Alex Li Trisoglio

Aspiration: Week 9 – Continuity

Introduction to Week 9

Welcome

Hello and welcome to Week 9 of the review of Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s teachings on Samantabhadra’s King of Aspiration Prayers, the Pranidhana-Raja. This week’s title is “Continuity”, and our subject this week is how to take our practice into our everyday life as a continuing journey of personal growth and spiritual transformation. This week’s image is of a person passing a candle to another person, illustrating the idea of passing on the light of wisdom and compassion.

As usual, before we start, let’s reflect on our aspiration and motivation. And in the spirit of using our everyday life as the path, I’ll read a few verses from chapter 3 of Shantideva’s Way of the Bodhisattva (the Bodhicharyavatara):

[18] May I be a guard for those who are protectorless,

A guide for those who journey on the road.

For those who wish to cross the water,

May I be a boat, a raft, a bridge.

[19] May I be an isle for those who yearn for land,

A lamp for those who long for light;

For all who need a resting place, a bed;

For those who need a servant, may I be their slave.

[20] May I be the wishing jewel, the vase of wealth,

A word of power and the supreme healing,

May I be the tree of miracles,

For every being the abundant cow.

[21] Just like the earth and space itself

And all the other mighty elements,

For boundless multitudes of beings

May I always be the ground of life, the source of varied sustenance.

[22] Thus for everything that lives,

As far as are the limits of the sky,

May I be constantly their source of livelihood

Until they pass beyond all sorrow.

Let’s take a moment to tune our motivation.

[Pause]

Purpose and aspiration

So as we come to the end of this program, I’d like to revisit a couple of questions we asked at the beginning in Week 1:

- Firstly, what is our aspiration? Even if we don’t have the time to do a lot of formal retreat or formal sadhana practice, Rinpoche has often said that “Aspiration is one thing that is easy to do and that we can do at any moment.” It’s very user-friendly and very economical. There really are no excuses not to be able to practice aspiration. So what does our own practice of aspiration look like?

- Secondly, what does it mean to live a good life and be a good person? And whether or not we consider ourselves Buddhist, we all have aspirations in our life. We all want to live a good life, however we define that. So what does it mean to us to live a good life? What does it mean to be a good person? What are we aspiring for in terms of our life purpose?

Now that we have gone through the verses of the Pranidhana-Raja, I hope you’ve had the opportunity to think a little more about these questions, and that your answers today will in some small way be informed by the grand view and vast aspiration of Samantabhadra.

In Week 1, we also talked about the idea that we can be intentional about our aspirations, and that we can think of aspiration as something we can craft, not simply something that’s a “given” for us. So I also invited us to consider the question, how many of us have really thought what it is that we want from our lives? We all have hopes, goals and aspirations, but to what extent are they actually ones we’ve chosen for ourselves, rather than just conventional ones that perhaps our parents want for us or that society expects from us?

And now that we’re considering how to take our practice of aspiration into our everyday life, this question of designing a way of life that is aligned with our aspiration becomes particularly important. The Buddha taught on the importance of right livelihood as one of the eight practices in the Noble Eightfold Path, so it’s worthwhile to consider how we have set up the conditions of our outer life in the world — including our choice of work and companions — and how this supports our practice.

If you’ve made it as far as Week 9, you’re perhaps already somewhat persuaded by the idea that aspiration is important, and hopefully you feel a certain inspiration or curiosity when it comes to the vast and profound Mahayana aspiration set out in the Pranidhana Raja. And we cannot say that we don’t have opportunities to incorporate the aspiration of the Pranidhana-Raja into our practice. During the past eight weeks we’ve seen how aspiration can be integrated into everything from the simplest offering of a flower, to the richness of the Seven-Branch Offering, to the vast and inconceivable visualisation of infinite Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, right up to the highest non-dual practices of Mahamudra and Dzogchen.

We’ve seen that as our practice and realisation of emptiness deepens, aspiration ceases to be a discrete practice, and instead becomes an integral, seamless quality of an enlightened relationship to reality. It is no longer about doing something specific, but about being in a continuous state of inseparable aspiration and dedication, where every moment is an expression of the ultimate union of wisdom and compassion, beyond the confines of conventional time.

We’ve also explored how aspiration is crucially important for Bodhisattvas at each stage of their journey, from the initial Stage of Aspiring Conduct, to the final moments of the highest paths and bhumis before attaining enlightenment. And even after their enlightenment, the Buddhas continue their limitless activity of benefiting sentient beings because of the inconceivable aspirations they made during the path. So hopefully we now have a much richer understanding of what it means to aspire following the example of Samantabhadra, and why this is such an important foundation for the Bodhisattva path.

We’ve talked about how to integrate aspiration into our practice. Our question this week is how can we integrate the practice of aspiration into our lives? One of the practical challenges that many of us face is that we are just so busy with the demands of our work and family lives. There’s just so much to do, and even the basics of attempting to secure a right livelihood for ourselves in the modern world can sometimes leave us feeling that we’re just treading water. So I’d like to turn to a teaching that Rinpoche gave in Taipei in April 2023 called “Lying Flat Buddha”, where he considers how we might approach the challenges of our increasingly demanding lives.

Surviving the rat race – or lying flat?

