra. The Prajñaparamita Sutras are very interesting, because there are many versions of remarkably different lengths, ranging from 100,000 lines to 300 lines (see Wikipedia page on ➜Prajñaparamita):

• Shatasahasrika Prajñaparamita Sutra: 100,000 lines

• Pañcavimshatisahasrika Prajñaparamita Sutra: 25,000 lines

• Astadashasahasrika Prajñaparamita Sutra: 18,000 lines

• Astasahasrika Prajñaparamita Sutra: 8000 lines

• Sardhadvisahasrika Prajñaparamita Sutra: 2500 lines

• Saptashatika Prajñaparamita Sutra: 700 lines

• Pañcashatika Prajñaparamita Sutra: 500 lines

• Trishatika Prajñaparamita Sutra: 300 lines, alternatively known as the Vajracchedika Prajñaparamita Sutra (Diamond Sutra)

The longest version of the sutra consists of twelve large books in Tibetan. The 300-line version is called the Trishatika Prajñaparamita Sutra, and is also called the Vajracchedika Prajñaparamita Sutra. So the Vajracchedika Sutra (Diamond Sutra) is actually one of the Prajñaparamita Sutras.

One of the shortest versions is the Heart Sutra, the Prajñaparamitahridaya, and the Chinese version of the text attributed to Xuanzang (玄奘) has only 260 Chinese characters. Despite its condensed form, the Heart Sutra is said to contain the entire meaning of the longer sutras. However, the most condensed version is just one letter – the letter ‘A’. As Karl Brunnhölzl ➜says:

It starts with the usual introduction, “Once the Buddha was dwelling in Rajagriha at Vulture Flock Mountain” and so on, and then he said, “A.” It ends with all the gods and so on rejoicing, and that’s it. It is said that there are people who actually realize the meaning of the Prajñaparamita Sutras through just hearing or reading “A.”

Contemporary scholarship assesses that the oldest of these sutras is the 8000 line version, the Astasahasrika Prajñaparamita Sutra, which dates to the 1st century BCE. According the Wikipedia, the Heart Sutra itself is largely a quotation taken from one of the longer versions, and that it was probably intended as a dharani rather than a sutra:

The text is largely a quotation from the Pañcavimshatisahasrika Prajñaparamita Sutra (Perfection of Wisdom Sutra in 25000 lines) and it appears to have been composed in Chinese from a translation by Kumarajiva, and then later translated into Sanskrit. The text was probably intended as a dharani rather than a sutra. According to Huili’s biography, Xuanzang (玄奘) learned the sutra from an inhabitant of Sichuan, and subsequently chanted it during times of danger on his journey to the West (i.e. India).

A dharani is like a long mantra. Dharanis are often chanted to protect oneself from malign influences, from calamities and so on. And I think it’s quite apt that it was considered a dharani for chanting, because now the Heart Sutra is very frequently chanted by Buddhists throughout China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and in Tibetan Buddhism as well. We’ll come back to it in a minute.

Verses 6:224-6:226

Summary of the qualities attained [t = 0:49:55] [MAV PDF pages 324-325]

With verse 223, we have reached the conclusion of the argument, and the last three verses of Chapter 6 are a summary of the qualities obtained by the 6th bhumi bodhisattva.

[6:224] Through the illuminating light of wisdom,

As clear as a myrobalan fruit held in his own hand,

He realizes the three worlds as originally uncreated,

And through conventional truth proceeds to cessation.

In verse 224, the bodhisattva on the 6th bhumi realizes the ultimate truth, and sees it as clearly as the kyurura fruit, which in Sanskrit is called the amalaka or amla for short. Some plants produce amalaka that are almost transparent, and if you hold one in your hand, you can see the lines of your hand through the fruit. This is meant to indicate the way that the bodhisattva can completely see ‘through’ phenomena and see their empty nature. So, although on the ultimate nature there is nothing to enter and no-one who enters, in conventional truth the sixth bhumi bodhisattva enters into cessation.

This amalaka fruit has an interesting story. It is a real fruit, from a tree called the emblica myrobalan, Phyllanthus emblica. This tree has quite a history in India and is considered sacred by the Hindus, because the god Vishnu is believed to dwell in it. The tree actually has its own Hindu holy day called Amalaka Ekadashi. Hindus also believe that amla is said to have originated from drops of amrit – the drink that grants the gods immortality – that spilled onto earth accidentally when the gods and demons were fighting after Kshirasagara manthana (the churning of the Ocean of Milk). It is traditionally believed that because the amla originated from drops of amrit, it cures every disease and extends life. The amrit is said to have spilled onto four places, and the Kumbh Mela is celebrated at these four places every 12 years for this reason. People believe that after bathing at these places during the Kumbh Mela you can attain moksha. And the amalaka fruit is also auspicious in the Sanskrit Buddhist tradition, as half of one of these amalaka fruits was the final gift given to the Buddhist sangha by the great Indian Emperor Ashoka. And so I think it’s quite appropriate that Chandrakirti chose it as the example here, not just because of its transparency, but because it has all these auspicious resonances in the tradition.

