Alex Li Trisoglio

Public teaching given online in Madeira Park BC Canada

September 5, 2021

Part 1: 60 minutes, Part 2: 49 minutes, Part 3 (Q & A): 22 minutes.

Outline / Transcript / Video

References / Teachings Reviewed:

2020-12-11 – Vipassana For Beginners (Taipei)

Note: Transcription in progress (46% complete – Part 1 complete)

Outline

Part 1

(1) The two-fold practice of shamatha and vipassana

(a) Introduction: Review of Week 3 and Week 4

Welcome

Good morning. Good evening, everyone. And welcome to Week 5 of the Introduction to Buddhism. Our topic this week is meditation. And in particular, we’re going to continue where we left off last week with vipassana. We’ll talk about the four foundations of mindfulness, which is the vipassana teachings as set out in the Satipatthana Sutta. We’ll start by talking about the twofold practice of shamatha and vipassana. And then we’ll go through the Four Satipatthanas, the four foundations of mindfulness, starting with body, then going onto feelings and sensations, then mind, and finally talking about the mindfulness of phenomena or what Rinpoche calls references.

When Rinpoche talked about the overall aim of meditation, he reminded us that there are two things we’re trying to do:

(1) First, to realize that we have the observer, that cognizance that we’ve talked about before. And in fact, to remind ourselves that this is the most important thing that we have.

(2) Second, to learn to recognize and then become free of the filters that distort our perceptions, and that prevent us from seeing reality as it is.

I’d like to do a brief recap of what we covered in weeks 3 and 4, since they very much lead into what we’re going to do today.

Review of Week 3

In Week 3, we talked about the observer, cognizance, which we sometimes refer to as “mind” or “awareness”. And we talked about why it is the most important thing that we have. It is our authentic nature, the spirit or the nature of the Tathagata, or the Buddha. And we learned that means having gone (or going) beyond samsara and nirvana, if we can realize this authentic nature, that is liberation, or enlightenment.

We also learned that Tathagata means “gone and arrived from where you have never departed”. So although we may not experience our Buddhanature today, we have never departed from it. But we don’t realize that we have it. We’re like a poor man living on top of a vast buried treasure right underneath his house. So we need to go on a transformational journey, like the hero’s journey described by Joseph Campbell, to discover what we already have. This is the Buddhist path.

We talked about authenticity, and how although we have this cognizance, this Buddhanature, most of the time it is covered, so we can’t see it properly, or at all. It’s like raw cabbage covered with Thousand Island dressing, or like a window covered with dirt. But even when our window is covered with dirt, it remains clean. The dirt is removable. It’s adventitious, something extra that is separate from the glass itself. It’s not an impurity that’s part of the glass. And because our window has always been clean, we can clean it. Underneath the dirt, there is always a clean window, we can be awakened from our confusion.

And the Buddhist path identifies this dirt as negative emotions, such as lust, anger, and delusion, which are themselves based on clinging and craving, all of which are rooted in wrong views. We experience unsatisfactoriness and suffering because we do not see reality as it is. We are ignorant about the reality of ourselves, other people, and the world around us. We have wrong views. But by identifying and then deconstructing these wrong views, we can clean the dirt from our windows and realize that we have this observer, this cognizance, which is the nature of our minds.

It might sound difficult, but it’s not actually that complicated. It’s like a child looking at a stage where there’s a performance. There’s a demon dance and the child gets scared. But the moment the child goes backstage and realizes that it’s just a man wearing a mask, that’s the end. That’s the end of that wrong view, the illusion of the demon. The child is now free.

Review of Week 4

In Week 4, last week, we had an introduction to vipassana, which is the Buddhist practice of learning to see the truth, learning to be free from the filters and distortions that prevent us from seeing reality as it is. We started to pay attention to the observer, this cognizance. We learned to practice mindfulness, to develop an observational stance towards our experience. And we started with the experience of our own body and our breathing.

We realized that when we observe and bring our awareness to our experience, we see that it has three characteristics:

• (1) Impermanence (anicca): The first is impermanence (anicca). Everything is changing, shifting, drifting, always in flux. Phenomena are always coming and going, nothing stays the same forever. You breathe out, it’s gone. But there’s nothing magical about that. It’s just the raw truth. And we might think change is bad, but change is also good. It allows fresh things to come into our life. Change is decay, but change is also growth. Change brings challenges, but it also brings opportunities. So that’s the first, impermanence.

• (2) Unsatisfactoriness (dukkha): Next, we saw [that our experience has the characteristic of] unsatisfactoriness (dukkha). Nothing is 100% satisfying. There is no magic potion that can make us live happily ever after. There is no philosopher’s stone that can turn lead into gold. Even the pleasure of our favourite ice cream wears off after a while. And we might look longingly at the beautiful kitchens and exotic sports cars of the rich and famous, we might imagine that our lives might be so much better if we had skin like our Instagram idols. But even if we were to live in the perfect house, after a while we would get fidgety, anxious, distracted, bored. We cannot escape our own minds. And as long as our experience of reality is built on distorted perceptions and wrong views, we will always end up with unsatisfactoriness, disappointment and suffering.

• (3) Nonself (anatta): The third thing we notice if we start practicing Vipassana is nonself (anatta). We started [by observing] the body, and we noticed there is no truly existing or unchanging self. There’s no true identity, not even any true characteristics. There’s no [truly existing] thing, [no core or essence] that’s truly thin or truly fat, truly beautiful or truly ugly. All these phenomena come together and arise based on causes and conditions. We realize they are just conventional labels and designations I am sitting at a table. It has legs, there’s a piece of wood on top, I have a cup of tea on my table. But if I were to sit on the table, then suddenly it has become a chair. The table is gone. It has no fixed identity as a table.

We learned last week about the Me’en people of Ethiopia, [and how] when they were presented for the first time with photographs of people and animals, they were completely unable to read the two-dimensional images. They felt the paper, sniffed it, crumpled it, listened to the crackling noises it made, even nipped off little bits and chewed them to taste it. For the Me’en people, there were no photographs in their reality. Even though they were holding them in their hands as plain as day, they saw nothing but shiny paper.