Tang ping (躺平), bai lan (摆烂) and fo xi (佛系)

Rinpoche was inspired to name his teaching “Lying Flat Buddha” because of the growing popularity of the Chinese idea of tang ping (躺平). This is a Chinese neologism or slang term which literally means “lying flat” and describes a personal rejection of societal pressures to overwork and overachieve, such as in the “996″ working hour system. “996” describes a 72-hour work week — in other words 9am to 9pm, six days a week — that has been adopted as the official work schedule by many Chinese IT and internet companies. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many young people find it very difficult to achieve any kind of work-life balance in the 996 system, and some are choosing to “lie flat” in an attempt to redress the imbalance. They’re lowering their professional commitment and economic ambitions and simplifying their goals, while still doing enough to meet their own essential needs. Put simply, they’re choosing to prioritise psychological health over economic materialism. They’re choosing life over work. It has been suggested that tang ping is perhaps the closest thing in contemporary Chinese society to the hippie movement of the 60s and 70s in the West, which was likewise inspired by a desire to go against the values of mainstream culture.

A newer related term is bai (摆), short for bai lan (摆烂), which means “let it rot”. This is another Chinese slang term that also corresponds to the English phrase “quiet quitting”. It means actively embracing a deteriorating situation, rather than trying to turn it around. Basically, it refers to a voluntary retreat from pursuing certain goals once you realise they’re simply too difficult to achieve. The concept originally described a phenomenon observed in the NBA basketball league, where if a team is having a bad season, they might start intentionally throwing games away in order to get a more favourable draft for the next season. On Chinese social media, young people are turning to bai lan as the expression of despondency in the face of decreasing social mobility and economic uncertainty. By doing so, they’re rejecting China’s fiercely competitive culture and embracing mediocrity and ordinariness instead.

Another related term is fo xi (佛系), which means “Buddha-like mindset”. Again, this is Chinese slang that means lacking ambition and desire for money and success, and instead being satisfied with a simple life. As with tang ping and bai lan, it is used to describe a rejection of the rat race of contemporary workaholic Chinese society for a tranquil and seemingly apathetic life.

As Rinpoche pointed out, the ideas behind these words can also have a positive meaning. For example, prioritising inner goals and rejecting the rat race, and not getting lost in a life of fierce competition for its own sake. The idea of a simple life with less stress and struggle is no less attractive to young people in the West.

But all these terms have a negative aspect as well. Lying flat, quiet quitting and giving up have the connotation of adopting a loser’s attitude, being unable to face difficult situations, and always finding an excuse to not take responsibility. Dropping out means no longer proactively driving positive change in society or trying to make things better. So it is perhaps unsurprising that hard-working and ambitious parents might not always respond positively when they see their children adopting these attitudes. And indeed, some Chinese parents use the term fo xi to chide their children for being lazy and not working hard enough, calling them “Buddhist boy” or “Buddhist girl” to criticise their lack of desire and ambition.

Tang ping and Buddhism

So as Rinpoche noted, this puts Buddhism in an interesting position. Are Buddhist values seen as good or bad? When people associate Buddhism with laziness, dropping out, giving up and lying flat, even if this is only a joke, it may be worth talking about. Because it’s true that Buddhists talk about concepts like renunciation and being in the moment. Right from the beginning of our path we are taught to aspire to go beyond the eight worldly concerns or eight worldly dharmas. These are the four pairs of opposites — gain and loss, fame and disgrace, praise and blame, pleasure and pain — that are the typical sources of attachment and diversion that keep us bound in our ordinary existence of samsara and distract us from enlightenment. So we aspire to go beyond these dualistic distinctions and values that are currently driving us. And it would be easy to misinterpret this teaching to mean giving up and dropping out of worldly life.

And Buddhism also admires the Taoist concept of wu-wei, which can be translated as non-action or effortless action. This means going with the flow, taking a laissez-faire attitude, and letting nature take its course. And it’s particularly celebrated as the spontaneous action of the Mahasiddhas and yogis in the Mahamudra and Dzogchen traditions. But again, it’s easy to misinterpret non-action to mean giving up and doing nothing.