Verse 225 describes how the 6th bhumi bodhisattvas realize conventional truth. So although their minds rest in cessation, that does not mean they turn away from sentient beings. Indeed, their relative qualities shine forth ever more strongly. And even for ourselves in ordinary life, we know that when we’re less caught in our dualism and our own reactivity, we are better able to be there for others. We are more able to make wise and compassionate decisions.

[6:225] Even though his mind is always dwelling in cessation,

He generates compassion for unprotected sentient beings.

Later, all shravakas and pratyekabuddhas without exception

Will be defeated by his mind.

So as the bodhisattva completes the 6th bhumi and enters the 7th bhumi, he finally outshines the arhats and pratyekabuddhas. Verse 226 describes how with his qualities of wisdom and compassion united, the 6th bhumi bodhisattva is like the king of swans. On the broad wings of the two truths, which correspond to the profound view and the vast activities of conventional truth, he soars ahead of lesser birds – meaning ordinary beings, and also the shravaka arhats and pratyekabuddhas – and flies to the far shore. I find this verse very lovely:

[6:226] Spreading his broad wings of [the truths of] concealment and suchness,

Leading the swans of [ordinary] individuals, this king of swans,

Soars ahead on the strong winds of virtue,

And proceeds to the supreme far shore of the Victorious Ones’ qualities.

I’d also like to offer you the Padmakara translation of this verse:

[6:226] And like the king of swans, ahead of lesser birds they soar,

On broad white wings of relative and ultimate full spread.

And on the strength of virtue’s mighty wind they fly

To gain the far and supreme shore, the oceanic qualities of Victory.

With this, we have finished Chapter 6.

The Madhyamakavatara and the Heart Sutra [t = 0:54:02]

We’ll now turn to the Heart Sutra, but first I’d like to offer a few points of summary to remind us of some of the connections between the Madhyamakavatara and the Heart Sutra:

• The Madhyamaka teachings are based on the Prajñaparamita: As we learned in 6:223, the teachings on emptiness and nonduality in the Madhyamakavatara and Chapter 6 in particular are based on the Prajñaparamita Sutras, the shortest version of which is the Heart Sutra.

• The Mahayana fully teaches both kinds of emptiness: What makes the Mahayana path a greater path – and indeed as Mipham says, the only sole final path – is that it fully establishes both the emptiness of phenomena and the emptiness of the person, unlike some lower Buddhist paths that only fully establish the emptiness of the person,

• 16 or 20 kinds of emptiness: In particular we saw there are 16 or 20 different kinds of emptiness which list all the ways in which phenomena are empty, including the emptiness of form and all aggregates (verse 6:183) and the emptiness of emptiness itself (6:185-186).

• The emptiness of emptiness: in the Heart Sutra we not only hear that “form is emptiness”, but also that “emptiness is form”, which is a beautiful expression of the emptiness of emptiness. And because of this, the Mahayana teaches that it’s very important not to put nirvana above samsara, because if we do that then we’re introducing some kind of dualism, some kind of preference, which ends up becoming an extreme view that will block our path.

• The two truths: the final verse of Chapter 6 emphasizes that the Madhyamaka path is based on a correct realization of both of the two truths (the ultimate and conventional): the king of swans flies on his broad wings of the two truths of profound view and vast activities.

The Buddha’s teaching: nobody can hear the truth (it cannot be spoken) [t = 0:55:32]

As we discuss the Heart Sutra, I’m going to extract a few elements from Rinpoche’s teachings on the Prajñaparamita in Kathmandu, from April-May this year. Rinpoche gave a lovely teaching on the famous passage describing how right after the Buddha’s enligthenment, he decides not to teach what he has realized. This is from the Ariyapariyesana Sutta (The Noble Search, ➜MN 26):

This Dhamma that I have attained is deep, hard to see, hard to realize, peaceful, refined, beyond the scope of conjecture, subtle, to-be-experienced by the wise […] What is abstruse, subtle, deep, hard to see, going against the flow — those delighting in passion, cloaked in the mass of darkness, won’t see. As I reflected thus, my mind inclined to dwelling at ease, not to teaching the Dhamma.

(MN 26)

As Rinpoche put it, the Buddha said “I found a truth that is profound, brilliant, deep, vast, infinite – but nobody’s going to be able to understand it, so I’ll keep quiet in the forest”. Now our first instinct might be to hear this as the Buddha implying he didn’t want to teach. And the traditional story supports this interpretation, as then the gods Brahma and Indra came to request and persuade the Buddha to teach, and they gave him a conch and so forth, and then he taught the Four Noble Truths in the Deer Park at Sarnath.

