Alex Li Trisoglio

Madhyamakavatara Week 7: Applying the View in Practice

Week 7: Applying the View in Practice: Enlightenment & Meditation

19 July 2017 / 136 minutes

Question: How can we understand enlightenment as nondual? How should we apply the view in our meditation / practice?

Reference: Madhyamakavatara verses 7:1 – 11:56

Transcript / Pre-reading / Audio / Video

Introduction: Review of Week 6 and summary of Week 7 [Audio/Video timing: t = 0:00:04]

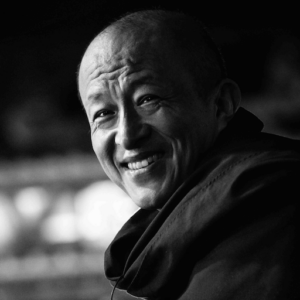

Hello. I’m Alex Trisoglio, and I’d like to welcome you to Week 7 of “Introduction to the Middle Way”. I’d like to begin with a brief review of what we covered last week:

• We established the Mahayana view of emptiness of emptiness. As we saw, it’s not just the refutation of true existence as in the Shravakayana, but a refutation of all four extremes of existence, non-existence, both and neither. Beyond all extremes, true non-duality.

• We also touched on what non-duality might look like in practice, and we contrasted what might be a dualistic approach to emptiness meditation as compared to a true nondual practice. We saw that dualism was focussed on deconstructing the object, whereas non-duality was where both subject and object dissolved.

This week we’re going to talk about the remaining chapters in the Madhyamakavatara, from Chapter 7 to Chapter 11, which will include a discussion about the qualities of enlightenment and also how we perceive the manifestation of the Buddha. This is important for practice, because for many of us, our ideas of practice depend on our idea of the goal – the way we think of Buddha, the way we think of enlightenment. It’s very important to make sure we don’t have an incorrect view, especially a dualistic view. And now that we have established the view, we’re going to talk about how we might apply this view in our practice. That’s what we’re going to do in the second half of the teaching this evening.

Reaching the Source [t = 0:01:54]

As usual, we’ll start with the 10 Bulls. This time the 9th Bull:

9. Reaching the Source

Too many steps have been taken returning to the root and the source.

Better to have been blind and deaf from the beginning!

Dwelling in one’s true abode, unconcerned with that without –

The river flows tranquilly on and the flowers are red.

Comment: From the beginning, truth is clear. Poised in silence, I observe the forms of integration and disintegration. One who is not attached to “form” need not be “reformed.” The water is emerald, the mountain is indigo, and I see that which is creating and that which is destroying.

So as you can see, we’re coming back into the world. We’re returning to naturalistic imagery, and indeed back to the mountain. The mountain is once again mountain. But this time, we see it completely differently, even though it’s still indigo as before. Whereas before we saw forms, now as the verse says, we see “the forms of integration and disintegration”. We see it completely differently.

In terms of the Hero’s Journey, last week was the apotheosis – we reached non-duality. We can’t go any deeper, there’s no further place to go into non-duality. We’ve reached ‘no words, no concepts’. We’ve found our gift, the boon that the Hero finds on the journey. Now we’re ready to bring it back to our ordinary world. In our case the gift is the view of non-duality, the view of emptiness, and we’re going to bring it back in two ways:

• Practice (‘meditation’): This week we’re going to offer it as a gift to ourselves, and we’re going to see how it can benefit us in our practice. This is benefit for self.

• In the world (‘post-meditation’): Next week we’re going to look at how we can share this gift more broadly in the world, which is the benefit for others. That is also practice, but it’s much more about everyday life. And as many of you have commented, in everyday life practice, the path is everywhere; there’s no need to restrict it to our cushion. And indeed the best practice is when we take it beyond our cushion and into the rest of our lives. So next week we’re going to be talking about that.

The other big shift we’re going to see this week is the shift from object to subject. In most of the previous weeks, we have been speaking analytically and objectively about truth, and even when we were analyzing the self, we were largely analyzing the self as an object. We were looking at it in terms of phenomena, aggregates, things like that. This week as we turn to practice, we’re going to shift to transforming the subject. The direction of our gaze is going to change.

Not confusing view and path [t = 0:05:16]

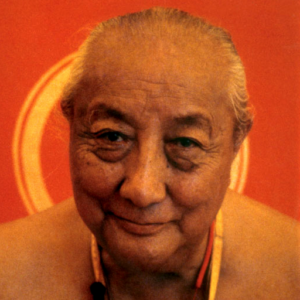

I’d like to say a few more words about not getting caught in the confusion between view language and path language. I know we’ve touched on this before, but I have noticed that especially in some of the online discussions in the Forum, there’s a lot of this kind of confusion. This is completely normal, as Rinpoche says.

I’m going to quote a few words from a teaching Rinpoche gave on view and path in 2011. He was responding to a question, ‘If everything is emptiness, why do we need to practice?’ He said:

This question is very similar to the question ‘If everything is emptiness, then my headache is also emptiness. So why do I need to take a paracetamol?’. Yes, everything is emptiness, but until you have realized this, you still need to apply the antidote. Indeed if you are feeling or experiencing that you have a headache, that somehow shows you have not realized emptiness yet. You only know it intellectually. So you have to deal with your habit, which means you have to apply the remedy. For us practice is the same. Dharma students always ask these kinds of questions, they bring theory and the view of emptiness but they ask practice questions. If you’re having an hallucination, then in theory the hallucination is an hallucination, it does not exist. But because of our habits and our ignorance, most of us don’t even know it’s an hallucination. And even if we know intellectually, it does not mean that we won’t be bothered by it.

We’re going to see this general theme a lot this week, this idea that we tend to over-intellectualize non-duality. Even though we know that non-duality is beyond words and beyond concepts, we still have a deep-seated habit of trying to cling to it and grasp on to it through intellectual means, with our intellectual minds. That’s an obstacle we’re going to have to overcome.

Another question Rinpoche responded to was, ‘If samsara is emptiness, why abandon it?’. He said:

Yes, of course, theoretically there is no need to abandon samsara. Nagarjuna said, “there is no samsara to abandon, there is no nirvana to be attained.” These statements are good, but you have to realize their meaning. And realization is not mere intellectual understanding, or even experience. You have to actually realize. The masters of the past have said that understanding is like a patch on a piece of cloth – it will sooner or later fall off; experience is like mist in the morning – it will soon disappear. You can never trust them. So the only way is to practice until you have realization.

As Rinpoche said, ‘I guess it’s kind of understandable that people get mixed up’. So what might we do? Here are some suggestions:

• Don’t apply ultimate analysis to the relative: As we know, as soon as we analyze relative truth, it is going to fall apart. That’s why Jigme Lingpa said:

“As soon as we talk it’s all contradiction;

As soon as we think it’s all confusion.”

As Rinpoche says, ‘practice, especially in the vajrayana, does not make logical sense.’ If we try to analyze our practice, it’s going to fall apart. We won’t find rational answers.

• Remember that all conventional truths are ultimately untrue: They are at best approximations and shared narratives among limited groups of people. So don’t get too caught up in trying to fine-tune conventional truth. It’s never going to be perfect, it’s never going to be precise.

• Remember Rinpoche’s advice about view and path:

“Ultimately refute all views.

Relatively accept everything without analysis.

Conventionally, do your practice.”

Overcoming blocks to our practice [t = 0:09:05]

This advice “Conventionally, do your practice” is very simple, and yet it’s not so easy to put into practice. If we could just trust it, and if we could just actually do our practice, all our other doubts, all our other problems, would take care of themselves. If we really did 10,000 hours of hearing, contemplation and meditation, the teachings would soak into us. They’d become part of our narrative, our map of the world. They’d correct the problems in our existing maps. Likewise, if we really seek to go beyond mere understanding, and even beyond flashes of experience, to genuine realization – as we put in the time, our progress won’t merely be intellectual. Our Theory-in-Use will become different. It will shift. And once we’re strong practitioners, the teachings are described as reaching a state ‘like a thief entering an empty room’. At that point, even if there are doubts, or thoughts, or distractions, whatever may come up during our practice or during our daily life, none of that is going to knock us off our path of practice, it’s not going to distract us.