As we familiarize ourselves with the practice of vipassana, we begin to understand the extent to which our reality is constructed. Just because something appears a certain way to us, that doesn’t mean that it appears that way to others. And it certainly doesn’t mean that it’s real. Our experience of having a “self” may be very strong and persistent and compelling right now. But perhaps we might be starting to become open to the possibility that things are not always as they appear. Maybe the demon dance isn’t quite what we think.

(b) Meditation in Buddhism: the glass of muddy water

Week 5

So with that background, we come to Week 5, this week. We’re going to continue to explore the practice of vipassana, learning to become more aware of the ways in which we misperceive reality. And we’re going to continue to familiarize ourselves with the truth. We’ll also start by practicing shamatha, calm abiding, which brings the calm and serenity that many people associate with meditation. And more importantly for us as Buddhists, it allows us to stabilize our awareness so that we can better practice vipassana, and [better] observe our experience.

And then we’ll spend most of our time on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, as set out in the Satipatthana Sutta, which is one of the most famous of all the Buddha’s teachings. It sets out four domains of experience in which we can apply and practice vipassana, successively exploring deeper, subtler, and more profound aspects of our experience and our sense of self.

A glass of muddy water

So let’s begin with a classic example of a glass of muddy water. We can’t see anything through the glass. So what can we do? Well, the first thing we can do is we can stop moving the glass, just let the mud settle. And this is shamatha. If we stop moving and shaking the glass, then all the mud will settle to the bottom. The meaning of the word “shamatha” has two parts. ”Shama” means tranquility, calmness, rest, equanimity, and the absence of passion. And the “tha” means abiding, sort of stabilization. [So “shamatha” means “abiding in calmness and tranquility” or the common translation of “calm abiding”].

It’s perhaps a little bit like the feeling of peace and relaxation that we might experience after a massage or a good yoga class or perhaps a warm bath. But at some point, we have to get out of the warm bath. Our glass of water is going to get shaken up again. And very soon, all the dirt and the mud will be everywhere, it’ll be all muddy again. Yes, we can have another bath or massage tomorrow. But the only lasting way to get a glass of clean water is to remove the mud and the dirt.

Seeing the nature of the dirt and thereby freeing oneself from the dirt

And that is the purpose of vipassana. As we saw last week, vipassana means cleaning the mud, cleaning the dirt on our window. [“Passana” means “seeing” and] “vi-passana” has the meaning of seeing something extra, something special, the real deal, the true colour, the true nature. It is about seeing through or past or beyond the dirt, [seeing the nature of the dirt] and thereby freeing oneself from the dirt. We talked about this last week, we’ll go into it more deeply this week.

Shamatha and vipassana are basic elements of all Buddhist practices, from the simplest Zen meditation to the most complex Tibetan practices. From offering a single flower to cultivating love and compassion for all sentient beings. And there are many rich traditions of cultivating wisdom, mindfulness, and compassion in Buddhism, such as the practice of the Four Immeasurables and the Six Paramitas in the Bodhisattva path, and the vast skillful means of the Vajrayana path. But all that is for another time. Here, we’re just going to follow Rinpoche’s focus in his [public] teachings over the last couple of years, where he very much focused on shamatha and especially vipassana. Again, just to say these are the foundation of all Buddhist practices. And so if we can start to understand how these function, it’ll enable us to make much more sense of our Mahayana practice, our Bodhisattva practices, and our Vajrayana practices.

(c) Shamatha

Focusing and settling awareness on a specific object

So, let’s begin with shamatha. How do we practice this calm abiding? Well, it’s very simple. It really is all about focusing and settling our awareness on a specific object. It could be a Buddha, it could be a stone, it could be a flower, and so forth. Of course in the tradition, all the Masters recommend using a Buddha, whether a visualized one or an actual image. This helps with refuge, with bodhichitta, with tantra.

There are other kinds of shamatha practice that don’t actually use a specific object1See Alexander Berzin, “Achieving Shamatha”, Study Buddhism.. For example, we could be focused and remain undistracted on a state of love and compassion, not aiming at any specific being but extending to all beings, like sunshine emanating from the sun. You can also practice shamatha with the object of emptiness itself. Or even mind itself, not aiming at the objects of cognition as if they existed on their own. This method of focusing to attend shamatha is the one used in Mahamudra and Dzogchen, and actually is very similar to the way Rinpoche taught it. We’ll explore that more today.

Last week, we already started a shamatha practice when we used breath as the object of our vipassana practice. We introduced it in the context of vipassana, because we were looking into the nature of our breath and our body, but it was also a shamatha practice because whenever we became distracted, and our awareness drifted away from the breath, we brought the awareness back to our object of focus, which in that case was the breath. So let’s just very briefly practice that now.

Bring your awareness to the body. The feet, the legs, the hands, the arms, the torso.

The body as a whole.

The head, the eyes, the ears, the nose. Maybe you’re aware of the movement of the breath coming in and out of the nostrils. Maybe you notice it’s slightly cooler on the in-breath, slightly warmer on the out-breath.

Now notice the movement of the breath in the body, the rising and the falling of the abdomen. And just follow the movement of the breath in the body.

[30 seconds]

Maybe you become distracted. That’s okay. Gently bring your awareness back to the movement of the breath in the body.

[30 seconds]

So that was a very brief [practice]. But you can continue that for 5 minutes, 20 minutes, a couple of hours. That is the practice of shamatha. And as you keep going with that practice, you will progress to deeper states of concentration and clarity. They’re known as the jhanas, and they’re described in detail in the Pali commentaries.