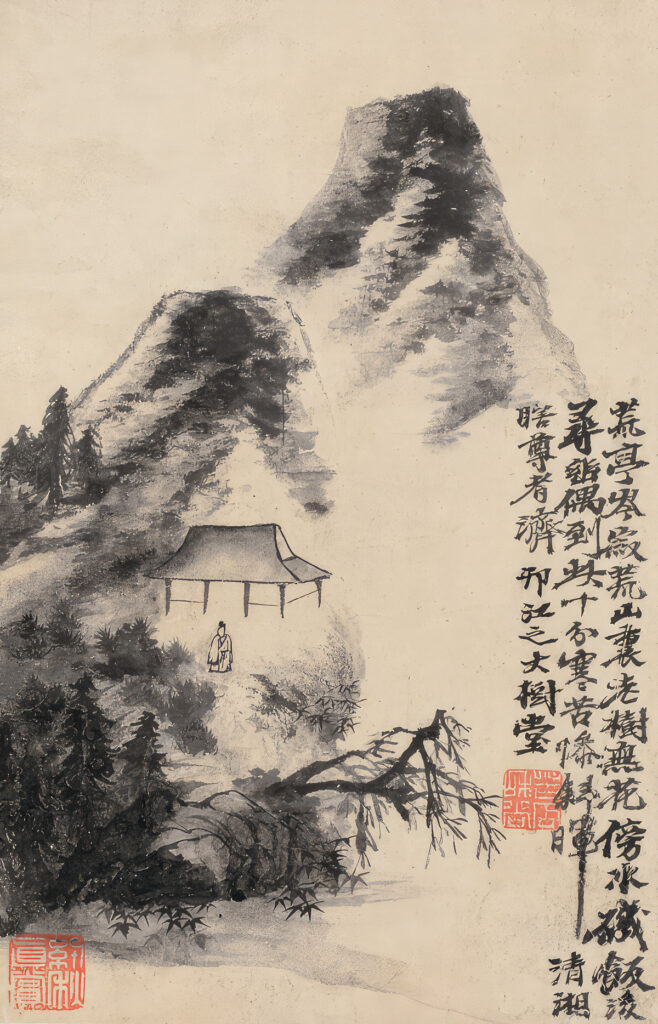

And of course, Buddhist art and culture celebrates living simply, especially the Buddhist arts and culture of China and Japan. Even today, it doesn’t matter whether you’re in Hong Kong or Singapore or Taipei, even in the busiest downtown apartment building, most probably you’ll see a painting of a mountain on one of the walls. And on the mountain there’s a small hut with a single person looking down towards the valley. And so as Rinpoche said, it seems the Chinese have a kind of romantic and sentimental value for a secluded, simple life, even if that’s far from the reality for most people in the contemporary world. So it’s not surprising that we might resort to lying flat as a way to recreate that kind of simplicity, peace and tranquility in our lives.

But there’s a big difference. Buddhism isn’t about giving up. Rather, it’s about transcending the whole samsaric game completely. As Bodhisattvas, we do not reject the world or other sentient beings. We’re completely engaged in the world and committed to benefiting and liberating other sentient beings. We might be kings or prostitutes or great merchants or gangsters, but although we’re in the world, we are not of the world. We’re no longer trapped in the world.

And so as Rinpoche says, if we’re able to understand words like tang ping and fo xi and wu-wei in the way that they were understood by the great masters of the past, in traditions like Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism and Hinduism, then probably tang ping should be in our school textbooks. More than ever, we need to aspire for a tang ping life. But this is not easy. Lying flat is an art. It’s not that easy to achieve. And lying flat is not only an art, it’s also a craft. In order to lie flat, we need merit. We need to be quite lucky. We need to be savvy. We need to be strategic. And just as it’s taught in the ancient texts, in order to do nothing, we actually have to do a lot of things. We need some sort of wisdom to really manage to do that. And of course, all of this is founded on Bodhichitta and the aspiration to live following the example of the great Bodhisattvas.

There are many obstacles

To lie flat and practice tang ping in the authentic way of the Bodhisattvas, there are lots of obstacles, the greatest of which is our own values and mindsets. We fear being left out and left behind. We fear missing out on things, not having enough, not achieving enough. We’re very self-conscious about our social status and our position in the social hierarchy. We don’t want to be seen as losers. It’s unattractive. And more than ever, we’ve been educated and brought up to focus selfishly on our own success and the success of our family.

As Rinpoche said, for those of us that have children, of course we want the best for them. We want them to have a good education, a good career, and a happy and fulfilling personal and professional life. If we have the means, many of us will be proud to support our children going to Harvard or Yale or Oxford. It’s our responsibility as parents to guide our children and lead them in a good direction.

But this is difficult, especially when even the world of education has become so competitive. It seems that expectations around grades and extracurricular activities are always rising. So if my neighbour’s daughter is taking extra piano lessons, I’m probably going to feel the pressure to get my own child to have extra cello lessons or something. Who wants to be responsible for not giving their children every opportunity? The world is uncertain already, and in a future of economic insecurity and artificial intelligence and climate change, it’s not unreasonable that we should want to ensure we’ve done all that we can to set ourselves and our children up for success. Or at least to mitigate as many of the downside risks as we can afford to. And when we’re realistic about the challenges of today’s world, it can be hard to have a tang ping attitude.

And for young people in particular, it seems there’s growing pessimism about the future. As Rinpoche said, until recently, young people tended to put their hope and faith in ecology and a healthy environment, but now even that seems to be in decline, and for good reason. So there is a growing sense of anomie and purposelessness. Many centuries ago, the purpose of life, or the definition of a good life, was determined by religion. With the Enlightenment and the rise of secularism, the ideals of the good life and the good society were set out by social and political philosophers, who highlighted the importance of freedom and democracy. But it seems that with the rise of political dysfunction, autocracy and polarisation, many young people are also losing faith in democracy. And if environmental destruction and political dysfunction continue to worsen, which seems quite possible at least in the short and medium term then, as Rinpoche said, there’s a real danger that we’ll lose our sanity. So on both the individual level and the societal level, maybe it’s worth revisiting some of the ancient wisdom in the Buddhist teachings.

Because it’s unclear that our educational and economic systems are going to provide answers, or ways to free ourselves from the hopelessness and meaninglessness of the rat race. As Rinpoche said, it’s almost as if the modern education system and economy looks at you as an espresso machine. You’re educated, assembled and programmed to work efficiently, to produce, to be a slave to the system. And you’re expected to slave until your last drop of energy. It’s almost as if the whole system has been designed to keep us focused on just making ends meet. It’s incredible that we have to take leave for a week to go away somewhere just so we can watch the sunset. It’s just so sad. So yes, we could be forgiven for temporarily dropping out and lying flat. That can happen. But most of the time it’s just a reaction. At the end of the day, a human life should be more than about becoming an efficient tool or machine for making things.