Really the important point here is to do our practice. We’re not trying to become scholars. You can have the most sophisticated intellectual understanding, but your practice is only as good as your Theory-in-Use – what’s driving your actual perception and action. Unless you change that, mere intellectual understanding is useless to you. So we know we need to practice, but we don’t do our practice. It’s like a patient who has a sickness and the doctor has given them the medicine and they won’t take it. Remember from Week 1, the story of the man who’d been shot with a poisoned arrow, and he refused to let the doctor treat him and remove the arrow, until he knew everything about where the arrow had come from. So that’s the kind of mindset we don’t want to fall into.

And it applies both to beginners – many beginners never actually start practice, because they’re so busy debating and doubting and being skeptical – and also to many people who have been around the Dharma a long time who can also become ‘Dharma stubborn’, as Rinpoche calls it. They’re like old leather, which is really hard. The Dharma cannot penetrate them any longer. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche called this spiritual materialism. Or there’s a version of this with seasoned Dharma students who just want to debate all day long, and never get around to practice. Whatever our version is of avoiding, or procrastinating, or just generally not doing our practice, we need to deal with it.

Now as beginners, maybe it’s just a lack of discipline or being too easily distracted, but it’s relatively easy to fix. We just have to deal with our own laziness. As Rinpoche says, ‘The best way to develop discipline is just to practice being disciplined’. You start in small ways, even just committing to five minutes of practice at a time, and just by making it a habit where you don’t break your commitment, you will slowly become more disciplined. But there’s a bigger problem if what’s holding us back is doubt about the practice. We might wonder will these exotic practices actually help, or does this view of non-duality have anything useful to say in our lives?

The Three Fetters and doubt [t = 0:12:37]

You may recall right at the beginning of the text, in Chapter 1 verse 6, we talked about the ‘Three Fetters’. This term comes from some Pali suttas, including the Sangiti Sutta and the Dhammasangani, and it refers to three things that get in the way of our practice:

• Belief in a self.

• Attachment to rites and rituals, attachment to practice.

• Doubt.

If we have either of the first two – belief in a self and attachment to rituals – then obviously we’ll be practicing wrongly. Hopefully by now we have enough of an understanding of non-duality that at least we can catch ourselves if we start falling into either of those.

But doubt is different, because if we have doubt then we may not even start to practice. As Rinpoche said, this is really one of the biggest problems for practitioners, in terms of not being able to decide what is the right path, and not trusting the path. The Sanskrit word that we’re translating as ‘doubt’ is vichikitsa (Sanskrit: vichikitsā, विचिकित्सा, Pali: vicikicchā; Wylie: the tshom, Tibetan: ཐེ་ཚོམ་), which is defined as ‘being of two minds about the meaning of the Four Noble Truths’. Basically it means we don’t end up getting involved with wholesome activities, such as accumulating merit or doing as our practice. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche said, ‘It means you don’t trust any possible alternatives. You don’t want advice. You don’t want a way out. You doubt the teachings, the teacher, the Dharma, even the norms of everyday existence.’

Now of course there are some people who have good karma, who don’t get caught in doubt. When we talked about the three kinds of students, that’s the first kind. But among Westerners, especially educated Westerners, especially those with skeptical or critical minds, it’s very easy for us to get very caught in our own views, our own justifications, our own questions. We can’t even see that we have a biased view.

So I just want to encourage you, if for whatever reason you’re not practicing, I hope the last six weeks have been enough to at least dissolve some of your resistance, to at least give it a try. And if you are practicing, then I hope that now you at least have a better sense of the difference between right and wrong practice. I hope you are better able to avoiding getting caught in either nihilism, loss of inspiration, hopelessness and denial of self; or eternalism, which is possibly a bigger problem for many on the Vajrayana path, especially attachment to the path, experiences, the guru, Buddha-nature, and so on.

Rinpoche says we need to find whatever ways we can to inspire ourselves for our practice. That’s why, going back to our discussion of rangtong/shentong in previous weeks, even though the strict emptiness-orientation of the rangtong view is so important while establishing the view; the more Buddha-nature-oriented shentong view is essential for practice. We need to inspire ourselves with beauty, inspiration, song, dance, music, ideas of Buddha-nature, enlightenment, art and grand visions. Yes ultimately all this is going to dissolve, but we need it now. We need it to practice. Rinpoche often quotes Shantideva who points out that yes, of course we want to purify all our ignorance, all our defilements, but ‘the last ignorance we want to purify is the idea that there is enlightenment’. So we might know intellectually that enlightenment does not truly exist, but if we dissolve that too soon, too early in our path, we’ll lose all inspiration. We’ll lose forward motion and momentum.

The paradox of the second mountain [t = 0:16:13]

Let’s go back to the mountain / no mountain / mountain. Now as we’ve said, we started with the mountain in Act I. In Act II we came to ‘no mountain’, we were in the realm of analysis, breaking everything apart. Now in Act III we’re back in the realm of ‘mountain’. Interestingly we’re seeing the mountain as mountain, it’s not some magical golden realm which looks different. And yet nevertheless we see it in a completely different way from how we saw it before. So if we were just to say to someone, ‘well you start with mountain, and you end with mountain’, the average person would ask ‘so then what’s the point in this so-called practice?’. So that’s why we say, ‘you start with the mountain and you end up with these incredible Buddha realms’. Now the average person is more interested when we use language like this. We’re being skilful, we’re working with conventional habits of wanting desirable things, and this is the magic of the path. The more we practice, yes – we do actually see the mountain differently, and we realize this was what was meant by the journey towards enlightenment in the first place. And that very realization means that we don’t need any longer to see it as something magical or golden, because seeing it in its non-dual nature is the magic.

We saw last week that the Middle Way is a path beyond extremes. We spoke of the equality or evenness of samsara and nirvana. We don’t seek to remain in nirvana, nor do we despise samsara. We realize they’re not two separate things. It’s just a conventional designation. Rinpoche said, ‘Nirvana is not the purification of samsara, it’s realizing that there is no samsara’. So they are not separate. We’re not journeying to some different place. We are changing our subject, our awareness, not the surroundings, not the place. This is already a Buddha realm; we just don’t realize it. As Rinpoche said, ‘All the Buddha needed to say was, You are all Buddhas, but none of us would understand what he meant’. We would not get it. And that’s why he had to teach the 84,000 paths. He gave us complexity because we cannot understand simplicity. And then of course with the complexity comes all these problems of doubt, resistance, and not wanting to practice. And then we need further elaborations about the amazing qualities of the Buddha, all these relative teachings, as ways of inspiring us.

Now if we had more merit, none of this would be necessary. We could hear the truth directly. But as Rinpoche said, we should never look down on these provisional teachings, because that’s all we can understand. That’s why these teachings are very much what we need. By the way, when I say ‘understand’, I don’t mean intellectually. I’m sure many of us, if not most of us, we can understand the view, we can probably even gain some intellectual satisfaction as we read Nagarjuna and Chandrakirti alongside Wittgenstein and Heidegger and all the rest, but this isn’t what’s meant here. When we speak of understanding here, we are talking about the awareness that our perceptions and behaviours are not aligned with the view of non-duality. We are talking about self-awareness and understanding the need to practice. We realize that understanding actually means going beyond intellectual understanding to realization. As we have said many times we want enlightenment, not a PhD in Buddhism. Rinpoche will often chide his own khenpos, saying that yes, you have to study to establish the view, but that’s only 2% of the journey. The other 98% is practice. You have to move from establishing the view, the Espoused Theory, to the Theory-in-Use. And no much how much you study and debate, none of that will do this.

Having the best intellectual understanding just isn’t going to be of benefit to ourselves and others. We need to overcome our ego, our self clinging, our habits, our defilements. We need to examine and overcome whatever our habitual explanations might be of how smart, or stupid, or diligent or lazy we might think we are. We need to overcome our precious self-narratives of being wonderful practitioners, or being awful practitioners, or great debaters or unable to understand the teachings, or being important in the sangha or being complete nobodies. Whatever our particular ego trip is, we need to get over ourselves. And the only way to get over ourselves is to practice.

Okay, just a recap. Why do we need the view?

• Choosing the right path: we need the view in order to choose the right path in the first place. We need to differentiate right paths from wrong paths, and to make sure we don’t follow guides or paths with extreme views. And we need a path which is based on the realization of both of the Two Truths. We’ve seen this many times over the past weeks.