Shamatha in other spiritual and religious traditions

And in fact, many other traditions also have practices like shamatha. It’s pre-Buddhist, and is by no means exclusive to Buddhism. For example, in Hinduism, the idea of shamatha with its single-pointed focus and concentration of mind is the same as the sixth limb of Ashtanga Yoga, which is Raja Yoga, which is concentration or dharana2See “Samatha: similar practices in other religions”, wikipedia..

Other meditation traditions, for example Transcendental Meditation, can also be considered shamatha, because there you have a practice of silently repeating a mantra. And although the TM organization says that focused attention is not prescribed, and that the aim is a unified and open attentional stance3See “Transcendental Meditation technique”, wikipedia., nevertheless it’s not vipassana, because we’re not focusing on trying to see the truth.

So yes, there are many other traditions and even in Christianity and other traditions, many religions have practices of contemplation with specific objects, or icons, religious images, candles, and so forth. All of which can help to cultivate this quality of calm abiding. They help the dirt settle to the bottom of the glass.

But in Buddhism, our purpose is not just concentration and calm, but seeing the truth. And for that, we need vipassana in order to clear away the dirt. And that practice is unique to Buddhism, although shamatha is often taught as the first stage in the practice, in order to strengthen our awareness and develop stability, which we can then apply to observing phenomena in vipassana.

(d) Practicing shamatha and vipassana together

Shamatha and vipassana are two aspects of practice, not two separate techniques

Shamatha and vipassana are practiced together. They’re not taught in the sutras as two separate techniques, but rather as two aspects of practice. And in the Pali Canon, the Buddha never mentions independent shamatha and vipassana practices. They’re always taught as two qualities of mind to be developed through meditation.

When [the Buddha] tells his disciples to go and meditate, he never says “Go do vipassana”, he always says “Go do jhana”, which is the Pali word for meditation. And in the few instances where vipassana is mentioned, it’s almost always paired with shamatha, not as two alternative methods, but as to qualities of mind that a person may gain or be endowed with, and that can be cultivated together4See Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997) “One Tool Among Many: The Place of Vipassana in Buddhist Practice”, Access to Insight..

Similarly, Ajahn Brahm, a teacher from the Thai forest tradition, says5See Ajahn Brahm (2006) “Mindfulness, Bliss and Beyond: A Meditator’s Handbook”. Ajahn Brahm reaches his conclusions based on the sutras MN 151: 13-19, and AN IV: 125-27 – see “Samatha: samatha and vipassana”, wikipedia.:

Some traditions speak of two types of meditation, insight meditation (vipassana) and calm meditation (shamatha). In fact the two are indivisible facets of the same process. Calm is the peaceful happiness born of meditation; insight is the clear understanding born of the same meditation. Calm leads to insight and insight leads to calm.

Their purpose is to develop insight and ultimately to attain liberation

And in the Theravada tradition, shamatha is ultimately used to develop insight into the three marks of existence that we have talked about already – anicca, dukkha and anatta [impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and nonself]. [As Robert Buswell writes in the Encyclopedia of Buddhism]:6See Robert Buswell (2004) “Encyclopedia of Buddhism”, Macmillan Reference, USA. pp. 889–890. See also “Samatha: samatha and vipassana”, wikipedia.

Jhana [i.e. meditative state, wholesome mental state – heightened awareness and reduced distraction] is induced by shamatha, and then jhana is reflected upon with mindfulness, becoming the object of vipassana, realizing that jhana is marked by the three characteristics. Buddhist texts describe that all Buddhas and their chief disciples used this method.

So the meditative state of jhana is induced by shamatha, then jhana is reflected upon and observed with mindfulness, becoming the object of vipassana. Then it is seen that jhana is marked by the three characteristics. And that, in turn, leads to insight and ultimately to liberation. So that’s the background to these practices. We’re not going to go deeper into shamatha right now, but please, the questions are open. So if anyone has any questions, don’t hesitate to ask.

(e) The four foundations of mindfulness

The Satipatthana Sutra: “The Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness”

We are going to turn now to the Satipatthana Sutra. The name means “The Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness”, and it’s one of the most celebrated and widely studied discourses in the Pali Canon of Theravada Buddhism7The sutra is Majjhima Nikaya 10, and several translations are available at Access To Insight, including by Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Nyanasatta Thera, and Soma Thera. See also “Satipatthana Sutta”, wikipedia.. It’s also the foundation for all contemporary Vipassana practice in the modern world. And famously, the Buddha declares at the beginning of the sutra:8From MN 10 “Satipatthana Sutta: The Discourse on the Arousing of Mindfulness”, translation by Soma Thera, Access to Insight.

This is the only way, O bhikkhus, for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation, for the destruction of suffering and grief, for reaching the right path, for the attainment of Nibbana, namely, the Four Arousings of Mindfulness.

So obviously, it’s a good thing for us to practice. Just remember what we’re trying to do here, our twofold purpose. First, we’re trying to pay attention and become aware of our observer. We have this cognizance, this observer. It’s our nature. Second, with vipassana we’re trying to observe phenomena fully, without interference, open-mindedly. And as we said last week, the observer is there all the time. Right this moment, you are conscious of something. Let’s pause for a moment and find out. What is that?

[30 seconds]

So this is it. Our cognizance. Our observer. We’re going to use it as we might use another instrument like a knife, or like a scientist might use a microscope. And [we aim to practice] observing without influence. Without theories [such as those from] religion, science, or politics. Observing directly, without a story, without trying to interpret or make sense. We’re not trying to confirm or find anything that we have read about or theorized about. It’s raw observation. Raw mindfulness. Or as Rinpoche said, raw awareness9In Talk 6 of “Vipassana for Beginners“, his teaching given in Taipei on December 12, 2020, he said:

So here in the classic Buddhist technique of vipassana, which also has many varieties, what we are beginning with is based on the four mindfulnesses or four awarenesses, I should say.. And by the way, it’s beyond our scope today, but for those of you who are wondering why he emphasized “raw awareness” rather than “raw mindfulness”, that’s the difference between the Dzogchen or Mahasandhi tradition and the Mahamudra tradition10Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche writes:

According to the words of Künkhyen Tsele Rinpoche, also called Tsele Natsok Rangdröl:

Mahamudra and Dzogchen

differ in words but not in meaning.