So we need a different way of thinking about the purpose of our life. We need a different model of the good life that we can aspire to. And yes, we should aspire for enlightenment and the ability to realise the truth. But at the very least, we need to develop some sort of basic sanity. And for this, the Buddha taught the Noble Eightfold Path.

All lives are good lives for a bodhisattva

How can we make Buddhism work in the context of our life?

So let’s assume that we’ve bought into the possibility that the wisdom of Buddhism might provide a positive alternative to tang ping and fo xi, to lying flat and dropping out. We still need to find a way of making Buddhism work within the constraints of our work and our life. But perhaps this isn’t as much of a problem as we might imagine. In fact, there may not be a problem here at all.

As we’ve seen in the verses of the Pranidhana-Raja, the nature of our work or life situation need not be an obstacle to practicing the path. Just like the lotus born in the mud, if it will benefit sentient beings, I aspire to be born as a king, a prostitute or even a gangster so that I can benefit beings according to their expectations and in whatever specific ways are relevant to their situation.

The YouTube Bodhisattva and the Barista Bodhisattva

We saw this with the YouTube Bodhisattva. Let’s suppose you have a friend who always wants to watch YouTube and you want to benefit your friend. You might think that watching YouTube is not beneficial. But as a Bodhisattva, if you were to straight away step in and scold this person for watching YouTube, then all that’s going to happen is they’re going to stop listening to you. So instead, you must begin by watching YouTube as much as the other person wants in order to inspire them and then slowly lead them away from YouTube. Of course, if you’re not careful, you also will become a YouTube addict. Then, as Rinpoche said, there will be two YouTubers. So we have to aspire that as we work for the benefit of others, we will never become stained, just as the lotus does not get stained by the muddy water. But as long as we bear this in mind, the path of the YouTube Bodhisattva is no less noble than any other Bodhisattva path.

Rinpoche also gave the example of the Barista Bodhisattva. Suppose that an Eighth Bhumi Bodhisattva, out of his incredible power, sees there’s a specific coffee shop somewhere in Casablanca and that at a certain point in time someone is going to visit this coffee shop, but just for half an hour to have a cup of coffee. The Eighth Bhumi Bodhisattva knows that this person will become a perfect vessel for the Dharma only at that time. The Bodhisattva will wait. This is the power of their patience. And then perhaps in January of that year, the Bodhisattva will take a job as a barista in that coffee shop. And then at last the person walks in and orders an espresso and this Barista Bodhisattva exchanges maybe two and a half sentences with them. That’s all. And that’s it. It’s over. The Bodhisattva has done his job. He’s very happy. He has planted the seed of the Dharma.

All lives are a suitable basis for us to benefit sentient beings

So in the same way that the Bodhisattva can manifest as a king, a prostitute, a gangster or even a barista in order to benefit beings, no matter what our current life situation and profession, that is equally a suitable basis for us to benefit sentient beings. All lives are good lives in that sense. And as Rinpoche has said, if a Bodhisattva is required to be an idiot from five o’clock to seven o’clock today, why not? That is included. If a Bodhisattva needs to be helpless or sick in order to benefit beings, they should do that. If a Bodhisattva needs to be homeless or a drug addict or even to be annoying for half an hour, may I be that. Basically, you cannot exclude anything, not a single quality. The only thing that can be excluded is something that goes against the truth. In other words, something that will not benefit others. So going back to Shantideva’s words:

[18] May I be a guard for those who are protectorless,

A guide for those who journey on the road.

For those who wish to cross the water,

May I be a boat, a raft, a bridge.

[19] May I be an isle for those who yearn for land,

A lamp for those who long for light;

For all who need a resting place, a bed;

For those who need a servant, may I be their slave.

Sudhana’s journey in the Gandavyuha Sutra

An incredible diversity of teachers

So returning to our text, the Pranidhana-Raja is the 56th and final chapter in the Gandavyuha Sutra, which is part of the Avatamsaka Sutra or Flower Ornament Sutra. This sutra presents the non-dual view of emptiness in terms of a vast cosmological vision of interconnected existence, and it has been very influential especially in East Asian Buddhism. The Gandavyuha Sutra or Stem Array is centred on Sudhana, a young Bodhisattva who is the son of a wealthy merchant. Basically it tells the story of Sudhana’s travels as a pilgrim and Bodhisattva seeking to understand and realise the truth and it gives an account of his journey in which he encounters 52 gurus or masters, all of whom are Bodhisattvas, and many of them are truly mind-boggling.

I wanted to return to this text not just because it’s the source of the Pranidhana-Raja but also because of the diversity of Sudhana’s teachers, which reminds us that no matter what kind of job or career or way of life we might find ourselves in or we might aspire towards, they are all equally well-suited as vehicles for practising and perfecting the Bodhisattva’s way of life. And likewise, if we know how to look, we can find the wisdom of the Buddha in some of the most unexpected places and embodied by some of the most unexpected people. So the Gandavyuha Sutra inspires us and reminds us to adopt the vast and grand view of the Mahayana.

So Sudhana starts his journey by meeting Mañjushri, and Mañjushri teaches him various things and then Mañjushri says to him, “Okay, I’ve finished for now. There’s another great teacher somewhere distant from here, something like 500 mountains and 500 valleys beyond” — the classic Indian narrative construction — “and you must go and learn from him.” So Sudhana obeys Mañjushri and he goes through all kinds of difficulties and penance in the search for this next master who is the bhikshu Megashri. He finally meets the master and receives instruction from him for many years and then finally this master says, “Okay, I’ve finished. You should now go to another place to meet another master.”