• Practicing the path: Once we’ve chosen the right path, then we need to practice the path we have chosen. So we need to use our view to counter and eliminate the Three Fetters:

• Belief in a self: we must learn not to get too attached to our self-narratives as practitioners, or to our experiences in practice.

• Attachment to rites and rituals: of course, we must not get attached to the path.

• Doubt: we need the view to answer all these questions like – ‘If all is emptiness why do I have a headache’, or confusing the Buddha that we meditate on in our deity practice with an Atman or a soul. Or thinking that a non-truly existing self means nihilism. Or getting lost and confused when we get a lack of inspiration. Or when we encounter the problems of the horse and donkey practice we talked about last week.

So to repeat: ultimately refute all views, relatively accept everything without analysis, conventionally do your practice.

Practice is not something ‘additional’ [t = 0:22:28]

We might think, ‘okay, the worst case scenario is I didn’t do my practice today. That’s okay, I can do it tomorrow, maybe I can do it on the weekend’. We see practice as something additional to our lives, but that view is wrong. We are always already practicing something 24 hours a day even now – the question is what? And are we aware of our habits of perception and action? Are we intentional, are we deliberate, are we mindful? Or is this just samsara, the wheels of habit and ignorance just clunking round and round? Without awareness, without choice, and without a deliberate practice, we’re just going to keep reinforcing our existing habits. That’s what we’re practicing – as in, that’s what we’re repeating every day. And as we saw in Week 5, we know from cognitive science that this kind of repetition and practice makes our habits stronger.

So every day that we continue to practice ignorance and lack of awareness, we are just further deepening those characteristics. If we’re honest, most of us are completely caught in the practice of self – self-cherishing, self-promotion, self-narration. Just spend some time online – look at Facebook, look at newspapers, look the web. Selfishness is everywhere, and we know it leads to unhappiness, conflicts, and samsara. And yet most sentient beings don’t know that there is an alternative. But we do. We have met the Dharma, so we know better. Let’s not waste this precious moment, this precious opportunity. Let’s not just continue to reinforce all our samsaric habits. Let’s establish new habits, based on the view of non-duality.

How the view is introduced in different vehicles [t = 0:24:12]

I said a few moments ago that if we had more merit, we could hear the truth directly. I’d like to say a few words on the three different ways the truth is introduced.

• Shravakayana and Mahayana: In the causal path, the Mahayana and the Shravakayana, the view is introduced in two different ways. Firstly, through the Buddha’s words, although of course that only works if you’re a Buddhist. Secondly with logic and reasoning. And as we’ve done in these last few weeks, once we have established the view and gained confidence in the view, that leads us to say, ‘Okay I’m ready, I shall practice this view now, I shall get used to the idea of emptiness’. The path is causal, because the cause is different from the experience of the result, which is Buddha-nature. But once we start to practice, we know that as soon as we see ourselves grasping onto anything as truly existing or real, we can bring back the logic of emptiness to deconstruct that. And as soon as we find ourselves falling into nihilism, we can remind ourselves that the Middle Way is beyond all extremes. So that’s the causal path.

• Vajrayana: In the result path, the Vajrayana, we introduce the result rather than the cause. We introduce what is to be realized through our practice of the view, and now we are beyond language and concepts, beyond rationality, and this indeed is something Western philosophy does not have. We’ve already seen that Western philosophy doesn’t have a path of practice that leads to the realization of emptiness, even in the causal way, but there’s definitely nothing in Western philosophy that corresponds to the result vehicle. How is this done in the Vajrayana? Well, the master will introduce the view by showing you an example of the result, of Buddha-nature. He’ll talk about it, paint it, show you the example. And indeed that’s the whole point for those of you who are doing kyerim (or development meditation, including practices such as deity visualization etc.) – it’s creating an example to identify the view, so you can recognize right view in your own experience, through this example. Now, of course it does help to have established the Mahayana view first, because otherwise you might end up practicing Vajrayana for decades and getting nowhere, because you’re not actually practicing right view. There are too many Vajrayana practitioners that end up practicing extreme views without even realizing it. We cling to experiences, we think of Buddha-nature or rigpa as truly existing. We might fall into the horse and donkey problem as we discussed in Week 5. So having the right view at times like that will really help.

• Dzogchen: The third way, the highest way, is Mahamudra or Mahasandhi (Dzogchen). Here there is no logic. We use no examples. There is no method or object. In mahasandhi the view is established by introducing the view in itself – not with words, not with concepts, not with examples. I can’t say anything more about this now, but I want to emphasize that the view in the mahasandhi is no different from what you would realize if you practiced the view of emptiness that we have established here. The only difference is that it is introduced directly.

I say all this for a couple of reasons. Firstly I really want to emphasize the qualities of the Prasangika-Madhyamaka view. Other paths, even the Svatantrika-Madhyamaka, offer a lot of theory about conventional truth, as we’ve seen in the debates about mind and consciousness and all the rest. But once you get to the result vehicle, in the Vajrayana and especially in the mahasandhi, none of that is going to be relevant, because you are completely beyond any kind of concepts and theories. By contrast, because of the pristine simplicity and clarity of the Prasangika-Madhyamaka, it can be your trusted companion until the end of the journey. If you invest in the Prasangika-Madhyamaka view, you will not need to upgrade it at a later stage.

I also hope to inspire you to do your practice and to practice aspiration so that – if you don’t already have one – you might encounter a genuine teacher, with a genuine lineage who can connect you to these practices.

Verse 7:1

The 7th Bhumi [t = 0:28:25] [MAV PDF pages 341-348]

Let’s turn to the text. We start with the 7th bhumi. I’d like to remind you that on the 7th bhumi, finally the bodhisattva realizes the dignity or the superior understanding of ‘knowing one’s own object’ and therefore he now outshines the shravakas and pratyekabuddhas with his wisdom, not just his merit. So we’ve seen this before in Chapter 1.

[7:1] On [the bhumi of] Far Gone,

[The bodhisattva] enters cessation at any instant,

Brilliantly mastering the paramita of Upaya.

There’s an interesting discussion here in the text about how Nagarjuna and Maitreya interpret the Prajñaparamita differently, in particular how they have different views on whether or not the shravakas and pratyekabuddhas understand the selflessness of phenomena. At first sight, it seems that Nagarjuna and Maitreya disagree, which would indeed be a big problem because they’re both realized beings. But as we discovered during the discussion, it actually turns out they are using two different definitions of the selflessness of phenomena:

• Nagarjuna: When Nagarjuna talks about clinging to the self of phenomena, he means grasping to the five aggregates. We know the shravakas have gone beyond this, because they have to realize the emptiness of the five aggregates in order to realize emptiness of the self of the person. Maitreya accepts this too.

• Maitreya: Whereas Maitreya means something different by clinging to the self of phenomena. He considers that a person still has clinging to the self of phenomena as long as they still have subject, object and action – in other words, tsendzin. And yes, the shravakas still have this, which is why Maitreya does not say they have purified their clinging to the self of phenomena.

Given that they’re both commenting on the Prajñaparamita, why is there this difference? Well, it’s because they are teaching for different audiences. Nagarjuna is teaching for all the yanas, and he wants to inspire everyone to study and practice the Prajñaparamita. Whereas Maitreya is giving exclusive Mahayana teachings in texts like the Abhisamayalankara (The Ornament of Clear Realization), so he sees no need to adapt his teachings for the shravakas, and he also wants to praise the greatness of the Mahayana path.

On page 345, again we repeat that shunyata is only the negation of existence, only the first extreme. Whereas the non-dual emptiness is the negation of all four extremes – existence, non-existence, both and neither. Everything that we covered until Week 6, in other words all the verses in Chapter 6 before verse 6:178 are establishing emptiness as it is taught for all the yanas. In those verses, the only thing we are establishing is the lack of true existence. We do not establish emptiness beyond all four extremes until verse 6:179. On page 348, it’s also important to note that Chandrakirti doesn’t actually teach freedom from the other three extremes in the Madhyamakavatara. So when we look at the twenty emptinesses in verses 6:179-6:226 it is just a list. We need to go to other texts to actually establish these twenty emptinesses.