The only difference is that Mahamudra stresses mindfulness

while Dzogchen relaxes within awareness.

Mahamudra stresses mainly mindfulness. “Mindfulness” or “presence of mind” means to apply mindfulness or watchfulness, while Dzogchen relaxes into awareness; this is the mere difference. As it is said, “In Dzogchen the ultimate view is to relax into awareness,” which refers to nonfixation, nongrasping — [to remain] in the continuity of nongrasping.

See “Comparing Mahamudra and Dzogchen”, September 11, 2020, Lion’s Roar.. Nevertheless for our purposes [right now], “mindfulness” and “awareness” are both good.

The meaning of satipatthana

The word “satipattana” means the “establishment of mindfulness”, the “presence of mindfulness”, or alternatively “the foundation of mindfulness”11See “Satipatthana Sutta: Title translation and related literature”, wikipedia.. What does that mean? The word “sati”in Pali means mindfulness. And Bhikkhu Bodhi explains the word “upatthana”12The word “satipatthana” is a compound of sati, “mindfulness”; and either paṭṭhāna, “foundation,” or upaṭṭhāna, “presence.” The compound term can be interpreted as sati-paṭṭhāna (“foundation of mindfulness”) or sati-upaṭṭhāna, “presence of mindfulness”. According to Anālayo, the analysis of the term as sati-upaṭṭhāna, “presence of mindfulness,” is a more etymologically correct derivation as upaṭṭhāna appears both throughout the Pali Canon and in the Sanskrit translation of this sutta; whereas the term paṭṭhāna is only found in the Abhidhamma and post-nikaya Pali commentary. See Analayo (2006) “Satipaṭṭhāna – The Direct Path to Realization” and also “Satipatthana Sutta: Title translation and related literature”, wikipedia. as follows:13See “The Nature of Mindfulness and Its Role in Buddhist Meditation: A Correspondence between B. Alan Wallace and the Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi, Winter, 2006”, available at Rimé Shedra NYC.

The word upaṭṭhāna has the sense of “presence, standing near, attendance upon.” It seems this word was chosen because it conveys the impact that the practice of sati has upon its objective domain: it makes the objective domain present to the mind, makes it “stand near” the mind, makes it appear clearly before the mind. One might even ascribe upaṭṭhāna to the subjective rather than the objective side of the experience: it is the mind’s activity of attending to the object, the awareness of the object. Upaṭṭhāna can also mean “setting up,” and this is what one does with mindfulness.

The four satipatthanas

There are four domains or four broad categories to which we are invited to apply our mindfulness. Going from the more gross to the more subtle, from what is probably the least important, as Rinpoche said, to the most important. And here Rinpoche gave the example of an Americano, which is coffee and water, basically diluted espresso. He said it’s basically “bad watered down coffee”, but marketing people don’t like saying that. Actually, the the term Caffè Americano (also known as Americano) is Italian for “American coffee”, and there is a popular story that the name has its origins in World War II when American G.I.s in Italy would dilute espresso with hot water to approximate the coffee to which they were accustomed14See “Caffè Americano”, wikipedia..

In any case, the point is that an Americano has to have at least espresso and water as elements. And Rinpoche is saying that similarly, as we think about the elements or aspects of our experience and our awareness — when we think about self and phenomena — there are four different things which were invited to look at. First, we’ll go through these four satipatthanas quickly [and then we’ll talk about each of them in more detail]:

(1) Body (kaya): first is body (kaya). This includes the five senses, it includes tactile sensations, physical sensations, the body itself, breathing. We have already talked about this.

(2) Feelings/sensations (vedana): next is feelings or sensations (vedana). Those are the sensations aroused by perception. The sensations could be pleasant, they could be unpleasant, or they could be neutral. Psychology would call this the “valence” or the “hedonic tone”. The touch of a feather might be pleasant, or it might be ticklish and unpleasant. This [second satipatthana] refers to the raw tone of sensations before any emotions or narratives or stories. It doesn’t mean feelings in the sense of emotions, it means feelings in the sense of sensations.

(3) Mind (chitta): the third satipatthana is mind (chitta). This refers to all mental events. So [it includes] thoughts, also emotions, dreams, imagination. And in particular, it includes [awareness of] the presence or absence of the three poisons of greed, anger, delusion. Mind is such a big topic in Buddhism and the later schools of Buddhism developed much richer and more complex theories of what mind is about. But we won’t go into that today. We will just talk about the very simple awareness of mind.

(4) Dharma/phenomena/references (dharmas): the fourth of the satipatthanas is dharmas, which has two different meanings. It can mean the Dharma teachings themselves. And actually in the Satipatthana Sutta, various elements of the Buddhist teachings are listed as objects of mindfulness, including the Seven Factors of Awakening and the Four Noble Truths. And the Seven Factors of Awakening include mindfulness itself [as one of the seven factors], so in this fourth satipatthana, we are starting to come into meta-awareness or metacognition. We are starting to be mindful of our mindfulness itself. We are also becoming aware of the presence of the Four Noble Truths in all that we see. Seeing the truth everywhere, in all phenomena.

The second meaning of dharmas is “phenomena”, or as Rinpoche said, it can also mean “references” or “views”. He gave the example that if we think that tiny feet are beautiful, but you have a shoe size 14, you’ll be very upset. If you think a flat belly is good, you might walk around all day trying to suck in your belly, paranoid you might forget to do that. Likewise, phenomena include all our values, ideas, democracy, socialism, red party, green party, yellow party, Trump lover, Trump hater. According to the Mahayana and Madhyamaka, all phenomena are just projections [that arise] due to our own references, our own views.

