Alex Li Trisoglio

Public teaching given online in Madeira Park BC Canada

August 29, 2021

Part 1: 54 minutes, Part 2: 43 minutes, Part 3 (Q & A): 25 minutes.

Outline / Transcript / Video

References / Teachings Reviewed:

2020-12-11 – Vipassana For Beginners (Taipei)

2020-01-25 – View, Meditation and Action (Sydney)

2019-11-27 – Vipassana (Lhaktong) (Thimphu)

Note: Transcription in progress (65% complete – Parts 1 & 3 complete)

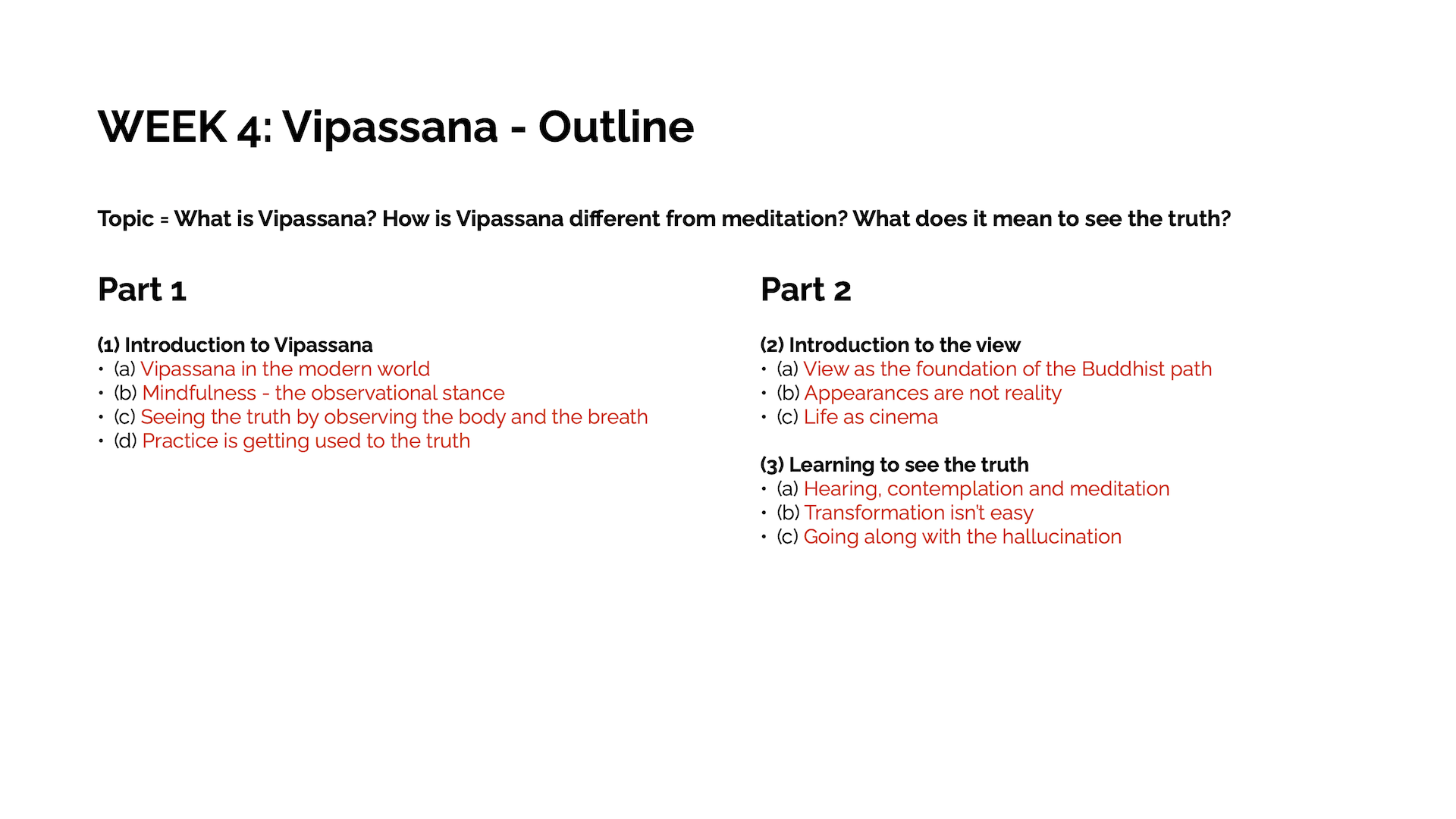

Outline

Part 1

(1) Introduction to Vipassana

(a) Vipassana in the modern world

Outline of Week 4

Well, good morning, everyone. And Good evening. Welcome to Week Four of the introduction to Buddhism. This week, we’re going to be talking about Vipassana. We’re going to start with an introduction to Vipassana. It will be quite experiential. We’ll follow where we started last time, with the idea [and practice] of the observational stance. We’ll explore a little bit of mindfulness of our body and our breath, and how that can lead us to the truth. And then we’ll talk about the idea of practice as a way of getting used to the truth.

In the second part, we’ll talk about view, and how that’s the foundation of the path in Buddhism. And in particular, the way that appearances are not reality, and how life can be seen as cinema. In the final part, [we’ll talk about] learning to see the truth, transitioning a little bit from the idea of Vipassana and view and into the idea of practice. How do we make this real for us over over the longer term?

Jon Kabat-Zinn and the origins of Vipassana in the West

I want to start by talking very briefly about how Vipassana is currently understood in the West. Because it has become very commonplace, and it’s used [seemingly] everywhere to treat stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Also to help with happiness, focus, productivity etc. And the current way of thinking about mindfulness in the West really started with Jon Kabat-Zinn, who is a professor emeritus of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. He was a Zen practitioner, a student of the Korean son Master Seung Sahn1For a biography of Jon Kabat-Zinn, see wikipedia.. And [in his medical practice] he was treating patients who had untreatable chronic pain. There was no medical way he could make their pain go away. And so he became curious, I wonder if there’s a way that rather than try to remove the pain, I can help them change their relationship to that pain.

And so he experimented with various forms of mindfulness, including physical yoga as well. And that turned into the now famous eight-week MBSR (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction) program. In 1979, he founded the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. And, as they say, the rest is history. His definition of mindfulness is still very much used in western [presentations] of mindfulness. He said:

Mindfulness is the awareness that arises from paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.