On page 347, there’s a discussion about two ways of talking about the Third Turning teachings on Buddha-nature and enlightenment. For the schools that talk about the Third Turning of the wheel of Dharma being definitive, they are referring to the teachings on dharmadatu, ultimate reality and the union of clarity and emptiness. By contrast, even these schools would say that when we talk about Buddha-nature in the mindstreams of sentient beings, that is not definitive. That’s always a provisional teaching. So the question arises, why did the Buddha teach an eternal blissful Buddha-nature in the mind stream of ordinary beings? As Rinpoche said, it was taught to inspire people such as Hindus and other non-Buddhists who believe in an eternal self to the Dharma. It is a skilful means or, as Rinpoche said, a ‘trick’ to attract them to the correct Dharma.

Verses 8:1-8:3The 8th Bhumi [t = 0:32:30] [MAV PDF pages 349-357]

The 8th bhumi, the bodhisattva accomplishes the quality of fearlessness. We came across this in Week 6 because it was one of the important qualities of the disciple of superior faculties mi chéwé chöla zöpa töpa (Wylie: mi skye ba’i chos la bzod pa thob pa, Tibetan: མི་སྐྱེ་བའི་ཆོས་ལ་བཟོད་པ ཐོབ་པ་), which means ‘attaining the acceptance of the truth of non-arising’. The contrast here is that shravakas and pratyekabuddhas cannot cope with this nature of the unborn, the non-arising. We’ll talk about this more when we come to practice.

[8:1] In order to attain further increase of virtue,

The great lord enters The Immovable,

So that [virtue] becomes irreversible –

Here [the paramita of] aspiration is exceedingly pure,

And he is roused from cessation by the Victorious Ones.

[8:2] Because a mind free from attachment cannot have any faults.

Defilements and their roots are fully pacified on the eighth bhumi.

While his afflictions are exhausted and he is the supreme of the three worlds,

Still [the bodhisattva] is unable to procure the limitless sky-like wealth of the buddhas.

[8:3] Samsara has been stopped and as he attains the ten powers,

He will manifest in a variety of ways to sentient beings.

Then we talked about the Ten Powers. I’m not going to talk about them in detail, because they are fairly self explanatory. But I’d to say a little about the 5th power, the power of rebirth, as an illustration of the inconceivable power and ability of the 8th bhumi bodhisattva. In introducing the idea of rebirth, Rinpoche talked a little about different kinds of tulkus or manifestations:

• Kyéwa tulku (Wylie: skye ba sprul sku, Tibetan: སྐྱེ་བ་སྤྲུལ་སྐུ་) is a reincarnation, for example of a master or teacher.

• Chinchilapé tulku (Wylie: byin gyis bslabs pa’i sprul sku, Tibetan: བྱིན་གྱིས་བསླབས་པའི་སྤྲུལ་སྐུ་) is a blessed manifestation.

• Zowé tulku (Wylie: bzo ba’i sprul sku, Tibetan: བཟོ་བའི་སྤྲུལ་སྐུ་) is a form manifestation. On the 8th bhumi, the bodhisattva is able to notice when people need things like a bridge or a boat to cross a river and he can manifest as any of these material phenomena: a bridge, a boat, a cool breeze on a hot summer’s day, and so on.

Rinpoche gave a very lovely example of a Casablanca coffee shop. He said, imagine that an 8th bhumi bodhisattva sees that there is a specific coffee shop somewhere in Casablanca and that in the year 2022 someone is going to visit this coffee shop for just a half and hour to get a cup of coffee, but at that moment they will become a perfect vessel for receiving the teachings and connecting to the Dharma. So the 8th bhumi bodhisattva will wait, and then maybe in January of that year, he’ll manifest or maybe bless a waiter or waitress or barista in the coffee shop and then eventually the man walks in and orders a coffee and maybe the barista only exchanges a couple of sentences with him, that’s all. And that’s it, it’s over. The bodhisattva has done his job, he has planted the seed of the Dharma. This example hopefully makes it clear that we have to think in a very vast way about what might be a manifestation of the Buddha’s or bodhisattva’s activities. And when it comes to the notion of ‘benefiting sentient beings’, most of us have no idea what this means. We don’t know the workings of karma, we don’t know which chance encounter is going to benefit someone or bring them to the Dharma. But the 8th bhumi bodhisattva knows this.

On pages 356 and 357 there is a conversation about the Sakya and the Gelug understanding of emptiness, I won’t go through it’s now, as the commentary is self-explanatory.

Verse 9:1The 9th Bhumi [t = 0:35:20] [MAV PDF pages 358-359]

[9:1] On the ninth [bhumi] [the bodhisattva’s] various strengths become perfectly purified,

And he attains the perfect purity of the qualities of [validly] cognizing phenomena.

The 9th bhumi is straightforward, just a reiteration that on the pure bhumis on the 8th through the 10th, the only remaining defilement is nyinang, mere duality. There is no more tzendzin, there’s no more of the subject, object, action. And yet there’s still a sort of pre-conscious, pre-verbal sense of subjectivity and objectivity that the bodhisattva needs to purify.

Verse 10:1

The 10th Bhumi [t = 0:35:50] [MAV PDF pages 360-363]

[10:1] On the tenth bhumi [the bodhisattva] is empowered by all the buddhas,

Receiving holiness, his wisdom becomes even more supreme.

As from rain clouds, for the sake of sentient beings,

The sons of the victorious ones spontaneously rain down Dharma upon the crops of virtue.

The 10th bhumi is also straightforward, and a couple of points came up during the questions and answers. On page 361, Rinpoche was asked whether we can apply emptiness in real time, and he said, ‘No, you can’t’. When there’s some kind of emotion that’s got hold of you, you don’t have time to go through the Seven-Fold Analysis of the Chariot and so forth. You need to have done your practice, as we’ve said many times. It needs to have become incorporated and embodied in your Theory-in-Use, because that’s all you’re going to have accessible to you in the moment.

On page 363, Rinpoche was asked ‘Please speak about compassion’. He gave a beautiful short answer. He said, ‘Compassion is a mind that understands emptiness’.

Verses 11:1-11:11

Chapter 11: Enlightenment [t = 0:36:37] [MAV PDF pages 364-370]

So we now transition to Chapter 11. The first four verses describe the qualities of the 1st bhumi, the 1,200 qualities of the Path of Seeing. You can read the list, it’s straightforward, it’s poetic, but it’s also already beyond us. We can’t really make sense of it, and the numbers just keep increasing in subsequent bhumis until they are truly uncountable.

[11:1] At this time [of the first bhumi], seeing one-hundred buddhas,

And understands he is blessed by them.

He remains for a hundred kalpas on this [bhumi],

Even the end of the last and the beginning of the next [kalpa] is perfectly perceived.

[11:2] This Wise One enters and arises from a hundred samadhis;

He is capable of moving and illuminating a hundred worlds;

Likewise, he is miraculously able to bring a hundred beings to maturation,

And he is able to travel to as many buddha fields.

[11:3] The Muni prince perfectly opens the doors of the Dharma,

Displaying within his single body one-hundred bodies,

And just as every body is endowed with its own entourage

Each of the one hundred has an equal display.

[11:4] Such qualities of the Wise One dwelling on the pramudita bhumi,

Are perfectly achieved in exactly the same way, but thousand-fold

When he dwells on the [bhumi] of Stainless.

[In the following] five bhumis the bodhisattva achieves one hundred thousand [qualities],

[11:5] Then one billion, and then ten billion;

After that, he achieves one trillion followed by

Ten million trillions which again are

Multiplied thousand-fold, all of which he obtains completely.

[11:6] Dwelling on the eighth bhumi, the Immovable [the bodhisattva] has no discursive thoughts.

If one gathered a hundred thousand of the billion fold universe,

All the dust motes these contain

Would equal the amount of qualities he here achieves.

[11:7] Dwelling on the [ninth] bhumi of Excellent Intelligence,

The bodhisattva achieves the previously mentioned [twelve] qualities

[Multiplied] by as many as ten times the dust motes

In a hundred thousand of the infinite [universe].

[11:8] To say the least, qualities on the tenth [bhumi],

Exceed the reach of words.

Were one to describe the indescribable,

They are as many as there are motes of dust.

[11:9] The bodhisattva is able to manifest at any moment,

In every pore of his body, bodhisattvas

Together with perfect buddhas, infinite in numbers,

As well as devas, asuras and humans.

[11:10] As the moon shines brightly in a clear sky,

You strove repeatedly for the bhumi that develops the ten powers.