So once we understand that, we see that when we talk about dharmas or phenomena, this fourth satipatthana actually includes all phenomena, all references, all views [i.e. everything that is part of relative truth]. And indeed, [since the relative truth includes] the Dharma path itself, the teachings, the practices, even nirvana, even enlightenment — these are all included as part of [the fourth satipatthana]. So we can start to see how these two definitions start to come together, phenomena and dharma. But Rinpoche cautions us that when people in the west talk about vipassana, it includes body and feelings, most commonly, but very rarely mind or phenomena.

Observing the four satipatthanas: an example

Maybe [it might be helpful] to give an example of these four satipatthanas. Imagine you’re going to a fashionable public event like the Met Gala, a black tie charity fundraising event in New York15The Met Gala, according to Vogue:

Affectionately referred to as “fashion’s biggest night out,” the Met Gala 2021 is a fundraising benefit for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The event welcomes stars, young creatives, and industry paragons.

See “The 125 Best Met Gala Looks of All Time”, Janelle Okwodu, September 1, 2021, Vogue..

• [Body]: You look at your shoes, and you see how shiny they are, you see the light reflecting. You notice the completely smooth surface where you have shined them. You noticed your tuxedo is soft and silky to the touch. This is all form or body.

• [Feelings/sensations]: As you look at your shoes, as you run your fingers against the sleeve of your tuxedo, you experience a pleasant sensation in your body. The shoes are beautifully shiny and elegantly proportioned. It’s just lovely to look at. It gives you a sort of warmth, an uplifting kind of feeling. The tuxedo feels very pleasant to the touch.

• [Mind]: Maybe you start to feel pride as you start to imagine how people are going to think you’re well dressed. Maybe your mind is wandering to how you’ve been a little lonely during the COVID lockdown, and you’re hoping you’re going to meet someone special. Maybe you might even find love here at this Gala.

• [Dharmas/phenomena/references]: Maybe you [decided on] this outfit, because you’ve been studying all the previous Met Galas and looking at the best dressed men. And you’ve put together your outfit in a way that you feel pushes the boundaries, but not too much. You think it’s stylish and elegant, but edgy enough to be interesting.

And you can see from this example how one might get caught in any or all of these four aspects of experience. But likewise, if you can start to see the three marks in any of them — if you can see that any of these four aspects are impermanent, unsatisfactory, and they have no self — then it can start to break down the whole illusion.

(2) Mindfulness of body

(a) Mindfulness of body – recap and practice

Recap

Okay, so returning now to body. As we already said, [the first satipatthana] includes all the things we normally associate with our form. 34 inches, six pack, arms, legs. And here we’re only going to be practicing a gross version. We’re not going to go into detail, like our sense organs. The bodily faculty of vision is much more than our eyes, even in the traditional Buddhist teachings, let alone in modern neuroscience.

Of course, our body is a very big part of who we are. Who is sitting here? Who went to the toilet just now? Who is getting hungry? It’s like the water in the Americano. So we’ll observe the body, no prayers, nothing mystical. And when we are aware of the body, it’s just noticing, just observing, just being aware — no narrative, no story. Nothing like “I have a body”, because that’s now moving into narrative and self-talk. It’s no longer observing the body. Just be aware. We don’t need theories.

Practicing mindfulness of body

We can practice in two ways:

• (1) Awareness of physical form: At times just be aware of parts [of the body] — nostrils, eyelids. Pay attention to those. Have you ever observed just how amazing they are? Sometimes you might go from the tips of your toes to the top of your head. Sometimes from your head to your toes. Sometimes from a finger on your left hand to a finger on your right hand. Sometimes the whole body.

• (2) Awareness of breathing: If that’s all a little too abstract for you, then bring your awareness to breathing. Just be aware of breathing in and out. And notice the way that in giving these instructions, Rinpoche is not trying to give us a fixed routine or a fixed form. He’s giving us an invitation to be creative, to keep our practice fresh, not to turn it into yet another habit. This is his approach to all practice, and it’s great to practice this way even here. So let’s just do this for a moment.

So sit straight. You can blink your eyes if you need to. Don’t do it deliberately. Don’t move or adjust your position. Don’t cough, don’t scratch. Rinpoche used to say, Don’t even swallow as saliva collects in your mouth. Let yourself drool. We’re not going to insist on that. But really, the more discipline you can apply, the more you can notice the body itself.

And this practice is a lot like the shamatha practice. But here we’re adding the awareness of the nature of the body and the breath. We’re not just seeing, not just seeing the surface, “passana”, we’re looking more deeply. We’re doing the vi- passana. We’re observing that our body, our physical form has these characteristics, these three marks of impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and nonself. So let’s do a very brief session, just a minute.

[1 minute]

Just be aware of the body.

And as we saw last week, as you continue to be aware, to observe, you will see the impermanence, the movement of the body, the movement of the breath. You’ll notice the unsatisfactoriness. And you’ll notice there is no self to be found.

(b) Internal and external mindfulness

Observing external forms

Now, what’s interesting is that, as Rinpoche said, when we’re doing meditation or mindfulness of the body, we don’t generally observe things like Taipei 101, the skyscraper behind him when he was teaching in Taiwan. For me, there is a tree behind me, a Douglas-fir. But I don’t necessarily observe it. I may have a general idea that it’s there. But I’m not observing it. Kaya, which is the domain of the first satipatthana, means “body” but it also means “form”. It’s more general. It refers to all physical forms.

And actually, even in the Theravada Vipassana, we observe both self and others. Other people, other forms outside us. [As Bhikkhu Analayo notes:]16See Analayo (2006) “Satipaṭṭhāna – The Direct Path to Realization” and Analayo (2013) “Perspectives on Satipatthana”. See also “Satipatthana: practice”, wikipedia.

All versions of the Satipatthana Sutta also indicate that each satipatthana is to be contemplated first “internally” (ajjhatta), then “externally” (bahiddhā), and finally both internally and externally. This is generally understood as observing oneself and observing other persons.17Analayo notes that this interpretation is supported by Abhidharma works (including the Vibhaṅga and the Dharmaskandha) as well as by several suttas (MN 104, DĀ 4, DĀ 18 and DN 18) – see Analayo (2006) and Analayo (2013), opp. cit. See also “Satipatthana: practice instructions”, wikipedia.