And the Sutra continues in this way. It’s basically a story of Sudhana meeting these 52 masters, each of whom teaches him before sending him to another master. And some of these masters are quite amazing. For example, Chapter 5 tells the story of Sudhana’s meeting with Sagaramegha, who describes how by focusing on the ocean and its qualities over 12 years, he saw a Buddha seated on a giant precious lotus arise from the ocean with countless deities of various kinds paying homage to that Buddha, who gave him a teaching called “All-Seeing Eyes” which was so vast that even one chapter of it was too long to ever be written out.

And each master not only has very specific teachings, but very specific ways of teaching. For example, one of the masters is a prostitute and the only way to receive teachings from this master is by Sudhana becoming her customer. And this story of Sudhana’s encounter with the courtesan Vasumitra is told in Chapter 28. As Rinpoche said, “Didn’t I tell you about the Mahayana? It’s mind-boggling stuff. We cannot approach this sutra with our normal thinking.” Usually we have the idea of a master as someone serene, someone morally perfect, all of that, you know, the whole procedure. But here it’s not like that. The teachers that Sudhana meets are far from typical. A perfume seller, a young girl, non-Buddhists, the Buddha’s mother, his wife, merchants, goddesses of the night. And their teachings and attainments are always incredibly vast or so extraordinary as to be beyond conception. And even more unusually, many of them seem to have never met the Buddha Shakyamuni, but have received teachings from other Buddhas, or even countless Buddhas on a mote of dust. So we have a new appreciation for William Blake’s poetic vision that we came across in Week 1:

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.

Sudhana’s meeting with Indriyeshvara

Rinpoche says one of his own personal favourites is the story of Sudhana’s meeting with Indriyeshvara, which is told in Chapter 15 of the Gandavyuha Sutra. Sudhana is sent on his way by his previous master, Sudarshana. And usually when a master sends Sudhana, they give him a detailed description of who the next master is and how to find him, how to go, which mountain to pass, which valley to cross, all of that. But in this case, Sudarshana simply tells him:

Depart, noble one. In this southern region there is a city called Sumukha in the land called Shramaṇamaṇḍala. There dwells a boy by the name of Indriyeshvara. Go to him and ask him, ‘How does a bodhisattva train in bodhisattva conduct? How does a bodhisattva practice it?’

And of course Sudhana spends many years looking for this master. And finally one day, he finds some kids playing on a sandy beach. And there’s a full description about how Sudhana runs to this special eight-year-old child and falls to the ground and prostrates and holds this boy’s feet. And he says, “I’ve been all over the place looking for you.” You know, the normal conversation ensues. “Who sent you?” And he gave the name of Sudarshana, the previous bodhisattva. Anyway, when it comes the subject of this boy’s teaching, Rinpoche says, “It’s so good”. It’s his favourite. It’s about numbers, like one, two, three, four, five, you know, like that. But what’s so amazing is for us, after about a trillion, we’re finished. But this child has so many, many more numbers, about 14 pages worth. And after about the tenth page, the numbers basically sound like a baby babbling. And then you realise the bodhisattva is making fun of mathematics and rationality. You realise that one and a trillion are just an illusion.

Anyway, finally, the 51st bodhisattva sends Sudhana to his last teacher, Samantabhadra. And this is so beautiful because after all these 2,000 pages of the sutra, we come to the conclusion that the best thing you can do is aspiration. Before we reach this final chapter, there’s been talk of shunyata, paramitas, all that kind of high philosophy. But in the end, everything boils down to aspiration.

We can practice aspiration

And so back to us. No matter what our job or way of life, we can always find a moment to aspire. We can step outside the rat race and lie flat, even if it’s only for an hour. We don’t even necessarily need to get away from it all and take a break or a vacation. Instead we can stop for a moment of Dharma, perhaps to recite an aspiration prayer, or take a trip to the Pure Land of North Vancouver [Ed. see Week 8], or to offer a single candle or flower with genuine bodhichitta.

And when it comes to our practice, we should never make the best into the enemy of the good. Of course, it is wonderful to aspire to have the conditions and aspiration to practice diligently and accumulate great merit. But there are many people who feel an attraction to the Buddhist path and want to be Buddhists without giving up their current lifestyle. Even a butcher might want to be a Buddhist, and that is supported in the sutras. In one sutra a butcher met the Buddha and said he really wanted to take refuge, but he was worried because he was a butcher and he was unable to give up his livelihood, even though it involved killing animals. So he asked the Buddha, “What should I do?” And the Buddha said, “From now on, take the vow not to kill from sunset to sunrise.” Now that doesn’t mean the Buddha was giving him a license to kill, but the Buddha was setting out a path through which the butcher could accumulate a little more merit through engaging in some wholesome thoughts and actions.

And likewise, as Rinpoche says, there may be many people who might feel a genuine connection to Buddhism, but who may still want to be free to smoke and drink, eat meat, sleep around, all of that. And it would be very discouraging if we told them that their lifestyle is incompatible with Buddhism, or that the only way for them to make progress on the path is to commit to a serious program of study and practice, for example to study the Madhyamaka in depth or do a three-year retreat.

And as Rinpoche said, this is not what it means to be a Buddhist in any case. A Buddhist is anyone who follows the Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Noble Path. In other words, anyone who accepts the Three Marks:

- Anicca (impermanence), or as Rinpoche puts it, “Nothing is certain”.