But actually, as Rinpoche said, if we consider this statement more carefully, we see that with these words the Buddha has already given his first teaching. When he says, ‘Nobody can hear this teaching, so I won’t teach it’, it’s not so much that he doesn’t want to teach. He’s saying that emptiness, the nondual Prajñaparamita that he has realized, is beyond words and so he cannot teach it. It’s not that he doesn’t want to, it’s that he can’t. As Rinpoche says, this is a very beautiful teaching, because right from the beginning, even before the Buddha teaches the Four Noble Truths – traditionally considered his first teaching – he has already indicated that he won’t be able to teach nonduality directly, because it is beyond concepts and beyond words. So this non-teaching is actually a wonderful teaching on nonduality and the emptiness of emptiness.

The ‘dark night of the soul’ [t = 0:57:26]

But if the Prajñaparamita is beyond concepts and beyond words, how are we supposed to make sense of it? How are we supposed to integrate it into our lives? This brings us back to the Heart Sutra and to the question that Shariputra asks Avalokiteshvara, “How to practice the profound Prajñaparamita”? This is also our challenge, because we now know intellectually that everything is emptiness, but we don’t know what to do with that knowledge. Initially we might be very excited by the possibility that we can change our narratives, that we can reinterpret and reinvent ourselves as a Bodhisattva or even as a deity, but then it all comes crashing down. If everything is emptiness, how should we act in the world? How can we make any decision about which way to turn? We’ve dissolved all ideas of good and bad, so how do we know what’s good and what’s bad? Maybe we’ve established a new idea of the self as someone on the Dharma path, we’ve taken refuge, we’ve taken our Bodhisattva vow and maybe we even visualize ourselves as deities, but again why are we doing this? What is the point if it’s all empty?

Rinpoche tells the traditional Mahayana origin story that when the Heart Sutra was first taught at Vulture Peak Mountain, the audience included 500 shravaka arhats who were so shocked at what they heard that they supposedly had heart attacks, vomited warm blood and died. He says this story is sometimes told in a spirit of sectarian pride, but that’s not the message (page 12):

Petty-minded people like us might use these stories to boost our ego because we follow the Mahayana, but this would be a mistake, as the story is actually praising the shravakas! Their shock means that at least they understood something, whereas we are so dumb that it does not touch us.

If you’re feeling disoriented or upset at hearing these teachings, that may be because you’re actually thinking about what they mean for your life, rather than simply engaging with them at an intellectual level. When Rinpoche answers questions, he’s always particularly happy when students ask questions that come from a place of contemplation and practice, not just intellect. I’d like to encourage this kind of engagement with the Madhyamaka: where you’re seeking to apply it to your work, your relationships, your life. Especially for those of us who live in the world rather than in a monastery, unless we are trying to apply these teachings in our daily life, there’s little chance that our habitual thoughts and emotions will change. Our self-image and self-clinging are very strong. Our current Theory-in-Use is very strong. These are no ordinary habits, and we know how much emotion comes when we try to change even ordinary habits.

But if we’re following the path of the Middle Way with sincerity and commitment, then as we saw earlier when we talked about the Hero’s Journey, at some point we enter ‘the dark night of the soul’. We’re lost. Our direction is unclear and our destination is unknown. By the way, I know the phrase ‘the dark night of the soul’ might suggest something negative, but actually the original poem by the 16th century Catholic mystic St John of the Cross, La noche oscura del alma, is about the journey of the soul to the mystical union with God. It’s called the ‘dark night’ because darkness represents that idea that the destination, in this case the soul’s union with God, is unknowable. The unknowability of God is expressed in very similar terms in the classic 14th century mystical text, The Cloud of Unknowing. And something very similar is happening now as we embark on the Middle Way and contemplate the ‘destination’ of nonduality.

Once we have dissolved our rationality and our stories, we end up with the ‘cloud of unknowing’ described by Jigme Lingpa:

As soon as we talk, it is all contradiction;

As soon as we think, it is all confusion.

When we become practitioners, we invent a new idea of our ‘self’, a new life story that is a Dharma story. But our Dharma story is nevertheless just a story. And we’ve just seen how at the end of Chapter 6, Chandrakirti has refuted the ground, the path, and the fruit. He showed that all of them are just emptiness. None of them truly exist. So we really have to confront the danger of nihilism, and we have to find a way of working with this emptiness, this Prajñaparamita. It’s a big challenge, and many of you are experiencing the emotional impact of engaging seriously with this path – it doesn’t just feel like ‘the rug has been pulled from under your feet’, as the English saying goes, but that the whole ground, the earth that has been beneath your feet since the day you were born, has melted into air. It’s not a surprise that you might be feeling disoriented.