In the Akanishta buddhafield, you accomplished the aim of all efforts – the level of supreme peace –

With its ultimate and incomparable qualities.

[11:11] As the divisions of a container does not create different space,

Likewise, the various categories of phenomena do not divide suchness.

Therefore when perfectly comprehending one taste,

You excellent Wise One comprehended [everything] knowable in a single instant.

In verse 11, Rinpoche said the bodhisattva understands all phenomena even though there are no phenomena to understand. And he understands in a way that is beyond understanding and what is to be understood. In other words, it is truly non-dual. As Rinpoche said, these qualities are not only difficult, they are beyond us. He gave a lovely example of inconceivability: Imagine you have been in the dark your entire life, and never experienced so-called daytime or sunlight. Then imagine that the so-called sun comes, and everything is bright and shining for the first time. In that moment it will be like a fairytale, because you have never experienced daylight before.

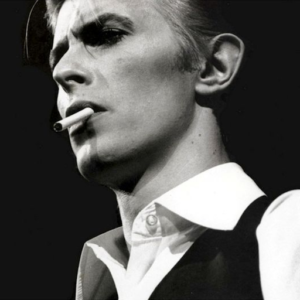

Inconceivability [t = 0:37:45]

That example made me think of a lovely story about inconceivability, which some of you may know. It’s the 1941 story “Nightfall” by Isaac Asimov, the famous science fiction writer, which is about the first time somebody experiences night. It’s about what happens when darkness comes to a planet that’s ordinarily illuminated by sunlight at all times. In 1968, it was voted the best science fiction short story written prior to the establishment of the Nebula awards in 1965. It’s a true classic. According to Asimov’s autobiography, John Campbell (editor of Astounding Science Fiction) asked Asimov to write the story after discussing with him a quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson:

“If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore, and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God!”

Campbell thought the opposite:

“I think men would go mad.”

Here’s the outline of the story:

The fictional planet Lagash is located in a stellar system containing six suns, which keep the whole planet continuously illuminated; total darkness is unknown, and as a result, so are all the stars outside the planet’s stellar system. The story begins when an archaeologist finds evidence of multiple cyclical collapses of the planet’s civilization, which have occurred regularly about every 2000 years.

At the same time, a reporter learns about group known as the Cult (“Apostles of Flame”), which believes the world will be destroyed in a darkness that unleashes a torrent of fire.

An astronomer calculates that once every 2049 years, due to planetary alignment, only one sun is visible in the sky. This single sun is eclipsed by another orbiting body in the solar system, resulting in a brief “night.” His theory is that this “night” was so horrifying to the people who experienced it, that they desperately sought out any light source to try to drive it away: particularly, by frantically starting fires which burned down and destroyed their successive civilizations. He also postulates that the “Apostles of the Flame” started out as vague surviving legends after the last eclipse: small children too young to understand what was happening did not go insane but grew up half-feral in the ruins. As they grew older, the only clues they had to what had happened were the insane ramblings of adults who had lived through the eclipse. Over the centuries, these vague stories became legend, and then a cult of religious devotion.

The scientists realize that another of these eclipses will happen soon. Since the current population of Lagash has never experienced general darkness, the scientists conclude that the darkness will traumatize the people and that they need to prepare for it.

When nightfall occurs, the scientists (who had prepared themselves only for darkness) and the rest of the planet are stunned by the sight of the hitherto invisible stars outside the six-star system, filling the sky. Never having seen other stars, the inhabitants of Lagash had come to believe that their six-star system contained the entirety of the universe. In one horrifying instant, anyone gazing at the night sky – the first night sky which they have ever known – is suddenly faced with the reality that the universe contains many millions upon billions of stars: the awesome realization of just how vast the universe truly is drives them insane. This night sky is filled with stars – it is very different from that of Earth’s, because Lagash and its stars reside in a globular cluster, where hundreds of thousands of stars are visible in the now-darkened sky.

The short story concludes with the arrival of the night and a crimson glow that was “not the glow of a sun.” Civil disorder breaks out; cities are destroyed in massive fires and civilization collapses.

It’s a wonderful story, I really encourage you to read it. It reminds me of the story of when the 500 arhats they first heard the teachings on the Prajñaparamita. I really love “Nightfall” as an exercise of imagination. It is very easy to say that ‘Buddha qualities are inconceivable’. But the word ‘inconceivable’ is almost too simplistic, too throwaway. It doesn’t touch our hearts. We don’t know what it actually means. So a story like this can remind us, wow, if we were to experience something truly inconceivable like this, it would have an emotional shock that we just can’t imagine. It’s always worth bearing that in mind, because as we said already, most of us end up limiting emptiness, nonduality and enlightenment to some kind of narrow intellectual understanding, rather than the infinite vastness of nonduality. This kind of inconceivability is the complete opposite of our limited ideas of emptiness. I want to leave you with that as an example of what the experience of inconceivability might be like.

In his introduction to the Vimalakirti Sutra, Rinpoche also speaks about inconceivability (page 61):

As philosophers, we must learn to interpret accurately and to mean what we say. For example, what do you mean when you say, ‘incredible’ or ‘unthinkable’? Whatever it is, it’s too vague. The only way to understand something fully is to be able to think the unthinkable and, at the same time, let the unthinkable remain unthinkable. If you can do that, you are improving. Right now most of us cannot think the unthinkable. The few who can, quickly discover that being able to think the unthinkable means that the unthinkable is no longer unthinkable, it’s a ‘thinkable unthinkable’. So, bodhisattvas must be able to think the unthinkable while allowing the quality and the taste of ‘unthinkable’ to remain.

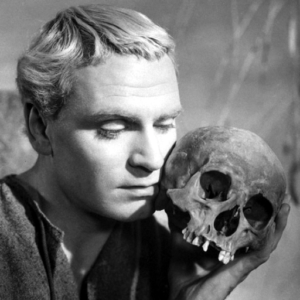

Verse 11:12

An objection [t = 0:42:57] [MAV PDF page 370]

[11:12] If peace is suchness, there is no engaging intellect.

With no engaging intellect, an apprehender of objects certainly makes no sense.

The absence of apprehender contradicts any cognition,

And without any cognition who can teach others, saying, “It is so”?

There’s a doubt raised here in the commentaries about whether the Buddha actually has any activities or manifestations. We know from the previous example of how water is perceived in the six realms, that there is no base for our imputations and projections of phenomena. Many philosophers say that the Buddha qualities and activities are similarly baseless. They’re just the projections of others. Here we are talking about the jñanas and the kayas:

• Jñanas refer to wisdom or non-dual awareness.

• Kayas refer to bodies. In the Mahayana we talk about two bodies or kayas: the dharmakaya and the rupakaya. The dharmakaya is the truth body, which is non-duality beyond all extremes. The rupakaya is the form body, which is all form and manifestation. These two correspond to ’emptiness’ and ‘form’ in the Heart Sutra. When we speak of the ‘Three Kayas’ in the Vajrayana, the rupakaya is subdivided into the samboghakaya and the nirmanakaya. The samboghakaya is the body of mutual enjoyment, the body of bliss or clear light manifestation. The nirmanakaya is the created body, which manifests in time and in space.

Now the problem raised in verse 11:12 is with the vajra-like antidote that we met previously in Week 2. As you may recall, this is the final antidote that removes the last defilement of the 10th bhumi bodhisattva before s/he finally attains enlightenment. But if this vajra-like antidote is yet another defiled phenomenon, then what could refute it? If it is a defilement, then it also needs an antidote. But if the Buddha has no jñanas and kayas of his own, he would be unable to refute it. So some of our opponents say, well it just exhausts. But that explanation doesn’t really work either, because then our supposedly toughest defilement becomes the easiest to remove, as you can just sit and wait until it exhausts itself. So there is a big debate about how does the vajra-like antidote function. And this debate isn’t really resolved in the Madhyamakavatara. If you want to learn more, please refer to other texts such as the Uttaratantra.

Verse 11:13

The Buddha knows everything, even though there is nothing to know [t = 0:45:28] [MAV PDF page 373]

When we talk about the Buddha, the commentator Gorampa says, yes, we have proved that he doesn’t have dualistic mind – we have proved he’s nondual – but that doesn’t mean he is a vegetable. Beyond the fact that he has no dualism, we do not know anything else. Remember the Heart Sutra: “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form”, so we also know that emptiness is all the aggregates, including consciousness. We know emptiness is not nothing. But what it is, we don’t know. So in verse 11:13:

[11:13] If the uncreated is suchness, [perceiving] mind too is uncreated

Therefore, realization of suchness is realizing that nature.

