Alex Li Trisoglio

Public teaching given online in Madeira Park BC Canada

September 12, 2021

Part 1: 53 minutes, Part 2: 66 minutes, Part 3 (Q & A): 15 minutes.

Outline / Transcript / Video

References / Teachings Reviewed:

2021-08-03 – Poison is Medicine (Halifax)

2020-06-21 – Kuntuzangpo (Bir)

2020-06-05 – Heart Sutra (Bir)

2020-01-25 – View, Meditation and Action (Sydney)

Outline

Part 1

(1) Nonduality – Introduction and Review

(a) Review of the path

Welcome

Hello everyone, good morning. Good evening. Welcome to Week Six of Introduction to Buddhism. And this week we’re going to be talking about nonduality. We’ll start with a review, an introduction. We’ve covered much of this before, but I think it will be helpful just as a foundation for what we’re going to talk about today.

We’ll then talk about how nonduality compares to some of the background of our thought and our philosophy in the modern world. Then we’ll talk about nonduality in the Buddhist path. Going through the view, meditation and action, and talking a little also about the result.

What is nonduality?

Nonduality means “not-two”, “not dual”. And all Buddhist paths consider themselves to be nondual. Indeed, all Indian religions, philosophies and spiritual paths consider themselves to be nondual. Avoiding the extremes of dualism is considered to be a fundamental element of a correct path. But the way that nonduality is understood and interpreted is more refined and sophisticated in some paths than others.

We have talked already about the way of thinking about the path in terms of view, meditation, action, and result. Any path has these elements. And they’re different, of course, for each path:

• Result: the result is what is the aim of the path? What will we realize or obtain if we follow this path?

• View: the view is what is truth? What are our underlying assumptions and beliefs about reality that will guide us on the path that are the foundations for our path?

• Meditation: meditation is about how are we going to familiarize ourselves with this view? What are the different practices that we can follow to do that?

• Action/conduct: action is how should we behave in our lives, in our work, in our relationships, if we want to stay true to this path, to this view.

And as we’ve seen already in the past weeks, in Buddhism:

Result

The result we variously call it nirvana, enlightenment, Buddha, Tathagata. Sometimes we talk about it as realizing the truth, when there is no more dirt on our window, when we’re able to rest without disturbance and distraction in the cognizance or awareness that is the nature of our minds. This is the state of the Buddha.

And we can contrast that with our current result, the result that we experience by living our ordinary worldly samsaric lives. Yes, there are all the ups and downs, excitement and disappointment, hope and fear, pleasure and pain, success and failure. But our experience is pervaded by unsatisfactoriness and suffering. We don’t feel like we’re making the most of our lives. Our days get filled with petty frustrations and meaningless activities. We feel like we’re going round and round in circles. This is samsara.

View

The view, the foundational Buddhist view, is shared by all Buddhist schools. We’ve talked quite a lot [in previous weeks] about the three marks of existence — anicca (impermanence), dukkha (unsatisfactoriness and suffering) and anatta (nonself). That is the truth. In Buddhism, that is the Dharma itself, both in the sense of truth and in the sense of the teachings that set out this truth. And if we realize this truth and internalize it, so that it is present for us every moment, then we are awakened.

But if we have wrong views, then we end up creating and then clinging to a solid and permanent self that we want to nurture and protect. And this gives rise to craving, and then negative emotions and actions. And then we’re back to our ordinary world of experience that we call samsara. With pleasure and pain, and all the rest.

Meditation

We have talked about meditation [quite a lot in Weeks 4 and 5]. The different paths of Buddhism collectively offered vast diversity of different forms of practice and meditation, different skillful means to familiarize ourselves with the view, and to cultivate the three trainings. These are:

• Shila: ethical discipline, including training ourselves in compassion.

• Samadhi: meditative concentration, mindfulness, nondistraction.

• Prajña: wisdom or discriminative awareness..

In modern psychology, we would call these deliberate practices or intentional practices. And our practice will often progress more rapidly with the support and feedback from a community of fellow practitioners. Again, modern psychology we call that a community of practice or an intentional community. In Buddhism, this is the Sangha.

In previous weeks, we’ve introduced shamatha and talked in some detail about vipassana. And [we’ve talked about how] these practices are foundational to all the Buddhist paths in the three vehicles or the three yanas — the Shravakayana, the Mahayana, and the Vajrayana — in the sense that all of the Buddhist practices will include:

• Shamatha: cultivating the ability to be present, nondistracted, aware of what is going on right now.

• Vipassana: cultivating the ability to see not just surface appearances but the truth. The truth of self, others and phenomenon. Their nature, the nature of [the three marks of existence]: anicca, dukkha and anatta.

We’ve introduced these practices as they were presented in the Pali suttas, and as they were practiced and continue to be practiced in the Shravakayana, the Theravada path. There have subsequently been many other paths in Buddhism, of course including the Bodhisattva path of Mahayana Buddhism, with the four immeasurables, the six paramitas and so forth. And the vast and diverse set of practices of Vajrayana Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism.

And of course, as with all phenomena, Buddhism itself is marked by the characteristic of anicca or impermanence, growth, change. The underlying truth of the Dharma, the underlying goal of awakening to the state of the Buddha has not changed. But much like our modern world is pervaded by technological innovation. founded on the work of scientists and entrepreneurs, there has been tremendous innovation in the technologies of Buddhism — the practices, the methods, the paths. And there are now so many different authentic ways we can approach Buddhism. We are at a unique point in the history and development of Buddhism, that they are all available and coming to the modern world together. And this, of course, gives rise to complexity and perhaps confusion and misunderstanding. But there is an incredible richness and opportunity there as well, if we can learn to see it.

Action/conduct.

We haven’t talked as much about action and conduct. We’re going to cover [these topics further] in the final two weeks. But we have already observed that in Buddhism, we accept widely different lifestyles, including:

• Monastics: renunciants and monastics, the simple life of a monk or a nun in a monastery.

• Householders: householders of all kinds, from great bodhisattvas and saints, kings and queens and warlords, to ordinary families living ordinary lives.

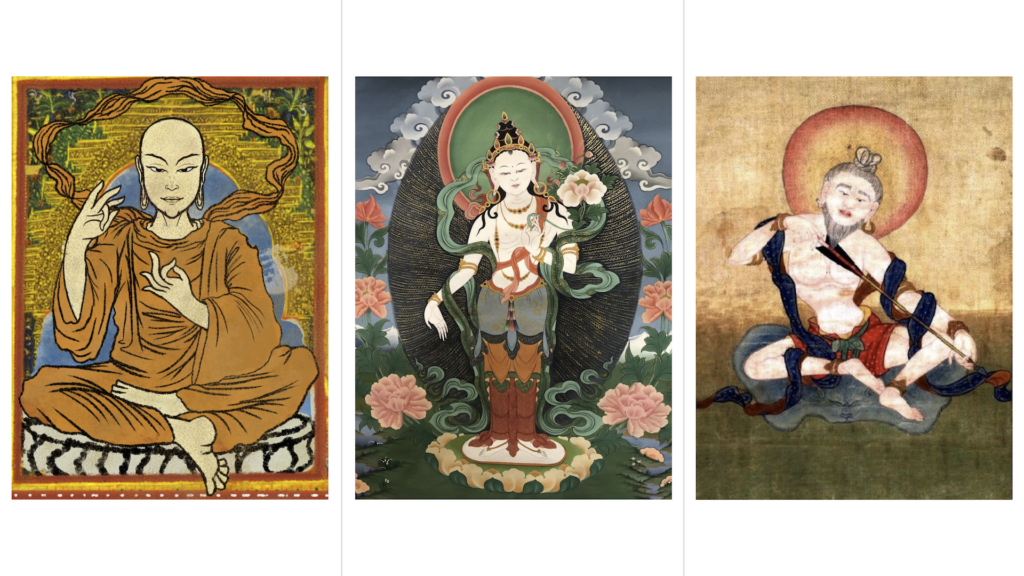

• Mahasiddhas: and then the great mahasiddhas and wanderers. We’ve talked about figures like Saraha, Naropa, Tilopa, and the Arrow-Making Dakini, the half-time prostitute, half-time arrow maker who was Saraha’s teacher — these are people who live their lives free from constraints of worldly and societal norms.

(b) Nondual awareness

I’d like come back now to ask, What if we were really looking at all of this from a nondual perspective? How might we approach this framework of view, meditation action and result?

Result

The result is the same. We seek to awaken to the state of the Buddha, to realize the truth.

View

The view, of course, is nonduality. And this is based on anatta or nonself, [which is] one of those three marks we have already talked about. But it does get extended in some subtle and important ways. In the basic forms of Buddhism, we establish the selflessness or the emptiness of the person, but not necessarily the selflessness or the emptiness of all phenomena. The earliest Buddhist schools still believed that external objects and mental representations were real.

But in the nondual view of the Madhyamaka, neither reflexive awareness, nor internal cognitive aspects, nor external objects can be established in any way as possessing intrinsic characteristics. All dharmas lack intrinsic existence. Emptiness applies not just to the self, but to all phenomena, including the Buddhist path – even the state of the Buddha, and even enlightenment itself. And lest we conclude that emptiness must itself be the ultimate truth, Nagarjuna demonstrated in his Mulamadhyamakakarika that emptiness is also emptiness.

This is this is obviously a very big topic. But for our present purposes, we can say that the ultimate truth in Buddhism is that there is no ultimate truth to be found. The so-called “right view” is the understanding that all views are wrong views. And in particular, we can speak of the wrong views of eternalism and nihilism, which are the two basic ways we can go wrong, the two sides that we can fall from the Middle Way.

Meditation

Now meditation. As we’ve explored in previous weeks, we can bring the nondual view to any and all methods of meditation. We can familiarize ourselves with the view through basic satipatthana practices such as mindfulness of our breathing, or through any of the Mahayana or Vajrayana practices. All practices are acceptable.

However, we can also familiarize ourselves with the nondual view without engaging in any specific behaviours. We talked about this in a couple of ways:

• Knowing the cognizance, the observer.

• Knowing whatever is happening right now.

We can practice this in any practice that we are following. And even if we’re not specifically or intentionally practicing [any particular so-called Buddhist practice], you could be doing this — and I would encourage you to do this — right now, as you are listening to this. Just know whatever is happening for you right now.

Action/conduct

Now, in terms of action, we have used terms like “spontaneous action”, “uncontrived” and “unfabricated,” but we haven’t yet talked about what this might mean in practice. Put simply, if we are able to maintain the view in all that we do, then all of our action becomes nondual action. All lifestyles are acceptable. The nondual path is very inclusive. Of course, feminism and racial equity, yes — but so much more than this.

Nonduality in ancient India

Now nondual view, of course, involves going beyond everyday dualities such as left and right, one or many, up or down, before or after, good or bad etc. And even this is already a challenge to our logical and rational way of engaging with the world. And as we’ll see in a moment, our way of working with the world in modernity, our underlying assumptions, are very much based on duality.

But in religious and spiritual traditions, nonduality also means or refers to nondual awareness. It’s also known as “primordial consciousness” or “witness consciousness”, sometimes “primordial natural awareness”. This [nondual awareness] is described as the essence of being, sometimes [as being] centre-less and without dichotomies.

Indian ideas of nondual awareness developed as proto-Samkhya speculations in pre-Buddhist India in the first millennium BCE, with the notion of purusha, which was seen as a witness consciousness or pure consciousness. And in the Indian traditions, the realization of this primordial consciousness — witnessing but disengaged from the entanglements of ordinary mind and samsara — is considered moksha, release from suffering and samsara. And that’s what’s realized through practicing the path.

Nondual awareness in Hinduism and Buddhism

These early ideas of primordial awareness thoroughly influenced both Hindu traditions such as yoga, Advaita Vedanta and Kashmiri Shaivism, as well as Buddhism, which all emerged in close interaction. They all developed philosophical systems to describe the relation between this essence and mundane samsaric reality. So we can find descriptions of nondual consciousness in Hinduism with words like purusha, turiya, and sahaja. And also in Buddhism, with terms like luminous mind, emptiness, parinispanna, nature of mind, and rigpa. But there are important differences between them.

So it’s important to realize when we’re hearing unfamiliar words like “nondual awareness” or “primordial awareness”, that these can mean very different things in different traditions. And we certainly shouldn’t assume that our everyday understanding of these words is the same as the Buddhist understanding. And this is particularly important now that teachings like Dzogchen and Mahamudra are available on Amazon. It’s very easy to misunderstand these profound Buddhist teachings and practices.

(c) The importance of the view

I’d like to talk a little more about the view. We’ve already said in previous weeks that the view is foundational, because the very purpose of our meditation is to familiarize ourselves with the right view — the view-less view of the Middle Way — and our action is only right action when it is informed by the right view. Rinpoche has talked about how view is key to the authentic transmission of Dharma in the West. When he was teaching Madhyamaka in 1996, he said:

In Buddhism, the view is essential for both theory and practice. All the various Buddhist schools and paths have been established based on the right view, and the result of the Buddhist path – enlightenment – is none other than the complete understanding or realization of the view. The view is indispensable for all kinds of Buddhist practice, from the simple and seemingly mundane acts of a Theravadin monk shaving his head and not eating after midday, to the Mahayana practitioner abandoning meat, offering butterlamps and circumambulating, to more complicated and exotic paths such as building monasteries or practicing kundalini yoga. The view not only gives us the reason to practice; it is also the result we seek to attain through practice. Furthermore, the view is also a safety railing that prevents us from going astray on the path. Without the view, the whole aim and purpose of Buddhism is lost.

Now that Buddhism is taking root in the West, I feel it is important for at least some of us to pay attention to the study of the view and how it is to be established. Unfortunately, our human tendency is to be much more attracted to the methods of doing something, rather than why we are doing it. The study of the view appears to be very dry, boring and long-winded, whereas anyone can just buy a cushion, sit on it, and after a few minutes feel satisfied that they have sat and meditated.

[. . . ] Without the view, the whole purpose of Buddhism is lost. It is then no longer Buddhism – a path to enlightenment – but merely a method for temporal healing. So, even for the sake of insurance, at least some of us should pay some attention to establishing the view.

Wrong views

I’d like to talk a little bit about this. Much of the Madhyamaka is about how the idea of nonduality is to be correctly understood. And later Buddhists schools critiqued the ideas of non-Buddhists, of course, but even the earlier Buddhist philosophical schools. It’s a little like a doctor having a wrong view about what’s causing an illness. If you have an incorrect diagnosis, that’s going to lead to an incorrect course of treatment, which would mean the illness would not be cured, and the patient would not be healed. So in philosophy, just as in medicine, we need our view to be correct.

As Rinpoche said, sometimes people think the study of Madhyamaka is dry and boring and academic, and we get more excited about meditation and compassion. But without the right view, our whole path becomes as useless as trying to treat a disease with the wrong medicine. Now, sometimes this language of nonduality can feel very abstract. Especially if we haven’t yet had the opportunity to familiarize ourselves much with the nondual view through our practice, we can easily misunderstand that. And it may not be clear why this view is different from the view we have in our ordinary lives. And part of the challenge of understanding a nondual view is that we’re doing it from within a language and within a culture that is very dualistic. And we may not even realize the extent to which is the case.

The foundation of Western thought is dualistic

So I want to look a little at some of the foundational ideas that underpin Western thought, including our ethics and rationality, and therefore, our economic and political systems such as capitalism and democracy. And even though, of course, we have non-Western traditions alive and well in the world, the influence of globalization, especially global capitalism, is such that these Western ideas have now spread throughout the world. Many CEOs, leaders, practical men and women might not describe their political or leadership principles in terms of this philosophy, this background to Western thought, but it’s there nevertheless.

And it’s also very important for us to understand this as Buddhist practitioners. Of course, especially if we come from Western countries and cultures where this is the default view. But as we just said, these ideas are now to be found everywhere in the world, in the modern, globalized world, even in countries that would not consider themselves Western. So if we don’t understand how our view has this background, we can easily distort our understanding of Buddhism. We might inadvertently turn the nondual path into something dualistic, which would not only affect our approach to ethics and behaviour in the world, but also our meditation practice, our understanding of self, mind and this awareness or cognizance we’ve been talking about. So I’d like to talk a little about some of these backgrounds or foundations to Western thought.

(2) Nonduality and the modern world

(a) What is right and wrong? Abrahamic religions and dualistic ethics

The Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam

Let’s start with ethics. Or in this case, the Abrahamic, religious traditions. Western morality and ethics are about asking and answering the question about what is [good]? What is right and wrong behaviour. And this is based in the west on the teachings of the three main Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. And they all accept the tradition that God revealed himself to the patriarch Abraham. They’re all monotheistic. They all conceive of God as a transcendent creator. And also as the source of moral law.

The individual, God and the universe are highly separate from one another. The Abrahamic religions believe in a judging, paternal, fully external God, to which the individual and nature are subordinate. And one seeks salvation and transcendence not by contemplating the natural world or via philosophical speculation, but by seeking to please God, such as obedience with God’s wishes or his law. And they see divine revelation as outside self or nature or custom.

So all three are clearly dualistic. God is quite separate from the individual. Heaven is quite separate from Hell. Good is very different from bad. Right very different from wrong. One either obeys God’s wishes and his law, or one doesn’t. This is perhaps most famously told in the Christian story of Adam and Eve, and the doctrines of the fall of man and original sin. These are important beliefs in Christianity, although perhaps not so much in Judaism and Islam.

The story of Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve were the first man and woman. And they’re central to the Christian belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. And in the book of Genesis of the Hebrew Bible, in the first five chapters, there are two creation narratives with two distinct perspectives. In the first, Adam and Eve are not named. Instead, God created humankind in God’s image and instructed them to multiply and be stewards over everything that God had made.

In the second narrative, however, God fashions Adam from dust and places him in the Garden of Eden. Adam is told he can eat freely of all the trees in the garden, except for the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Subsequently, Eve is created from one of Adam’s ribs to be his companion. They are innocent and unembarrassed about their nakedness. However, a serpent convinces Eve to eat fruit from the forbidden tree, and she gives some of the fruit to Adam, and these acts give them additional knowledge. It gives them the ability to conjure negative and destructive concepts such as shame and evil. God later curses the serpent and the ground. He prophetically tells the woman and the man, what will be the consequences of their sin of disobeying God, then he banishes them from the Garden of Eden.

Unlike Christians, Buddhists do not believe in original sin and evil

I’m not going to attempt to cover 2000 years of commentary on this ancient story, but suffice it to say that we have ended up with a Christian doctrine of original sin, namely, that humans inherited a tainted nature and a proclivity to sin through the fact of birth. But this is not a belief that is shared by Buddhism. There is no concept of original sin or evil in Buddhism. Buddhist ethics are founded on the idea that the root cause of people saying and doing harmful things is not a sinful disposition, but ignorance and wrong views.

In Buddhism, as we saw in Week 2, you are your own master. The solution, therefore, is to overcome ignorance through establishing and familiarizing yourself with the right view. As the Buddha said, I can only show you the way. You have to do your own work. Whereas in Christianity, only God can forgive. And atonement, which refers to the forgiving and pardoning of sin in general and original sin in particular, happens through the suffering, death and resurrection of Jesus.

Dualistic Abrahamic concepts of good and evil are the basis of Western ethics and society

Now, the influence of Abrahamic concepts of good and evil on Western thought, ethics, politics, legal systems, and society is profound and nearly ubiquitous. And we don’t see it. Remember David Foster Wallace’s story, “This is water”. The fish don’t necessarily know they’re swimming in the water. And also remember john Maynard Keynes, “Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence are usually the slaves of some defunct economist”. And perhaps we could add that they are usually slaves to some prophet or theologian.

So for Western Buddhists in particular, many have come from families or cultures that were originally Christian. And so this influence of Christianity is probably going to be there. And if nothing else, it’s there in the very structure of Western language, in our words, in the way we form concepts. They come with all these connotations, these semantic relationships that link back to these underlying dualities. And as Rinpoche said, even in Buddhist countries like Bhutan, a lot of the school system was put in place by Christian missionaries. So even young Bhutanese people, when they’re growing up with ideas of ethics and morality, those are in many cases more Christian than Buddhist.

So just as a reflection, I think it’s very important for us just to pause and ask, Well, how many of our ideas of good and bad, of right and wrong, are based on some underlying dualistic system, which in turn is based on some Abrahamic understanding? Because I think very often people ask questions about Buddhism coming from this sort of ethical framework. And it really is quite different. As Rinpoche says, people often ask questions like, do Buddhists think it’s right or wrong to eat meat, or to drink alcohol, or things like that? And I think a lot of those questions come from this kind of ethical frame. And it’s just a very different way of thinking from the Buddhist way. So we’ll come back to that.

(b) What is true? Western philosophy and dualistic thought

There is a second major area of difference, namely the way that Western thought is founded on logic and rationality. And in particular, there’s something called the three laws of thought, which are fundamental foundations of philosophy. They are axiomatic rules upon which rational discourse itself is based. These have a long tradition in the history of philosophy and logic, going back certainly as far as ancient Greek philosophy. And generally they’re taken those laws that guide and underlie all thought, all expression, and all discussion in the Western world and now, of course, in the modern, globalized world. So here are the three laws:

(1) The law of identity.

(2) The law of non-contradiction.

(3) The law of excluded middle.

I’m going to talk about them using the words of Bertrand Russell.

(1) The law of identity: ‘Whatever is, is.’

For all a: a = a.

Regarding this law, Aristotle wrote:1Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book IV, Part 4 (translated by W. D. Ross).

First then this at least is obviously true, that the word “be” or “not be” has a definite meaning, so that not everything will be “so and not so”. Again, if “man” has one meaning, let this be “two-footed animal”; by having one meaning I understand this:—if “man” means “X”, then if A is a man “X” will be what “being a man” means for him.

So this is very basic. It’s saying that we need to be able to have fixed ideas of identity to be able to use thought or language at all. Because if this law does not hold, then words and language will collapse. There’ll be no stable system of representation, no stable system of meaning. If what we refer to changes from one moment to the next, then we will no longer be able to talk or think about anything. Thought and language would become completely impossible. I think sometimes we don’t even realize the extent to which this is foundational for us, this idea of identity.

(2) The law of non-contradiction: ’Nothing can both be and not be.’

In other words, two or more contradictory statements cannot both be true in the same sense at the same time:

¬(A∧¬A).

Aristotle said, “one cannot say of something that it is and that it is not in the same respect and at the same time”. He said:2Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book IV, Part 4 (translated by W.D. Ross).

It is impossible, then, that “being a man” should mean precisely not being a man, if “man” not only signifies something about one subject but also has one significance … And it will not be possible to be and not to be the same thing, except in virtue of ambiguity, just as if one whom we call “man”, and others were to call “not-man”; but the point in question is not this, whether the same thing can at the same time be and not be a man in name, but whether it can be in fact.

So this is why contradiction is such a big problem in western thought and it is so central in western logic. As Aristotle points out, it’s not about whether we’re choosing to use the same names for something, but about whether we’re referring to the same underlying reality, in other words, the same facts about the world. As we’ve seen in contemporary politics and the rise of fake news, we see that once agreement on a shared reality starts to break down, any hope of rational discourse falls apart.

(3) The law of excluded middle: ‘Everything must either be or not be.’

A∨¬A.

Here Aristotle said:3Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book IV, Part 7 (translated by W.D. Ross).

But on the other hand there cannot be an intermediate between contradictories, but of one subject we must either affirm or deny any one predicate. This is clear, in the first place, if we define what the true and the false are. To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true; so that he who says of anything that it is, or that it is not, will say either what is true or what is false

This is very foundational to logic. In other words, if there are two opposed and contradictory alternatives, we have to choose one or the other. Let’s take an everyday example, if someone were to ask, Will you marry me? You might be unsure, you might need more time to consider your answer. But there are only two answers. Likewise, if a doctor were to examine an injured person, he might ask is this person dead or alive? Again, there are only two answers.

According to the law of excluded middle, this must always be the case for any coherent rational conversation. Now, of course, we can think of examples where this does not apply. For example, if somebody were to say, Are you happy or sad? The answer is often going to be something in between, or a complex mix of positive and negative emotions. But this doesn’t disprove the law of excluded middle. Rather, it shows that the choices in question are not clearly defined. We could also say that we’re asking the wrong question. We’re trying to impose a dualistic yes or no choice on concepts that are much more complicated.

As Buddhists, we’re going to run into quite some problems with this third law, because instead of excluding the middle, we embrace the middle. Our very path is the Middle Way.

(c) Towards a more nondual future?

Duality is foundational to Western thought

So [this is our] context. Duality is foundational to Western logic, Western rationality, Western thought, and now global modern thought. So if we’re going to engage in the nondual path, we’re going to be coming up against some fundamental contradictions. And we may not be fully aware of this. Writing at the end of the 19th century, the philosopher James Welton wrote:

The laws of thought are those fundamental necessary formal and a priori mental laws in agreement with which all valid thought must be carried on. [. . . ] They’re necessary because no one ever does, or can conceive them reversed, or really violate them. Because nobody ever accepts a contradiction, which presents itself to his mind as such.

Buddhism is going to present us with a lot of contradictions. Now, in contemporary philosophy, there are developments that challenge classic dualistic logic, such as intuitionistic logic, dialetheism and fuzzy logic. And now with the rapid emergence of artificial intelligence, we’re grappling with new ways of thinking about rationality, decision making, and representation of knowledge.

Artificial intelligence and the rise of nonduality

Personally, I have a suspicion that the rise of artificial intelligence is going to lead to a significant challenge to the three laws of thought. And it’s going to result in the emergence of a nondual way of thinking in the West. Much like at the end of the 19th century, classical physics was challenged, and then extended and superseded by quantum physics and relativity. Of course, classical physics is still useful for solving many everyday problems. And likewise, we shouldn’t expect that everyday language logic and rationality will suddenly become useless. Far from it.

But my suspicion is that in the same way that physicists now realize they can’t explore the far reaches of the universe, or the interior of the atom using the tools and language of classical physics. I predict that pretty soon, sometime in the next couple of decades, we’re going to come to see that we cannot rely solely on the dualistic foundations of modern thought.

Now as a Buddhist, I find that very encouraging. Because once nonduality becomes more prevalent, more commonplace, I think there’s going to be much more interest in nondual systems of thought and practice, especially the Middle Way of Buddhism, and I think that’s going to result in quite some renaissance of the Middle Way. So perhaps if we were to meet again, in 20, or 30, or 40 years, things will be quite different. Let’s see. I’ll make a bold prediction. Let’s see how accurate I am.

(3) Nonduality and the Buddhist path

(a) Poison is medicine

Higher and lower paths

Let’s turn now to the Buddhist path, again [using the framework of] view, meditation, action and result:

• View: the view is how we see the world, the reality of self, others, the world itself. What is the truth that we’re establishing, the nature of self?

• Meditation: how are we going to familiarize ourselves with this view, so that it becomes internalized and embodied?

• Action/conduct: how to conduct our activities in the world?

• Result: and the result, the state of awakening, enlightenment liberation.

It’s said there are 84,000 paths in Buddhism, and all lead to awakening. But as humans, we love hierarchies. We want to know what is good and bad, what is high and low. We want the best, the highest, the fastest, the easiest, the most powerful. If we were able to buy spiritual paths online, we would probably also want the one with the best price. But actually, if we’re talking about [how we might define a] “higher” path in Buddhism, we will talk about the extent to which it is dualistic, as opposed to nondual. And ironically, the highest path is the one that cares the least about the distinctions of high and low.

Rinpoche talks about how poison is medicine. The idea that the closer the problem is to the solution, the more nondual or the higher the path. [Whereas] the greater the separation, the more dualistic, then the path has much more contrast, it’s much easier to understand and to follow, and we might term it a lower path. This doesn’t mean it’s less effective. It doesn’t mean it leads us anywhere different. So higher and lower shouldn’t be understood in that sense.

And in fact, the nondual path might superficially look easier, because there’s seemingly less to do. But unless you have very great ability, the challenge is that you might just end up practicing your ordinary samsaric ways of thinking and ways of being in the world. So if we think about the highest or the best path, really it’s very individual. The best is what is most beneficial to you. It’s the best medicine to treat your own individual sickness.

Challenge and support

And as we progress along the path, what is best for us will change, which is part of the reason, especially in Tibetan Buddhism, that the path is taught as a graduated path. So when we talk about 84,000 [paths and] teachings, it’s a bit like [learning to become] a surfer. As a beginning surfer, we want to learn with relatively small waves, because if we try and take on a big wave, it’s just going to knock us straight off our board. But for an expert surfer, big waves are not just fun, they’re also necessary to provide the challenge for us to continue to progress with our path, with our development, with our growth. This is something general we’ll see not just in Buddhism, but throughout coaching and throughout human development. We need the right balance of challenge and support. We need a middle way, a middle path. And it’s no different in Buddhism.

So yes, maybe just knowing what’s happening right now is the easiest thing to do in the world. As we said in previous weeks, we have this cognizance. We’re knowing things all the time anyway. So what is happening for you right now?

[30 seconds]

Just knowing this is so hard, because it’s so easy to get caught almost immediately in thoughts and narratives take us away to the next thing, and awareness is left behind.

[30 seconds]

So we might perhaps notice a sound, but instead of just knowing it, we start some kind of narrative. “Oh, that sound is the wind picking up, maybe a storm is coming. I should remember to close the windows”. We no longer know what’s happening as it is happening. We’re caught in the thoughts rather than knowing the thoughts.

So this easiest practice is actually the hardest. Thirty minutes can go by, and you can be sitting on your cushion but you didn’t practice for more than a split second. Your mind was wandering, and you didn’t even know it. This doesn’t mean we can’t do this. Of course we can. But we do need to practice. And unless you’re a practitioner of a very particular ability, your teacher will probably want to supplement these practices with something else. Something more solid, something more dualistic. Not because these [more dualistic] practices are worse or lower, but because we’re still beginning as surfers. We still need something that we can learn to practice with.

Poison is medicine

So in his book, “Poison is Medicine”, Rinpoche said:

The Vajrayana is the best thing that ever happened on this planet. Not only does it train us to think outside samsara’s box, it shows us how to be inside and outside the box at the same time. And, although the tumultuous ocean of jealousy, anger, pride, doubt, greed and delusion that fills our minds can feel extremely daunting, the Vajrayana tells us it needn’t be. The antidote to all that poison is not outside us, but within. We already have exactly the right dose. Not a single drop is missing. Nothing needs improving, upgrading, customizing, or adapting. Our innate wisdom is the antidote we seek. It is perfectly intact and available for immediate use – as it always has been. Is this idea too hard for you to chew? If it isn’t, why not have a go at tracking down your own innate wisdom. How? By following wisdom’s footprints, which are your emotions.

The essence of the Vajrayana’s message is that poison is medicine just as it is, with nothing added and nothing taken away. I hope and pray that none of you ever lose your enthusiasm for and curiosity about this glorious, brilliant and incomparable path.

Yes, Vajrayana is the nondual path. It does start with that [nonduality] as the basis for the practice. But it’s not easy. Hence, the poison is the medicine. Not just in the sense that we use the emotions as a way of healing the sickness, so we use the poison itself as medicine. But if we’re not careful, the medicine also can become a poison. We can think we’re treating and healing ourselves. But all we’re doing is just continuing with our everyday way of being in the world. And it does get back to this point about the foundations of Western thought. Rinpoche said:

For centuries, Christian missionaries travelled to the East to spread the gospel and convert the natives. Asians have therefore never had to seek out the Christian teachings. For westerners it was the other way around. I have heard some very touching stories about the higgledy-piggledy routes Buddhism took to the UK, America and Europe – especially about the hippies who followed The Beatles to India, accidentally bumped into Buddhism, tuned into transcendental meditation and took up yoga. But few of those who took an interest in Buddhism at that time were specifically seeking enlightenment and so they did almost no research or fact-checking. All of which made Buddhadharma’s centuries-long journey to the West haphazard, at best. Yet, in spite of its chaotic introduction, the results of having the Buddhist teachings in Europe, America and Australia have generally been good. The only real drawback is that quite a number of new Buddhists have been left with some quite hard-to-shake misconceptions and deeply rooted habitual patterns.

Easy is difficult, difficult is easy

We have talked about the highest view, just knowing the cognizance. HH Dudjom Rinpoche, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s grandfather said, “Let this life is spent in this state of uninhibited naked ease.” Literally we can laze around all day and do nothing. It’s only [about our] being — our intention, our attitude, and yet that alone could be perfect practice. Of course, that sounds very attractive. Who doesn’t want to think they can lie in a hammock and have a cocktail and do their practice. But how many of us can actually do that? How many of us can lie in a hammock and drink a cocktail and actually stay with what is happening right now? Of course, if we can, it’s wonderful. That can be our practice.

But for many of us, it is as Rinpoche says, like the charnel ground and the forest glade. We have talked in previous weeks about how for many of us, it’s much safer, much better, as the Buddha said, to take ourselves out of the distraction, the noise, the confusion, the complexity of our busy lives, and find a space of peace and silence. Whether it’s going to an actual forest blade, or creating these moments of forest glade in our lives. secluding ourselves, retreating ourselves. Whether it’s to space in our homes, maybe going on a retreat, maybe even just turning off our phones and giving ourselves a few moments of time just for ourselves.

And, oddly, the [seemingly] hardest [and most restrictive] environments, the ones with the greatest of constraint and conformity, may actually be the easiest for our practice. Because while the highest might be to practice in a channel ground with all this confusion and noise and distraction — yes, that’s wonderful if we can practice there. But if we can’t, it’s not going to help us at all. So more constraints are [very often] better. Retreat boundaries, shrine rooms, mountain hermitages.

Misconceptions about the practice

And also, we’ve talked already about some of these widespread misconceptions that Rinpoche mentioned, namely, what is vipassana. We’ve talked about how actually the practice of vipassana is seeing the truth. It doesn’t even need to be sitting. You could be doing vipassana while chopping onions or arranging flowers. It doesn’t even need to be something meditative. It could be reading a book with the aim to deconstruct wrong views. Whereas in the West, as we’ve seen, it’s become about calm, stillness, presence, relieving our stress and anxiety.

Indeed, it has become little more than shamatha or calm abiding. And the aim is no longer about seeing the truth. It’s much more about managing our mind, about less stress, less anxiety, less depression, more self compassion, more positive emotions, increasing our ability to be focused, all so that we can be happier and more successful in our worthy endeavours. None of this is bad. Far from it. Buddhism welcomes this. Buddhism by no means want us to be stressed or unhappy or unsuccessful. It’s just that none of these things are the aim of the Buddhist path.

The problem for new Buddhists might be that they genuinely want to learn more about Buddhism, they might follow a vipassana course, or download a meditation app, and then think “This is it”.

Doing and being

Part of the problem is that in the modern world, we’re very used to judging or classifying an activity by what people are doing, rather than their state of being — their intention, their attitude, their state of mind — while they’re doing whatever it is they’re doing. We’ll talk about this more next week.

So for example, you could have two people sitting beside each other, both in perfect meditation posture, and one could be mindfully watching the breath and contemplating impermanence, while the person sitting next to him could be fantasizing about stock portfolios, how they’re going to make more money, etc. And we might look at them and conclude they’re both practicing meditation, we have no idea. Especially if we’re seeing them both beside each other in a Buddhist retreat centre. If they are both carrying malas with Buddhist books beside them, and maybe they’ve got a picture of HH The Dalai Lama as the wallpaper on their phone. We might even have experienced something like this in our own practice.

So as we think about nonduality, much of what makes it hard is that it isn’t necessarily going to be visible in our behaviours at all. It is so much in our view, in our intention, in our attitude. I’d like to share a couple of Zen stories, as the Zen tradition very much loves and reveres nonduality also. And these stories are wonderful, like all Zen koans, as a way of challenging our ordinary dualistic thinking, and perhaps shaking us a little bit out of the sleep of our habitual way of understanding the world.

So the first one is from the book “The Gateless Gate”:

#26: Two Monks Roll Up the Screen

Hogen of Seiryo monastery was about to lecture before dinner when he noticed that the bamboo screen lowered for meditation had not been rolled up. He pointed to it. Two monks arose from the audience and rolled it up.

Hogen, observing the physical moment, said: “The state of the first monk is good, not that of the other.”

The second is also from “The Gateless Gate:

#11: Joshu Examines a Monk in Meditation

Joshu went to a place where a monk had retired to meditate and asked him: “What is, is what?”

The monk raised his fist.

Joshu replied: “Ships cannot remain where the water is too shallow.” And he left.

A few days later Joshu went again to visit the monk and asked the same question.

The monk answered the same way.

Joshu said: “Well given, well taken, well killed, well saved.” And he bowed to the monk.

So as you can see, nonduality is far from our ordinary way of proceeding in the world. So with that, let’s take our 10 minute break and I will see you back here in 10 minutes.

[END OF PART 1]

Part 2

(3) Nonduality and the Buddhist path (continued)

(b) View

Direct and indirect teachings

Returning to our topic we’ve said the view in Buddhism is nondual, but that’s not necessarily the way it’s presented to beginners. Rinpoche told the story of a professor with a stuffed teddy bear. He said how if there’s a professor walking with a small child by the edge of a cliff for the child risks falling from the cliff, [the professor is] not going to give some high level lecture about gravity and so forth. He’s going to entice the child away from the edge of the cliff with the stuffed teddy bear.

His interest at that point is one of helping — skillful means — not necessarily in the truth or the correct view. He obviously doesn’t want to do something that’s incorrect or unhelpful. We should take that same attitude to our understanding of the teachings. The Buddha taught the truth very directly in certain teachings, in a very raw and unvarnished way. But it’s hard for many of us to understand this, and put it into practice in its raw state. And so out of his great compassion, he taught the truth in many other ways also. So there’s something suitable for practitioners at any stage of their journey.

And as we said, in the lower views samsara is seen as very different from nirvana, good is seen as different from bad, there are clear contrasts and distinctions, and [as a result] it’s much easier to understand. And this is essential for us when we’re beginners, because when we’re first learning a new vocabulary, a new set of concepts, we can’t yet distinguish subtle differences. It’s like a child first learning language or first learning a subject at school. We’re just trying to build a basic map of the territory.

A higher view is more nondual, and has fewer distinctions. Rinpoche expresses the [nondual] view very simply and beautifully when he says it’s there, and it’s not there. So that’s actually a very high way of saying it, and we’ll come back to try and unpack that. And you can immediately see that goes against the three laws of thought we were talking about just before the break. There’s paradox. There’s seeming contradiction. [It’s there — and — it’s not there?] It seems quite illogical according to the Western laws of thought.

The nondual view as expressed in the Heart Sutra

I’d like to turn to the Heart Sutra, which is said to be the single most commonly recited, copied, and studied scripture in East Asian Buddhism. I’m going to read it, and I encourage you to listen to the words. What does it actually mean?

Thus have I heard

Once the Blessed One was dwelling in Rajagriha at Vulture Peak mountain, together with a great gathering of the sangha of monks and a great gathering of the sangha of bodhisattvas. At that time the Blessed One entered the samadhi that expresses the dharma called profound illumination, and at the same time noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, while practicing the profound prajñaparamita, saw in this way: he saw the five skandhas to be empty of nature.

As you may recall, that’s the various elements of the self. The Heart Sutra continues:

Then, through the power of the Buddha, venerable Shariputra said to noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva,

“How should a son or daughter of noble family train, who wishes to practice the profound prajñaparamita?”

Addressed in this way, noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva said to venerable Shariputra,

“O, Shariputra, a son or daughter of noble family who wishes to practice the profound prajñaparamita should see in this way: seeing the five skandhas to be empty of nature.

Form is emptiness; emptiness also is form. Emptiness is no other than form; form is no other than emptiness.

In the same way, feeling, perception, formation, and consciousness are emptiness. Thus, Shariputra, all dharmas are emptiness. There are no characteristics. There is no birth and no cessation. There is no impurity and no purity. There is no decrease and no increase.

Therefore, Shariputra, in emptiness, there is no form, no feeling, no perception, no formation, no consciousness; no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no appearance, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no dharmas; no eye dhatu up to no mind dhatu, no dhatu of dharmas, no mind consciousness dhatu; no ignorance, no end of ignorance up to no old age and death, no end of old age and death; no suffering, no origin of suffering, no cessation of suffering, no path, no wisdom, no attainment, and no non-attainment.

Therefore, Shariputra, since the bodhisattvas have no attainment, they abide by means of prajñaparamita. Since there is no obscuration of mind, there is no fear. They transcend falsity and attain complete nirvana. All the buddhas of the three times, by means of prajñaparamita, fully awaken to unsurpassable, true, complete enlightenment.

Therefore, the great mantra of prajñaparamita, the mantra of great insight, the unsurpassed mantra, the unequalled mantra, the mantra that calms all suffering, should be known as truth, since there is no deception. The prajñaparamita mantra is said in this way:

OM GATE GATE PĀRAGATE PĀRASAMGATE BODHI SVĀHĀ

Thus, Shariputra, the bodhisattva mahasattva should train in the profound prajñaparamita.”

Then the Blessed One arose from that samadhi and praised noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, saying,

“Good, good, O son of noble family; thus it is, O son of noble family, thus it is. One should practice the profound prajñaparamita just as you have taught and all the tathagatas will rejoice.”

When the Blessed One had said this, venerable Shariputra and noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, that whole assembly and the world with its gods, humans, asuras, and gandharvas rejoiced and praised the words of the Blessed One.

The Heart Sutra does not make any sense in terms of our conventional reality

So that’s the core of the Heart Sutra. And for many of us, if you’ve come across this before, maybe it’ll be very familiar, maybe even will feel like an old friend. Let’s just pause and look at the words for a moment.

There are no characteristics. There is no birth and no cessation. There is no impurity and no purity. There is no decrease and no increase.

For most of us, that’s very far from our current experience of reality. There is birth and cessation with every moment of thought and emotion as our minds keep drifting. And most certainly, our experience of the world can differentiate characteristics of good and bad, right and wrong, profit and loss, pure and impure. We couldn’t even make it through a single day without these distinctions. We couldn’t even make it through breakfast. If they were no characteristics, how would we know to eat the food on our plate rather than the plate itself? Or our fork? Or our chopsticks? How would we even know to look for food in the fridge rather than the garbage?

You see the point. Dualistic distinctions are what enable us to navigate our world. And if you’ve ever spent time with a baby, you realize that it’s very important for babies to learn distinctions to survive. Fire will burn. A sharp knife will cut. An aggressive dog can bite you. Yes, eventually, we’re going to have to undo all these dualistic distinctions once we start to practice the Mahayana path, the Heart Sutra. But if we don’t teach these things to our children, we’re very negligent parents and our babies won’t end up becoming adults.

No ignorance, no end of ignorance up to no old age and death, no end of old age and death; no suffering, no origin of suffering, no cessation of suffering, no path, no wisdom, no attainment, and no non-attainment.

So here we have the total deconstruction of the path and even the result. And you would be forgiven for asking, Why would I bother to follow this path? Why on earth follow a path where it says there is no end of ignorance, no cessation of suffering and no attainment? What kind of path is this? It says there’s not even a goal that’s going to come from following this path.

The Heart Sutra should shock us

The Buddhist translator Karl Brunnhölzl translated the Heart Sutra and wrote a commentary, and he gave his book the title, “The Heart Attack Sutra”. [He writes in the introduction]:

There are accounts in several of the larger prajñaparamita sutras about people being present in the audience who had already attained certain advanced levels of spiritual development or insight that liberated them from samsaric existence and suffering. These people, who are called “arhats” in Buddhism, were listening to the Buddha speaking about emptiness and then had different reactions. Some thought, “This is crazy, let’s go” and left. Others stayed, but some of them had heart attacks, vomited blood, and died. It seems they didn’t leave in time. These arhats were so shocked by what they were hearing that they died on the spot That’s why somebody suggested recently that we could call the Heart Sutra the Heart Attack Sutra.

Rinpoche commented on this story [of the arhats having heart attacks], and he said:

Petty-minded people like us might use these stories to boost our ego because we follow the Mahayana, but this would be a mistake, as the story is actually praising the shravakas! Their shock means that at least they understand something, whereas we are so dumb that it does not touch us.

That’s really important. Yes, we can hear these words, but they can bounce right off us and not penetrate us at all. [So are we really ready to hear the teachings on emptiness? Will they be of any use to us?]

How emptiness should be taught to three different kinds of people

When Rinpoche was teaching Madhyamaka and going through the commentary by Chandrakirti, the Madhyamakavatara, there is a section at the beginning of the sixth chapter about the people to whom we should teach this nondual view. And there are three kinds of people that we should consider.

(1) Someone with an established philosophy

The first is someone who already has an established philosophy such as Hinduism or Buddhism. As Rinpoche said, it’s much easier to teach a hardline Muslim or Christian, because at least they have a view and we can debate them. Whereas it’s very difficult to teach somebody New Age because they are like honey, they paste things from here and there. We don’t know what they’re talking about, or where we should try and direct our arguments. So if we’ve got a person [who has a] philosophy, we will teach the Madhyamaka with all of [its logical reasoning and] arguments and we will aim to defeat their own views and set them up with the right view, which they can then practice.

(2) Someone completely new

The second kind of person is a person who’s completely new, with no philosophical background. Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo says such a person does have to have one quality, namely shame and embarrassment. And he says you will find this easily. As long as a person has ego, they have shame and embarrassment. For someone like this with no religious or philosophical background, we begin with mind training. We teach them things like the faults of samsara, the effects of karma, the preciousness of the human body, shamatha meditation, the different meditations on bodhichitta. We teach a gradual path, and only then do we introduce the Madhyamaka. Because according to the Mahayana sutras if a person does not have a good foundation of mind training and practice, it’s considered a violation of the bodhisattva vow to teach them Madhyamaka, as it could destroy them. In the Mulamadhyamakakarika, Nagarjuna said that teaching emptiness directly to someone not qualified is like someone with no experience holding a poisonous snake.

(3) Someone who experiences great joy upon hearing of emptiness

The third kind of person is explained in verses four and five:

6:4

Certain simple, ordinary people,

When they hear of emptiness, will feel

A joy that leaps and surges in their hearts.

Their eyes will fill with tears, the hairs upon their skin stand up.

6:5

Such people are the vessels for the teaching;

They have the seed of wisdom, perfect buddhahood.

The final truth should be revealed to them,

In whom ensuing qualities will come to birth.

As Rinpoche said, you can teach this kind of listener directly. You do not need to convince them with logic, you don’t necessarily need to give them all the foundational teachings. But very few of us, I think, have this kind of reaction when we hear emptiness.

The horse and the donkey

So maybe it would be best for us to do all of the above, yes, aspire to understand and practice nonduality directly. But at the same time, as Rinpoche says, if we’re riding a horse, we should always bring a donkey as well, so that if we fall from the horse, at least we have a way of continuing our journey. So for us, this means we should continue to study [nonduality] and challenge our own dualistic views. Since although we may not be philosophers, we do have a philosophy. We’re all fish swimming in water.

And secondly, we should all practice the gradual path. We should always invest in cultivating wisdom, compassion, and mindfulness using all the practices we may have been taught. And despite them being more gradual, seemingly more dualistic, we should never despise them. And don’t forget, we can always apply the nondual view, this mere cognizance, no matter what it is that we’re doing.

(c) The two truths

Relative truth and ultimate truth

So let’s talk a little more about the two truths. And remember we’re working within this dualistic Abrahamic culture. It can a little hard perhaps to understand nonduality from this place. Be openminded if you can. And if you can’t, then at least try to be aware of the potential effect of language and the underlying thoughts.

Rinpoche gave the example of taking some kind of hallucinogenic substance and experiencing that you have a tail. And in the Madhyamaka, we talk about two truths – relative truth and ultimate truth:

• Relative truth is the fact that you experience that you have a tail, subjectively.

• Ultimate truth is that you have no tail in reality.

And remember, in previous weeks, we talked about showing a photograph to the Me’en people in Ethiopia. Now, ultimately, of course, there’s no photo, there’s just something printed on a piece of paper [and even “piece of paper” is a phenomenon that probably does not exist for the Me’en people]. Nevertheless, in our relative truth there is a photograph, whereas in their relative truth there is no photograph. So relative truths are very subjective. They’re very individual. They’re very impacted by culture.

[If you have taken this substance], the relative truth [for you] is that there is a tail in your experience. It’s what’s in the mind of the person who has taken this substance. They feel it, it bothers them. And Buddhists don’t deny this relative truth at all. They very much accept that we all have subjective experiences.

But the ultimate truth is there is no tail outside our subjective experience. There is no objectively or independently existing tail. In fact, more properly, the ultimate truth isn’t even saying that there is no tail. We don’t even speak of the tail. The tail neither exists nor doesn’t exist. There’s no need to deconstruct it, because there is none there in reality. Only someone who’s taken the substance would even talk about the tail. They’ll say, Yes, I took the substance I experience the tail. As the effects of the substance wanes, the effect of the tail experience slowly fades.

But why a tail, right? There’s nothing which would suggest we wouldn’t experience having wings or having scaly skin. None of these subjective experiences are there in reality. It’s just what’s brought up with our personal causes and conditions. So as Rinpoche says, this is the paradox. We have these two truths, seemingly it’s there and it’s not there. And all phenomena like this.

Relative truth is conventional truth

And it’s not just something that happens at the individual level. It’s also social and conventional. Because our reality is shared through language, through culture. It’s based on characteristics like how things persist over time, whether they function and actually do things, and how many people agree [that these things exist]. What is the consensus? For example, you could say, within the US today, there is a shared relative truth that we should have a President rather than, for example, a king or a dictator. But there’s very much not a shared relative truth about whether Trump was a good President, or even if Biden fairly won the election.

And as Rinpoche said, if 51% of a population were to take the substance, then the very nature of our democracy would change. There’s a nice story told by Kahlil Gabran called “The Wise King”:

Once there ruled in the distant city of Wirani a king who was both mighty and wise. And he was feared for his might and loved for his wisdom.

Now, in the heart of that city was a well, whose water was cool and crystalline, from which all the inhabitants drank, even the king and his courtiers; for there was no other well.

One night when all were asleep, a witch entered the city, and poured seven drops of strange liquid into the well, and said, “From this hour he who drinks this water shall become mad.”

Next morning all the inhabitants, save the king and his lord chamberlain, drank from the well and became mad, even as the witch had foretold.

And during that day the people in the narrow streets and in the market places did naught but whisper to one another, “The king is mad. Our king and his lord chamberlain have lost their reason. Surely we cannot be ruled by a mad king. We must dethrone him.”

That evening the king ordered a golden goblet to be filled from the well. And when it was brought to him he drank deeply, and gave it to his lord chamberlain to drink.

And there was great rejoicing in that distant city of Wirani, because its king and its lord chamberlain had regained their reason.

I’m not suggesting that we should all go mad with the belief in self. But just to say, as Rinpoche said in the past, perhaps if somebody is struggling with the idea that they have a non-existent tail, rather than argue with them, maybe you should say, Okay, I understand, let’s get you a better tailor, maybe we can find a way of adjusting your suit to hide the tail. Back to this notion of skillful means, the teddy bear.

(d) Nonduality in the Vajracchedika Sutra – dreams and illusions

Phenomena are like a dream or an illusion

Now, in the Prajñaparamita Sutras, and Rinpoche taught specifically on the Vajracchedika Sutra, also known as the Diamond Cutter Sutra, we say that:

All conditioned phenomena

Are like a dream, an illusion, a bubble, a shadow,

Like dew or a flash of lightning;

Thus, we shall perceive them.

And this applies to all phenomena. A strawberry, you, me, Buddha, rebirth, all conditioned phenomena. Democracy is like a bubble. Likewise free speech, shopping, parenting, insurance policies, all of it. But when we say it’s like a dream, it doesn’t mean it’s random or disordered. In the dream, you fall from a cliff and you panic, and there’s good reason. You know what’s going to happen. In the dream, you get excited, you get scared, you get horny. All this happens as relative truth. And it required the right causes and conditions to come together. If you want to see an oasis, you need to go to an endless desert, you’re not going to see it on Bondi Beach.

Now, [because phenomena are] like a dream or like an illusion, hence [we can use] the language of It’s there and it’s not there. Because illusions they’re not there in reality, but we experience them subjectively. An illusion has this paradoxical nature. It’s nice. And it’s very different from the classical Western logic of things either being there or not there. With just the subtle shift from the OR to the AND, we go from excluding the middle to allowing the middle, and so we now have the Middle Way.

Rinpoche described this using the Tibetan word zungjuk, which means union. The word seems very comprehensible. We can use this language [even if] it may not yet really touch us emotionally, may not yet really be disrupting our normal worldview. And I think often we misunderstand the word “middle” to imply some kind of average or compromise. But that’s not what it means in Buddhism. It means going beyond extremes. So I actually really like the word “union”, and I love Rinpoche’s way of saying “there and not there”. Because you realize it’s not some kind of compromise. It’s the union of seeming opposites. It’s paradox.

Examples of illusion

Now I’d like to spend a moment on this idea of illusion or virtual reality, because we might think we’re just using some example that actually is not relevant to how our minds function. But that’s not actually what we know from modern physiology, modern cognitive science at all.

As the cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene writes in his book “Consciousness and the Brain”:

We never see the world as our retina sees it. In fact, it would be a pretty horrible sight: a highly distorted set of light and dark pixels, blown up toward the centre of the retina, masked by blood vessels, with a massive hole at the location of the “blind spot” where cables leave for the brain; the image would constantly blur and change as our gaze moved around. What we see, instead, is a three-dimensional scene, corrected for retinal defects, mended at the blind spot, stabilized for our eye and head movements, and massively reinterpreted based on our previous experience of similar visual scenes. All these operations unfold unconsciously — although many of them are so complicated that they resist computer modelling. For instance, our visual system detects the presence of shadows in the image and removes them. At a glance, our brain unconsciously infers the sources of lights and deduces the shape, opacity, reflectance, and luminance of the objects.

So we might think that [referring to our experienced phenomena as “illusion”] is just a Buddhist example, but far from it. And actually, I would say this is one of the things that’s quite exciting about modern science, because the more we learn about how our brains function, the more we realize everything in our experience is actually a virtual reality. It’s a construction. It is in a very real way an illusion.

Even the eye itself, we used to think in the Middle Ages that light came in through the eyes and the lens and somehow landed on cells at the back of the eye and went to the brain. But now we realize that something like 90% of the optical nerves that go to the eye are actually taking information to the eye from the brain, rather than the other way around. It’s not a simple one-way process, like a funnel, where information is funnelled into the brain.

Actually, the eye is being presented all the time with predictions and hypotheses by the brain of what it thinks should be happening. And the eye is actually doing a lot of work just to test these predictions and decide whether or not they make sense. So we have a top-down flow of information, models, and predictions [being generated by the brain]. And a bottom-up flow of information [drawn from sensory] reality. And [these two streams of information are then combined in a way that] allows us to make sense of the world.

Some visual illusions

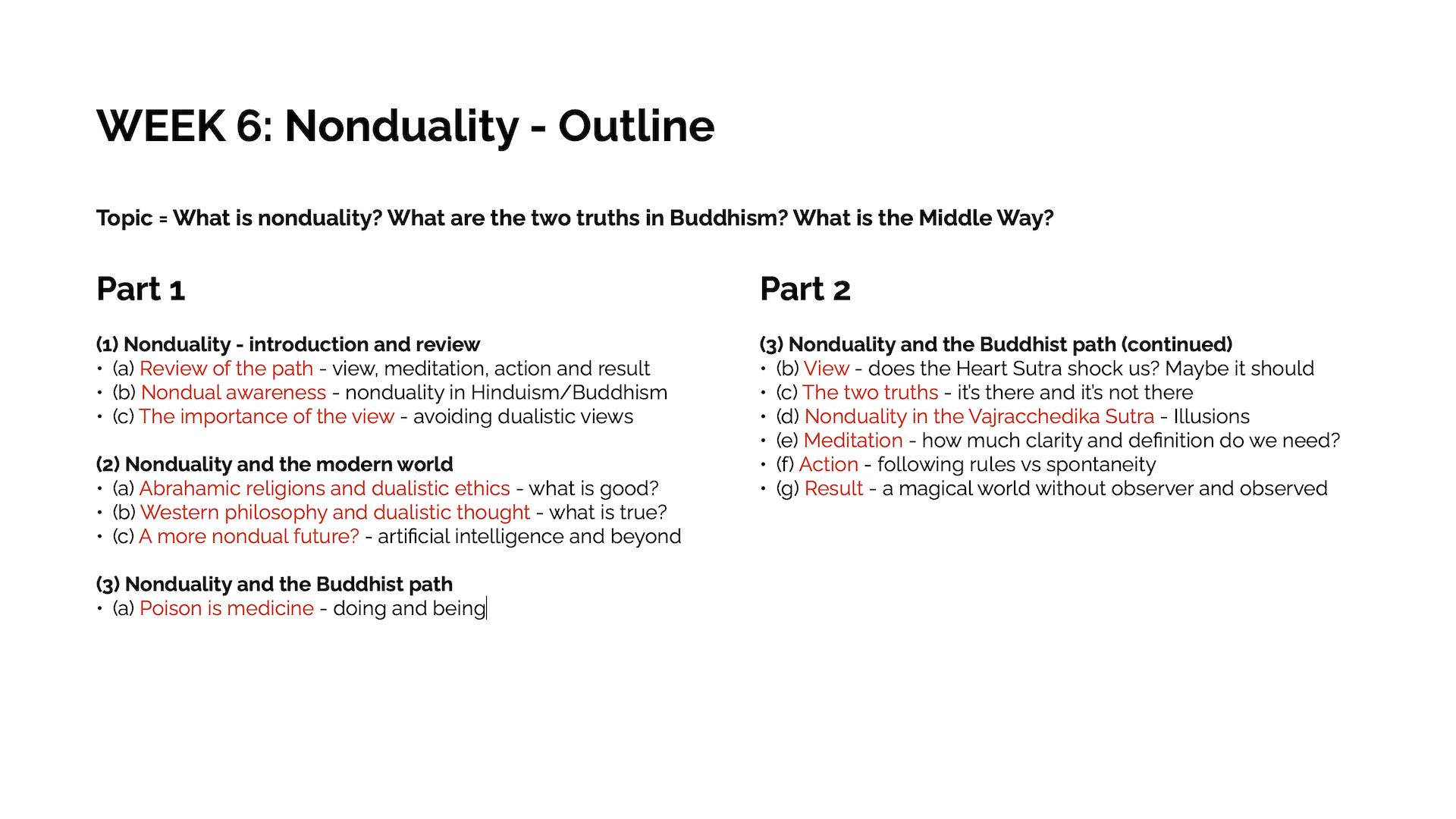

I’d like to show some examples of classic illusions to help make this point. You may be familiar with some of these, but I think they’re quite fun.

On the left is a famous illusion called the Kanizsa Triangle. If you look, you can see very clearly that there’s a [bright white upside-down] triangle in the middle of the image. Even though there’s nothing there, our brain interprets it as being there. Likewise, the image on the right is just a set of straight lines. And yet, our brain sees a bright [white] disc at the centre of the circle.

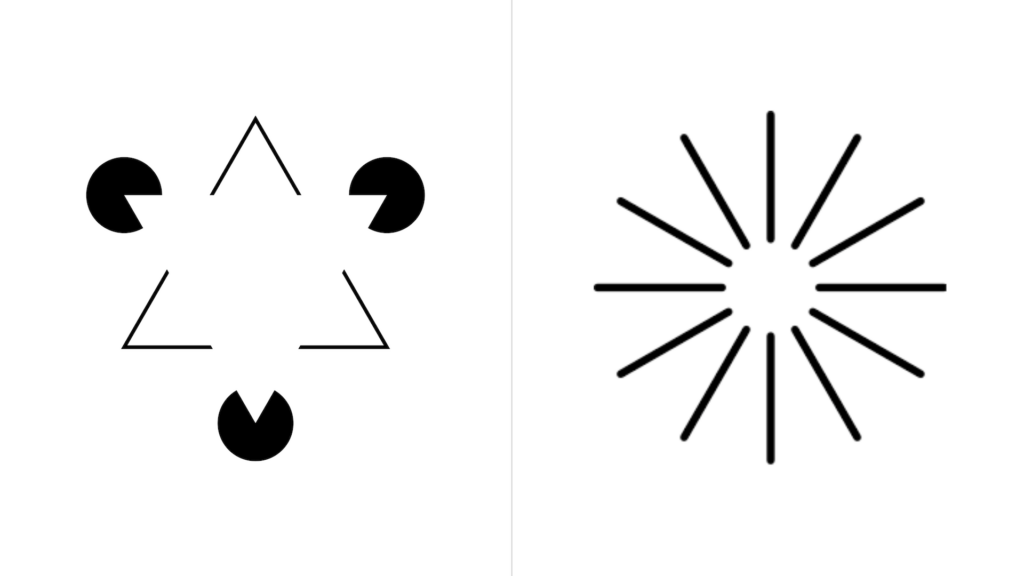

On the left, it looks like there is a sphere with spines. Your brain creates the illusion [of a sphere, even though there is no sphere in reality]. On the right, it’s exactly the same forms, just arranged differently on the page, and it looks like nothing in particular. The sphere has disappeared. This is a very Buddhist idea. We put a bunch of parts together arranged in a certain way, and it creates the illusion of something whole.

We have all these different parts of the self, [the five skandhas of form, feeling, perception, mental formations and consciousness]. It creates the illusion that there is actually a “self” that is made up of all of these parts. Just like the sphere on the left, it’s a very persistent illusion. We can’t shake it. Even if we know intellectually that there’s no sphere there. There it is.

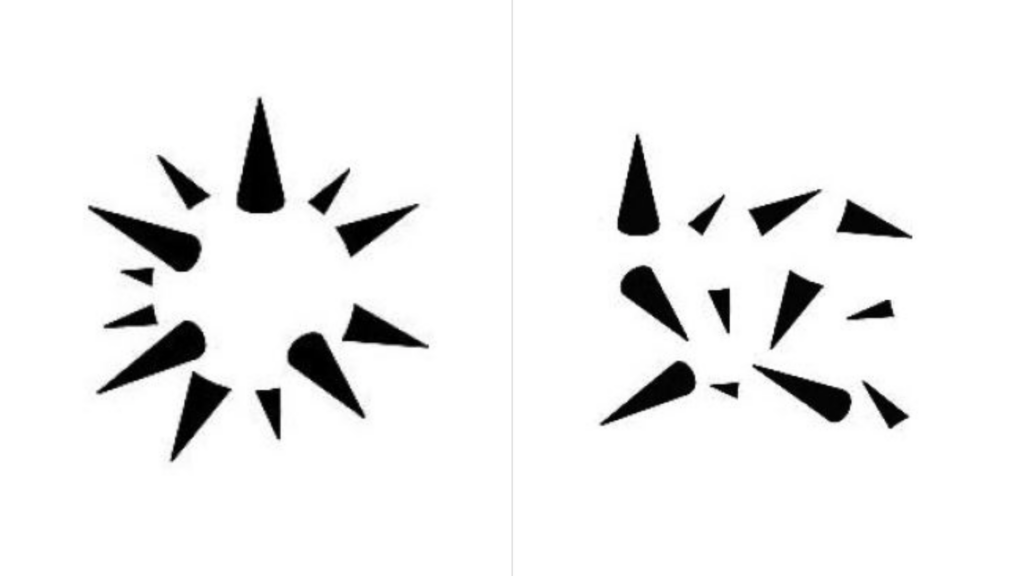

I like these two as well. The one on the left is called the café wall illusion. If you look at the image, you’ll be convinced the horizontal dividing lines are sloping. But if you get out your ruler and actually measure the lines, you’ll find they’re all perfectly parallel. But because of the way the black and white squares are aligned, our brain can’t help but see sloping lines.

The one on the right is also fascinating. If you look, you’ll see black dots. There are actually 12 of them, three rows with four dots in each row. And when you look directly at a dot you can see it, but as you turn your eye away it disappears. They’re only there when you look at them directly.

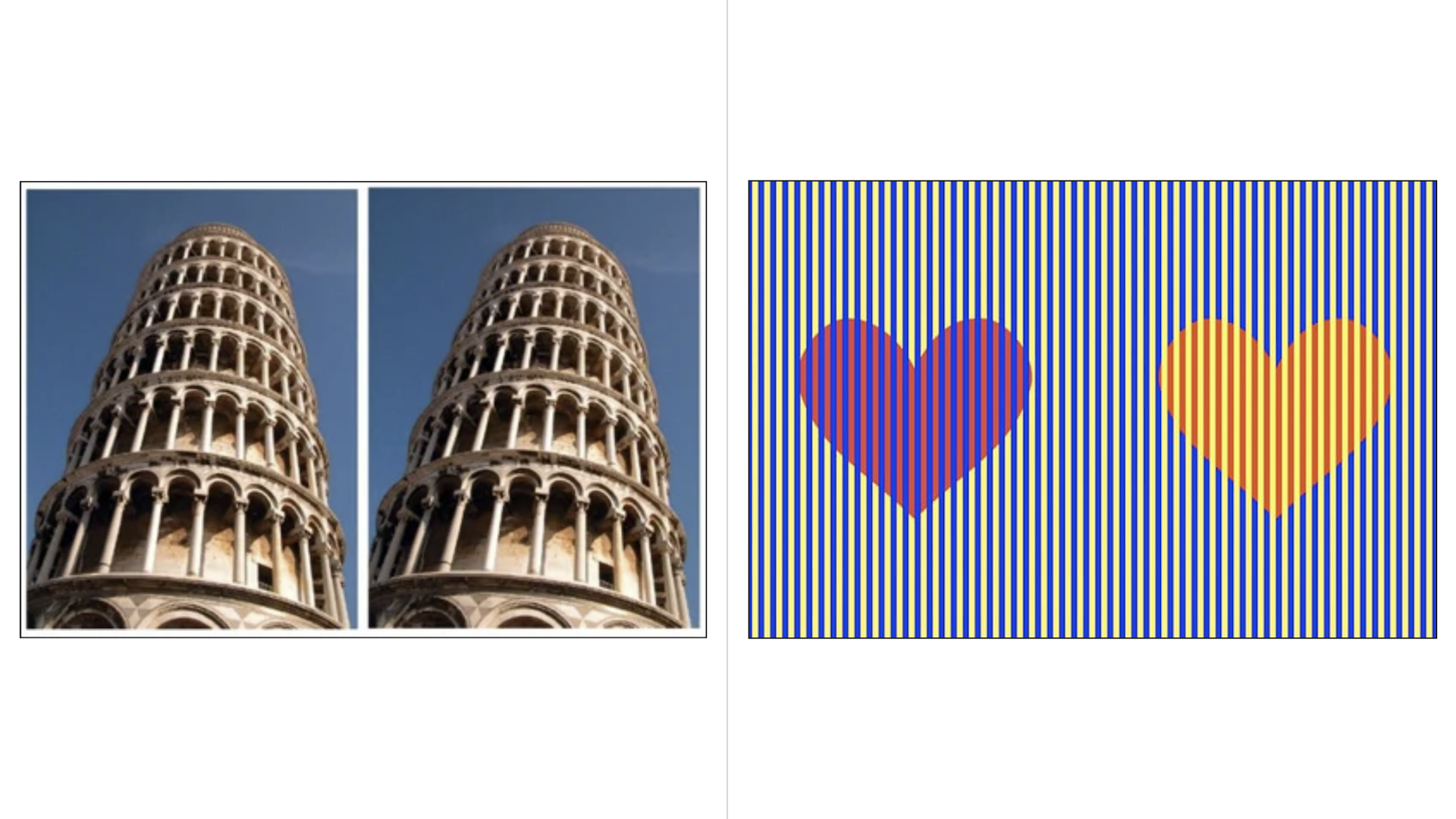

The one on the left won the Best Visual Illusion of the Year Contest in 2007. There are two identical photos of the Leaning Tower of Pisa. But the image on the right looks like it’s leaning more than the one on the left. They are identical.

The one on the right has two hearts. The heart on the left appears to be a dark pinkish colour, the heart on the right appears to be bright red. Actually, if you look closely, both are an identical colour of red. But because of what’s in front of the heart, whether it’s a blue line or a yellow line, we interpret what’s behind completely differently.

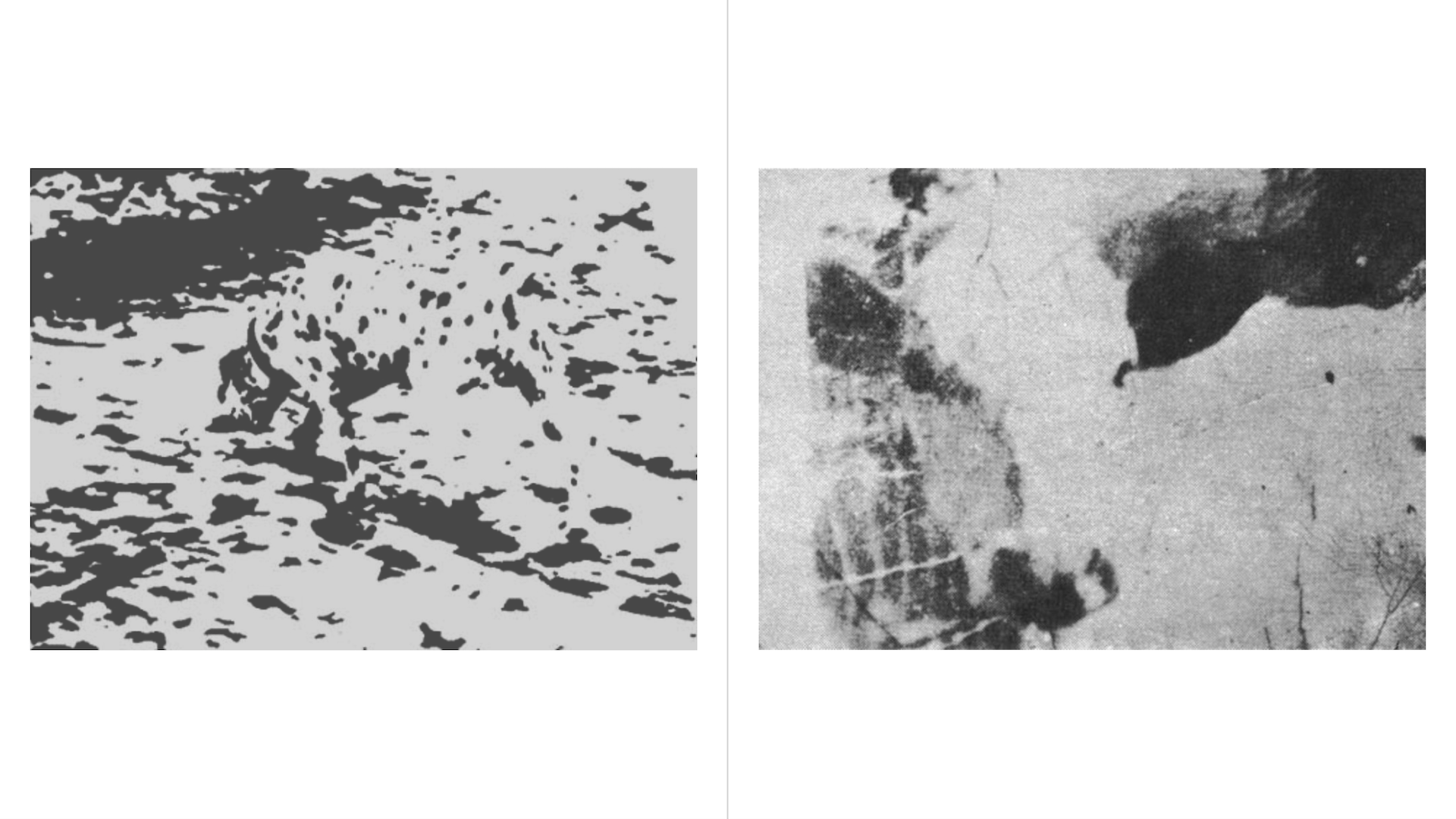

Two more. I’m not going to tell you what these are. If you haven’t seen these before, they’re both quite wonderful. When you first look at them, you may have no idea [what they are]. Each appears to be just a jumble of light and dark patches. But when you see each image, you’ll never forget it. And that image will then always be present for you if I show you this same jumble of light and dark patches in the future. [Once it arises, the illusion is persistent, again just like the illusion of the self].

This is very much how the path works, how the view works, and what it means to realize the truth. And how if we can understand non duality, it will completely transform our current experience.

An interlude: some more Zen stories

As a brief interlude, I’d like to give you some more Zen stories in the spirit of nonduality. The first story is about wisdom, once again from “The Gateless Gate”:

#43: Shuzan’s Short Staff

Shuzan held out his short staff and said: “If you call this a short staff, you oppose its reality. If you do not call it a short staff, you ignore the fact. Now what do you wish to call this?

The next story is called “Muddy Road”. This one is about the nondual way of thinking [or not-thinking] about doing the right thing. [It’s about spontaneous action], unencumbered by rules. It’s from the collection of “101 Zen Stories”:

#14: Muddy Road

Tanzan and Ekido were once traveling together down a muddy road. A heavy rain was still falling.

Coming around a bend, they met a lovely girl in a silk kimono and sash, unable to cross the intersection.

‘Come on, girl,’ said Tanzan at once. Lifting her in his arms, he carried her over the mud.

Ekido did not speak again until that night when they reached a lodging temple. Then he no longer could restrain himself.

‘We monks don’t go near females.’ He told Tanzan, especially not young and lovely ones. It is dangerous. Why did you do that?’

‘I left the girl there,’ said Tanzan. ‘Are you still carrying her?’

Next, another lovely story on living without all the usual ordinary worldly need to look good, to be seen as doing the right thing, to be concerned about reputation and so forth. It’s called “Is that so?”, from the collection of “101 Zen Stories”:

#3: Is That So?

The Zen master Hakuin was praised by his neighbors as one living a pure life.

A beautiful Japanese girl whose parents owned a food store lived near him. Suddenly, without any warning her parents discovered she was with child.

This made her parents angry. She would not confess who the man was, but after much harassment at last named Hakuin.

In great anger the parents went to the master. ‘Is that so?’ was all he would say.

After the child was born it was brought to Hakuin. By this time he had lost his reputation, which did not trouble him, but he took very good care of the child. He obtained milk from his neighbors and everything else the little one needed.

A year later the girl-mother could stand it no longer. She told her parents the truth — that the real “father of the child was a young man who worked in the fish market.

The mother and father of the girl at once went to Hakuin to ask his forgiveness, to apologize at length, and to get the child back again.

Hakuin was willing. In yielding the child, all he said was, ‘Is that so?”

All these stories have a bit of the flavour of nonduality, and I’d like to have a little of that spirit maybe seeping in for us.

(e) Meditation

Familiarizing ourselves with our espoused theory so that it becomes our theory-in-use

So let’s talk a little bit about meditation. We’ve said already that the aim of [Buddhist meditation or] practice is to realize the truth. But in some cases, the path is more direct than others. The signposts are more clearly laid out, the directions are clearer, and there’s much more contrast. Remember, meditation means “bhavana”, it means familiarization. It doesn’t necessarily mean sitting. It means becoming more familiar with the truth, so that it is available to us when we need it.

So for example, we might know intellectually that smoking is bad, but we might still smoke. We might know intellectually that too much time on social media is not good, but we still do it. We might know intellectually that we need to exercise more, but we don’t do it right. So just knowing something is not the same as having it available to us in a way that guides our action.

In the western psychology and leadership tradition [this idea of familiarization is explored in] the work of Chris Argyris and Donald Schön. Chris Argyris was a professor at Harvard Business School, and Donald Schön was a professor at MIT. They came up with the lovely idea of an “espoused theory” as opposed to a “theory-in-use”. We all have views or mental models, and our espoused theory is the one that we like to think is guiding our action. Indeed, maybe we have accepted it intellectually. Maybe we believe it is the right way to live.

But when it comes to our action, what’s actually behind it is our theory-in-use. For example, we think and we say that exercise is important, but we don’t exercise. So what is the actual theory-in-use that is guiding our behaviour? What explains why we don’t exercise? If we were to unpack it, we would find the reasons.

And, of course, our effectiveness is the extent to which our theory-in-use matches what we say we believe, our espoused theory. And the point of practice, then, is to align our espoused theory and our theory-in-use. In fact, you could also say this is a way of talking about authenticity. And that’s the whole point of bhavana, of familiarization. And, of course, it’s especially necessary when we’re under pressure, under stress, under duress. Let’s go back to that Bruce Lee quote again, “Under duress, we do not rise to our expectations, we fall to the level of our training”.

The journey from wrong view to right view to no view

And so the degree to which we need our path to be clear, obviously depends on our level of practice. How familiar are we with the distinctions of the path already? But it also depends on the nature of the environment. If our environment is very complicated, very noisy, we might need a much more high-contrast teaching to grab and hold our attention.