Mahasi Sayadaw and 20th century Burmese Buddhism

There’s another big strand of the way we approach mindfulness in the contemporary world, which came from what happened in Burmese Buddhism in the late 19th century and the 20th century, There were a number of reformers in Burma who were actually influenced by Western modernism, and wanted to make Buddhism more accessible for laypeople, starting with Ledi Sayadaw in the 1880s2Ledi Sayadaw studied as a monk in Mandalay but left after a great fire in 1883 destroyed his home. He returned to Tet Khaung, his childhood village in rural Burma, where he founded a forest monastery and began practicing, teaching intensive meditation, and writing Dharma books that were accessible to laypeople, thereby spreading Buddhist teachings and the traditional practice of Vipassana throughout Burmese society. See Erik Braun (2018) “The Insight Revolution” in Lion’s Roar, and also the article on Ledi Sayadaw in wikipedia. The beginnings of the Burmese Vipassana revival can be traced further back to the 18th century Burmese Theravada Buddhist monk Medawi, who wrote the first modern Vipassana manuals in the 1750s and thus may have been the first practitioner in the modern Vipassana movement – see wikipedia.. He popularized Vipassana meditation for laypeople. And then, in the early 20th century, Mahasi Sayadaw introduced something called the New Burmese Satipatthana method alongside S. N. Goenka and other teachers, who then became very influential because many Western students accessed them and their teachers.For example, in the US, the Insight Meditation Society was founded in 1975, by Sharon Salzberg, Jack Kornfield, and Joseph Goldstein, all of whom came from that lineage. And so American Buddhism [in general], not just mindfulness, is very influenced by that way of thinking. And we’ll talk more about that next week when we talk about the four foundations of mindfulness. But just to say that it is a way of approaching Buddhism that’s very based on mindfulness practice, paying attention to the sensations of the rising and falling of the abdomen during breathing, and observing carefully any other sensations or thoughts. It also includes some Buddhist teachings on causality and thereby [provides a path] to gain insight into the nature of mind the nature of reality. So it’s based on a very classical Theravada [presentation], the root teachings of Buddhism.

Contemporary mindfulness is focussed on physiology rather than truth and wisdom

Unfortunately, although Jon Kabat-Zinn was trained in Buddhism, and he says he espouses its principles, he also says he very much “rejects the label of Buddhist”3Boyce, Barry (May 2005). “Jon Kabat-Zinn: The Man Who Prescribes the Medicine of the Moment”. Lion’s Roar. and he says he “prefers to apply mindfulness within a scientific, rather than a religious frame”4Wilson, Jeff (2014). Mindful America: The Mutual Transformation of Buddhist Meditation and American Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 35.. I think given his influence in the field, that way of thinking has become quite consequential for the way that people in the modern world approach mindfulness, and by extension how they approach Buddhism.

He downplays the three marks of existence, which we touched on briefly in previous weeks, and we’ll talk more about today. Those are not something that can be measured scientifically. He’s focused on things that you can measure, changes in hormones, changes in body chemistry, in brainwaves. Stress, physiological markers, EEG, MRI machines, it’s a little bit like in business, we say, What gets measured gets managed. And I think that has given rise to a bit of a framing where “Buddhism is bad science is good”. And I think even more than that, you now see some, what I think are somewhat misguided attempts, to portray Buddhism as a science. Because I think there’s a bit of a feeling that we need to prove that we can be treated that way.

I think that’s not very helpful. Because the aim in Buddhism is different from this aim of stress reduction or [making improvements to] our physiology. Not that Buddhism is against that, of course not. But at the same time, you can’t measure truth or wisdom in an MRI machine. And the aim of the Buddhist path and the Buddhist practice of Vipassana is to see the truth — the truth of reality, the truth of our own minds. And I think that’s why many scientific people don’t want to go there. It sounds philosophical. It sounds religious, something that’s very much frowned upon in academia. But as we said, last week, the truth is not magical or mystical. It’s actually very simple. It’s too close almost, like our own eyelashes.

The meaning of Vipassana

So what does this word Vipassana actually mean? “Passana” is a Pali word that just means seeing, and “Vi-“ is a prefix that brings the context of seeing more, seeing extra, seeing something special. As Rinpoche says, [it’s about seeing] the real deal, the true colour. And this is deceptive because whenever we hear words like “insight” or “true colour”, we assume [that they must be referring to] something magical, something mystical, something more than we can ordinarily see. Which is not the case.

But nevertheless, we [are familiar with] the idea that appearance is not the same as reality. We know that a person may appear to be polite and gentle, but when we get to know them, maybe they’re not like that at all. Maybe the real deal is not the same as our superficial understanding. Vipassana is not the same as ordinary seeing, ordinary observation. And as we said before, yes, if you want to use Vipassana as a way of stress reduction, good sleep, better focus, better leadership, of course, it can help. But as Rinpoche said, that’s a bit like using gold leaf to wipe your bottom. If you want to relieve your stress and anxiety, as he said, Go wash your buffalo. It’s very soothing. Massage, soft music, things like that.

In Buddhism, we are focused on the root cause of your stress, your suffering. And here, the idea is that if you’re living a life of deception, either about yourself, or about other people, or about the world, then that’s either stress or it’s a cause of stress. We really believe you need to see the truth. So that’s what we’re going to talk about this week.

(b) Mindfulness – The observational stance

Appreciating our cognizance, our ability to observe and be aware

Let’s go back to the mind itself, the observer. We talked about this last week. We have this cognizance, this power of observing. We’re constantly seeing and hearing and sensing. A table can’t do this. But as Rinpoche said, we don’t do much to appreciate this observer. I was reminded of Thich Nhat Hanh’s lovely story of “The Joy of Non-Toothache”. He said, When you have toothache, all you can think about is how much you want it to go away. And when finally it goes away, maybe you’ve seen the dentist or taken a painkiller, for those first few hours after it goes, there is this wonderful experience, which he calls the”joy of non-toothache”. You really appreciate how much it’s gone. But that wears off. And after a few days, you’ve completely forgotten. You’ve lost that appreciation of the joy of non-toothache.

Similarly, I’ve had friends who’ve contracted COVID, and they’ve lost their sense of taste. And they said, it’s so strange not to be able to taste anything. There’s one woman who’s following these teachings, and she wrote to me to say how much she appreciates the transcripts, because, sadly, she’s lost her hearing. She’s never going to be able to hear the Dharma again. And she said, Without the transcripts, she’d really become disconnected from the teachings. So just pausing for a moment to appreciate what we have. We don’t often do that.

And of course, our awareness, our cognizance, is the root of all of that. And we’re going to talk about awareness, about observation. The observational stance is very much at the heart of mindfulness and Vipassana. And that requires us to be present, to be non-distracted, to pay attention to the present moment. Because if we’re thinking about the past and the future, we can’t observe what’s happening right now. Once again, Thich Nhat Hanh sums up the attitude nicely. He said:5In Thich Nhat Hanh (1975) “The Miracle of Mindfulness”.

If while washing dishes, we think only of the cup of tea that awaits us, thus hurrying to get the dishes out of the way as if they were a nuisance, then we are not “washing the dishes to wash the dishes.” What’s more, we are not alive during the time we are washing the dishes. In fact we are completely incapable of realizing the miracle of life while standing at the sink. If we can’t wash the dishes, the chances are we won’t be able to drink our tea either. While drinking the cup of tea, we will only be thinking of other things, barely aware of the cup in our hands. Thus we are sucked away into the future — and we are incapable of actually living one minute of life.

So I really want to encourage us to approach our practice with that attitude.

Paying attention to the observer

We have this observer. Let’s just take a moment to pay attention to this observer. As we said before, no need to sit straight or anything. Just look at it. What is it?

[60 seconds]

So we might call it “mind”. Perhaps scientists might call it “brain”. Jack or Jill or Wang or Dang, we give it names. But we have it. We don’t need to download it. We can’t lose it. It’s the most important part of who we are. So how can we not pay attention to it? Let’s look again, without any influence, without any beliefs, anything we’ve read in books, or taken from religion or science or philosophy. All that is useless, right? Just observe, fully, open-mindedly, without prejudice.

[30 seconds]

So that’s it. And that’s what we’re going to use. That cognizance, that observation, that observer. And we’ll talk more next week and in future weeks about how we how we can train it. But in a way it is our instrument. It’s like a chef has a knife to cut vegetables, or a scientist has an instrument to observe things. Our mind is our instrument. And so part of what we want to do is to sharpen our knife, to clean our instrument.