As a mind that fully perceives an object

Knows it in conventional dependence.

So when we say ‘Buddha knows everything’ or ‘the Buddha is omniscient’, these statements are only conventionally true, because all these objects of knowledge are unborn and the self is unborn. And on page 374 we remind ourselves that with any kind of representational theory of knowledge, which includes all the Buddhist schools from the Sautrantika onwards, we don’t say that we perceive an object like a blue object directly. We only perceive its reconstruction, its representation. It’s a virtual reality, not something truly existing. And similarly, we can say the Buddha knows everything, even though there is nothing to know.

Verse 11:14

The kaya similar to the cause [t = 0:46:11] [MAV PDF page 374]

Verse 11:14 introduces the ‘kaya similar to the cause’, gyutun gyi ku (Wylie: rgyu mthun gyi sku, Tibetan: རྒྱུ་མཐུན་གྱི་སྐུ་), which we’ll talk about a fair amount over the coming verses. This kaya is not part of the nirmanakaya, but it’s rather the manifestations that arise as the reflection of the infinite merit of the sambhogakaya Buddhas.

[11:14] Sambhogakaya is attained through [the Buddha’s] merit,

And through emanations in the sky and other [locations]

He teaches the Dharma of suchness,

So even the world perceives suchness.

This can manifest all kinds of phenomena – teachers, teachings, trees, water, bridges, sound, all kinds of ordinary phenomena, and some would even say treasure teachings. And the reason we introduce this is to answer the question: if the Buddha has no conception, how does he teach? How does he benefit beings? Because we know that already on the 7th bhumi the Buddha has abandoned conceptions. He has abandoned the notions of subject, object, and action.

Verse 11:15-11:16

If the Buddha has no conceptions, how does he benefit beings? [t = 0:46:45] [MAV PDF page 375]

The analogy here is given of a potter, who spins his potter’s wheel, and (as you may know if you’ve worked with a potter’s wheel) you spin it so it has a lot of momentum, and then you don’t have to keep spinning it. You can use the momentum of the wheel to work and make a pot, without needing to continue spinning the wheel. So similarly, while the Buddha was on the bhumis, he was collecting merit and making aspirations, and that created the so-called ‘momentum’ which continues into Buddhahood. And so we say in the last two lines of verse 11:16 that Buddha-activity is caused by the merit of sentient beings, but the condition is the aspiration of the Buddha while he’s on the path.

[11:15] Just as when a strong potter

Spins his wheel for a long time to set it turning,

Later with no exertion of effort,

The turning is seen to cause a pot.

[11:16] Likewise, without any effort at present

[The Buddha] resides as the embodied Lord of Dharma,

Through the virtues of ordinary beings, and his own extraordinary prayers,

His greatness being inconceivable.

Here the idea is that the Buddha has internalized something, and now it operates through its own momentum. We’ll see this again next week when we talk about spontaneous action. This is the idea of action without dualistic intention, and even in the conventional world, we can see versions of this with any kind of mastery. So for example, a tennis player can respond to a serve which leaves the racquet at 130 miles an hour. Now, if you actually time it, you have significantly less than 500 milliseconds to respond, to return the serve. And this requires years of training – of the optometric system, the perceptual system, the cognitive reactions – until the return of serve is completely unconscious, completely non-conceptual. I think this is actually a good example of how if we practice, we can internalize our practice to a state where it no longer needs to be accessed conceptually, in the same way that a tennis player doesn’t need to resort to conceptual thinking in order to return to a serve.

There is a doubt here. What is the origin of the merit of sentient beings? Because this merit supposedly comes from the Buddha’s blessings in the first place, and so we seem to have a circular reasoning problem, where merit is both received from the Buddha’s blessings and also the source of Buddha’s blessings. Rinpoche said, “these two verses have always bugged me; I’ve asked many khenpos and never got a satisfactory answer”. He didn’t go into what, exactly, bugs him but perhaps we can bear this in mind, and maybe ask him next time we see him.

Verse 11:17

The dharmakaya [t = 0:49:37] [MAV PDF page 377]

The next set of verses describes the three kayas. Verse 17 describes the dharmakaya. It’s a very popular verse. All extremes are like the firewood burned by wisdom, by the vajra-like antidote. When the unborn is realized, that is peace; that is freedom from extremes. That is dharmakaya.

[11:17] When the dry firewood of everything knowable,

Is [consumed by the fire of wisdom], the peace of the victorious one’s dharmakaya [is all there remains]

At that moment, there is no creation and no cessation;

When mind ceases, its [enjoyment]-body manifests in actuality.

We say that mind has stopped. Conceptual thinking has stopped, but the nature of mind, which is clarity and knowing, continues. Rinpoche reminded us that once again – like everything in this chapter – this verse is beyond us, because we have no idea what it is to have a mind with clarity and knowing, but without dualism. We are so stuck, not only in our tsendzin, but we’re still stuck within dendzin, the clinging to true existence. So again I’d like reiterate: almost every verse is telling us that this is beyond our rational conceptual minds. So don’t try to grasp or interpret these nondual practices or the Three Kayas intellectually. You can’t. They are beyond concepts. So anything that you’re talking about, explaining to yourself, theorizing about – that is not it. I say this because I can see already there’s a tendency for some of us to want to try and verbalize and conceptualize these nondual practices. That just isn’t going to work. And as we said, in the Vajrayana, and especially in the mahasandhi – when it comes to these examples of nonduality, and especially if we introduce the nonduality directly – that view cannot be introduced with words or language or concepts.

Verse 11:18

The sambhogakaya [t = 0:51:22] [MAV PDF page 378]

[11:18] Motionless, yet this [enjoyment]-body illuminates as the wish-granting tree;

Non-conceptual as the wish-fulfilling jewel;

Permanent, furnishing comforts until [all] beings are liberated,

It manifests within simplicity.

Here the Buddha appears like a wish-fulfilling jewel. So this kaya similar to the cause appears to the 10th bhumi bodhisattva – although not to any of the lower bodhisattvas – and then, in turn, the 10th bhumi bodhisattva can teach the 9th, and all the way on down.

Verses 11:19-11:27

The kaya that is similar to the cause – manifesting as an illusory display [t = 0:51:41] [MAV PDF pages 379-381]

Verses 19-27 describe how the Buddha appears as a display. They’re pretty straightforward. And as you read through the verses, you will see that he can display everything – his conduct in samsara, the bodhisattva bodies and activities, Buddha realms, disciples, retinues, teachings. All sentient beings from the first moment they became bodhisattvas, even ordinary beings. All of the three worlds, basically.

[11:19] Accordingly, the Muni Lord may in an instant

And in a single body manifest his previous births,

Although already ceased, and without effort,

He may display every possible detail.

[11:20] The buddhafields; the buddha;

His actions and powers;

The number of shravaka sangha and their nature;

The bodhisattvas and their forms;

[11:21] Which Dharma, how he himself was,

Which conduct he practised [as a result of] hearing the teaching;

Which offerings he made and how much were offered –

Without omissions, he can display all these.

[11:22] Likewise, his [practice of] discipline, patience, diligence, samadhi

And wisdom, as he practised them

Flawlessly – all these actions,

He also displays within every pore of his body.

[11:23] Also [he can display how] the buddhas of the past, those to come,

And those of the present will as long as the sky lasts,

With a penetrating voice show the truth so the afflicted

Beings may be liberated, and [how they themselves] remain in this world,

[11:24] And from the first developing of bodhicitta until enlightenment,

How all their actions have a magical display’s nature.

Knowing this and that we are likewise, in their pores

They will display all this clearly in a single instant.

[11:25] Likewise the actions of the three times’ bodhisattvas,

The pratyekabuddhas and all noble shravakas.

Beside those of ordinary individuals,

He can display simultaneously in every pore.

[11:26] This Pure One, according to his will,

May display a single mote of dust as the entire universe,

And the infinite universe as a mote of dust,

Without the dust mote becoming any bigger or the universe any smaller.

[11:27] Without thoughts, until the end of [cyclic] existence,

You can display as many actions as there are instants,

As infinite as there are worlds,

And dust motes within in these worlds.