- Dukkha (unsatisfactoriness/suffering), or as Rinpoche puts it, “Nothing is one hundred percent satisfying”.

- Anatta (non-self), or as Rinpoche puts it, “Nothing is how it appears”.

And as we saw last week, Rinpoche told us that all that any of us needs to do to accumulate a vast treasury of merit is to seal our every action with the aspiration and dedication of bodhichitta. In this way, even by offering a single flower while thinking, “May this offering ultimately benefit all sentient beings,” you will accumulate immeasurable merit.

Our vision of Buddhism can be a very inclusive and inspiring one. It can include those who can’t meditate, those who can’t commit themselves to intense practice, and those who can’t be vegetarian. And of course, it can include us, even if we may not always be able to live and practice in the way we would like to, or think that we should. Rinpoche quotes Jigme Lingpa’s Prayer to the Mahakalas and Mahakalis, where Jigme Lingpa says:

Even though these people are laypeople

They venerate you, the Triple Gem.

Even though they cannot practice,

They value cause, condition and effect.

Therefore they are worthy of your protection.

In other words, everything comes down to our view and our aspiration. And as we’ve seen, when we begin to practice in the way of the bodhisattvas and aspire for the enlightenment of all sentient beings, our way of understanding our life’s purpose begins to shift. We have a different way of looking at the world and of thinking about our life. So even if we cannot devote our life 100% to practice right now, our aspiration is clear. And then, as Rinpoche says, we’re starting with a different motivation and a different attitude, a different way of looking at the world. We’re talking about confidence, because what we’re aspiring for is an achievable task. Actually, according to the bodhisattvas, even as you begin this aspiration, you have already succeeded.

So even though it might look like we’re still caught in the rat race, our tang ping and fo xi can become part of our bodhisattva path. We’re no longer seeking to escape from our life, but rather, we learn to see it as the perfect basis for us to practice the bodhisattva path and benefit other beings. So let us aspire that all sentient beings can find a way to authentically lie flat (tang ping) and experience Buddha mind (fo xi), no matter what their job or way of life, and that we can all attain enlightenment together. And as Rinpoche said, let’s not forget that for beginners like us, aspiration is the most risk-free and most user-friendly of all practices. It’s something that we can do and we should do. So with that, let’s read Samantabhadra’s King of Aspiration Prayers in its entirety once more.

Samantabhadra’s King of Aspiration Prayers, the Pranidhana-Raja

1. The Seven Preliminaries for Purifying the Mind

1.1. Prostration

[1] To all the buddhas, the lions of the human race,

In all directions of the universe, through past and present and future:

To every single one of you, I bow in homage;

Devotion fills my body, speech and mind.

[2] Through the power of this prayer, aspiring to Good Action,

All the victorious ones appear, vivid here before my mind

And I multiply my body as many times as atoms in the universe,

Each one bowing in prostration to all the buddhas.

1.2. Offering

[3] In every atom preside as many buddhas as there are atoms,

And around them, all their bodhisattva heirs:

And so I imagine them filling

Completely the entire space of reality.

[4] Saluting them with an endless ocean of praise,

With the sounds of an ocean of different melodies

I sing of the buddhas’ noble qualities,

And praise all those who have gone to perfect bliss.

[5] To every buddha, I make offerings:

Of the loveliest flowers, of beautiful garlands,

Of music and perfumed ointments, the best of parasols,

The brightest lamps and finest incense.

[6] To every buddha, I make offerings:

Exquisite garments and the most fragrant scents,

Powdered incense, heaped as high as Mount Meru,

Arranged in perfect symmetry.

[7] Then the vast and unsurpassable offerings—

Inspired by my devotion to all the buddhas, and

Moved by the power of my faith in Good Actions—

I prostrate and offer to all you victorious ones.

1.3. Confession

[8] Whatever negative acts I have committed,

While driven by desire, hatred and ignorance,

With my body, my speech and also with my mind,

Before you, I confess and purify each and every one.

1.4. Rejoicing

[9] With a heart full of delight, I rejoice at all the merits

Of buddhas and bodhisattvas,

Pratyekabuddhas, those in training and the arhats beyond training,

And every living being, throughout the entire universe.

1.5. Imploring the Buddhas to Turn the Wheel of Dharma

[10] You who are like beacons of light shining through the worlds,

Who passed through the stages of enlightenment, to attain buddhahood, freedom from all attachment,

I exhort you: all of you protectors,

Turn the unsurpassable wheel of Dharma.

1.6. Requesting the Buddhas not to Enter Nirvana

[11] Joining my palms together, I pray

To you who intend to pass into nirvana,

Remain, for aeons as many as the atoms in this world,

And bring well-being and happiness to all living beings.

1.7. Dedication

[12] What little virtue I have gathered through my homage,

Through offering, confession, and rejoicing,

Through exhortation and prayer—all of it

I dedicate to the enlightenment of all beings!

2. The Actual Aspiration

2.1. Aspiration for Purity of Attitude

[13] Let offerings be made to buddhas of the past,

And all who now dwell throughout the ten directions of this universe!

Let all who are yet to come swiftly fulfil their wishes

And attain the stages of enlightenment and buddhahood!

[14] Let as many worlds as there are in all the ten directions

Transform into realms that are vast and utterly pure,

Filled with buddhas who have sat before the mighty bodhi tree,

Around them all their bodhisattva sons and daughters!