The dangers of naming and reification

But when we look, as Rinpoche said, we don’t want to find anything. We don’t want to name it, like in the Tao Te Ching, “The name that can be given is not the name”. Red Pine translates these lines as follows:6From Red Pine (1996) “Lao-Tzu’s Taoteching with Selected Commentaries of the Past 2000 Years”.

The way that becomes a way

Is not the Immortal Way

The name that becomes a name

Is not the Immortal Name.

As commentary, he offers the Buddha’s words from the Diamond Sutra:

He who says I teach the Dharma maligns me

Who teaches the Dharma teaches nothing.

Obviously, this is not intended to be nihilism. We’ll talk more about this in Week 6. But it’s inviting us to look at our habit of naming, reifying, solidifying — turning phenomena into nameable objects. And, of course, there’s a risk that we’re going to do that with our mind also. But knowing that risk, let’s just call it “observer” for now. And as we [may have noticed], it also observes itself. It has this remarkable capacity of self-awareness. We don’t need another observer. It’s like turning on a light in a dark room, you don’t need another light to see the one that you just turned on. We’ll talk more about that as well.

So as we said last week, We have this mind. We are stuck with mind. And it can be painful, we don’t always like it. There’s this feeling of stress, anxiety, unsatisfactoriness. And so with our control freak-like nature, we try to control it. We distract ourselves, we numb ourselves. Last week, we talked about how we numb and distract ourselves with TikTok, social media, or perhaps the desire to build super-tall skyscrapers.

We mistake words and concepts for the world

This week, I also want to talk about [how we numb ourselves with] concepts. Rinpoche said, “It’s called education”. That sounds strong as a criticism, because isn’t education something good? Well, yes, of course, it’s good. We need it. We need it to survive and thrive in the world. But I think we can forget how easily we reify. We get enmeshed in the web of language and concepts that we learn. We think we’re understanding, but actually we misunderstand. We mistake our words and concepts for the world.

There’s a lovely story about a famous experiment done with the Me’en people of Ethiopia, who were presented for the first time with photographs of people and animals7This story appears in Chapter 1 “It’s All Invented” in the 2000 book “The Art of Possibility” by Rosamund Stone Zander and Ben Zander.. A team of anthropologists were curious how would they respond. But they were completely unable to read the two-dimensional images. They felt the paper, sniffed it, crumpled it, listened to the crackling noises it made, even nipped off little bits and chewed them to taste it.

People in the modern world, we easily equate a photographic image with an object that is photographed, even though the resemblance is only very abstract. There’s a story of Pablo Picasso traveling by train once, and the man sitting opposite him said, Why don’t you paint people the way they really are? Picasso asked, What did he mean by that expression? And the man opened his wallet and took out a snapshot of his wife, saying that’s my wife. Picasso responded, Isn’t she rather small and flat?

So for the Me’en people, there were no photographs, even though they were in their hands, as plain as day. They saw nothing but shiny paper. It’s only through the conventions of modern life that we actually can read the photograph and see the image in the photograph.

I want to use that example just to start us off on a journey of exploration. What do we actually think we’re seeing? What is our view? Are we actually seeing reality for what it is? This is going to be a core question in Buddhism. Because as we said last week, yes, we have this mind, this cognizance, this awareness, but it is shrouded. It is covered with defilements, like a dirty window. And because of that, we get caught in mistaken views. emotions, ignorance. And our actions and reactions coming from that place become what are termed “non-virtuous actions”. We cause suffering for ourselves and for others. And so our aim then is to try and clear up, clear away these wrong views.

View and the Four Noble Truths

Let’s relate this to the Four Noble Truths:

1) The 1st Noble Truth is that we experience suffering and unsatisfactoriness., such as anxiety, stress, and depression. [And the everyday experience of not getting what we want, and getting what we don’t want].

2) The 2nd Noble Truth is that this [experience of suffering and unsatisfactoriness] is rooted in our clinging. Yes, that is right, and the additional point we’re going to make this week is that the clinging itself is founded on wrong views. So we’re going to talk more about view.

3) The 3rd Noble Truth is the result, and there is no change. It’s the state of the Buddha, the state of the Tathagata. As we discussed in Week 3, this is the cognizance [with all defilements removed].

4) The 4th Noble Truth is the path. We’re going to talk more this week about eliminating wrong views and establishing the right view.

And seeing the truth changes your attitude. Rinpoche gave a lovely example. Imagine a wife comes home one day and just briefly spot that her husband has a tail. One glimpse changes everything. All of a sudden, she’s asking herself, “Who am I married to? I saw it”. And in future when he comes home from work, the way she greets him will change. When he eats dinner, she’ll be wondering, Does he really like this food? Just one glimpse changes the attitude.

That’s also the way we want to think about the view and the practice of Vipassana. How, as we glimpse the truth, it will change our attitude.

In Buddhism, we are focused on the root cause of your stress, your suffering. And here, the idea is that if you’re living a life of deception, either about yourself, or about other people, or about the world, then that’s either stress or it’s a cause of stress. We really believe you need to see the truth. So that’s what we’re going to talk about this week.

(c) Seeing the truth by observing the body and the breath

Practice: Mindfulness of the body

So let’s approach this experientially in another way. There are many traditional meditations that [involve] mindfulness of the body, and we’ll just do one briefly. You don’t have to sit in any particular way. Whatever way you’re sitting or standing or lying, just observe your body.

Start with your toes. Just bring your awareness to your toes. You don’t have to do anything, no need to move them or change or wiggle them or anything. Just observe. Observe them.

Your feet.

Your ankles.

Observe your calves.

Feel the knees,.

Thighs. Maybe if you’re sitting on a chair, you can feel contact with the chair.

Hips.

What about your back? Perhaps you’ll notice whether you are sitting straight or slouching. Again, no need to change. Just observe. Just notice.

Fingers.

Hands.

Arms.

Notice your shoulders.

Neck. Is there some tension there perhaps?

Your head.

Observe your body as a whole.

Now bring your awareness back to the head.

Ears.

Eyes. Maybe you can even feel them in their sockets.

The mouth.

The nose. Maybe you can notice the movement of the breath coming in and out of the nostrils. Maybe you notice it’s slightly cooler on the in-breath. slightly warmer on the out-breath as it’s been warmed by the body.

Now notice the movement of the breath in the body, the chest and the abdomen.

Just follow the movement of the body as you breathe just for a few moments. Just noticing. Just observing.

[30 seconds]

Maybe you will become distracted. That’s okay. gently bring your awareness back to the movement of the breath in the body.

[30 seconds]

What do you notice? What do you observe?

[30 seconds]

Here are some things that you might well notice if you continue to do this observation of the body and the breathing. Perhaps you may already have noticed this.

• Whole/Parts: For example, one of the first things you might notice is that there’s no such thing as a whole. It’s actually parts. You might first think of your hand as a complete hand. But if you really observe, you’ll notice Wow, there’s blood, there are bones, there’s muscle, sinews, there are nails. It’s actually parts, there’s no whole there.

• Permanent/Impermanent: Another thing you’ll notice is what we might normally think of as permanent is actually impermanent. We might habitually think of the body as unchanging. But even just noticing the breath go in and out. Noticing that sensations that come and go. Noticing that we have a desire to shift our weight around. That saliva collects in our mouth. We swallow. Our eyes get dry. We blink.

