Alex Li Trisoglio

Public teaching given online in Madeira Park BC Canada

August 8, 2021

Part 1: 49 minutes, Part 2: 51 minutes, Part 3 (Q & A): 59 minutes.

Outline / Transcript / Video

Note: Transcription in progress (63% complete – Parts 1 & 2 complete)

Outline

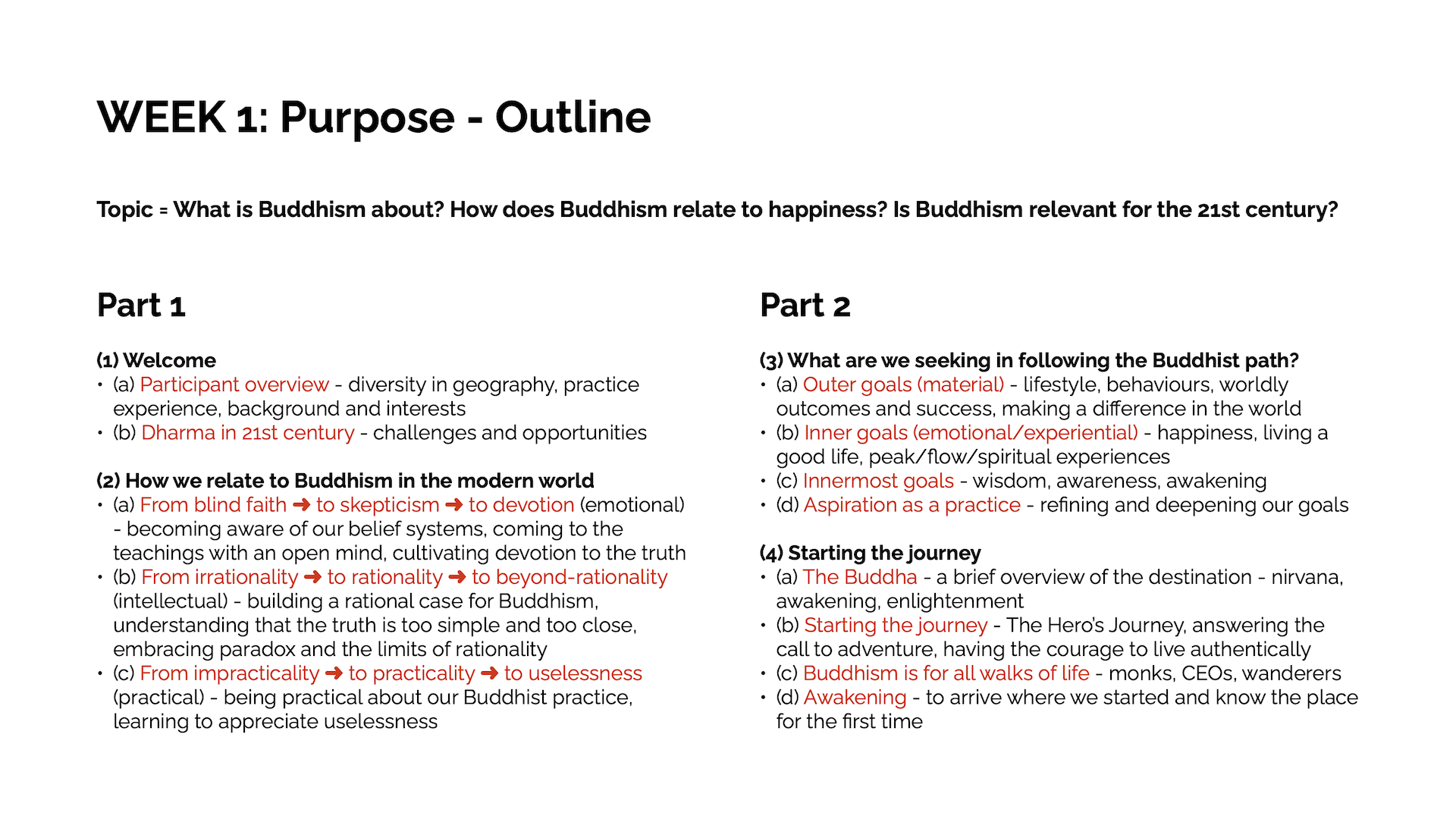

Part 1

(1) Welcome

(a) Participant Overview

This is an opportunity to reflect on our lives

Welcome. Good morning, good evening, everyone. Welcome to the first week of “Introduction to Buddhism”.

It’s a little bit of a sad time, in the sense that we’re losing our summer to COVID. For many of us, COVID has been quite a shock. It has revealed the fault lines in our lives, the unresolved issues. And for some of us, it’s been around our work. Do we actually want to be in an office? Do we want to commute? Are we going to be trapped at home in our tiny apartments with our families unable to actually be together?

For some people, it was their relationships with their partners. There has been a real spike in divorces because of COVID. And for many of us, it’s been [about] our relationship with ourselves. There’s been a big increase in loneliness, depression, and other kinds of mental health challenges. So for many of us, now’s really the time to ask, what does this mean for my life? Is there anything that I can take out of all of this, to make [my life] better?

A diverse global group of participants

And at the same time, many of us have been spending much of the last year in virtual gatherings like this one. And for me, it’s actually quite a wonderful thing, because something like this is normal today, but would barely have been possible 10 years ago. And it’s reflected in the diversity of the participants that we have. It’s not just geography — people have signed up from 54 countries — but also experience [with Buddhism], type of practice, and lineage.

We have all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism, indeed we’ve got representatives from pretty much all schools of Buddhism. We have a lot of people who are coming from a secular tradition, or a mindfulness tradition. We have a lot of people who are brand new and have no experience whatsoever. We’ve also got a lot of people who are culturally Buddhist, but have never really had much exposure to Buddhist teachings. And I would especially like to welcome all our friends from Bhutan who are joining.

And I’m particularly pleased that we also have a lot of Christians, Hindus, Muslims, people who are not Buddhist at all, but fascinated about meditation, what the Buddhist path has to say, and the nondual view.

We also have a real diversity in terms of people’s background. We have CEOs, we have university professors, and we’ve got just ordinary people. It’s really a snapshot of our world. And unlike many other communities, I’ve always loved that the Dharma community really brings people together across boundaries of class, wealth, or education.

Meeting the needs of both beginners and Vajrayana practitioners

Now in terms of this program, we do have a lot of complete beginners, and I really want to make sure we meet their needs. One of them said, and I quote, “I want the absolute essentials, in a simple way that relates to everyday life, the basics that anyone could get away with”. And I really hope we’ll be in a position to offer that.

There are also a lot of Tibetan Buddhist practitioners here, Vajrayana practitioners. And many of you have sent specific Vajrayana practice questions. I’m not going to address Vajrayana questions in a public setting. For those of you who haven’t seen Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s recent teaching on “Poison is Medicine”, he makes quite a [strong] point in that teaching about how there are reasons that the Vajrayana should be kept as more of a secret practice. And we can talk about that.

But for those of you who are Vajrayana practitioners, if there are enough of you that have interest and have questions, I would be happy to host separate sessions to talk about that. On the topic of questions, there is a link, I put it in the in the Forum, to a form where you can ask your questions. That link is active now, and it will be active throughout these teachings, and also the Q&A period. After this teaching, we will have Q & A starting at 12:00pm Pacific time. And I’m going to go through whatever questions are there. Now, unfortunately, because this is on YouTube, rather than Zoom, it’s not as interactive. But the chat is open, and if you do have questions, please submit them to that link in the forum.

I also want to say this is a teaching rather than a practice retreat. Now, many of you actually are interested in meditation as a practice. And we will certainly talk a lot about practice, and we will have an opportunity to do some practice together. But if you really would like more of an opportunity to do practice or retreat together online, please let me know. I’d be more than happy to arrange that over the coming weeks.

(b) Dharma in the 21st century

How Dharma is coming to the modern world – opportunities and challenges

As I say, we have a really amazing virtual global community here. There’s so much to share, and so much to learn from each other. I think it also represents something very interesting about the way the Dharma is coming to the modern world, which is something that Rinpoche has talked a lot about during his teachings over the past couple of years. And this is really something unprecedented. Because in Buddhist history until now, you’ve always had one particular lineage going from one country to one other country, a sort of linear kind of process.

But now, really for the first time, we have all of the Dharma available all at once, to all countries. It’s really unprecedented in Buddhist history. So it’s an incredible opportunity, and something quite wonderful. But it also comes with a number of challenges. And a big part of what we are going to talk about in these eight weeks is some of the ways that we can misunderstand Buddhism. There are many other introductions [to Buddhism] out there, and I encourage you to read them. Some of you asked for book references, I shall certainly provide those.

Identifying what is at the heart of Buddhism

But most of those don’t actually talk about where people can misunderstand the teachings. And it’s very easy for this to happen because of different language, different culture, different symbolism. From the outside it looks unfamiliar to many of us. And even within Buddhism, there’s so much difference. The stark simplicity of a Zen temple compared to the abundant richness of a Tibetan temple. You would be forgiven for thinking they’re completely different. But actually, the underlying wisdom, the underlying truth is the same.

So part of what we’re going to focus on is trying to separate out what is the actual core of Buddhism. What is the truth that all the traditions share? And what is something that’s more superficial? And I think that’s going to be important for us as we think about how, out of all of the different Buddhist resources that are available to us, how can we make sense of them? How can we determine which parts we actually need and want because they’re true, and which parts are just cultural adaptations?

(2) How we relate to Buddhism in the modern world

What is Buddhism? A very short summary

So, as a very brief summary, what would I say? What is Buddhism?

- [View] I would say that in its view, it’s a 2500 year old set of teachings and practices to see the truth — the truth about reality, about the world, about other people, and about ourselves. And of course about our minds.

- [Meditation] In its meditation, it has a complete path for training in wisdom, in compassion and kindness, and also in meditation and mindfulness.

- [Action] In action, it has a way of living in the world — at work and in relationships — but without getting lost, without getting caught up in the world.

- [Result] And as a result, it really is a way to find greater happiness, and freedom, awakening, enlightenment. Not just for ourselves, but for others.

So that’s the context. And that remains true. But I want to talk a little bit about some of the challenges of modernity. Three, in particular. This will give us an opportunity to start to talk a little bit about what do we mean [when we talk] about the Buddhist “Middle Way”. And it’ll also serve as an opportunity for me to give you a little background about myself, because some of you did ask about that.

(a) From Blind Faith to Skepticism to Devotion

The modern world prefers skepticism over blind faith

The first of these is skepticism and devotion. Now, one of the things we’re quite proud of in our Western intellectual history is that we’ve gone from the Middle Ages, the Dark Ages, a time of blind faith, to the Enlightenment, which has been very much a time of skepticism and questioning. Not just relying on tradition, or blind faith.

Many would say that we haven’t really quite gone far enough. And I think, if you look at politics. If you look at social media. If you look at advertising, if you look at fake news. If you look at the 2016 US election, if you look at Brexit, even the current wars around masks and vaccination, I think we can safely say, there isn’t perhaps enough skepticism [about the information that we are being given by political leaders, partisan news channels, and social media], or perhaps the wrong kind of skepticism out there.

So, we don’t want to go back to this blind faith and just believing things. But it’s a paradox. Because we say we need skepticism, but we also need devotion. So how can we do both? Well, let me step back a little first. If you find yourself still at [the stage of] blind faith, at least when it comes to your Buddhist path, I think we would say it’s perhaps a good thing because at least it will keep you connected [to the path].

But the Buddhist path is not a path of blind faith, although it is a path of devotion. Because you will need to cultivate some skepticism. You will need to build your experience so that you have the confidence that as you proceed on the path, you’re following a truth that makes sense to you.

Buddhism also values skepticism over blind faith

One of the most famous stories from the sutras is when the Buddha visited a town called Kesaputta, where the inhabitants were called the Kalamas. And they’d been visited by many teachers over the years. And they said to the Buddha, “Hey, you know, we’ve had all these different teachers, and they all offer us some different teachings. And yet they all seem to fight with each other. They all disagree and criticize each other’s teachings. Who should we believe?”

I think it’s much like trying to find a book on spirituality or meditation on Amazon. There are so many out there. Which ones [should we read]? How do we know what to believe?

And the Buddha’s answer was quite interesting. He said:

Don’t go by reports, by legends, by traditions, by scripture, by logical conjecture, by inference, by analogies, by agreement through pondering views, by probability, or by the thought, ‘This contemplative is our teacher.’ When you know for yourselves that, ‘These qualities are unskillful; these qualities are blameworthy; these qualities are criticized by the wise; these qualities, when adopted & carried out, lead to harm & to suffering’ — then you should abandon them.1From Kalama Sutta, AN 3.65, translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Available at Access to Insight.

So this idea is actually very contemporary. This idea that we really are responsible for coming up with our own point of view on how we should act in the world, what path we should follow.

We need to become our own coaches on the spiritual path

But it does put an enormous burden on the practitioner. And this has only grown more complex, as there are [now] so many sources of information about Buddhism out there.

And not just Buddhism, but the spiritual path, secular paths, self help, psychology. And of course, Buddhism and now mindfulness have become more popular, and lots of people are borrowing ideas [from Buddhism] and integrating them into their own teachings. And so it’s increasingly difficult to know what really is Buddhism, and what is Buddhism mixed with something else.

And then, of course, as has always been the case, we have charlatans, we have people out there trying to make money, who are offering populism rather than truth. There is fake news in Buddhism as well. There always has been. So we can be forgiven for feeling that we might be in over our heads.2See Kegan, Robert (1994) In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life.

We need a map, we need a guidebook. It’s like visiting a foreign country for the first time. And eventually, we’ll build one for ourselves. But that does take time. So one thing that I really want to try and help [you with] on this program is to give you some skills to do self-coaching on the path, because even if you have a teacher, you won’t be around your teacher all the time. And when it comes to the stresses of a moment where you have to make a decision, maybe a difficulty at work or an argument with your partner, you need your teachings to be available to you there and then for them to be useful.

Buddhism also values devotion

So yes, I would really like to find a way to give you a chance to build your own map. Now, as I said, Buddhism has skepticism, it has this message the Buddha gave to the Kalamas. But it also has devotion. The Sanskrit word [for devotion] is bhakti3bhakti (Sanskrit: भक्ति) = devotion, fondness; trust, faith; homage, worship – see dépa., which has the meaning of devotion or fondness or trust or faith, even homage. Another [Sanskrit word for devotion] is shradda4shradda (Sanskrit: श्रद्ध, IAST: śraddha) = having faith, belief, trust, confidence – see dépa., which means faith or belief or trust.

Now, if you look up the English word “devotion” on Google, you’ll find the following definition:

love, loyalty, or enthusiasm for a person, activity, or cause.

“his courage and devotion to duty never wavered”

religious worship or observance.

“the order’s aim was to live a life of devotion”

So yes, devotion has those connotations of love and loyalty and enthusiasm. But it also has a second meaning in English of religious worship. And I think a lot of people have the sense when they hear the word “devotion” applied to Buddhism, they think, “Oh, this sounds an awful lot like a religion” and they start getting suspicious.

Devotion has many meanings

We’re going to find through these eight weeks that there are a lot of challenges with language, with the translation of terms. And the connotations that we apply [to words]. Rinpoche talks a lot about the difficulties of growing up in a world where we’ve had 2000 years of a Judaeo-Christian or Abrahamic tradition. Where even words like “good” have a very particular connotation for us, even if we’re very secular. Just by speaking English, we can’t really avoid the way that a word comes loaded with all kinds of meanings, which we may not even be aware of.

But I will say of course, there is a bad version of devotion. [Devotion in Buddhism] doesn’t mean, of course, an unquestioned loyalty to a cult leader. For those who haven’t seen “Wild, Wild Country”, the documentary series about Bhagavan Shree Rajneesh, it’s quite wonderful5Rajneesh, also known as Osho, was famous for owning 93 Rolls Royces. He saw no contradiction between owning all these Rolls-Royces and the spiritual path. He said:

“People are sad, jealous, and thinking that Rolls Royces don’t fit with spirituality. I don’t see that there is any contradiction… In fact, sitting in a bullock cart it is very difficult to be meditative; a Rolls Royce is the best for spiritual growth.”

See wikipedia.. Recently, we’ve had the NXIVM cult6NXIVM was an American cult that offered spiritual and professional development programs while also engaging in sex trafficking, forced labor and racketeering. Its founder Keith Raniere was convicted in federal court of sex trafficking and racketeering in June 2019 and sentenced to 120 years in prison. Even after his conviction, he has continued to direct loyalists from behind bars, encouraging continued recruitment. Members of NXIVM have regularly danced outside Raniere’s jail and staged coordinated protests, and it is estimated that about 50 to 60 people remain loyal to Raniere – see wikipedia.. And of course, there have been lots of challenges and even abuse within Buddhism itself7For example, the blog “Buddhism Controversy” writes about scandals and abuse within several different schools of Buddhism – see Buddhism Controversy.. So we’re far from free from that ourselves.

We all believe in something, even the most skeptical among us

But the opposite extreme isn’t the answer either, is it? I think a lot of modern people would say, “Oh, I don’t have any beliefs. I don’t follow any kind of fixed things like that”. But I don’t think that’s true. I think we all believe in something.

I was reminded of Le Chiffre, the nihilist antihero in the James Bond movie “Casino Royale”. At the beginning [of the movie] a warlord who was looking for some unofficial financing goes to Le Chiffre and says to him, “Do you believe in God, Monsieur Le Chiffre?” And Le Chiffre says, “No, I believe in a reasonable rate of return”.

I think that’s a message for all of us. Yes, maybe we don’t think we have a religious belief. But our life necessarily has something that’s driving us. We do believe in certain things. I’ve always liked the quote from the Nobel economist, John Maynard Keynes, when he said8In “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money” (1936) – see wikiquote.:

“The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else.”

And this is the part I really like:

“Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist […] it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil”

We will [be coming back to this] a lot during these eight weeks. We will talk about our underlying views, our underlying belief systems. What is it, even if we don’t necessarily articulate it every day, that is really driving the choices in our lives?

Where are we devoting our time and energy?

So in Buddhism, yes, devotion is there, but it’s devotion to the Three Jewels — the Buddha, the Dharma, which is the teachings, and the Sangha, which is the community of practitioners. We’ll talk about this more in future weeks. But if you were to boil it down to just one idea, [the Buddhist path] is really about devotion to the truth.

So I invite you, maybe not right now, but perhaps after this course, to think about this for yourself:

REFLECTION:

What is your North Star? What do you devote your time, energy, attention and resources towards? You can start by writing down what you think your purpose is, and then compare how you actually spend your days [to what you say is important to you].9This is a simplified version of the “Taking Stock” exercise from “Do Your Commitments Match Your Convictions?” by Donald Sull and Dominic Houlder in the January 2005 issue of Harvard Business Review.

The topic of purpose is very significant within the leadership literature, and another frequently cited article that may serve as a helpful introduction is “Discovering Your Authentic Leadership” by Bill George et al. in the February 2007 issue of Harvard Business Review.

Because it turns out, very few of us are even aligned with our stated purpose [as we think of it today], let alone what we think we would like [to have done with our lives by the time] we retire. Or if we were on our deathbed. As a thought experiment, people often ask “If you knew you’re going to die in six months, what would you do?” For most of us, it would be something different from the way we’re choosing to spend our days today.

And yet, one day leads to another. The days lead into to months which become years. And somehow we never seem to change our habits. The psychologist Dan Gilbert has this lovely idea that our current self is very bad at predicting what our future self wants10See Gilbert (2006) “Stumbling On Happiness”. In the Foreword, he writes:

“No one likes to be criticized, of course, but if the things we successfully strive for do not make our future selves happy, or if the things we unsuccessfully avoid do, then it seems reasonable (if somewhat ungracious) for them to cast a disparaging glance backward and wonder what the hell we were thinking. They may recognize our good intentions and begrudgingly acknowledge that we did the best we could, but they will inevitably whine to their therapists about how our best just wasn’t good enough for them.”. And I think that’s a real cause for much of the unhappiness that we end up finding for ourselves within our lives.

Devotion to our teachers

By the way, for those of you who are not familiar with the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, you will hear me use the word “Rinpoche”, and I just want to say what that is. It’s actually a word that literally means “precious one”11Rinpoche (Tibetan: རིན་པོ་ཆེ་) = “precious one”, honorific title for a teacher – see Rinpoche.. It’s an honorific. It’s the way we refer to our teachers. Within the Indian and the Tibetan traditions, I think the importance of lineage, the gratitude towards teachers is really held as important. Much as it was, I think, even in the ancient Greek tradition of philosophy.

Rinpoche loves to tell the following story about the great sitar player Ravi Shankar. Once when he was playing in London, his guru Allaudin Khan was in the audience. And I think Ravi Shankar did not know that [he was going to be there] before the performance. But he spotted him just before he started to play. And before he even started, he put down his sitar, and he walked off the stage and into the audience. And he prostrated three times to his teacher. And then he went back [onto the stage] and started his performance.

I’ve always loved that story, I think it says something quite important about being willing to have the humility to acknowledge [those] who have been our teachers. Basically, where have we found wisdom in our lives?

Our projections of our teacher

On the topic of teachers though, much though it is important to learn to cultivate devotion to the teacher and the teaching — especially if you’re following a Vajrayana path — it’s also important, as we said, not to fall into blind faith. And I think to become aware of how our relationship with our teacher is driven by our own projections. Any of you who’ve ever been in therapy will be familiar with the ideas of transference and countertransference, how we project our own hopes and fears, our own unresolved issues onto our therapist. And actually, it turns out, we all do something very similar with our teachers on the spiritual path.

REFLECTION

I invite you to approach your teacher with that kind of attitude of noticing — what are your hopes and fears and projections? And maybe think less about what [your view of your teacher] says about your teacher, and more about what does that say about you?

Ideally, your teacher really should be not just an embodiment of wisdom and a skilful coach, but a compassionate mirror, someone who can allow you to see yourself more clearly. Where you can really see your ego games being played out. A little like a therapist, but more so. Because it’s not just about your inner psychological world, but your innermost world of awareness and wisdom.

Just to say a little about me. I’ve been a student of Rinpoche for a long time. I’m very fortunate to have received many teachings from him in many places. From the high mountains in Bhutan, to beside the Ganges, even under the Bodhi Tree in Bodh Gaya. So it really means a lot to me to be able to share what I’ve learned with you.

Approaching Buddhism with an open mind

Although in my case, my first encounter with Vajrayana was quite negative, I had a very reactive attitude [upon] seeing the [Tibetan thangka] paintings of [what I interpreted as being] demons. Seeing the way that people seem to be so clingy and so subservient to their teachers. It didn’t sit well with me at all. So I can understand why people may see that whole scene and decide it’s not for them. I can also really understand why secular Buddhists find a lot to disagree with in Buddhism. But I really would like to invite you, especially if you’re one of those secular Buddhists yourself, to approach this with an open mind, if only for these eight weeks.

It’s very easy to judge things we don’t understand, to think, “Oh, it’s ancient, it’s outdated, it’s old, it’s unfamiliar.” Maybe we also try and force Buddhism into our own terms [and categories]. We think, “Well, is it a religion? Is it a philosophy? Is it a psychology, a mind training? A path of personal transformation?” Well, yes, it’s all of those things. And perhaps it’s none of those things.

One of my favourite Zen stories is called “A Cup of Tea”12“A Cup of Tea” is the first of “101 Zen Stories”, a compilation of koans by Nyogen Senzaki, a Rinzai Zen monk who was one of the 20th century’s leading proponents of Zen in the United States. These stories are published in “Zen Flesh, Zen Bones”, a 1957 book by Paul Reps which offers a collection of accessible primary Zen sources on emptiness and nonduality. The 101 Zen Stories are also available online at various sites, including AshidaKim.:

Nan-in13A Japanese Zen master during the Meiji era (1868-1912). received a university professor who came to inquire about Zen.

Nan-in served tea. He poured his visitor’s cup full, and then kept on pouring.

The professor watched the overflow until he no longer could restrain himself. “It is overfull. No more will go in!”

“Like this cup,” Nan-in said, “you are full of your own opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?”

This is the beginning, the first of [the collection of] 101 Zen stories. And I would really invite you to approach these teachings with openness. Try to bring a beginner’s mind and empty cup as best you can. I know that’s not always easy. And personally, I’m really grateful that we have Christians, Hindus, and Muslims here [attending these teachings]. I think it’s wonderful. It says a lot that they, that you, are open to questioning what you’ve learned, and to hearing things from different traditions.

I believe that Buddhism really offers something that goes beyond all countries, all nationalities, all human social systems and really taps into something much more fundamental about what it is to be human, and even what it is to be conscious. Rinpoche has talked quite a lot over the years, and more recently, about what will happen when AI, artificial intelligence, takes over. Of course, there will impacts for our jobs and livelihoods and our sense of purpose.

But I think raises a whole other interesting set of questions about what if these AIs themselves start approaching consciousness? How then will we relate to them? And it’s a not a joke. What if they suffer? [What if they start looking for a path to transform their suffering?] What if they want to study and practice Dharma? How will that go? So we can talk more about that also.

(b) From Irrationality to Rationality to Beyond-Rationality

The modern world prefers skepticism over blind faith

The second big theme is about rationality and going beyond rationality. The modern world has gone from irrational to rational, scientific, and evidence-based. But Buddhism asks us to go beyond the limits of rationality, to embrace a world of paradox. And as before [with the progression from blind faith to skepticism to devotion], this does not mean going backwards towards irrationality, but going forwards in such a way that we can include and hold both the rational and the beyond-rational.

Of course, we do still have to go beyond irrationality. So if you’re someone who hasn’t yet fully embraced rationality, perhaps this is an opportunity for you. One of the three poisons that is spoken about in the original Pali teachings is moha14moha (Pāli: मोह) = delusion, confusion, bewilderment; one of the 3 poisons outlined in the Theravada teachings – see moha., which is defined as ignorance — in particular the ignorance of cause and effect or the ignorance of reality. We could paraphrase and say that [this ignorance] is a form of irrationality.

Being less irrational about our lives

There are many teachings and practices to help us through that. But one in particular that I’d like to offer now is from the Vajrayana. It is part of the Ngöndro, which are the preliminary teachings and practices15Ngöndro (Tibetan: སྔོན་འགྲོ་) = preliminary practices – see Ngöndro. An extensive traditional Tibetan commentary on these four thoughts may be found in “The Words of My Perfect Teacher”, Patrul Rinpoche’s classic introduction to the Ngöndro. I recommend the translation by Padmakara Translation Group.

An English translation of the Four Thoughts from the Longchen Nyingtik Ngöndro appears in the section “The Four Thoughts that Turn the Mind from Saṃsāra”, part of “The Excellent Path to Omniscience: The Dzogchen Preliminary Practice of Longchen Nyingtik”, available free online at Lotsawa House. Translations are also available in French, German and Spanish.. These [preliminary teachings include] four thoughts [that you contemplate in order] to turn your mind away from samsara, and encourage you to practice the Dharma. [We can reflect on these four thoughts as a way to question how we ignore cause and effect when it comes to our own happiness and fulfillment, and how we ignore important parts of our own reality and the circumstances of our lives]. I’ll just paraphrase them here16Ed.: In the live teaching, I presented the third and fourth of these four thoughts in the opposite order. This has been corrected.:

- (1) Opportunity: The first (reflection) is to appreciate the opportunity that we have to hear these teachings, to have enough space in our lives to actually do something with them. To even have the interest that attracts us [to these teachings] in the first place. Now that we have found this, what on earth will we do? There’s a lovely poem called “The Summer Day” by Mary Oliver that’s often used in mindfulness programs, which end with the beautiful lines17Mary Oliver (1935-2019) was a Pulitzer Prize winning poet. Her poem “The Summer Day” is Poem 133 in the Library of Congress.:

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

This is the same idea. We have this freedom right now [to study and practice the Dharma]. We don’t know if we’re always going to have it. Are we really using it? Are we really thinking about [and acting upon] what is most purposeful to us?

- (2) Impermanence: Next is impermanence. We tend to not pay attention to how things pass, how opportunities go. We leave things unfinished. How many New Year’s resolutions do we not complete with the idea that we’ll get round to them one day? [Will our current interest in Buddhism suffer a similar fate?]

- (3) Action: Third is the idea of action or karma [or causality]. The idea that what we do really matters. Our current actions, our current thoughts [have consequences]. They really determine [our life] tomorrow and in the years ahead. [As we discussed earlier, the thoughts and actions of our current self will determine the happiness of our future self, even if we’re unwilling to admit it].

- (4) Samsara: The final thought is about the defects of samsara or worldly life. We keep trying to fix our outer life, but it never seems to work. I’m not saying we should be careless or lazy, or just give up. Far from it. But we could start to ask ourselves, is there perhaps more that we’re not paying attention to? [Is this really how we want to spend our days and years?]

So all of these are ways of saying that we can’t just be blasé, not really pay attention, not care. There are good reasons for paying attention to the way we relate, to how we think, how we approach our lives, how we approach Buddhism.

Contemplating a more rational life in western philosophy

This is not just found in Buddhism, by the way. There is also a rich tradition of similar contemplations in the western philosophical tradition. For example, Stoicism has this also. You can look at the great Stoics such as Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius. They had very similar ideas. I just looked at the writings of Marcus Aurelius, and I found four of his maxims that really match up with the four thoughts18Ed.: In the live teaching, as with the four thoughts, I presented the third and fourth of these quotes from Marcus Aurelius in the opposite order. This has been corrected.:

(Opportunity) “Think of the life you have lived until now as over and, as a dead man, see what’s left as a bonus”

(Impermanence) “You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.”

(Action) “Waste no more time arguing what a good man should be. Be One.”

(Samsara) “It’s time you realized that you have something in you more powerful and miraculous than the things that affect you and make you dance like a puppet.” We don’t just have to respond to social media and ads that we see on Facebook and Google. We don’t have to live our lives by these people who are manipulating and making us dance.

So yes, Buddhism cares a lot about rationality. [Cultivating a] correct understanding and relationship to reality. Seeing the truth. And this love of truth is very much shared with Western philosophy. But here, there’s even more. We’ll say, yes, there’s something else that maybe Western philosophy hasn’t necessarily seen.

The truth is too simple and too close

I do want to touch on something that one of you wrote. You quoted the American Buddhist teacher Elizabeth Mattis Namgyal who said, “If you cannot explain it to a six year old, you do not know it yourself”. And I really sympathize with that. But I’m not entirely sure we’re going to be able to manage to do that. Because although Buddhism is experientially very simple, it’s made complicated because of the confusion we bring to it.

There’s a lovely story by David Foster Wallace called “This is Water”19“This is Water” is David Foster Wallace‘s 2005 commencement speech to the graduating class at Kenyon College. An audio recording and transcript are available at the FS blog.. And he begins with a parable20In the live teaching this parable was paraphrased. The quote below is David Foster Wallace’s actual words.:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

I think that’s really starting to point us towards what is beyond our normal rationality. The teachings often say that our own awareness, the nature of our own mind, is too close [for us to be able to see it easily], like our own eyelashes. It’s too simple. It’s also a bit like saying that we can’t see the forest for the trees.

And sometimes cowherds can realize things that university professors might not. And vice versa. Sometimes university professors can see things a cowherd might not. But it’s really not about the contents of our thoughts and our mind, as much as [it is about] the relationship between our mind and our awareness, or the contents and the container. Or, we might say, the fish and the water.

Having a map, but not getting caught in the map

If we’re just focusing only on rationality (i.e. if we’re operating only at the contents level of language, logic, and reason)21The history of logical positivism and logical empiricism, which are both 20th century movements in western philosophy, is instructive in this regard – see wikipedia and Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy., we might never step back and see the broader container that is our awareness. It’s very hard for us to step back, to really have beginner’s mind. So the path is going to be an undoing. But it’s not about erasing the mind. It’s not like trying to clear a hard disk or something. It’s not trying to get back to a pure blank slate, not that we ever had one. That would be impossible.

It’s also useless. And you can see the effects (of what this might look like) with the unfortunate stories of people with traumatic brain damage. There’s a wonderful book by [neurologist] Oliver Sacks called “The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat”22“The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales” is a 1985 book by neurologist Oliver Sacks describing the case histories of some of his patients. Sacks chose the title of the book from the case study of one of his patients who had visual agnosia, a neurological condition that leaves him unable to recognize faces and objects – see wikipedia.. The case history that gives the book its title is a literal truth. It’s a true story. Now, could you say that this man has “unlearned” something? Well, yes, of course, but not in a way that’s helpful.

We still need our maps of the world, we still need a way to get through life. So the Buddhist path can’t only be about changing our thoughts, although we know we’ll need to change some of them as we proceed along the path. I think it’s more around how do we change our relationship to our thoughts? [Our relationship to] our emotions, our experiences, our mind? Indeed, [how do we] change our relationship to our ideas of self, others, world?

Is this difficult? Can you explain it to a six year old? I’m not sure. I don’t know23Ed.: And even if we can explain enough of the view to enable someone to follow the path, it doesn’t mean that we have really been able to explain foundational ideas like “mind”, “awareness” and “consciousness” – which ought to be at least somewhat concerning for a path that purports to offer a training of this not-fully-explained mind. For example, see some recent discussions of consciousness/AI in the blogs of Scott Alexander and – only for those who are mathematically inclined – Scott Aaronson.. Can you explain how to make a chocolate cupcake to a six year old? Maybe. Can you explain how to make a Viennese Sachertorte to a six year old? Maybe it’s a little harder. Now, does that mean we shouldn’t try to teach anyone how to make a Sachertorte? I don’t think we’re saying that either. By the way, in case none of you have experienced [a Sachertorte], it’s one of my favourite Viennese specialities24For the history of the Sachertorte, see wikipedia. If you would like further inspiration, there’s an inviting set of Sachertorte images at Getty Images.. It’s a dense chocolate cake, with a thin layer of apricot jam (in the middle), coated in dark chocolate icing on the top and on the sides. But it’s well known as being a very hard and complex cake to make25Vallery Lomas, the winner of Season 3 of ABC’s “The Great American Baking Show”, describes it as “The most complex, complicated thing I’ve ever made”.

The example of cupcake and Sachertorte has also been used to illustrate computational complexity theory. We can say that a Sachertorte is more complex than a chocolate cupcake, because the shortest possible recipe (i.e. algorithm) for a cupcake is far shorter than the shortest possible recipe for a Sachertorte – see wikipedia. See also John Shore (1985) “The Sachertorte Algorithm” and John Holland (1995) “Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity”.

For additional discussion about types of problem that could never be solved in practice, see the discussion of P, NP, and NP-Hard problems in wikipedia..

Nonduality, paradox, and going beyond rationality

So that’s [a little bit about irrationality and] rationality. As for going beyond rationality, we’re going to spend a lot of our time during the eight weeks on that. So I won’t say too much right now, just to say it will be a big theme26For philosophically inclined readers, a taste of “beyond rationality” can be found by dipping into Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika, “Root Verses on the Middle Way”. For example:

XXII:11

We do not assert “Empty.”

We do not assert “Nonempty.”

We assert neither both nor neither.

They are asserted only for the purpose of designation.

– translation: Jay Garfield

Garfield explores this verse in Chapter 3 of his book “Engaging Buddhism”, where he writes:

Nāgārjuna makes it plain that even the statement that phenomena are empty of intrinsic nature is itself a merely conventional truth, which, in virtue of the necessary involvement of language with conceptualization, cannot capture the nonconceptualizable nature of reality. Nothing can be literally true, including this statement. Nonetheless, language—designation—is indispensible for expressing that inexpressible truth. This is not an irrational mysticism, but rather a rational, analytically grounded embrace of inconsistency. The drive for consistency that many philosophers take as mandatory, the Mādhyamika argues, is simply one more aspect of primal confusion, a superimposition of a property on reality that it in fact lacks. An important implication of Madhyamaka metaphysics is hence that paraconsistent logics may be the only logics adequate to reality. This, too, would be a valuable insight to take on board.

For additional notes on paraconsistency and dialetheism, see Graham Priest on “Paraconsistent Logic” in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.. And for those of you who come especially from a Zen tradition, you’ll be familiar with this, because paradox and going beyond rationality are very much themes in the Zen teachings and practices.

Many of you may have heard the famous koan about “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” On its surface, it literally makes no sense. It’s an irrational statement or question. And yet, it’s key to the practice [of nonduality]27Ed.: This koan is #21 in the collection of 101 Zen Stories. The full text of the koan was not part of the live teaching, but is included below. It may also be accessed at AshidaKim.:

The master of Kennin temple was Mokurai, Silent Thunder. He had a little protégé named Toyo who was only twelve years old. Toyo saw the older disciples visit the master’s room each morning and evening to receive instruction in sanzen or personal guidance in which they were given koans to stop mind-wandering.

Toyo wished to do sanzen also.

“Wait a while,” said Mokurai. “You are too young.”

But the child insisted, so the teacher finally consented.

In the evening little Toyo went at the proper time to the threshold of Mokurai’s sanzen room. He struck the gong to announce his presence, bowed respectfully three times outside the door, and went to sit before the master in respectful silence.

“You can hear the sound of two hands when they clap together,” said Mokurai. “Now show me the sound of one hand.”

Toyo bowed and went to his room to consider this problem. From his window he could hear the music of the geishas. “Ah, I have it!” he proclaimed.

The next evening, when his teacher asked him to illustrate the sound of one hand, Toyo began to play the music of the geishas.

“No, no,” said Mokurai. “That will never do. That is not the sound of one hand. You’ve not got it at all.”

Thinking that such music might interrupt, Toyo moved his abode to a quiet place. He meditated again. “What can the sound of one hand be?” He happened to hear some water dripping. “I have it,” imagined Toyo.

When he next appeared before his teacher, Toyo imitated dripping water.

“What is that?” asked Mokurai. “That is the sound of dripping water, but not the sound of one hand. Try again.”

In vain Toyo meditated to hear the sound of one hand. He heard the sighing of the wind. But the sound was rejected.

He heard the cry of an owl. This also was refused.

The sound of one hand was not the locusts.

For more than ten times Toyo visited Mokurai with different sounds. All were wrong. For almost a year he pondered what the sound of one hand might be.

At last little Toyo entered true meditation and transcended all sounds. “I could collect no more,” he explained later, “so I reached the soundless sound.”

Toyo had realized the sound of one hand.

So for those of us who are stuck in our rationality, maybe there’s something that we’re missing, maybe there’s something we haven’t fully understood yet.

The simplicity on the far side of complexity

I’m trained as a scientist, as a theoretical physicist. I attended lectures by Stephen Hawking when he was still able to use his hand to operate his speech synthesizer28Stephen Hawking (1942 – 2018) was an English theoretical physicist and cosmologist. He was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge between 1979 and 2009. He is well known for his contributions to general relativity and cosmology, including the theoretical prediction that black holes emit radiation, often called Hawking radiation. In 1963, Hawking was diagnosed with an early-onset slow-progressing form of motor neurone disease that gradually paralysed him over the decades. After the loss of his speech, he communicated through a speech synthesizer initially through the use of a handheld switch, and eventually by using a single cheek muscle – see wikipedia.. So yes, I appreciate rationality. But there’s so much that rationality doesn’t cover even in the world of physics. I won’t go into that [now], but there’s a lot there.

And in our modern world, as we discussed earlier, there’s so much in politics and advertising and so forth where we are not rational. But I do want to say to all the secular Buddhists and the skeptics and the rationalists out there, please bear with it, even if initially, you might think this idea of going beyond rationality makes no sense.

And also, for those of you who really want things to be simple, please don’t give up if the path at times may seem difficult. As Oliver Wendell Holmes is supposed to have said29Ed.: although this quote is quite well-known and oft-cited, its origins are obscure and contested. It’s not even clear whether the quote should be attributed to Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the famous US jurist, or his father Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. For discussion see wikiquote and the wikiquote talk page.:

“I wouldn’t give a fig for the simplicity on this side of complexity;

I would give my right arm for the simplicity on the far side of complexity”

Any of you who’ve tried to master anything in life, you know that you can’t get to the wisdom of simplicity by ignoring the complexity. It’s the same with difficult decisions in life. To pretend they’re simple and try to solve them by flipping a coin doesn’t actually mean you’ve made a wise choice. Some of us are busy right now watching the Olympics. The simplicity — or seeming simplicity and effortlessness — of a perfectly executed gymnastic routine, or a beautifully played piano sonata, only comes after a lot of practice and hard work.

Why should we expect Buddhism to be different? As Einstein is supposed to have said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler”30This quote is also contested. It’s not clear that Einstein ever used these words, although he did say something similar (albeit less simple!):

“It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience”.

See QuoteInvestigator.. And it’s very similar and very true also in Buddhism, and Rinpoche has often expressed his concern that many contemporary explanations of Buddhism are going a little too far perhaps towards populism and simplicity.

And if you do that, then all you’re going to do is relate the teachings back to what you knew before you started. It reminds me, coming from England myself, how if you go to the Costa del Sol in Spain, you will find many beautifully arrayed English fish and chip shops31A search made in August 2021 for “Costa del Sol Fish & Chips” on TripAdvisor yielded 67 results – see TripAdvisor. In her 2000 book “The British on the Costa del Sol”, Karen O’Reilly cites Ian McKinnon writing in 1993 in the Independent on Sunday. He describes Britons living in the Costa del Sol as:

“. . .living in ghettos, speaking no Spanish, buying fish and chips and British beer, and having little to do with the Spanish”.. So yes, it’s very familiar. It’s very simple. It’s easy to get fish and chips on the Costa del Sol. But are you really experiencing anything to do with Spain? [Likewise, it’s quite possible to make Buddhism into something that sounds familiar and comfortable to our modern rational ears. But does that have anything to do with the actual teachings of Buddhism?]

(c) From Impracticality to Practicality to Uselessness

The modern world prefers practicality and efficiency over impracticality and laziness

The third thing I’d like to just touch on is this idea of practical versus useless. The modern world really values things like practicality, productivity, efficiency, and return on investment. And yet Buddhism is asking us to look at uselessness, at “being” rather than “doing”. Looking at things that go beyond worldly concerns, rather than just following worldly concerns. And again, it’s not about becoming impractical or about being lazy and wasting time, but rather a way of holding practical and beyond practical together.

Because if we’re just going to measure our lives, or indeed measure Buddhism, by what it can do for our worldly life, we’re never really going to get the full benefit out of the path. The path does involve a general reorientation from “doing” — from accomplishing goals — to “being”, so that eventually you come out at a place where you are “doing with being”, rather than doing without that being. And we’ll talk much more about the qualities of being, such as the mindfulness, the intentionality, the purposefulness, the compassion and kindness, and the wisdom. All these things are part of what can mark the way we approach whatever it is that we’re doing. But that’s on top of and beyond the “doing” itself.

Not being impractical about our Dharma practice

Now, some of us may not yet be practical, and for us, I would say that Buddhism certainly doesn’t celebrate being impractical. In fact, the English words “practice” and “practical” both come from a Greek origin — praktikós (πρακτικός)32For etymology of πρακτικός, see wiktionary. — which means “fit for action” or “practical”. It also means “active, effective, vigorous”. And this points to two common faults that we may have [in our Dharma practice]:

- (Over-intellectualization): One is that it’s easy to get stuck in theory. We can argue about what Buddhism says, we can read lots of books, we can impress our friends with our knowledge, but not necessarily put any of it into practice.

- (Lack of energy and effort): And there’s a second way that we can fail to put things into practice, which is through a lack of energy or diligence or effort.

And the path has antidotes [for these faults]. In the Mahayana, we have the practice of the six paramitas33paramita (Pāli & Sanskrit: पारमिता) = perfection, transcendent perfection, transcendental perfection, transcendental virtue. Noble character qualities and virtues generally associated with enlightened beings and cultivated on the Buddhist path. Literally means “reaching the other shore” or “gone to the other shore”. Particularly, it means transcending concepts of subject, object and action. The bodhisattva path comprises the cultivation of six paramitas (generosity, discipline, patience, diligence, meditative concentration, and wisdom) – see paramita.. The fourth of these is virya34virya (Sanskrit: वीर्य) = energy, diligence, enthusiasm – see virya., which is energy or diligence or enthusiasm, and it is all about how can we cultivate this sort of very practical and engaged attitude to our path, which then creates the foundation for going beyond practicality.

Rinpoche has also said many times, “Don’t make yourself a burden on others”. Ever since Jack Kerouac wrote “The Dharma Bums” back in the late 1950s35“The Dharma Bums” is a 1958 novel by Beat Generation author Jack Kerouac. The protagonist’s search for a “Buddhist” context to his experiences (and those of others he encounters) recurs throughout the story. The book had a significant influence on the Hippie counterculture of the 1960s – see wikipedia., the Dharma has always attracted its fair share of hippies and dropouts. Of course, they are welcome. But in the same way that Buddhism is not about attachment to the samsaric, worldly life, it’s also not about attachment to being a dropout.

Embracing uselessness

So what does it mean to go beyond the [practical] concerns of this world? [To go beyond efficiency and economic value creation?] Of course, as Rinpoche often says, even meditation itself is useless. We’re literally “doing” nothing. We’re not accomplishing anything while we’re sitting on our cushion. It’s not productive. Now, I know that of course the contemporary mindfulness movement is trying to [convince] us of the benefits in psychological or business terms. But that’s really something quite different from a Buddhist practice of learning just to be [where questions of cost and benefit do not even enter the conversation].

There’s a lovely Taoist story from the Chuang-Tzu36Chuang-Tzu or Zhuangzi (Chinese: 莊子; pinyin: Zhuāngzǐ, literally “Master Zhuang”) = an influential Chinese Taoist philosopher who lived around the 4th century BCE during the Warring States period. He is regarded as a transmitter and major innovator of the Taoist teachings of Laozi (老子), and also credited as the author of at least part of the work bearing his own name, the Zhuangzi, which is considered as one of the foundational texts of Taoism – see Zhuangzi.. It’s from the first chapter, which is called “Free And Easy Wandering”. Even the chapter title is so beautiful.37The translation below is by Burton Watson from his 1968 book “The Complete Works of Zhuangzi”.

Hui Tzu said to Chuang Tzu, “I have a big tree of the kind men call shu. Its trunk is too gnarled and bumpy to apply a measuring line to, its branches too bent and twisty to match up to a compass or square. You could stand it by the road and no carpenter would look at it twice. Your words, too, are big and useless, and so everyone alike spurns them!”

Chuang Tzu said, “Maybe you’ve never seen a wildcat or a weasel. It crouches down and hides, watching for something to come along. It leaps and races east and west, not hesitating to go high or low — until it falls into the trap and dies in the net. Then again there’s the yak, big as a cloud covering the sky. It certainly knows how to be big, though it doesn’t know how to catch rats.

Now you have this big tree and you’re distressed because it’s useless. Why don’t you plant it in Not Even-Anything Village, or the field of Broad-and-Boundless, relax and do nothing by its side, or lie down for a free and easy sleep under it? Axes will never shorten its life, nothing can ever harm it. If there’s no use for it, how can it come to grief or pain?”

And especially if you practice the highest teachings in the Tibetan tradition, Mahamudra or Mahasandhi, you’ll find this praise of uselessness throughout these teachings. One of my favourite prayers is by HH Dudjom Rinpoche, Rinpoche’s grandfather. His “Calling The Lama From Afar” has a line [which encapsulates the spirit of Dzogchen]38This text is available on the Practice page – see Calling The Lama From Afar.:

“Let this life be spent in this state of uninhibited naked ease.”

So yes, we will see a lot of these ideas of uselessness, of ease, of seemingly just being somebody who doesn’t want to accomplish anything in the world. But that’s not the whole story. We need to go beyond [practicality and usefulness], but at the same time we need to be able to be practical and useful.

Again, just a little about me. In my profession, I’m a business school professor, and I’m an executive coach to some successful people in business, government and society. I say this to reassure you that I understand the world of being practical, even though I’m steeped in the nondual path.

But I’m also very aware of the difficulty of making change in our lives, or following any kind of path or practice. So I hope we’ll have a chance to talk about this also.

I’m going to pause for a break now for 10 minutes. But after the break, I want to come back and talk about the goals of Buddhism. What is the path about? What can we hope to achieve or accomplish? And we will also talk a little bit about you said you’d like out of the path. And if you have a moment for reflection over the next 10 minutes, I would like to invite you just to write this down. Please feel free, if you would like, to write it in the YouTube chat.

REFLECTION

What drew you to Buddhism? What are you hoping to get out of the path? Or indeed, if you’ve come for mindfulness, [what are you hoping to get] out of mindfulness or vipassana, whatever you’re looking for.

And please don’t be shy. I mean, don’t say that you have no hopes. Unless you’ve already achieved a state very close to enlightenment, we are all still functioning in this world of hope and fear. But I would like to invite you to think about it for a moment, because I think this idea of purpose or goal or intention is quite important. So we’ll come back in 10 minutes and talk about that.

[END OF PART 1]

Part 2

Welcome back. And I see that some of you are writing in the chat, so thank you.

Again it is really important to spend time to think about why we do things. That’s true just as much in our ordinary worldly lives as it is in our Dharma practice. I looked across all [that you wrote], not just what you’re saying here, but what you wrote in your registration forms. And I’d say there are three broad themes of things that people are looking for.

(3) What are we seeking in following the Buddhist path?

(a) Outer goals (material)

Lifestyle, behaviours and worldly outcomes

The first is what I would call “outer” things. Things around our lifestyle, our behaviour, the way we show up in the world. The typical kinds of things you see in self-help, positive psychology, leadership, coaching. Things like better relationships at home and work. How to be good with our kids, better parents. How to be more successful in dating, no less. Of course, people are interested in applying Dharma to the workplace. How can they be better leaders? Develop a kinder, more productive, more engaged workplace.

Rinpoche often talks about King Ashoka, the great patron of Buddhism in ancient India. And he has often said that if we really ever expect to have a Buddhist society, we will need our kings and our CEOs to be Buddhists too. So we can’t think of Buddhism as something that doesn’t impact our outer world. And of course, there are a lot of people, especially in the West now, who are very interested in engaged Buddhism. Social justice, climate change, environmental problems, racism, black Buddhism, discrimination of all kinds, LGBTQ, etc.

Of course, the world is in a difficult state externally. And I think a lot of people are asking, “Well, surely Buddhism has some kind of role to play here? What is this role?” So that’s one big topic — the outer world, and how can Buddhism help us live better in the world.

(b) Inner goals (emotional/experiential)

Everyday experiences and emotions – happiness and sadness

The second big area is what I would call the “inner” world. The world of our thoughts, our emotions, our experiences. [Almost all of] us want to be happy. We don’t want to suffer. I saw that Abby wrote on the thread that she has generalized anxiety disorder, and is looking to Buddhism to help alleviate her anxiety. Many people now are suffering from mental health challenges. Anxiety, depression, stress, trauma. Now it’s becoming the biggest health problem in the world.

But there’s also a positive side to experience, and a lot of people are looking for peace, happiness, the sort of experiences we have with beauty, wonder, joy. And we know that the “outer” and the “inner” are of course related, but we also know they’re not that tightly related. We know that money on its own won’t make you happy. As the Beatles sang, “Money can’t buy me love”. Even from work in trauma, we know that the difference between an experience becoming trauma and creating PTSD, versus leading to post-traumatic growth, has less to do with the experience [itself] and more to do with the way we internally make meaning [and construct a narrative for ourselves to make sense of the experience].

I think in general, especially in the West, since the 1960s there has been much more interest in the path of happiness, rather than just the path of outer success. So I think there’s a big area there — in what I would call the ordinary experiences of happiness and sadness.

Extraordinary, peak and mystical experiences

But there’s also another set of experiences which I would call extraordinary experiences. There’s a lot of interest now about peak experiences and flow experiences, [which can manifest] when athletes or performers are in the zone, when the self seems to fall away. Abraham Maslow, the psychologist, wrote about this a lot. Here’s how he described it:

“Feelings of limitless horizons opening up to the vision, the feeling of being simultaneously more powerful and also more helpless than one ever was before, the feeling of great ecstasy and wonder and awe, the loss of placing in time and space with, finally, the conviction that something extremely important and valuable had happened, so that the subject is to some extent transformed and strengthened even in his daily life by such experiences.”39Maslow, Abraham (1970). “Religious aspects of peak-experiences”. In Sadler, W. A. (ed.). Personality and Religion, p. 170.

Another theme we’re seeing a lot of these days is the rise of psychedelics, especially in therapeutic applications for PTSD, etc. And it seems to be [case] that they are quite remarkable [in their effectiveness], far more so than antidepressants. If any of you have haven’t come across Michael Pollan’s lovely book, “How To Change Your Mind”, I recommend it to you. He’s not at all a Buddhist. He’s very skeptical himself. But he ends up with quite a Buddhist view, after having tried all manner of psychedelics and experienced the effects for himself. And he says:

“This sense of merging into some larger totality is of course one of the hallmarks of the mystical experience; our sense of individuality and separateness hinges on a bounded self and a clear demarcation between subject and object. But all that may be a mental construction, a kind of illusion — just as the Buddhists have been trying to tell us. The psychedelic experience of “non-duality” suggests that consciousness survives the disappearance of the self, that it is not so indispensable as we — and it — like to think.”40Pollan, Michael (2018) How To Change Your Mind.

Personally, I love the fact that somebody who comes in as skeptical as him, who is not a Buddhist, can nevertheless come to that conclusion. Because there is this whole question of spiritual experience. Even in the modern world where many of us no longer wish to partake of religion, a lot of us would identify as “spiritual but not religious”. So there’s this idea that, yes, there are still these experiences. There’s some sense of spiritual awe, there’s some sense of something bigger.

Addicted customers = profitable customers

And I do think, by the way, as we now start technology giving us immersive virtual reality, I think we’re going to start to see not just psychedelics, but a lot of technologically induced states. And if we’re not careful, I think we’ll find that the big tech companies will start to have more and more control over our experience41The Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari has written eloquently on this topic in his 2018 book “21 Lessons for the 21st Century”. For example in Ch. 4 “Equality”:

“At present, people are happy to give away their most valuable asset – their personal data – in exchange for free email services and funny cat videos. It is a bit like African and Native American tribes who unwittingly sold entire countries to European imperialists in exchange for colourful beads and cheap trinkets [. . . ] As more and more data flows from your body and brain to the smart machines via the biometric sensors, it will become easy for corporations and government agencies to know you, manipulate you, and make decisions on your behalf.”

Harari is also a Vipassana practitioner and student of S.N Goenka. I strongly recommend him as a contemporary public intellectual and big-picture thinker who brings a Buddhist perspective to his analysis of the modern world. See the interviews in GQ and New Yorker, his official website, and also wikipedia.. And if we don’t find a way to manage our side of that, I think it could become a little bit like the way we’ve become so vulnerable in the face of the food industry, where they’ve found the way to “engineer” the sweet spot [which is called the “bliss point”42The bliss point is the amount of an ingredient such as salt, sugar or fat which optimizes deliciousness (in the formulation of food products) – see wikipedia.] of sweet and salty and fatty, just so that we [become addicted and keep] buying cheap junk food43See, for example, the 2013 book by Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist Michael Moss “Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us”, and also the three-part 2012 BBC documentary series “The Men Who Made Us Fat” by Jaques Peretti, available on BBC Two.. And what have we seen? We’ve seen a worldwide explosion in obesity.

And a lot of people are now concerned about how our world of advertising, our world of social media, the Internet in general [is also working to hijack our attention]. There are so many psychology PhDs in Silicon Valley whose work is about how to get you addicted to their apps or their websites. There’s a wonderful book called “Hooked” by Nir Eyal, who was one of these “behavioural engineers” himself, where he explains how to get people addicted [literally to “build products that create habit-forming behaviour in users”44See the entry on Nir Eyal in wikipedia.]. And then he [subsequently] wrote another book “Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life”, where you can sense that he is perhaps trying to make amends for [what] he wrote in his first book.45Ed.: but perhaps only to a certain extent. He has spoken out against proposals to regulate habit-forming technologies, arguing that “it is an individual user’s responsibility to control their own use of such products” – see wikipedia.

But, the reality is that going forwards, we are going to be in a world where the capitalist system is doing its best to get us addicted to products and services. And [businesses are] finding better and better ways of doing this, and now our minds and our emotions are fair prey. So if we don’t find a way of learning to achieve some mastery of our inner world, I think we’re going to be quite vulnerable.

Living a good life: ethics, purpose, meaning

There’s another set of concerns, which are about ethics. How to live a good life? Many of you wrote about purpose — how to be a good person, how to be a kind person, how to be authentic, how to live according to values? And what does it mean to have secular or humanistic ethics in a post-religious world? And again, what does Buddhism have to say about these topics? What does Buddhist ethics actually mean?

Another big question is purpose. Life design. Identity. What should I do with my life? Is there a Buddhist perspective on that? We kind of know that consumerism is not the way. Most of us realize that materialism has its limits. And there’s been a big rise in minimalism, decluttering, focusing, Zen, mindfulness — all these ideas that life has become too complicated, too busy, too much stuff. So what, if anything, does Buddhism have to offer us there?

Finally, in this domain of the inner world, and also with purpose. Rinpoche is also talking about this now. As artificial intelligence comes, and we have this coming identity crisis, and the machines take our jobs. Who are we then? So many of us are so identified with our work, that when we no longer have work in the ordinary sense, how will we make sense of our lives. And Rinpoche says, and I agree, the need will become stronger than ever to find a way of making sense of who we are — as people, as humans, as a society — that doesn’t just refer back to the conventional ways of thinking about meaning. I think Buddhism has an awful lot to offer here. So that’s the second [category], the “inner”.

(c) Innermost goals

The wisdom of self-awareness

The third is the innermost, which is the domain of awareness or wisdom. We’ve often had the idea, a sense there’s more to life than this. There’s something else going on behind appearances. And most famously, in the in the scene in “The Matrix” with the red pill and the blue pill. Do we really want to wake up to what reality is really about? So we hear words like wisdom, self awareness, recognizing our true nature.

And this has also been a concern of Western philosophy and of course, Eastern wisdom traditions since the very beginning. The Temple of Apollo at Delphi, which dates back to the 4th century BCE, was famous for the quote “Know thyself”46Know thyself (Greek: γνῶθι σεαυτόν, transliterated: gnōthi seauton) – see wikipedia. inscribed in the forecourt of the temple. [The wisdom of self-knowledge] has always been an aim of Western philosophy. What does it mean to live authentically? To answer the question, we have to know who we really are. Because authenticity is about being true to who you really are. And if you don’t know that, how can you be authentic?

Awareness without a self

Now, Buddhism, of course, goes a little further, a little deeper. It talks about the nature of phenomena, the nature of mind. And all this then leads to conversations about awakening, liberation, freedom, enlightenment,. These are big, big words. We’ll talk about this over the coming weeks as well. But I would say that just in the same way that the inner world is more — and indeed a different dimension — than the outer world. And the innermost world is actually more — and different — from the inner world also. Because if we’re able to shift our awareness, to shift our way of being, it changes our relationship to all our thoughts, our emotions, our self.

Going back to that Michael Pollan quote, where he says, “The psychedelic experience of nonduality suggests that consciousness survives the disappearance of the self.” So what is this? It’s clearly beyond the domain of the inner world of psychology, because psychology is still about self. What happens when you have no self, when you just have awareness? What is that? So yes, we’ll talk a lot about that too.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

And of course, you can compare this to the Western psychological tradition. [The idea of different kinds of aspirations was] most famously expressed in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, where at the outer level, you have material needs, basic needs of food and water and safety. Then at the inner level, you have psychological needs. How to be happy? How to build friendships and intimate relationships? How to build a purposeful life? Then there’s self-fulfillment, how to achieve one’s full potential, how to live authentically. He called this “self-actualization”.

But it was only much later in his life that he came to accept the idea of [something above self-actualization that is] “beyond worldly”. He called it “self-transcendence”. He talked in terms of:

“The transcendence of identity … the Eastern [goal] of ego-transcendence and obliteration, of leaving behind self-consciousness and self-observation”

He also said that:

“It looks as if the best path to this goal for most people is via achieving identity, a strong real [conventional] self, and via basic-need-gratification.”

I’m not sure that a Buddhist perspective would agree with that, and we can certainly talk about that. But just to say that these three — the outer, the inner, the innermost — the worldly, the psychological, and the world of wisdom and awareness — these are part of the human condition. These have been timeless, there for thousands and thousands of years. They cut across all cultures, and all human eras.

What if we are only interested in worldly happiness and success?

You might ask, “Well, what if my only aspirations are just for worldly happiness and success? Can I still be a Buddhist?” Of course. Buddhism is never going to begrudge you the use of the path for whatever purposes you wish. And a lot of the Western interest — the contemporary interest in mindfulness, compassion, self compassion — this is very much why we’re using [these techniques].

We’re applying them in some cases for outer [purposes]. When we talk about mindful parenting, we talk about mindful leadership. And of course, inner things. There’s so much mindfulness in psychology and therapy. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy is one of the most effective evidence-based therapies now. So yes, it’s really helping people. And yet, there is more.

I wouldn’t want you to stop just there. As Rinpoche says, it’s a bit like using gold leaf to wipe your bottom. Or perhaps in a slightly less dramatic example, you could say it’s a bit like using your $5,000 laptop as a doorstop. Yes, it functions for that purpose. But you’re not using all that it can be. And it would be a sham if you were to learn about Buddhism, engage in the Buddhist path, and [yet] never give yourself the chance to find out what its real intention is.

So yes, Buddhism is in no way against you being successful, it’s in no way against you being happy. Far from it. Although, it would question if you put your quest for success above your spiritual path. Or indeed, if you put your quest for happiness above your spiritual path. Rinpoche’s second book was called “Not For Happiness”. And his point is very clear. It’s not that we don’t want happiness. Of course we do. But if that’s the only thing you look to Buddhism to give you, you’re missing something.

Actually, this is one of these sort of paradoxes, because all of these [outcomes] are welcome. I was noticing that even when His Holiness The Dalai Lama talks about Buddhism, he gives all three of these:

- (Outer): He talks about the outer world. He says, “My religion is very simple. My religion is kindness.” How can I just live in the world in a way that’s kind?

- (Inner): He also talks about the inner world. He says, “I believe that the purpose of life is to be happy. From the moment of birth, every human being wants happiness and does not want suffering. Neither social conditioning nor education nor ideology affect this.”

- (Innermost): But then he also says, “In all the orders of Tibetan Buddhism … their systems come down to the same final principle [. . . ] called “ordinary consciousness” and “innermost awareness [. . . ] [which is] the basis of the appearance of all of the round of suffering and also the basis of liberation (called “nirvana”)47 And: “Although it is difficult to pinpoint the physical base or location of awareness, it is perhaps the most precious thing concealed within our brains.”

So just to say, all of those things are really [included in what we might aspire for]. And if all of that seems perhaps a little much, here’s a very everyday example. This is the singer Billy Eilish, one of the heroines of Gen Z. There was a nice article with an interview with her in The Guardian a few days ago. She said:

“Since I was a kid, my dad and I have always talked about a certain type of person who’s so insecure, or hyperaware and self-conscious, that they never move in a weird way, or make a weird face, because they always want to look good. I’ve noticed that, and it makes me so sad. If you’re always standing a certain way, walking in a certain way, and always have your hair just so [. . . ] It’s such a loss to always try to always look good. It’s such a loss of joy and freedom [. . .]”47“Billie Eilish: ‘To always try to look good is such a loss of joy and freedom’”, Miranda Sawyer, The Guardian. July 31, 2021.

I think it’s worth reflecting on that. Maybe for us, we’re not concerned about having our hair just so. Or maybe we are. So:

REFLECTION

What are all of the ways that we are not free, because of our own need to look good, or to be liked, or to fit into social conventions?

So [perhaps we can become more aware of how] actually, we all get caught up playing this worldly game, and so much of the time we don’t even notice it. So yes, of course, we should aspire for enlightenment. But I think it can be good to start by just looking at some of the very basic ways that we are not free in our day to day lives.

(d) Aspiration as a practice

Training in aspiration is a practice

And in Buddhism, the idea of motivation or aspiration is a practice, given the importance of choosing the right goal. Of course, taking refuge is for all Buddhists, the most foundational way that you define yourself to be a Buddhist. In the Mahayana, it becomes about bodhichitta and the bodhisattva vow. And for Mahayana Buddhists in particular, our aspiration is no longer just about what Buddhism can do for us, but about [awakening] all beings. Partly because in the Mahayana, even the idea of self is seen as a cognitive distortion. It’s a mistake. It may seem far beyond us today, to understand what that might mean. But that’s why it’s a practice.