[15] Let as many sentient beings as there are in all the ten directions

Live always and forever in happiness and health!

Let all beings meet the Dharma

That befits them best! And so may all they hope for be fulfilled!

2.2. Aspiration Never to Forget Bodhichitta

[16] As I practise the training for enlightenment,

May I recall all my previous births,

And in my successive lives, through death and through rebirth,

May I always renounce the worldly life!

[17] Training in the footsteps of all the victorious buddhas,

May I bring Good Actions to perfection,

And my moral conduct be taintless and pure,

Never lapsing, and always free from fault!

[18] In the language of the gods, nāgas, and yakṣas,

In the language of demons and of humans too,

In however many kinds of speech there may be—

I shall proclaim the Dharma in the language of all!

[19] Taming my mind, and striving in the paramitas,

I will never forget the bodhichitta;

May all my harmful actions and the obscurations they cause

Be completely purified, every single one!

2.3. Aspiration to be Free from Defilements

[20] May I be freed from karma, harmful emotions, and the work of negativity,

And act for all beings in the world,

Just like the lotus flower to which mud and water cannot cling,

Or sun and moon that course unhindered through the sky.

2.4. Aspiration to Lead Beings to Happiness

[21] Throughout the reach and range of the entire universe

I shall pacify completely the suffering of all the lower realms,

I shall lead all beings to happiness,

And work for the ultimate benefit of each and every one!

2.5. Aspiration to Wear the Armour of Dedication

[22] I shall bring enlightened action to perfection,

Serve beings so as to suit their needs,

Teach them to accomplish Good Actions,

And continue this, throughout all the aeons to come!

2.6. Aspiration to Accompany other Bodhisattvas

[23] May I always meet and be accompanied by

Those whose actions accord with mine;

And in body, speech and mind as well,

May our actions and aspirations always be one!

2.7. Aspiration to Have Virtuous Teachers and to Please Them

[24] May I always meet spiritual friends

Who long to be of true help to me,

And who teach me the Good Actions;

Never will I disappoint them!

2.8. Aspiration to See the Buddhas and Serve them in Person

[25] May I always behold the buddhas, here before my eyes,

And around them all their bodhisattva sons and daughters.

Without ever tiring, throughout all the aeons to come,

May the offerings I make them be endless and vast!

2.9. Aspiration to Keep the Dharma Thriving

[26] May I maintain the sacred teachings of the buddhas,

And cause enlightened action to appear;

May I train to perfection in Good Actions,

And practise these in every age to come!

2.10. Aspiration to Acquire Inexhaustible Treasure

[27] As I wander through all states of samsaric existence,

May I gather inexhaustible merit and wisdom,

And so become an inexhaustible treasury of noble qualities—

Of skill and discernment, samadhi and liberation!

2.11. Aspiration to the Different Methods for Entering into the “Good Actions”

a) Seeing the Buddhas and their Pure Realms

[28] In a single atom may I see as many pure realms as atoms in the universe:

And in each realm, buddhas beyond all imagining,

Encircled by all their bodhisattva heirs.

Along with them, may I perform the actions of enlightenment!

[29] And so, in each direction, everywhere,

Even on the tip of a hair, may I see an ocean of buddhas—

All to come in past, present and future—in an ocean of pure realms,

And throughout an ocean of aeons, may I enter into enlightened action in each and every one!

b) Listening to the Speech of the Buddhas

[30] Each single word of a buddha’s speech, that voice with its ocean of qualities,

Bears all the purity of the speech of all the buddhas,

Sounds that harmonise with the minds of all living beings:

May I always be engaged with the speech of the buddhas!

c) Hearing the Turning of the Wheels of Dharma

[31] With all the power of my mind, may I hear and realise

The inexhaustible melody of the teachings spoken by

All the buddhas of past, present and future,

As they turn the wheels of Dharma!

d) Entering into All the Aeons

[32] Just as the wisdom of the buddhas penetrates all future aeons,

So may I too know them, instantly,

And in each fraction of an instant may I know

All that will ever be, in past, present and future!

e) Seeing all the Buddhas in One Instant

[33ab] In an instant, may I behold all those who are the lions of the human race—

The buddhas of past, present and future!

f) Entering the Sphere of Activity of the Buddhas

[33cd] May I always be engaged in the buddhas’ way of life and action,

Through the power of liberation, where all is realised as like an illusion!

g) Accomplishing and Entering the Pure Lands

[34] On a single atom, may I actually bring about

The entire array of pure realms of past, of present and future;

And then enter into those pure buddha realms

In each atom, and in each and every direction.

h) Entering into the Presence of the Buddhas

[35] When those who illuminate the world, still to come,

Gradually attain buddhahood, turn the Wheel of Dharma,

And demonstrate the final, profound peace of nirvana:

May I be always in their presence!

2.12. Aspiration to the Power of Enlightenment through Nine Powers

[36] Through the power of swift miracles,

The power of the vehicle, like a doorway,

The power of conduct that possesses all virtuous qualities,

The power of loving kindness, all-pervasive,

[37] The power of merit that is totally virtuous,

The power of wisdom free from attachment, and

The powers of knowledge, skilful means and samadhi,

May I perfectly accomplish the power of enlightenment!

2.13. Aspiration to the Antidotes that Pacify the Obscurations

[38] May I purify the power of karma;

Destroy the power of harmful emotions;

Render negativity utterly powerless;

And perfect the power of Good Actions!