• Satisfactory/Unsatisfactory: We notice that after a while, the body becomes uncomfortable. We want to shift and move. Any position is unsatisfactory.

• Independent/Dependent: We also start to notice that the body isn’t independent. We start to notice the support of our chair or cushion, whether or not we find it comfortable. We notice the temperature of the room, the ambient noise. Or if we practice for several hours, we’ll start to notice that we need food and water. We notice the need for fresh air. We might perhaps even notice that we’re dependent on the architect and the builder of our house. The fact that the roof hasn’t collapsed on us. So our experience, our very existence, is dependent [on many causes and conditions that are external to the self]. It is not independent.

Now we’re already starting to practice Vipassana. We’re looking beyond the surface appearances to notice something about their nature. And if you keep going, you’ll notice three truths. These are the three truths, [the three marks of existence], that we touched on already in previous weeks.

• Impermanence (anicca): The first is impermanence. Everything is always coming, going arising, decaying. Changing, drifting, shifting. You breathe out, it’s gone. There’s nothing magical about that. It’s just raw truth. We might think that change is bad, but change is also good. It allows fresh things to come in our life.

• Unsatisfactoriness (dukkha): The second is unsatisfactoriness. There’s no ultimate satisfaction in anything. Even things we enjoy, like ice cream. Too much makes us sick. We gain weight. Even finding exactly the right flavour and texture is so hard. And even if we do get the right flavour and the texture, and the right amount, the pleasure wears off. Everything is like this. In psychology we call it the “hedonic treadmill”. Even when you’re observing your breathing, maybe at the beginning it was nice just to pause and relax. But after a while we get fidgety, anxious, distracted, bored. We don’t want to spend time with our observer anymore. We feel there are things we need to do, we’re wasting time.

• Nonself (anatta): The third thing we’ll notice is nonself. As you observe your body and its parts, you’ll notice there’s no true identity, not even true characteristics. There’s nothing that’s truly thin or truly fat. Truly beautiful, truly ugly. All comes together with causes and conditions. Even your breath. Where does your breath start and stop? When you breathe out, where does it go? When you breathe in, what are you breathing in? Now with this summer of forest fires and air pollution and COVID, we’re all more sensitive to that. And supposedly with every breath, we’re breathing in one molecule of Julius Caesar’s last breath. Or Hitler’s. Maybe even the Buddha’s. When did it stop being his and start being yours? Likewise, I’m sitting at a table. It has legs. It has a top. There’s a cup [on top of the table]. But if I sit on my table, suddenly it has become a chair. It has no fixed identity as a table. It’s like the Me’en people not seeing the piece of paper as a photograph.

Now, you may ask, why do we use the body and breathing? There’s nothing holy about it, but it’s free. It’s always with you. And it’s very practical. By observing the breath, you can see these three marks. It’s also one of the traditional methods in the sutras. It’s an original Buddhist method.

And I know we use the word mindfulness [to describe practices like this]. But as I said earlier, there’s a difference between “Passana” which is seeing, and “Vipassana” which is seeing the truth. Because if you’re just mindful, if you’re just observing, but you’re not observing this real deal, these three marks, the nature, then you’re just present to your everyday worldly confusion and the unsatisfactoriness. You may see it, and that’s good, but you’re not yet moving beyond it.

As we practice Vipassana, our attitude to life will change

So if we keep doing this, what happens? Well, yes, our attitude changes, but that doesn’t mean we’re suddenly going to give up on our life. We can see the three truths of the body, but we’ll still exercise, we’ll still dress nicely, we’ll still use moisturizer. We’ll do the same things, but we’ll do them differently, with a different attitude.

Rinpoche gave the example of the sandcastle. Imagine it’s a beautiful sunny day at the beach. And there are some parents with their children building a sandcastle. They build a castle and then the tide starts to come in and starts to wash away the sandcastle. The kids, they might be upset, especially if this was the first time they built a sandcastle. But the parents, they knew the tide was coming. They really enjoyed building the castle. They had lots of fun with the kids. And they weren’t expecting lasting pleasure. They weren’t expecting a permanent sandcastle. You could say they were not attached, they had some form of renunciation. Of course, they have compassion for their children’s experience.

Sometimes we hear these three marks — the ideas of impermanence and unsatisfactoriness and nonself — and we read them as very negative or pessimistic. But not at all. It doesn’t mean once you understand these three marks that you suddenly become nihilistic or uncaring. Indeed, if you are, it’s a sign you have the wrong view.

Far from it, you’re still going to have fun with your children. You’ll still make your sandcastle big and beautiful. You’ll really make it nice. If anything, you’re more present. You’re less obsessed. You have more fun because you know the truth. You do a beautiful job, you have fun with your kids, and then you let go.

If ever you’ve seen Tibetan monks building sand mandalas, it takes them many days to do it. And at the end, they just destroy this intricate beautiful construction8Alice Yoo has a lovely photo essay “Tibetan Monks Painstakingly Create Incredible Mandalas Using Millions of Grains of Sand” at My Modern Met, and there is a lovely video of the entire process from construction to dissolution by the Wellcome Collection, part of “Secret Temple: Body, Mind and Meditation in Tantric Buddhism” available on YouTube. [Ed.: although making and then offering a sand mandala might appear to be about destruction if you are unfamiliar with the practice, it is actually a beautiful expression of offering and a practice of generosity and non-attachment9For additional information on the practice of offering the mandala, see Patrul Rinpoche / Padmakara Translation Group (1998) “The Words of My Perfect Teacher” (2nd Ed.) Ch. 4 “Offering the mandala to accumulate merit and wisdom” and Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse (2012) “Not For Happiness” Ch. 10 “Mandala Offering”. See also wikipedia.]. At the end they collect up all the sand and just make it into one mass. They are fully engaged, and then they dissolve and fully engage in the next thing. Just like Thich Nhat Hanh’s story of [washing the dishes and] making a cup of tea.

Presence as opposed to continuous partial attention

Whereas most of us, we’re not very good at that. We’re always multitasking. We have a continuous partial attention, and that causes tremendous unsatisfactoriness. And it’s not good for us or for others in a worldly sense either. I think it’s quite unusual to be doing one thing at a time. Many years ago, I was with Rinpoche in Kathmandu one Christmas and we had Christmas dinner and we were joined by a Tibetan Lama called Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche, a Khampa from East Tibet. He’s big and rather fearsome in his expression, but actually a very kind master. And I remember, we ate, we talked and at the end of dinner, he stood up, he turned around, and he walked out of the door. He didn’t do any sort of fond farewells or goodbyes or hugs or kisses.

And I was quite surprised. I’d never experienced that. And of course, it felt rude to my Western sensibilities. But Rinpoche clarified and said, No, for him, he’s there when he’s there. And then once it’s done, it’s done. It’s dissolved, and he moves on to the next thing. There wasn’t any hint of rudeness for him. He was just very present in whatever he was doing. I still remember that because it was so different from some of the ways we become so sentimental, so unable to let go and move on from one thing to the next thing. We’re always thinking of the last thing, thinking ahead to the next thing. Even at work, as we go from meeting to meeting, the last meeting is always on our mind as we move into the next meeting. How can we find a way to actually be present in what we’re doing?