Let’s take just one example: verse 11:26. He can put all the universes that exist within a single atom, and he can make one atom as large as all the universes. Yet the atom will not become bigger, and the universes will not become smaller. These things are beyond us.

Enlightenment is not the same as nirvana [t = 0:52:33] [MAV PDF page 383]

On page 383 there’s an additional discussion on Buddha qualities, making the point that the Mahayana understanding of nirvana is quite different from the Shravakayana understanding. In the Shravakayana, nirvana is seen as something like the extinction of fire or the evaporation of water. These are good analogies for how the extreme of true existence is stopped. For the shravakas, since they’re only eliminating the extreme of true existence, then it makes sense that their analogy is that the experience of nirvana is like the extinction of fire or the drying up of water. Nirvana literally means ‘blowing out’ or ‘quenching’, and it usually refers to the three fires or the three poisons of passion, aggression and ignorance. And when they’re extinguished, we’re released from the cycle of rebirth. And actually there’s a distinction made in the Shravakayana between extinguishing the fires during life, and the final blowing-out at the moment of death – these are called nirvana with and without residue. What happens after one reaches nirvana, and after death, is unanswerable. That’s one of the ten questions Buddha didn’t answer.

But for us in the Mahayana, we go beyond all four extremes. ‘Form is emptiness, emptiness is form’. So we don’t end up with just this one extreme like the extinction of fire. So our idea of enlightenment in the Mahayana is very different from the Shravakayana idea of nirvana. It is important to remember that the Shravakayana and the Mahayana have very different views.

Make your mind abundant and open [t = 0:54:18] [MAV PDF page 385]

Rinpoche then said a few words on openness. We’ll talk more about openness later, and we talked about it last week as well – this quality on the 8th bhumi of being able to have fearlessness and confidence to imagine the unimaginable, to have a truly open mind. Openness is about going beyond rational thinking. We realize that although we use words like ‘dependent arising’ and ‘emptiness’ and ‘unborn’, this is purely for the sake of communication, because we lack better words. And as Rinpoche says, even when we use the word ’emptiness’ or ‘shunyata’, we should remember that although it may perhaps be the best single word we could come up with to describe the so-called ‘truth’, it’s really important not to limit or deprive our minds. Don’t fall into thinking of it as a mere absence; certainly don’t fall into thinking of it in a Shravakayana way as just the absence of true existence. It’s really important to remember the abundance and openness of nonduality, of ’emptiness is form’. For example, in verse 11:26 which we just talked about, we have the whole universe fitting into one atom, and Buddha making this one atom as big as the entire universe. Here Chandrakirti is introducing this concept of ronyam (Wylie: ro mnyam, Tibetan: རོ་མཉམ་) or ‘equal taste’. He’s basically saying that as long as we have rational thinking, we will never understand the Buddha. So again, this is yet another reminder for those of us who love to study that if we stay in the realm of logic or reason, we’re never going to understand the Buddha. So don’t get caught up in trying to intellectualize.

Verses 11:28-11:40

The Ten Powers [t = 0:55:55] [MAV PDF pages 385-390]

Next we come to the Ten Powers. They are summarized in verses 11:28 to 11:30, and the subsequent verses go through them in more detail. And again, they are infinite and beyond our rational understanding. So please remember inconceivability and the story of Nightfall.

[11:28] The power of knowing what is and what is not origin; (1)

Likewise knowing the maturation of actions; (2)

Comprehension of various aspirations; (3)

The power of realizing various propensities; (4)

[11:29] Likewise supreme and non-supreme faculties; (5)

The [paths of] knowledge and ordinariness; (6)

Concentrations, liberation, samadhis,

Absorptions – such mental powers; (7)

[11:30] Knowledge of remembering the past; (8)

Knowledge of passing and birth; (9)

Knowledge of exhausting defilements; (10)

Such are the ten powers.

One of them I find quite interesting is the second power, the understanding of karma, which is described in verse 11:32. This power includes the understanding of every aspect of karma and all of its results – all the details of cause and effect down to the most microscopic level.

[11:31] A cause that has created a certain thing,

The Knowing One has taught as the thing’s basis,

Likewise, there are infinite objects that are not its basis.

This knowledge removes obstructions and is [the first] power.

[11:32] Wanted and unwanted [karma], the opposite— the reality of exhaustion,

And the myriad of karmic ripening,

The capacity of unobstructedly knowing each of these objects,

Throughout the three times is [the second] power.

We have previously talked about how dependent arising is literally infinite. When we think about how we explain the things happen in everyday life, we know there is no ultimate set of causes. There is no final explanation. For every set of reasons or causes that we can think of, there are more causes that cause those causes. So it’s literally impossible for us to describe what’s going on. There can be no end to our description or explanation. In thinking about this, I find it helpful to remember the difference between ➜the map and the territory:

• Territory: The territory is the reality of what’s going on. The reality of the entire interlinked network of causes and effects.

• Map: Our narratives, our explanations, our rationality – these make up our map. And no map is ever going to be the territory.

We all know that the map is not the territory. And verse 11:32 is interesting because we’re saying that this is not the case for the Buddha. For him, his map is the territory. For him, it is totality. There is no reduced description. And that makes sense because as we have said, emptiness, dependent arising, Buddha nature, and the Three Kayas – all of these words are referring to the same thing – the nondual nature.

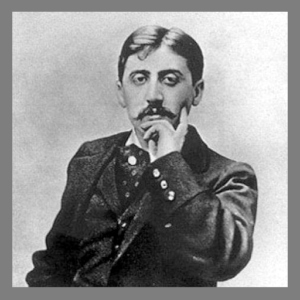

This reminds me of a lovely short story by Jorge Luis Borges from 1946, called “On Exactitude in Science …”, which is about the relationship between the map and the territory:

On Exactitude in Science . . .

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

Suarez Miranda, Viajes de varones prudentes, Libro IV, Cap. XLV, Lerida, 1658

I love this story. It’s such a wonderful reminder of nonduality – learning to let go of this futile attempt to reduce everything to these limited descriptions, which is all that our minds can handle. Our limited rationality, our limited narratives, are just like these futile attempts to build a complete map of the empire.

I’m not going to go through the other Ten Powers. You can read them. The verses are poetic, inspirational, and I would say completely beyond us.

[11:33] The intentions arisen from the strength of desire and so forth;

The vast multitude of lower, middling and supreme aspirations;

And other hidden aspirations – this knowledge

Covers every being of the three times, is [the third] power.

[11:34] The buddhas, knowledgeable about the divisions of constituents,

Called the nature of the eyes and so forth constituents.

The infinite knowledge of the perfect buddhas,

Penetrates all aspects of phenomena. This is [the fourth] power.

[11:35] Discursive thought and so forth may be supreme for the very sharp,

Yet not so for the middling and inferior, it was taught.

Comprehending how the eyes and so forth are established in mutuality,

Such is [the fifth] power of the desirelessness of omniscience.

[11:36] The paths of buddhas, of pratyekabuddhas,

Of shravakas and of bodhisattvas; [the paths of] pretas,

Animals, gods, humans and the denizens of hell –

Unlimited and unobstructed knowledge of these is [the sixth] power.

[11:37] The world’s various yogin’s different meditations

And eight liberations of shamatha,

And the single and eightfold absorptions –

Unobstructed knowledge of these is [the seventh] power.

[11:38] When he himself was deluded and dwelling in samsara,

The cyclic existence of other sentient beings,

As infinite many as they are, their origins and countries,

Such knowledge and capacity is [the eighth] power.

[11:39] The transmigration of every sentient being,

Their lives and their worlds, to the very limits of space –

Knowing the details and perceiving the time

Such unobstructed perfectly pure, infinite [knowledge] is [the ninth] power.

[11:40] Through the power of omniscience, swiftly the buddha’s

Kleshas are purified, destroyed together with their habitual patterns, and,

The afflictions of the disciples cease through intelligence,

Such infinite unobstructed knowledge, [the tenth] power.