2.14. Aspiration to Enlightened Activities

[39] I shall purify oceans of realms;

Liberate oceans of sentient beings;

Understand oceans of Dharma;

Realise oceans of wisdom;

[40] Perfect oceans of actions;

Fulfil oceans of aspirations;

Serve oceans of buddhas!

And perform these, without ever growing weary, through oceans of aeons!

2.15. Aspiration for Training

a) To Emulate the buddhas

[41] All the buddhas throughout the whole of time,

Attained enlightenment through Good Actions, and

Their prayers and aspirations for enlightened action:

May I fulfil them all completely!

b) To emulate the bodhisattvas: Samantabhadra

[42] The eldest of the sons of all the buddhas

Is called Samantabhadra: ‘All-good’—

So that I may act with a skill like his,

I dedicate fully all these merits!

[43] To purify my body, my speech and my mind as well,

To purify my actions, and all realms,

May I be the equal of Samantabhadra

In his skill in good dedication!

c) To emulate the bodhisattvas: Mañjushri

[44] In order to perform the full virtue of Good Actions,

I shall act according to Mañjushri’s prayers of aspiration,

And without ever growing weary, in all the aeons to come,

I shall perfectly fulfil every one of his aims!

2.16. Concluding Aspiration

[45] Let my bodhisattva acts be beyond measure!

Let my enlightened qualities be measureless too!

Keeping to this immeasurable activity,

May I accomplish all the miraculous powers of enlightenment!

Extent of the Aspiration

[46] Sentient beings are as limitless

As the boundless expanse of space;

So shall my prayers of aspiration for them

Be as limitless as their karma and harmful emotions!

3. The Benefits of Making Aspirations

3.1. The Benefits of Making Aspirations in General

[47] Whoever hears this king of dedication prayers,

And yearns for supreme enlightenment,

Who even once arouses faith,

Will gain true merit greater still

[48] Than by offering the victorious buddhas

Infinite pure realms in every directions, all ornamented with jewels,

Or offering them all the highest joys of gods and humans

For as many aeons as there are atoms in those realms.

3.2. The Thirteen Benefits in Detail

[49] Whoever truly makes this Aspiration to Good Actions,

Will never again be born in lower realms;

They will be free from harmful companions, and

Soon behold the Buddha of Boundless Light.

[50] They will acquire all kind of benefits, and live in happiness;

Even in this present life all will go well,

And before long,

They will become just like Samantabhadra.

[51] All negative acts—even the five of immediate retribution—

Whatever they have committed in the grip of ignorance,

Will soon be completely purified,

If they recite this Aspiration to Good Actions.

[52] They will possess perfect wisdom, beauty, and excellent signs,

Be born in a good family, and with a radiant appearance.

Demons and heretics will never harm them,

And all three worlds will honour them with offerings.

[53] They will quickly go beneath the bodhi-tree,

And there, they will sit, to benefit all sentient beings, then

Awaken into enlightenment, turn the wheel of Dharma,

And tame Mara with all his hordes.

3.3. The Benefits in Brief

[54] The full result of keeping, teaching, or reading

This Prayer of Aspiration to Good Actions

Is known to the buddhas alone:

Have no doubt: supreme enlightenment will be yours!

4. Dedication of the Merits of this Meritorious Aspiration

4.1. Dedication that Follows the Bodhisattvas

[55] Just as the bodhisattva Mañjushri attained omniscience,

And Samantabhadra too

All these merits now I dedicate

To train and follow in their footsteps.

4.2. Dedication that Follows the Buddhas

[56] As all the victorious buddhas of past, present and future

Praise dedication as supreme,

So now I dedicate all these roots of virtue

For all beings to perfect Good Actions.

4.3. Dedication towards Actualising the Result

[57] When it is time for me to die,

Let all that obscures me fade away, so

I look on Amitabha, there in person,

And go at once to his pure land of Sukhavati.

[58] In that pure land, may I actualise every single one

Of all these aspirations!

May I fulfil them, each and every one,

And bring help to beings for as long as the universe remains!

4.4. Dedication towards Receiving a Prophecy from the Buddhas

[59] Born there in a beautiful lotus flower,

In that excellent and joyous buddha realm,

May the Buddha Amitabha himself

Grant me the prophecy foretelling my enlightenment!

4.5. Dedication towards Serving Others

[60] Having received the prophecy there,

With my billions of emanations,

Sent out through the power of my mind,

May I bring enormous benefit to sentient beings, in all the ten directions!

5. Conclusion

[61] Through whatever small virtues I have gained

By reciting this “Aspiration to Good Actions”,

May the virtuous wishes of all beings’ prayers and aspirations

All be instantly accomplished!

[62] Through the true and boundless merit

Attained by dedicating this “Aspiration to Good Actions”,

May all those now drowning in the ocean of suffering,

Reach the supreme realm of Amitabha!

[63] May this King of Aspirations bring about

The supreme aim and benefit of all infinite sentient beings;

May they perfect what is described in this holy prayer, uttered by Samantabhadra!

May the lower realms be entirely emptied!

This completes the King of Aspiration Prayers, Samantabhadra’s “Aspiration to Good Actions.”

So, let me give you a moment to dedicate in your own way.

[Pause]

And with that, thank you, and I look forward to seeing you again.

[END OF TEACHING]

Note: to read footnotes please click on superscript numbers

Transcribed and edited by Alex Li Trisoglio