Going beyond a narcissistic and self-focussed practice of mindfulness

Of course in the Theravada, we’re much more focused on observing persons, and the Mahayana we extend that much more to also observing phenomena18Ed.: when establishing the Madhyamaka view, part of the Madhyamaka critique of the view of the early Buddhist schools is that they focus on the selflessness/emptiness of the person, but they do not fully and completely establish the selflessness/emptiness of phenomena, thus leaving a residue for ego-clinging and ignorance to inhabit. See, for example, Chandrakirti’s Madhyamakavatara.. But even so, it’s not just about self. The “internal” vipassana is looking at self, “external” Vipassana is observing others. And then “internal and external”, both, is the system as a whole. The whole field, the relationship between internal and external. So we start to move now to a much more nondual practice, going beyond self or other, to observing self and other, ideally simultaneously. We’ll talk more about that next week.

And by comparison, I would say most contemporary mindfulness practice is almost completely self-oriented. One could say it’s quite narcissistic. I focus on my own body in such a way that reinforces my “self”, and downplays everyone and everything else. This is a much more general critique of the contemporary self-help movement, namely that it ends up reinforcing narcissism19See, for example, Will Storr (2017) “Selfie: How We Became So Self-Obsessed and What It’s Doing to Us”, and Alexandra Schwartz “Improving Ourselves To Death”, January 8, 2018, The New Yorker. And of course, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s prescient analysis of “spiritual materialism” – how the spiritual path itself can become subservient to our narcissism and ego-clinging – for example in his 1973 book “Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism”.. So even in just this first satipatthana, the mindfulness of the body, there’s a very big difference from the way that vipassana is practiced in the contemporary West, or indeed how meditation in general is practiced. There’s much less focus on “self” awareness in Buddhism, and much more focus just on awareness.

(c) Observation vs vague idea

We’re no longer observing once objects of awareness become vague phenomena

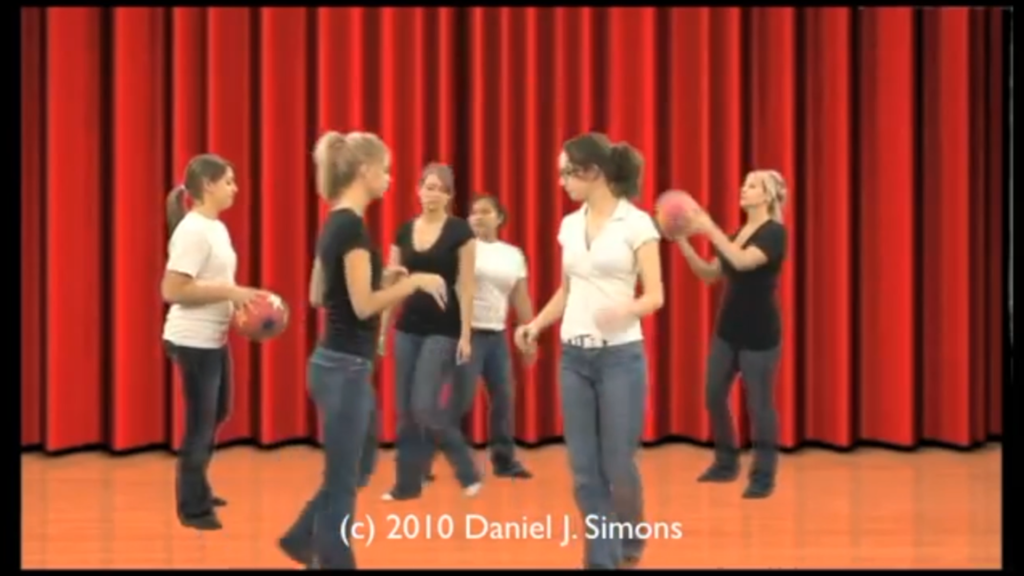

Let’s continue to explore Rinpoche’s point that right now we’re not really observing, we just have a vague idea [of form]. As he said, if we were really to observe a building like Taipei 101, we would see details that we’re not currently paying attention to. For example, its greenness, its spaciousness, so many things. The raw observational details. And this is also a big subject in western psychology. I want to show you a short video by Professor Daniel Simons, who is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Illinois20See “Daniel Simons”, wikipedia.. He studies awareness and attention. I’ll just show you the video and let you draw your own conclusions.

[Please watch the video before reading further. It’s less than two minutes long].

When I first saw this video, I was really quite delighted by it. Let’s just spend a moment thinking about this idea of vague impressions. Because usually we go straight to seeing a phenomenon, a labelled object. [We “see” a vague phenomenon rather than paying attention to the observational details right in front of our eyes]. So for example, in that video:

• There are several people throwing a ball. But instead of counting six people, it just becomes a “group” of people. It becomes a vague phenomenon. And so we don’t notice when one person just disappears.

• There is a curtain in the background. And it is red at the start, but it just becomes classified as “background” in our mind. A vague phenomenon. So we completely miss that when it changes colour from red to gold.

• We are focussed on the players in white, not those in black. So when a black-coloured gorilla enters, even though it’s pounding its chest right in front of us, we don’t even notice.

This is a very widely [researched and replicated] finding in psychology. So just to reinforce the point that Buddhism is trying to make here, we have to train our awareness, our observer. Even though we have it, our distraction and our ability to get caught up in wrong views are going keep us from seeing what’s actually going on. And in particular, once the object of awareness has become a vague phenomenon – a concept or idea – we have stopped paying attention.

Observing the upper left-hand brick

Let’s turn to a different example. This is a lovely story about observation from Robert Pirsig’s book “Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance”21Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values is a book by Robert M. Pirsig first published in 1974. It is a work of fictionalized autobiography, and is the first of Pirsig’s texts in which he explores his “Metaphysics of Quality” – see wikipedia.

Pirsig received 121 rejections before an editor finally accepted the book for publication—and he did so thinking it would never generate a profit. It was subsequently featured on best-seller lists for decades, with initial sales of at least 5 million copies worldwide. The title is an apparent play on the title of the 1948 book “Zen in the Art of Archery” by Eugen Herrigel. In its introduction, Pirsig explains that, despite its title,

“It should in no way be associated with that great body of factual information relating to orthodox Zen Buddhist practice. It’s not very factual on motorcycles, either.”. It’s a story about a student who is finding it difficult to write an essay22Ed.: This story was paraphrased somewhat in the live teaching. The version below is the one in Pirsig’s book..

He’d been having trouble with students who had nothing to say. At first he thought it was laziness but later it became apparent that it wasn’t. They just couldn’t think of anything to say.

One of them, a girl with strong-lensed glasses, wanted to write a five-hundred-word essay about the United States. He was used to the sinking feeling that comes from statements like this, and suggested without disparagement that she narrow it down to just Bozeman [Ed.: Bozeman is a city in Southern Montana in the Rocky Mountains]23Robert Pirsig taught at Montana State University. The city museum has a notable collection of Tyrannosaurus rex specimens – see wikipedia and “Siebel Dinosaur Complex”, Museum of the Rockies.

When the paper came due she didn’t have it and was quite upset. She had tried and tried but she just couldn’t think of anything to say.

He had already discussed her with her previous instructors and they’d confirmed his impressions of her. She was very serious, disciplined and hardworking, but extremely dull. Not a spark of creativity in her anywhere. Her eyes, behind the thick-lensed glasses, were the eyes of a drudge. She wasn’t bluffing him, she really couldn’t think of anything to say, and was upset by her inability to do as she was told.

It just stumped him. Now he couldn’t think of anything to say. A silence occurred, and then a peculiar answer: “Narrow it down to the main street of Bozeman.” It was a stroke of insight.

She nodded dutifully and went out. But just before her next class she came back in real distress, tears this time, distress that had obviously been there for a long time. She still couldn’t think of anything to say, and couldn’t understand why, if she couldn’t think of anything about all of Bozeman, she should be able to think of something about just one street.

He was furious. “You’re not looking!” he said. A memory came back of his own dismissal from the University for having too much to say. For every fact there is an infinity of hypotheses. The more you look the more you see. She really wasn’t looking and yet somehow didn’t understand this.”

He told her angrily, “Narrow it down to the front of one building on the main street of Bozeman. The Opera House. Start with the upper left-hand brick.”

Her eyes, behind the thick-lensed glasses, opened wide. She came in the next class with a puzzled look and handed him a five-thousand-word essay on the front of the Opera House on the main street of Bozeman, Montana. “I sat in the hamburger stand across the street”, she said, “and started writing about the first brick, and the second brick, and then by the third brick it all started to come and I couldn’t stop. They thought I was crazy, and they kept kidding me, but here it all is. I don’t understand it.”

There’s something quite important here about noticing our own habits around observing, around getting caught in generalizations, getting caught in vague ideas, and not paying attention. So in all the phenomena of our life, all the people in our life, what is that top left-hand brick of the Opera House? How can we start to really see things, rather than just our vague impressions?

Subjective experience and objective reality – the story we tell is not what really happened

Now, apart from phenomena being vague and unobserved, there’s that there’s another way we fall prey to vagueness and lumping things together. And that’s when we fail to separate the observational data from our interpretation, our story, the phenomena. So for example, we probably all have an idea about what it means for someone to be rude. But have we really considered what we’re observing what we’re paying attention to when we label another person as rude?

I grew up in the UK, to an Italian father and a German mother. Three very different cultures. And for those of you who know a little about European culture, you will know that the English culture and the Italian culture are quite different. In England, if you’re having a dinner party, one is considered polite when one doesn’t interrupt. There’s decorum. Interrupting and talking over people is considered highly rude. Whereas in Italy, it’s very different. There, the culture is very extroverted, and actually engaging, interrupting, and talking over is a sign of just how much fun you’re having, how much you’re enjoying the conversation.

So let’s imagine for a moment how these four aspects of mindfulness might play out, if I were an English person — which indeed I am — and I was having dinner with an Italian friend, who started interrupting me:

• [Body]: First I would notice body. Behaviours. I would notice his voice talking over me. His interruption.

• [Feelings/sensations]: I would notice that my body is starting to tense up. Maybe I’m getting a little flushed. It’s not a pleasant sensation.

• [Mind]: In my thoughts, I start to experience my friend as rude. Maybe I start getting upset. Maybe I remember the last time I was in Italy, and how I didn’t really enjoy myself because everybody was like this.

• [Phenomena/references]: If you were to ask me, why these things are in my experience, I’d say, Well, you know, English manners and culture are superior. It’s really important for parents to bring up their children well, to be polite, and well-mannered.

I hope you realize that of course I don’t really believe this. [I’m trying to portray a caricature of a certain type of English person].

Of course, if I were not a vipassana practitioner, I probably wouldn’t be noticing any of those things. I might just turn to my friend and say, “Look, I find you to be very rude. And I’ll request that in future, Please, could you listen to me more carefully and not interrupt.”

Now, if I were an Italian having dinner with an Italian friend, perhaps I would notice the same external behaviours, although perhaps even then I might be paying less attention to how much my friend was saying, and perhaps more to the expression of joy on his face, maybe the smiling the laughter, the twinkle in his eyes. But then the second, the third, the fourth satipatthanas would all be different. Instead of telling him how much I was finding him to be rude, and how upset I was, probably I would tell him, I was delighted and I was so happy that he was enjoying the conversation so much.

Our subjective phenomena are real but not real

So there you have an example of two identical sets of external behaviours, but two completely different reactions. [Ed.: Indeed, although the objective observable behaviours are identical in these two cases, the subjective phenomena are completely different. This example might perhaps help to illustrate why in Buddhist Madhyamaka philosophy, truth is determined in terms of the subject rather than the object]. So as a vipassana practitioner, as I start to observe and to pay attention, I can start to see that it’s not the external behaviour that’s driving my experience and my reaction. I can start to see how it’s all constructed and invented. I start to see the anicca, the dukkha, the anatta — the impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, the fact that there is no true nature or self or identity to this experience. [I start to understand that the phenomena I observe in the practice of the four satipatthanas may be “real” to me, but they’re not ultimately real as an unchanging, independent, objective truth. And as I apply this awareness to my “self”, I am cultivating prajña or wisdom].

This is an example of a very practical application of vipassana. Just learning to see that what we think is happening in the world and what we’re perceiving is not actually what’s driving our interpretations and our reactions. It’s possible to cultivate a very different interpretation or reaction for the same set of behaviours. [And once I accept that my phenomena – my subjective perceptions and experiences – arise as a consequence of my own views, I can begin to take accountability for them. This is an important step towards self-mastery, as we discussed in Week 2: Self Mastery. Cultivating awareness and skill in this area can make a huge difference to the quality of our relationships and our life as a whole]. As we said in Week 2, we can learn to cover our own feet with leather, rather than having to change the whole world and cover the world with leather.

(d) Observing people as people

The root of all cruelty

I would also like to talk a little about one other application of observing the body, observing form. And this is perhaps more of a Mahayana application. When we think about bodhichitta, when we think about compassion, all too often when we think of other people, we just have a vague idea of them. We don’t actually observe them. We think of them in terms of vague categories like gender or race, or physical characteristics like short or tall or what have you.

And then we judge them, just like an Englishman might judge the manners of his Italian friend. [We don’t see them for who they actually are, much like the way we may not see the gorilla, the changing colour of the background, or the person leaving the group]. And I think it’s really important for us to learn to see past these judgments and to observe people for who they are. I’d like to read an excerpt from a lovely piece by Paul Bloom in The New Yorker a few years ago, called “The Root Of All Cruelty?”:24Paul Bloom “The Root Of All Cruelty?”, November 20, 2017, The New Yorker.

An episode of the dystopian television series “Black Mirror”25Ed.: The episode is “Men Against Fire”, S03E05 – see wikipedia. begins with a soldier hunting down and killing hideous humanoids called roaches. It’s a standard science-fiction scenario, man against monster, but there’s a twist: it turns out that the soldier and his cohort have brain implants that make them see the faces and bodies of their targets as monstrous, to hear their pleas for mercy as noxious squeaks. When our hero’s implant fails, he discovers that he isn’t a brave defender of the human race—he’s a murderer of innocent people, part of a campaign to exterminate members of a despised group akin to the Jews of Europe in the nineteen-forties.

The philosopher David Livingstone Smith, commenting on this episode on social media, wondered whether its writer had read his book “Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others” (St. Martin’s). It’s a thoughtful and exhaustive exploration of human cruelty, and the episode perfectly captures its core idea: that acts such as genocide happen when one fails to appreciate the humanity of others.

One focus of Smith’s book is the attitudes of slave owners; the seventeenth-century missionary Morgan Godwyn observed that they believed the Negroes, “though in their Figure they carry some resemblances of Manhood, yet are indeed no Men” but, rather, “Creatures destitute of Souls, to be ranked among Brute Beasts, and treated accordingly.” Then there’s the Holocaust. Like many Jews my age, I was raised with stories of gas chambers, gruesome medical experiments, and mass graves—an evil that was explained as arising from the Nazis’ failure to see their victims as human. In the words of the psychologist Herbert C. Kelman, “The inhibitions against murdering fellow human beings are generally so strong that the victims must be deprived of their human status if systematic killing is to proceed in a smooth and orderly fashion.” The Nazis used bureaucratic euphemisms such as “transfer” and “selection” to sanitize different forms of murder.

As the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss noted, “humankind ceases at the border of the tribe, of the linguistic group, even sometimes of the village.” Today, the phenomenon seems inescapable. Google your favourite despised human group—Jews, blacks, Arabs, gays, and so on—along with words like “vermin,” “roaches,” or “animals,” and it will all come spilling out. Some of this rhetoric is seen as inappropriate for mainstream discourse. But wait long enough and you’ll hear the word “animals” used even by respectable people, referring to terrorists, or to Israelis or Palestinians, or to undocumented immigrants, or to deporters of undocumented immigrants. Such rhetoric shows up in the speech of white supremacists—but also when the rest of us talk about white supremacists.

It’s not just a matter of words. At Auschwitz, the Nazis tattooed numbers on their prisoners’ arms. Throughout history, people have believed that it was acceptable to own humans, and there were explicit debates in which scholars and politicians mulled over whether certain groups (such as blacks and Native Americans) were “natural slaves.” Even in the past century, there were human zoos, where Africans were put in enclosures for Europeans to gawk at.

Early psychological research on dehumanization looked at what made the Nazis different from the rest of us. But psychologists now talk about the ubiquity of dehumanization. Nick Haslam, at the University of Melbourne, and Steve Loughnan, at the University of Edinburgh, provide a list of examples, including some painfully mundane ones: “Outraged members of the public call sex offenders animals. Psychopaths treat victims merely as means to their vicious ends. The poor are mocked as libidinous dolts. Passersby look through homeless people as if they were transparent obstacles. Dementia sufferers are represented in the media as shuffling zombies.”

I think it’s worth pausing just to notice our own observation, not just of our self but of other persons, other beings [including animals]. To what extent are we practicing lovingkindness and compassion? Are we able to see beyond whatever judgments and references we might have? Can we really be impartial? So with that, we shall take a ten minute break. I will see you after the break.

[END OF PART 1]

Part 2

[Transcription in progress]

Note: to read footnotes please click on superscript numbers

Transcribed and edited by Alex Li Trisoglio