Verses 11:41-11:43

The Buddha’s qualities are indescribable [t = 0:59:31] [MAV PDF pages 390-396]

Verse 11:41 really makes this point. It’s a beautiful verse. It says it’s not because there is no sky that birds turn back, they turn back because their strength exhausts. Likewise together with their disciples even the bodhisattvas must relinquish describing the sky-like qualities of the Buddhas. This is just like the map. We cannot describe the whole territory. It’s too vast. We’re just going to get exhausted like the birds, and that does not mean we’ve reached the limit of the sky. Yet again, reiterating, this nonduality is beyond our rational understanding.

[11:41] It is not because there is no sky that birds turn back –

They turn back as their strength exhausts.

Likewise, together with their disciples, even the bodhisattvas,

Must relinquish describing the sky-like qualities of the buddhas.

[11:42] Therefore, how can someone like me know of your qualities?

Or be able to describe them?

Yet, as noble Nagarjuna has explained these,

I have set aside hesitation to speak briefly on these.

[11:43] The profound being emptiness,

The vast are the other qualities.

Through knowing the ways of the profound and vast,

These qualities will be accomplished.

There was a discussion on page 394 about when we talk about the qualities of the Buddhas, the rangtong and the shentong traditions have different views, even though they are all followers of the Madhyamaka. Because for the shentongpas in particular, when they talk about ultimate reality, or yongdrup (Wylie: yongs grub, Tibetan: ཡོངས་གྲུབ་), they embellish it with words like “permanent”, “primordially accomplished”, and things like that. And obviously the rangtong school would not agree with words like this, because they would say that words like “permanent” imply true existence. And the shentongpas would also say that even the qualities of the Buddha, like the 32 Major Marks, things like his copper-coloured fingernails, even these cannot be produced; they have always been there. That probably doesn’t make much sense to us right now, and indeed it’s not explained in the Madhymakavatara. But if you go on to study the Uttaratantra, you will see that these words like “permanent” and “self” are actually being used to refer to the nondual. So when shentongpas use the word “permanent”, it’s being used to mean ‘beyond permanent and impermanent’, both of which are dualistic. We don’t have a word for ‘beyond permanent and impermanent’ in English, and so through lack of words, we end up using the word “permanent”. We could equally call it something different; it’s just that we don’t have a word for it. But we should not misunderstand how these words are being used.

Just a reminder: all of this is completely beyond our words and concepts. So, much of this really is just praise and inspiration and aspiration. And actually the source here, as we discuss on page 390, intriguingly all of this comes from Nagarjuna’s Collection of Praises. We tend to think of him as the ultimate philosopher, the ultimate rationalist; but he wrote a whole series of other works which are series of praises: Praise to the dharmadhatu, Praise to the beyond-worldly, Praise to the inconceivable, Praise to the ultimate, and so on. These are very poetic, very beyond-rational kinds of teachings. It’s helpful to remember that even when it comes to our hero Nagarjuna, we shouldn’t have too narrow a view. There’s much more to him than we might think.

Dependent arising isn’t the same as emptiness [t = 1:02:26] [MAV PDF page 395]

On page 395 Rinpoche made an important point that we need to be careful when we talk about dependent arising. Even though we tend to use the word interchangeably with emptiness, they’re not actually the same. For example, in Week 3 we came across Thich Nhat Hanh’s example of how he can see the cloud in the piece of paper, but Rinpoche cautioned us to be very careful when we use these examples not to develop a wrong understanding. He said:

We hear confused talk from small time buddhists like us. They say, as if they really understand dependent arising, “Yes, I can see why buddhists talk about dependent arising. Because we human beings we eat and then we shit and then it goes to the earth, then the tree grows: everything is dependent”. That’s a very sweet way of thinking about dependent arising, but there’s something very big missing here, and that’s the selflessness aspect. As long as you leave out selflessness, there is no dependent arising. That’s very important to remember, so make a big multi-coloured highlight in your notebook.

Verses 11:44-11:47

The nirmanakaya [t = 1:03:32] [MAV PDF pages 396-397]

Now we turn to the nirmanakaya. And in verse 11:45, Chandrakirti emphasizes that the Buddha taught “an undivided single vehicle”. We’ve heard this before in verse 6:79, and actually last week as well with Mipham’s commentary on verse 6:179. Ultimately the Buddha taught only one vehicle. Rinpoche’s comment here is important. We talk a lot about love, compassion meditation, and methods like that, but on their own, they will not contradict ignorance. They cannot defeat it entirely. The only way is selflessness, emptiness. Only these teachings are a complete antidote to ignorance. And so even when His Holiness the Dalai Lama says, “my religion is kindness”, we have to realize that it’s a very provisional teaching. Unfortunately, it has misled so many people in the West who think that because they are cultivating and practicing kindness through their religion or their approach to psychology or self-help or whatever they’re doing, they think it’s the same as Buddhism. Far from it. As Rinpoche said, unless the path has selflessness, unless the path has emptiness, it’s not going to be an antidote to ignorance. The other verses here are quite straightforward.

[11:44] After achieving the immutable kaya, you returned once again to the three worlds with emanations,

Descending, taking birth and showing the Dharma of attaining peaceful enlightenment.

Thus for all those subscribing to the deceits of the world,

Who are bound by those chains, through your compassion, you lead these beyond suffering.

[11:45] Therefore, apart from knowing suchness, for removing the various stains

There is no other method, as phenomena know no divisions of suchness.

The mind that perceives suchness is also not divided.

Therefore, you taught sentient beings an undivided single vehicle.

[11:46] Because sentient beings have the impurities that make them err,

They do not perceive the profound scope of the buddhas.

Tathagata, because you possess wisdom together with the means of compassion,

You vowed: “I shall liberate sentient beings.”

[11:47] Just as a wise [captain] will [miraculously] manifest a beautiful city,

To relieve his crew when voyaging to an island of jewels,

Likewise, you connected your [shravaka and pratyekabuddha] disciples with the [lower] vehicles to give them peace,

[While] you spoke otherwise to those with trained minds, free [from emotions].

Verse 11:48

We cannot talk of the time of Buddha’s enlightenment [t = 1:04:40] [MAV PDF page 397]

Verse 11:48 is another inconceivable verse. When we talk about the time the Buddha became enlightened, we can talk about combining all the dust particles in all the Buddha realms and then counting as many years and life spans as all these endless dust particles in the buddhafields, and it sounds like we’re talking about something a very long time ago. But actually, as Rinpoche said, we are talking about an all-pervasive quality that pervades the Buddhas of the three times – past, present, and future. Similarly, millions upon millions of 10th bhumi bodhisattvas are achieving enlightenment at this very moment. So enlightenment is everywhere, all the time; it’s all-pervasive.

[11:48] Sugatas in the buddhafields of all the directions,

Numerous as the particles and atoms in these –

For as many aeons will you enter holy supreme enlightenment.

Yet, this secret of yours should not be told.

And yes of course conventionally, we say “the Buddha attained enlightenment”, but it’s a very relative way of speaking. Rinpoche gave a lovely example, also taken from the Uttaratantra, of a poor family that inherits a plot of land from some ancient ancestors. The family is very poor; but then one day, they find there is a gold mine on their land. And maybe you could say they have “discovered” this gold mine and have “become” rich, but that’s just a conventional way of describing things, because they’ve always had it.

Verses 11:49-11:51

The Buddha remains forever out of wisdom and compassion [t = 1:06:07] [MAV PDF pages 398-400]

So until now in Chapter 11 we’ve been talking about how the qualities of the Buddha and his enlightenment are completely beyond us. But now Chandrakirti changes direction completely. In verses 11:49-11:51 he says that actually the Buddha remains forever out of his compassion and does not enter the supreme peace of nirvana, because samsara is endless, and there are endless suffering sentient beings, so the goal is never exhausted. And so Chandrakirti closes his entire text by saying that the Buddha has no enlightenment.

[11:49] Victor, as long as the worlds have not attained supreme peace,

As long as the sky has not disintegrated,

You, born from the Mother of Wisdom and nursed by her loving kindness,

How could you enter supreme peace?

[11:50] As they ignorantly eat the poisonous food of ordinary experience,

Your care for your family of ordinary individuals,

[Is greater than] the sufferings of the mother of a poisoned child,

Thus you, protector, will not enter supreme peace.

[11:51] Because they are ignorant, fixating on [things as] real or unreal,

Because they suffer from birth and death, from not achieving the wanted, and being struck by the unwanted,

Because of the destination of the evil, you are moved by tenderness for the world,

Bhagawan, through compassion you have shunned peace and not chosen nirvana.