Appreciating impermanence

I also wanted to talk a little about the idea of impermanence, the first of these three marks. For those of you who have seen the movie “The Dead Poets Society”, [these is a lovely scene] where Robin Williams is reciting a poem10“To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time”, a poem by Robert Herrick first published in 1648, available at The Poetry Foundation. See also commentary and analysis in wikipedia.:

Gather ye rose-buds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles today

Tomorrow will be dying.

I think we [are very familiar with] this idea if we think about it. Wow, yes, time is passing. Time is precious. Each day comes but once. [The contemplation of flowers as a reminder of the passing of time is perhaps most famously expressed in the annual flowering of sakara, or cherry-blossom, in Japan.11In Japan, cherry blossoms are an enduring metaphor for the ephemeral nature of life, which is embodied in the concept of mono no aware (literally “the pathos of things”, a Japanese term for awareness of impermanence). The transience of the blossoms and their exquisite beauty and volatility have often been associated with mortality and the graceful and ready acceptance of karma and impermanence. For this reason, cherry blossoms are richly symbolic, and often appear in Japanese art, manga, anime, and film – see wikipedia.] Another reflection on impermanence may be found in one of the most famous of Shakespeare’s sonnets, Sonnet 1812Available at The Poetry Foundation. See also commentary and analysis in wikipedia.:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimmed;

So far, so good. Shakespeare is pointing us to the natural state of things, impermanence, unsatisfactoriness. And you would think, actually, yes, that’s a beautiful reflection on impermanence. And then in the next and final part of the sonnet, that’s where we get into trouble. Because now he starts to express how his love for his beloved is different from this kind of impermanence. He continues:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wand’rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to Time thou grow’st.

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

I think that’s more typical of our usual experience. Love is blindness. Love is madness. Of course, we like to fall for that blindness and madness, we glorify it much as Shakespeare did. But we’re going to be disappointed if that’s how we enter into things. Rinpoche often jokes, there’s no such thing as a Buddhist marriage ceremony. And maybe actually, it would be better if we were to do a divorce ceremony when people got married, just to remind them that all things are impermanent. Like the sandcastle. But if we have that experience, that knowledge of three marks, then we can enjoy love, passion, obsession even, in a very different way.

Renunciation

But don’t fool yourself. This is hard. And that’s part of the reason that many people choose to have a monastic life to give themselves a bit more space to really reflect on the practice. I know that most of us are not monks and nuns. So we’ll have to reflect a little more how can we find a way in our everyday lives of giving us what it takes to see the three marks without getting caught up too quickly in the passions of our life.

But there’s also this idea that renunciation happens naturally through our life. As children, perhaps we love sandcastles, then we grow. As teenagers, maybe we like skateboards. And by that stage, we’ve lost interest in the sandcastle. Now, what matters is the skateboard. We become adults and then our interest is our houses, our jobs, our careers, our cars. Eventually, we retire. And as we grow older, perhaps what we’re left with, as Rinpoche says, is an interest in things like lace tablecloths and salt shakers. We’re definitely not attached to the skateboard. Spontaneous renunciation. We know this is going to happen if we think about it. We talked in the first week about purpose, and the regrets of the dying.

Is there a way we can cultivate this awareness and act upon it without having to wait to grow old? Well, yes. We can observe the three marks. We can familiarize ourselves with them. We can understand impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and nonself — and change our habitual way of relating to ourselves into others. And once we know the truth, that is a form of liberation, just like the parents with the sandcastle. We talked last week about a child watching a demon dance, the child is scared. But when they go behind the stage and see it’s just a person wearing a mask, then that’s the end of the demon. Another more familiar example, you’re having a nightmare. As soon as you know that you’re just dreaming, it’s finished. Even if you continue to dream, you’re no longer caught. Indeed, you might even play with it. I know lots of people love this idea of lucid dreaming. But until you know the truth, you’re a victim of that game.

Appreciating the profundity and simplicity of the truth

So yes, it’s a big deal in one way. Of course, knowing the truth [is a big deal]. But it’s also so simple in another way. And I think we’ll go back and forth between appreciating how important and what a big deal this is, but also having confidence in the simplicity. Having both can sometimes be a challenge. I think it doesn’t help when we hear words like “nirvana”. I think that has so many connotations of rainbows and heavenly music playing. It damages this idea that the truth is just so ordinary. But as Rinpoche said, sometimes we need the hype, because too many of us haven’t experienced the ordinariness of our lives. We haven’t experienced normality.

We talked last week about the lettuce rather than the salad with the Thousand Island dressing. The raw, uncooked, uncontrived nature. We don’t really spend time with that. And unfortunately, we tend to think that seeing the truth is very profound. And we tend to say to ourselves, “Oh well, I’m not profound. I’m just an ordinary person”. But when we do that, we distance ourselves from the truth, because we distance ourselves from this thing that we think is profound. It’s not. It’s the most ordinary thing. It’s just we’re not used to it.

When we see [the truth], it doesn’t mean we’re going to go to the mountains. It doesn’t mean we’re going to become renunciants. But it does change our attitude. How we see things will be different. Rinpoche likes to tell the story of his former secretary, who was a PhD biochemist. And she would always travel with lots of hand sanitizers and soap and disinfectants, because her training meant she would see germs everywhere.

And I think that’s the kind of thing we’re aiming for. We want to train our minds, so that we see the three marks in all phenomena. And of course, in ourselves. Now, that mindset of the sandcastle. If we can do that will develop this attitude of less attachment. Less craving. Less hope, less fear, more compassion.

The challenge of translating “anatta” (nonself)

I want to say in passing that this word “nonself”, the third of the three marks — which is “anatta” in Pali — is very difficult to translate properly. It’s often misunderstood as meaning “non-selfish”, as in generous. And when you look at the English dictionary definitions, it really doesn’t help because “selfless” means “having no concern for the self : unselfish”. And “unselfish” is defined as “generous”. Even the word “nonself” [has a meaning quite unlike anatta, because] it is defined as “material that is foreign to the body of an organism” [as in the way that our immune systems can distinguish cells that are “self” from invasive or foreign cells that are “nonself”].

That’s unfortunate, because in Buddhism the meaning of “anatta” is that there is no solid, unchanging core identity. Your “self” is not a solid or fixed thing. It’s not something that you can attach to because there’s no “thing” there. You’re dependent, you’re part of the world around you. It’s all part of a process, a system, a matrix. In Week Six, we’ll talk about how nothing is the way it appears. Everything is an illusion. But actually, if you can understand that your “self” is not a fixed, independent thing. If you reflect on that — perhaps a little bit like this idea of noticing what is your breath, what is not your breath, etc. — then you’ll start to understand interdependence.

You’ll start to see that the people around you matter. The world around you matters. You’ll naturally care more about ecology, about other people, about animals, about the impacts you create on the world, both positive and negative. You’ll care more about the products you buy, where did they come from? How were they made? How were people treated? When you dispose of them, what will happen? Will they be reused? Recycled? You’ll start to think in a much more systematic [i.e. systems-oriented], interdependent way. [Whereas today] many of us are still caught in this idea of some sort of isolated self at the centre of its own universe.

(d) Practice is getting used to the truth

Familiarization, training and mastery

One other thought just before the break is about the idea of practice and getting used to the truth. Again, unfortunately the English word “meditation” comes with associations of sitting straight, maybe doing some kind of practice as we just did. There are actually many different words in Pali and Sanskrit that all correspond in some way to the English word “meditation”. One of the most important words is “bhavana” in Pali or “gom” in Tibetan, which means “getting used to”.

For example, when we learn to drive we might start by going to a driving school where we learn the techniques. But we can’t stay in the school our whole lives, so we have to go to the streets. We see cats and dogs running everywhere, we encounter the other traffic. And once we learn how to drive, then of course, if we want, we can text, we can fix our lipstick, and we can turn around and chat to people in the backseat. Not that I’d recommend any of that. Just to say, we have a mastery of the technique. We’ve become familiar with it, we’ve internalized it. It has become part of us. That’s the sort of thing that we want with our approach to the Buddhist view.

There’s a lovely story about Picasso13There are several versions of this story. This is how the story is told by Maria Popova at Brainpickings.. He was sitting in a park sketching and a woman walked by and recognized him. She went up to him and pleaded with him to draw her portrait. He was in a good mood, so he agreed. He sketched and a few minutes later handed it to her. She was ecstatic. She gushed about how wonderfully it captured the very essence of her character and how beautiful it was. She asked “How much do I owe you?” He said $5,000. And she was taken aback, outraged. She asked, “How is that even possible? It only took you five minutes”. And he looked up, and without missing a beat he said, “No, madam. That took me my whole life”.

The English word “meditation” doesn’t convey this process of familiarization, of training, of mastery. And you’ll often hear Buddhists term themselves “practitioners”. This idea that we are works in progress, that we see our life as ongoing practice. We acknowledge that it’s not all going to be solved so quickly.

Vipassana is anything that brings you closer to the truth

And Vipassana is not necessarily just meditation, because it’s about seeing the truth. So it could be studying or contemplating a book. It could be a discussion with friends. Basically, anything that pulls the rug from under your feet. Anything that challenges your existing habits and ways of seeing that [go] against the three marks – i.e. [all the ways in which we don’t view] things as impermanent, unsatisfactory and nonself. Basically, Vipassana is any study or any practice that brings you closer to the truth.

Of course, traditional Buddhist practices can also be Vipassana. You can offer incense, you can offer a flower, you can offer a butterlamp. And if you’re doing that with the awareness of the three marks, or at least the motivation to see the three marks, then that counts as practice. So with that [motivation and attitude], you can of course, burn incense, go to the temple, shave your head, whatever.

And we can do Vipassana in our everyday life, of course. But the masters do still encourage us perhaps to go out of the kitchen and into a special space, maybe your shrine room if you have one or at least a little corner of the living room. Maybe from your house to the mountains, from the city to under a tree in the forest. We’re more likely to get closer to the truth if we’re sitting straight rather than lying in a hammock sipping on a tequila. Also, practically, because it’ll challenge our habitual thinking and associations. We don’t associate lying in a hammock with seeing the truth.

That’s not to say that we can’t [authentically practice Vipassana lying in a hammock sipping on a tequila]. It really is about being able to match the practice and its demands with the current level of our mind training. We’ll talk about this much more in future weeks when we talk about practice.

Traditional Buddhist techniques and rituals can also help

Rituals can also help. They provide structure. Because once you have a ritual memorized, once you have it as part of your unconscious memory, it frees up your mind to not have to focus on the task. And then you can observe the nature of the task, you can observe your awareness as you are carrying out the task. Mastery in any domain is like this.

If you want to play the piano, you keep practicing your scales, you practice a piece until the technique is no longer the issue, and you’re free to focus on the expression and interpretation. In martial arts, the coloured belts come first, where you learn technique. Then the black belts are about mastery and awareness, presence and expression. It is said14See the article “Black belt (martial arts) in wikipedia.:

The shodan (first degree black belt) is not the end of training, but rather a beginning to advanced learning. The individual now “knows how to walk” and may thus begin the “journey”.

Going back to the driving example, as a beginner you’re so focused on the technique of driving, changing gears using the brake using the accelerator. All of your conscious awareness is going into that. If you remember your first few weeks as a new driver, it’s very stressful. You haven’t yet been able to internalize [the technique]. The expertise is not yet unconscious. You can’t enjoy driving yet. But if you keep practicing, then you will.

Practice can be everywhere, all the time

It’s the same with our Buddhist practice. So we should have the aspiration that practice can be everywhere, all the time. It’s a motivation. It’s an attitude. You can do it everywhere. You’ve got a motivation and you’ve got an attitude all the time anyway, it’s just that most of the time you’re not aware of it. You’re not mindful. Now you have a chance to become aware and actually choose your motivation, choose your attitude, choose to be mindful of the three marks.

This won’t come naturally at first. It is unnatural. It is unfamiliar. As we said in previous weeks, it’ll feel wrong at the beginning, like anything that’s new. But you don’t have to quit your job. You can start right now. You don’t need to make excuses about not having time or money to practice. You don’t need an app, you don’t even need a cushion. You don’t need to set time aside. You don’t need lots of hours sitting or chanting mantras. It’s everywhere all the time.

You could even be doing Vipassana practice right now as you listen to me. You could notice, This is impermanent. This is not 100% satisfying. There’s no truly existing self or core identity to me, to you, or to these teachings. Just remember the sandcastle. And as Rinpoche said, a lot of the time the reason we don’t practice is because we make practice into this big and complicated thing. We don’t realize what practice actually is.

We just understood that it’s paying attention to what’s happening right now, with this attitude of seeing the truth, seeing its true nature. That’s practice. You can do it while chopping onions. You can do it while having an argument with your partner. Nevertheless, yes, the sheer busyness and flux of life can be overwhelming. So it can be helpful to deliberately simplify your environment to just focus more explicitly on this experience. We’ll talk about this more in future sessions. But for now, we’re going to take a 10 minute break.

[END OF PART 1]

Part 2

[Transcription in progress]

Part 3: Q & A

Welcome back for the questions and answers. I’d like to start with Sarah’s question, which is in the chat.

Nonself and unselfishness – how is “anatta” misunderstood?

[Q, Sarah]: Please could you say more about the translation of “no self”? How can the translation of [“anatta” as] “nonself” lead to the potential misunderstanding of not being selfish?

[A]: There are two different words in English. [To translate] “anatta”, if you look at the Pali or the Sanskrit, “atta” or “atman” are the words for “self” [or “soul” or “spirit” etc.]. And the word “an” is the negative particle. So “anatta” literally means “no self”15anattā (Pali: अनत्ता) or anātman (Sanskrit: अनात्मन्) includes meanings of “not self” (where “self” or ātman also means “spirit” or “soul”), “something different from self”, “another”, “devoid of self” – see anatta.. Atman means self. It also means something like an essence or core or a soul [or a spirit]. There’s a big debate in ancient Indian philosophy, including between the Buddhists and the Hindus, about what it might mean. In the modern world, it corresponds to the notion, whatever we might want to call it, that we all identify with some core element of who we are [and which Buddhism identifies as the cause of our experience of suffering and unsatisfactoriness]. The idea of a solid self. So whatever we want to call that “thing”, that’s what we’re trying to challenge with the [insight contained in the] third mark [of existence]. So “anatta” means “nonself” [or “no self” or “not self”].

I think the reason it’s often translated as “nonself” rather than “no-self” goes back to the example of the snake and the rope. As you may recall, the [example of the] snake and the rope is where we’re in a dark room, there’s a rope on the floor, and we misperceive it as a snake. We turn the light on, and we realize it wasn’t a snake. It’s actually a rope. So the translation is not “no snake”, even though that’s technically correct, because we’re not denying or refuting a snake. [It’s not there there is a snake we need to refute. There was only ever a rope]. There is no snake. It’s non-snake.

It’s the same idea when [talking about the] self. We see a self like we see a mirage in the desert. We’ll talk more about this in Week 6. It’s an appearance that has no basis. It has no foundation. In Buddhism, we’re not trying to get you to deny it [in a nihilistic way]. Because as an appearance there clearly is a self. We go through life. We probably woke up today with the same job, the same partner, the same house, that we had yesterday. So, there is a sense of continuity, which is conventionally what we mean by “self”. And the word “self” also has a lot of connection with the word “person”, which is a word we use to talk about legal responsibility and accountability, the rights and responsibilities of a person.

Going back to nonself, the challenge comes when we translate “anatta” into English, because if you do it literally, you’d either say “no-self” or “non-self”. A lot of people also like the word “selfless”, and you can see why that would be similar. The problem is, if you look at the dictionary [definition] of “selfless”, it has the meaning of “having no concern for self : unselfish : generous”16selfless – see Merriam-Webster., which is of course a wonderful thing. And yes, we practice generosity in the Buddhist path too. But that’s not what we mean by “anatta”.

And likewise, the translation [of anatta] as “nonself” [is also problematic]. Merriam-Webster gives the example of “material that is foreign to the body of an organism”17nonself – see Merriam-Webster.. So we can distinguish what is self and what is nonself. It’s a little bit like saying, if we have a disease, our immune system sees that as nonself. And part of what makes the immune system so magical is that it can differentiate between our own body cells and the cells that are not part of our “self”. And for people who have immune system disorders or autoimmune diseases, it’s when that ability [of the immune system] to distinguish self and nonself breaks down. So the word in English tends to be used in that kind of context, somewhat more biological in its nature, to differentiate what is part of us and what is not part of us. But it’s still being used very differently from the Buddhist idea of “anatta”. Because even [when used in this] biological sense, “nonself” still holds to the idea that there is a self. [It still holds to the idea that] there is a biological core, and all this other stuff is not part of it.

Why isn’t the magic show happening for the Buddha?

[Q, Lydia]: If the self doesn’t exist, then does the clinging to a non existence self exist?

[A]: Well, yes, that’s why we suffer. Again, [this clinging to a nonexistent self] doesn’t truly exist, because in Buddhism “true existence” means that something has an ultimate unchangeable status. And if that were the case, then ignorance would be permanent. There would be no possibility of enlightenment. So yes, there is clinging to a nonexistent self, but it’s very similar to clinging to the idea of the snake or seeing the demon before we realize it’s just a man wearing a mask. There’s clinging as long as there is ignorance. But remember, the ignorance is like the dirt on the window, and we can clean the dirt.

[Q, Lydia]: The next part of the question is: Since this all apparently exists, while not truly, where is this happening? is it happening somewhere?

[A]: That’s a big question. We would have to differentiate between “mind” and the “nature of mind” or cognizance. At the level of mind, yes, it’s happening in your brain, of course. At the level of the nature of mind, we come back to the “hard problem” [in philosophy of mind]: Is consciousness a property of the material body or is it something else? I think it’s fair to say that scientists and philosophers haven’t concluded an answer on that question. There are different arguments in both directions. Some would say that it’s all perfectly explicable simply within the materialist paradigm. Others say no, we need to have a universe which has some kind of consciousness as a primal element just like matter or energy. Often that view is called panpsychism.

[Q, Lydia]: The third part of the question: My relationship with my mother is getting so fraught with no end in sight. I just want whatever this is to stop as soon as possible. The happiness and desire not to see her in anguish makes me want to cut through it and see it in terms of what’s really happening rather than only what’s apparently happening. So to the best of my ability, I apply the view that it’s all just a magic show. She’s a magic show. I’m a magic show. And there is a backstage somewhere putting on the show that isn’t real. You further mentioned that for the Buddha, there is no show and no audience for him, nothing has happened. I find this aspect of the view harder to apply. Can you elaborate?

[A]: This is also tricky. The idea of seeing things from the Buddha’s perspective, [the nondual perspective without a subject or object]. The best I can offer [for now] would be to say it’s like the waves and the ocean. If you’re a sailor in a boat, then you can see the waves. But if you’re the ocean, then you don’t see the waves as waves, it’s all part of ocean. It’s a bit of a bad example. But the point is, for the Buddha, there are no “phenomena” that can be separated out [as identifiable things or objects] from the ongoing flux of reality. It’s nondual. There is no subject, there is no object. There’s no audience as subject, there’s no show as object. And therefore, we can’t even say there is anything happening per se. But the idea of “something happening” is itself a very dualistic framing, where there is a subject, an object and an action, and it’s very hard for us to step outside that and imagine what would a nondual perspective be [like]. So for now, I’ll just leave it and say we’ll come back to this in Week 6. Please continue to let this question trouble you. And let’s see if we can get any closer then.

Is cannabis detrimental to practice?

[Q, Elder]: Is cannabis detrimental to the practice? In which ways? I’m asking from a technical point of view, not a moralistic point of view.

[A]: I’m not sure when you say “technical”, if you mean from a biological and physiological [point of view] or whether you mean from a Dharma practice point of view. I’m not going to attempt a physiological answer, because I think you can look that up yourself. The physiological effects of cannabis are easy to read about and understand18For example, see reviews of the medical and physiological effects on cannabis at National Institute on Drug Abuse, WebMD and the Government of Canada. For a more in-depth review, see Sharma, Priyamvada et al. (2012) “Chemistry, Metabolism, and Toxicology of Cannabis: Clinical Implications”, Iran J Psychiatry. 2012 Fall; 7(4): 149–156 available at NCBI., for good and of course for evil19Ed.: I received a letter from someone who expressed concern that people might think I am saying that “cannabis is evil”.

As we have seen in previous weeks, Buddhists don’t believe in religious concepts like “sin” or “evil”. Buddhism views suffering as resulting from the root cause of ignorance, i.e. wrong views. The term “for good and evil” is English idiom that more simply expresses “agathokakological”, which means “composed of both good and evil”, from the Ancient Greek ἀγαθός (agathós, “good”) and κακός (kakós, “bad”) – see wiktionary. The intended meaning is that we cannot simply say that something is either “good” or “bad”.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn expressed this beautifully in his 1973 book “The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956”:

If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

— Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, “The Gulag Archipelago” – see wikiquote.. I know someone who took too much cannabis and had a severe schizophrenic breakdown afterwards. I know these things can happen also.

But in terms of what I think you’re asking, which is, How does it help or hinder your Dharma practice? Firstly, I would say it really depends what what vehicle (yana) [or tradition] of Buddhism you’re practicing. Because in the Theravada there is pretty strict discipline, even in the five vows, about not to take intoxicants. This is because it’s hard enough, as we hopefully saw today, to see the three marks even at the best of times — when we’re non distracted, when our environment is quite clear, and there’s not too much going on. And if you start to drink, if you start to do drugs, then your ability to maintain that kind of awareness, that kind of observer, it’s going to be more difficult.

Having said that, in the Vajrayana the relationship is very different. There are many stories of the great masters who would deliberately take substances, psychedelics, alcohol, whatever, as a way of distorting their mind and their emotions, but with the ability to observe the distortion. So that’s a little different, because if you can do that, and of course, I will caution all of us that very few of us can, then it’s completely different. Because then any of these substances can be part of your practice, they can help you realize how your ordinary perception is just one of many that your mind can produce. And I think that was very much behind that wonderful [William Blake] quote I gave earlier from Aldous Huxley’s “The Doors of Perception”:

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is: Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.

For a lot of people who are studying psychedelics, for example Michael Pollan’s lovely book “How to change your mind”, there is the sense of being really curious about the way that “reality” is not some direct correspondence between what’s “out there” and what’s happening in our heads. Actually, there’s all kinds of construction and creation and selective editing going on. It really is a virtual reality that our minds are producing for us, which has some resemblance and some connection to the world. But we certainly couldn’t say it “is” reality now. So it can sometimes really help one’s practice, to “mess with” that projection, so to speak, as a way of becoming less attached to one’s current projection.

A lot of people who take psychedelics talk about the experiences they have, and many of them describe those experiences in very spiritual terms, about how they saw their world and their life in a different way. And indeed, many of them came out of that [psychedelic experience] with a desire to take up a spiritual practice. Partly because, if you can’t generate this insight for yourself, and you keep having to rely on external substances, well, that’s obviously problematic. It’s much better if we can do practice, and then realize the view, carry the view, have it with us all the time when we need it. And if you do your Buddhist practice, that’s a way of getting to the insight about the constructed nature of reality without having to go through drugs and so forth.

In summary, I would say that I can’t really answer as to whether it’s good or whether it’s bad, because it really depends on you and your capacities as a practitioner. It may be something excellent for you. And it may be something which is very bad for you.

In passing, I would ask, Why cannabis? Why are you turning to that? Is it some hack to solve a problem that maybe could or should be solved by Dharma practice? Is it some attempt to find a relief for some symptom? Is it actually helping you? Is it actually providing more of a forest glade environment for you to practice in? Or is it just allowing you to turn away from difficulties in your life? So I guess that’s more for you to personally reflect on, and decide for yourself what feels right. And certainly Elder, both for you and Lydia, I’m more than happy to talk about this with you personally, if either of you would like to talk about your practice.

Can art be part of the Buddhist path?

[Q, Lydia]: Rinpoche seems to encourage creativity in his projects related to education and the younger generation. I believe you also mentioned art in general as something that can be used as part of the path. Is there a relationship between creativity in terms of both art appreciation and art making? And the nondual view?

[A]: I would say yes, definitely. [Let’s go] back to the the example of Stravinsky’s ”Rite of Spring”, where we had the the Bohemians, who welcomed new and challenging things, whereas the upper classes wanted things that were familiar, elegant, nice and gentle. I think a big part of nondual practice is the ability, as we‘ve said a few times, to challenge ourselves and to pull the rug from under our feet. It involves thinking out of the box. It involves creativity in our approach to life. And artistic practice, and of course art in all its forms, is wonderful for giving us different perspectives, different ways of seeing the world. Art challenges our assumptions, challenges our [habitual] framings. And that’s true whether it’s visual art or literature, poetry, dance, music — all the arts can do this. So yes, 100%, I’d strongly encourage [the practice and appreciation of] art in all its forms.

And even traditionally, [art as practice] is very well developed in the Chinese and Japanese forms of Buddhism. Things like painting, calligraphy, the drawing of the enso, flower arranging, poetry, haiku — all these art forms are also forms of practice. And it’s said that great calligraphy masters can see the state of your mind, and even your heart, by the form of your calligraphy. Likewise, in India and Tibet, there are lots of great traditions of sacred dance. It’s similar, [in that] the way a person is able to express physically gives you insight into their minds and their hearts. And even in the Western tradition, with art, classical music, with with all these art forms, if we know how to look — back to Vipassana — we can also see so much there.

Given the three marks, would it be good to see ourselves as fluid, a process?

[Q, Elke]: With the three marks in mind, is it helpful to view ourselves more as kind of fluid or a process rather than something static as we usually do?

[A]: Definitely, yes, I would say the ideal is to go beyond any kind of narrative or story or view of yourself at all. That would be the best. But as we said, to cross the river, we need a boat. So starting to undo anything which is fixed and solid will really help. Learning to see that the self is a work in progress, in other words, that it is something fluid, that it is a process — just that alone can really loosen things up. T

he only reason I’m not 100% celebrating that idea is that unfortunately we can also then get attached to the fluidity or to the process itself. We may say, even though it’s not fixed, it’s the process that I now identify with. So there could still be a form of identification taking place. It’s a little bit like, you know, the ancient Greek idea that a man can never put his foot in the same river twice. Because obviously, the individual molecules of water are always going to be different. But of course, we [may still] identify a river, which is itself a fluid process. We identify it as a thing. We give it a name, we know where it is. And so the danger is [that we might engage in a similar] identification with our “self” even as a fluid process.

So yes, if it helps you Elke to slowly but surely reduce your identification, I think it’s wonderful. But best of all, is to try and go beyond any kind of identification, hard though that is.

How to overcome feeling tired when we practice with open eyes?

[Q, Annie]: How to overcome easily feeling tired when we open our eyes, when we practice awareness with open eyes?

[A]: That’s a difficult question. I guess there are several answers. One answer is don’t worry too much about it. You don’t have to practice with open eyes. Although I think there is a counterargument. One reason the the northern schools of Buddhism, notably the Tibetan schools, practice with eyes open is that they want you to integrate your practice into your life. The southern schools, a lot of Theravada schools, [practice with] eyes closed or partly open, which is good for cutting out distractions. Because 80% or 85% of the information [we take in about the external world] comes through our eyes. But the trouble is that we want our practice to be usable in our everyday life. And in our everyday life, we’re going around with our eyes open. And so if you train yourself, if you habituate yourself, to only be mindful and aware, to only practice Vipassana, when your eyes are half-closed or closed, then you won’t be used to doing it when your eyes are open in ordinary life.

So my thought for you, Annie, is unless you have some eye problem [maybe practicing with open eyes is not itself the problem]. My question to you is, Do you normally go around the world feeling tired, with your eyes open, as you go through your day? If you do, then maybe you have some medical condition that needs help. But my guess is you may not, in which case then it’s probably more likely that you’re straining in your practice.

It’s a very common thing in practice, that we are either too tight or too loose in our practice. The “too tight” is when we’re straining too hard. we’re concentrating too hard. We’re trying too hard. We’re too tense. The “too loose” is when we’re a bit too lazy, unconcerned, sleepy, dozy. And either of those is considered a dualistic extreme in our practice. There is a famous story of Buddha talking to a player of a stringed instrument, who asked him, How should I practice? And Buddha said, Well, how does your instrument sound the best? And [the musician] said, Oh, when it’s neither too tight nor too loose, when the strings have just the right tension. And the Buddha said, Yes, it should be the same with your practice.

So as with all things in Buddhism, we are seeking this middle way, neither too tight nor too loose. So Annie, all I can say for now is maybe you can find a way of just noticing if you’re approaching your practice with a little too much tightness, a little too much tension. See if you can relax a little. And see if that allows you to practice with open eyes a little longer.

Thank you all once again. Have a wonderful week, and I look forward to seeing you next week.

Note: to read footnotes please click on superscript numbers

Transcribed and edited by Alex Li Trisoglio