How to practice the profound Prajñaparamita [t = 1:00:04]

And that brings us to the Heart Sutra, because Shariputra is asking the same question that all of us are asking, “How should a son or daughter of noble family train who wishes to practice the profound Prajñaparamita?”. He’s facing the same problem. He likewise has dissolved all of his concepts, and now he doesn’t know how to practice. He doesn’t know, because as we’ve just discovered there are no bearings any more. It’s an interesting question because he’s not asking, ‘How should I meditate? How should I dwell in emptiness?’. He’s asking, ‘How should I practice this in my life?’ As Rinpoche said, ‘How should I live by and act according to the Prajñaparamita?’ Shariputra is not just looking at meditation, he’s looking both at meditation and post-meditation.

Rinpoche talked a lot during the Kathmandu teaching about how one of the challenges with this question is that there is no answer in Buddhism about how one should act and the kind of lifestyle one should follow as a Buddhist. We have everything from monks that shave their head and take that extremely seriously, to sadhus who grow their hair long and take that extremely seriously. And they’re both Buddhists and we cannot say one is right and one is wrong. We don’t have clear guidance on how our action should look. The only way to know the right path is through the view.

I think another problem many of us face is that our meditation and post-meditation have become very separated. We may do one thing when we’re on our cushion, but when it comes to actually bringing emptiness into our lives – we don’t know what to do. It’s a little bit like the bodhisattvas on the bhumis: during their meditation time, we can’t distinguish them, but during their post meditation time, they’re very different. And what they’re actually doing on the bhumis is successively finding a way to make their post-meditation more like their meditation. Until finally when they attain the stage of the Buddha there is no separation, no distinction anymore between meditation and post-meditation.

So what can we do if we are facing this kind of question? Some of you have asked me to say something about my own journey through these teachings. For years I was stuck in this same place. I would ask Rinpoche, “If everything is emptiness, how should we decide what to do in the world? If everything is emptiness, how can we even practice compassion? Because we cannot say that one path of action is truly any better than any other path”. I could see no way to choose a preferred way of living, a preferred thing to do with life. I think perhaps I wanted some kind of ultimate purpose, some validation that I was doing something worthy or good, perhaps that I was being a good bodhisattva or something. I’m not really sure I can say any more.

If you look at bookstores, magazines and websites nowadays, they are overflowing with advice on happiness, self-help, and positive psychology. And so much of it is about discovering and then following our passion, our life purpose, as if it is somehow lying buried under the ground for us to discover. It’s a very eternalistic perspective, founded on a deep insecurity. And of course as followers of the Middle Way, we are hardly going to fall for simplistic answers and narratives that supposedly “resolve” the existential questions of life. These kinds of answers might bring some temporary comfort to beings roaming endlessly in samsara, but we know that all ideas of self are baseless – and all narratives we might choose to tell about our passion and purpose are equally empty.

So yet again it comes back to practice. There is really no antidote for this central existential question, except to keep practicing. We just have to work through it until we dissolve all of our imputations. Because all of these questions, doubts, and concerns are just imputations. Over the years I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen Rinpoche get questions like this, and he’s basically always answered, ‘Just keep doing your practice’. I’ve always loved the way he explains how to understand the ultimate, relative and conventional truths (a version is on page 166):

Ultimately, refute all views;

Relatively, accept everything without analysis;

Conventionally, do your practice.

Meditation I [t = 1:04:23]

With that in mind, I’d like to take a moment to do some practice. We’re going to do a brief meditation, very similar to what Rinpoche taught in Kathmandu. If you happen to be listening to the audio while you are driving, please be careful.

Wherever you are, watching or listening to this, take a moment to get a sense of your environment. Now find something in front of you to look at. Whatever.

Just be aware of that. Actually, if you can, be aware that you’re doing that.

[10 seconds]

Okay, did you do it?

As Rinpoche said, this has nothing to do with sitting straight. He said it’s so disheartening when people think that’s what practice is about. He said ‘It’s a poverty mentality. Do what you want. Scratch, yawn, cough, get confused if you want’. The only thing that matters is, did you know what you were doing as you were doing it? If you did, you should trust it. Yes, it’s only a short moment, but you have actually done it. You were aware of what was happening right now in the present moment. It wasn’t some later memory, like some of the Shravakayana mindfulness practices. Here we’re saying meditation is just knowing what is happening. And if you did that, you should consider it was a good meditation. Don’t worry about having to do it 24 hours at a time. And why is meditation important? Because in that moment you were not distracted. Okay, we’ll come back to this later.

All five aggregates are emptiness [t = 1:06:02]

Let’s return to the text of the Heart Sutra. After Shariputra asks his question, Avalokiteshvara replies: